Читать книгу The Other Woman - Daniel Silva - Страница 20

11 ANDALUSIA, SPAIN

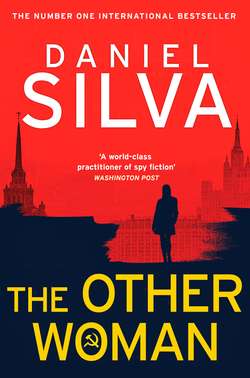

ОглавлениеThe villa clung to the edge of a great crag in the hills of Andalusia. The precariousness of its perch appealed to the woman; it seemed it might lose its grip on the rock at any moment and fall away. There were nights, awake in bed, when she imagined herself tumbling into the abyss, with her keepsakes and her books and her cats swirling about her in a ragged tornado of memory. She wondered how long she might lie dead on the valley floor, entombed in the debris of her solitary existence, before anyone noticed. Would the authorities give her a decent burial? Would they notify her child? She had left a few carefully concealed clues concerning the child’s identity in her personal effects, and in the beginnings of a memoir. Thus far, she had managed only eleven pages, handwritten in pencil, each page marked by the brown ring of her coffee mug. She had a title, though, which she regarded as a notable achievement, as titles were always so difficult. She called it The Other Woman.

The scant eleven pages, the sum total of her labors, she regarded less charitably, for her days were nothing if not a vast empty quarter of time. What’s more, she was a journalist, at least she had masqueraded as one in her youth. Perhaps it was the topic that blocked her path forward. Writing about the lives of others— the dictator, the freedom fighter, the man who sells olives and spice in the souk—had for her been a relatively straightforward process. The subject spoke, his words were weighed against the available facts—yes, his words, because in those days women were of no consequence—and a few hundred words would spill onto the page, hopefully with enough flair and insight as to warrant a small payment from a faraway editor in London or Paris or New York. But writing about oneself, well, that was an altogether different matter. It was like attempting to recall the details of an auto accident on a darkened road. She’d had one once, with him, in the mountains near Beirut. He’d been drunk, as usual, and abusive, which was not like him. She supposed he had a right to be angry; she had finally worked up the nerve to tell him about the baby. Even now, she wondered whether he had been trying to kill her. He’d killed a good many others. Hundreds, in fact. She knew that now. But not then.

She worked, or pretended to work, in the mornings, in the shadowed alcove beneath the stairs. She had been sleeping less and rising earlier. She supposed it was yet another unwelcome consequence of growing old. On that morning she was more prolific than usual, an entire page of polished prose with scarcely a correction or revision. Still, she had yet to complete the first chapter. Or would she call it a prologue? She’d always been dubious about prologues; she regarded them as cheap devices wielded by lesser writers. In her case, however, a prologue was justified, for she was starting her story not at the beginning but in the middle, a stifling afternoon in August 1974 when a certain Comrade Lavrov—it was a pseudonym—brought her a letter from Moscow. It bore neither the name of the sender nor the date it was composed. Even so, she knew it was from him, the English journalist she had known in Beirut. The prose betrayed him.

It was half past eleven in the morning when she set down her pencil. She knew this because the tinny alarm on her Seiko wristwatch reminded her to take her next pill. It was her heart that ailed her. She swallowed the bitter little tablet with the cold dregs of her coffee and locked the manuscript—it was a pretentious word, admittedly, but she could think of no other—in the antique Victorian strongbox beneath her writing table. The next item on her busy daily schedule, her ritual bath, consumed all of forty minutes, followed by another half hour of careful grooming and dressing, after which she left the villa and set out through the fierce early-afternoon glare toward the center of the village.

The town was white as dried bone, famously white, and balanced atop the highest point of the incisor-like crag. One hundred and fourteen normal paces along the paseo brought her to the new hotel, and another two hundred and twenty-eight steps carried her across a patch of olive and scrub oak to the edge of the centre ville, which was how, privately, she referred to it, even now, even after all her years of splendid exile. It was a game she had played with her child long ago in Paris, the counting of steps. How many steps to cross the courtyard to the street? How many steps to span the Pont de la Concorde? How many steps until a child of ten disappeared from her mother’s sight? The answer was twenty-nine.

A graffiti artist had defiled the first sugar-cube dwelling with a Spanish-language obscenity. She thought his work rather decent, a hint of color, like a throw pillow, to break the monotony of white. She wound her way higher through the town to the Calle San Juan. The shopkeepers watched her disdainfully as she passed. They had many names for her, none flattering. They called her la loca, the crazy one, or la roja, a reference to the color of her politics, which she’d made no attempt to hide, contrary to the instructions of Comrade Lavrov. In fact, there were few shops in the village where she had not had an altercation of some sort, always over money. She regarded the shopkeepers as vulture capitalists, and they thought her, justifiably, a communist and a troublemaker, and an imported one at that.

The café where she preferred to take her midday meal was in a square near the town’s summit. There was a hexagonal islet with a handsome lamp at its center and on the eastern flank a church, ocher instead of white, another respite from the sameness. The café itself was a no-nonsense affair—plastic tables and chairs, plastic tablecloths of a peculiarly Scottish pattern—but three lovely orange trees, heavy with fruit, shaded the terrace. The waiter was a friendly young Moroccan from some godforsaken hamlet in the Rif Mountains. For all she knew, he was an ISIS fanatic who was plotting to slit her throat at the earliest opportunity, but he was one of the few people in the town who treated her kindly. They addressed one another in Arabic, she in the stilted classical Arabic she had learned in Beirut, he in the Maghrebi dialect of North Africa. He was generous with the ham and the sherry, despite the fact he disapproved of both.

“Did you see the news from Palestine today?” He placed a tortilla española before her. “The Zionists have closed the Temple Mount.”

“Outrageous. If the fools don’t open it soon, it will be the ruin of them.”

“Inshallah.”

“Yes,” she agreed as she sipped a pale Manzanilla. “Inshallah, indeed.”

Over coffee she scratched a few lines into her Moleskine notebook, memories of that August afternoon so long ago in Paris, impressions. Diligently, she tried to segregate what she knew then from what she knew now, to place herself, and the reader, in the moment, without the bias of time. When the bill appeared, she left twice the requested amount and went into the square. For some reason the church beckoned. She climbed its steps—there were four—and heaved on the studded wooden door. Cool air rushed out at her like an exhalation of breath. Instinctively, she stretched a hand toward the font and dipped the tips of her fingers into the holy water, but stopped before performing the ritual self-blessing. Surely, she thought, the earth would tremble and the curtain in the temple would tear itself in two.

The nave was in semidarkness and deserted. She took a few hesitant steps up the center aisle and inhaled the familiar scents of incense and candle smoke and beeswax. She’d always loved the smell of churches but thought the rest of it was for the birds. As usual, God on his Roman instrument of execution did not speak to her or stir her to rapture, but a statue of the Madonna and Child, hovering above a stand of votive candles, moved her quite unexpectedly to tears.

She shoved a few coins through the slot of the box and stumbled into the sunlight. It had turned cold without warning, the way it did in the mountains of Andalusia in winter. She hurried toward the base of the town, counting her steps, wondering why at her age it was harder to walk downhill than up. The little El Castillo supermarket had awakened from its siesta. From the orderly shelves she plucked a few items for her supper and carried them in a plastic sack across the wasteland of oak and olive, past the new hotel, and finally into the prison of her villa.

The cold followed her inside like a stray animal. She lit a fire in the grate and poured herself a whisky to take the chill out of her bones. The savor of smoke and charred wood made her think, involuntarily, of him. His kisses always tasted of whisky.

She carried the glass to her alcove beneath the stairs. Above the writing desk, books lined a single shelf. Her eyes moved left to right across the cracked and faded spines. Knightley, Seale, Boyle, Wright, Brown, Modin, Macintyre, Beeston … There was also a paperback edition of his dishonest memoir. Her name appeared in none of the volumes. She was his best-kept secret. No, she thought suddenly, his second best.

She opened the Victorian strongbox and removed a leatherbound scrapbook, so old it smelled only of dust. Inside, carefully pasted to its pages, was the meager ration of photographs, clippings, and letters Comrade Lavrov had allowed her to take from her old apartment in Paris—and a few more she had managed to keep without his knowledge. She had only eight yellowed snapshots of her child, the last one taken, clandestinely, on Jesus Lane in Cambridge. There were many more of him. The long boozy lunches at the St. Georges and the Normandie, the picnics in the hills, the drunken afternoons in the bathing hut at Khalde Beach. And then there were the photos she had taken in the privacy of her apartment when his defenses were down. They had never met in his large flat on the rue Kantari, only in hers. Somehow, Eleanor had never found them out. She supposed deception came naturally to them both. And to their offspring.

She returned the scrapbook to the Victorian strongbox and in the sitting room switched on her outmoded television. The evening news had just begun on La 1. After several minutes of the usual fare—a labor strike, a football riot, more unrest in neighboring Catalonia—there was a story about the assassination of a Russian agent in Vienna, and about the Israeli spymaster alleged to be responsible. She hated the Israeli, if for no other reason than the fact he existed, but at that moment she actually felt a bit sorry for him. The poor fool, she thought. He had no idea what he was up against.