Читать книгу A Geek in Korea - Daniel Tudor - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE RISE OF COOL KOREA

“Korea? But there’s a war going on there, isn’t there?”

“Korea? Do you mean the North, or the South?”

These were the kind of reactions I got when I first told people I was going to live in Korea. They knew about the Korean War; they knew about the dictator in Pyongyang so memorably rendered in Team America: World Police; and, they also “knew” that dog-eating was a “common practice;” “Remember, Danny: a dog is for life, not just Christmas dinner,” wrote one old friend in a card sent to me for the 2004 holiday season.

But something has changed. In the past decade or so, Korea—and by “Korea,” I am referring to the South—has become cool. Though still off the radar for many Westerners, inbound tourist numbers have rocketed; creative exports like computer games, pop music, movies, and even the odd novel, have gained international attention in a way that no one here would have dared imagine at the turn of the millennium.

Around Asia, Korean “idol” stars are greeted with Beatlemania-style levels of hysteria. Actors like Bae Yong-joon are worshipped by legions of Japanese housewives. And a critical blog post about a top Korean pop group’s latest single will draw from overseas fans the kind of wrath that I would reserve for someone who had just gravely insulted my mother.

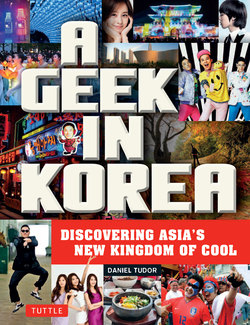

The new face of Korea? There are few people in the world who don’t recognize Psy, of “Gangnam Style” fame. His charmingly silly image has provided a great counterpoint to traditional conceptions of Korea, which center on the Korean War and industrial development.

In the days of its rapid development, Korea inevitably had a rather gray, industrial image. Celebrities are now adding color, but this is only half the story. Today, a student toting a heavy bag full of textbooks might also have a guitar slung over his shoulder. Particularly around the Hongik University area of Seoul, there has been a flowering of “indie” culture. The bars and cafes there are full of people whose dreams are of rock n’ roll, rather than of working for Samsung. They are driving “cool Korea” just as much as any actor with fancy hair.

But even if the Korean hipster isn’t sure about becoming “Samsung Man,” there’s still a good chance Samsung will have made the phone in his pocket. Korean firms are now overtaking Japanese rivals and dominating markets worldwide in all types of funky gadgets. Hyundai cars used to be something of a joke in the US, but now they win awards. And in defiance of the risk aversion of their parents’ generation, a new breed of high-tech start-up entrepreneur is emerging.

But why is all this happening? Is it just a matter of coincidence that Koreans suddenly seem to be making internationally successful music and movies, as well as the mp3 players and flat-screen TVs on which we appreciate them? Is it the result of a new focus on style and quality now the develop-at-all-costs philosophy of the past half century is finally subsiding? Is it the result of the political democratization of the past 25 years? Or is it, as cultural commentator and TV presenter Park Jung-sook says, simply Korea’s turn to shine?

My cop-out answer is all of the above. But it is a pleasure to watch it all unfold, and a privilege to be able to write about it. I will consider this book a job well done if I can convince you to come here and see it all for yourself. So, I hope to see you in Seoul!

Falling in Love with a Country

There are many reasons why people come to this country. Some come for work, others come for marriage, and there are even those who are so obsessed with a particular Korean TV star or pop group that they pack up their things and move to Seoul. These days, there are also a few who have noticed “cool Korea” and want to get in on it. But for me, it all started with a sporting event.

I first set foot in Korea on the day the national football team played Italy in the 2002 World Cup. We’d been on the move for well over fifteen hours, in a journey that took in two plane rides and a bumpy trek in a car up the coast from Busan to the industrial city of Ulsan. Shattered, we stood at the check-in desk, waiting for service. The staff had no interest in helping us. They were watching TV: the match had gone to extra time, and it was made clear that everything had to wait until that deciding golden goal sailed beyond the outstretched hands of an agonized goalkeeper. When it did—courtesy of Korea’s famed pretty-boy striker Ahn Jung-hwan—the joy that erupted was of the like of which I had never seen before. In the lobby of our five-star hotel, people dressed in red t-shirts, red bandanas, and with red face paint on, were bouncing in every direction. (continued on next page)

They crashed into each other, into us, and into pillars. They scattered chairs, and whatever hotel furniture dared stand in their way. They screamed and hugged with abandon. Despite being tired (and British), we became swept up in the tide of emotion. So we drank, danced, and yelled along with these overjoyed Korean fans for the rest of the day. We’d never seen them before, and would never see them again. The language barrier meant we couldn’t even communicate properly. But for that one day, it felt like we’d known them all our lives.

It was like that for the rest of the tournament. We’d wander around Seoul carrying a ball, and strangers would challenge us to a game in the street. We’d then proceed to get drunk on soju (an alcoholic spirit) with them afterwards. It was a time of overwhelming humanity: everyone was your friend, and there were no barriers between people. Entire offices packed up and went out into the streets. Bar owners would say, “here, have some more drinks on the house!” Normal rules were completely suspended, but nobody did you any harm.

I knew that the “World Cup spirit” couldn’t last forever. But I also knew that there must have been something special about a country that could produce such an atmosphere. So I made up my mind to return. Now I work here, Korea has become “normal” to me—but the occasional burst of dynamic devil-may-care fun or act of great kindness from a stranger reminds me of why I first came to like this place so much.

I am also lucky to have built some extraordinary friendships here. Korea is certainly not a country without problems—many of which are covered in this book—but at the heart of its culture lies a redeeming warmth and humanity that is hard to find anywhere else.

KOREA: IT’S DIFFERENT

Every time I walk past a street vendor selling silkworm larvae as a snack, I’m reminded that “Korea is different.” But it isn’t just different in that “exotic” or “eastern” kind of way. Certainly, Korea has plenty in common with its neighbors, as can be expected; but those who think Korea is “just like China” or “just like Japan” are badly mistaken.

The main reason why Korean TV drama series are popular around Asia is that they are full of raw emotion. Unlike in Japan, where self-control is a social necessity, Koreans can be refreshingly direct with how they feel towards you. Whether those feelings are of love, anger, or indifference, you won’t need to scratch your head wondering which. Due to a tendency for passionate and expressive behavior, Koreans are sometimes compared (and sometimes compare themselves) to the Italians.

Another stereotype with some degree of truth is that of Koreans as “the Irish of the East.” This is not just due to the statistical fact that Koreans are by far the biggest drinkers in East Asia. For centuries, Koreans have been known as lovers of singing and dancing. Collectively, the Korean culture of drinking, singing, and dancing is known as eumjugamu. The word has negative connotations to some Koreans, but for me, it is one of the most attractive and defining aspects of Korean culture.

There also exists what I call a “natural socialism” in Korean culture. Even when individual portions are served in a restaurant, friends will move their plates into the center of the table, and share everything. “Every man for himself”—as found in today’s China—is not a popular concept in Korea. Social inequality, though increasing, is considered a problem to be tackled rather than an inevitability to be accepted; even Korea’s most conservative politicians feel compelled to confront this.

Korea is also a land of sad extremes. Proportionally, this country is world number one in terms of suicide, plastic surgery, and expenditure on “bling bling” luxury goods. It also has probably the world’s most stressed-out, over-burdened schoolchildren. All these are results of Korea’s intense culture of competition, which makes it unacceptable to be merely good-looking, well-off, and well-educated. One must compete with others to be the best-looking, best-off, and best-educated.

It sounds like a total contradiction to say that Koreans are natural socialists who love drinking and partying, and yet are engaged in a vicious cycle of be-all-you-can-be competition against each other. But it isn’t wrong. Korea is a complicated place of joy and tragedy, of fulfilment and frustration. You can at least be certain that it will never bore you.

My Life in Korea

When I first moved to Seoul, I taught English. Since then, I’ve been an investment manager, and a journalist at The Economist. These days, I’m an independent writer, and co-owner of The Booth, a craft beer business. The gentleman with me in the picture above is Kim Chang-wan, leader of Sanullim, one of Korea’s best-loved rock bands. One of the best aspects of being a bar-owner is the ability to meet interesting people from all walks of life!

Gwanghwamun The gate of Gwanghwamun in front of Gyeongbok Palace in Seoul is the focal point of the country. The nation’s gi (energy) is said to flow through it.