Читать книгу In the Greene & Greene Style - Darrell Peart - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

In my first book, Greene & Greene: Design Elements for the Workshop, I introduced my readers to the world of Greene & Greene. As a woodworker, one of my goals was to find out more about the craftsmen behind the Greene’s work: Peter and John Hall. In that regard, I am forever grateful to the Hall family—especially to Gary Hall (grandson of Peter Hall)—for opening up their homes and sharing their family history with me. Many of the things they showed me were significant to the history of Greene & Greene and had not been previously seen outside the Hall family. I had the honor of filling in a few small blanks in the history of Greene & Greene.

It was the relationship of the two sets of brothers, the Greenes and the Halls, that I was really interested in. Much of this can only be speculation at this point, but the quality of work speaks loudly that that relationship was something divine. Over the years I have worked at many custom woodworking shops and it’s been my experience that when relations between designer/engineer/architect are less than optimal, the final product suffers. On the other hand, when the reverse is true, the work benefits greatly, as it more than did with the collaboration of the Greenes and the Halls.

The style of Greene & Greene was also of prime importance in my previous book. I covered many of the more basic elements (and how to build them) and discussed their importance to the overall design. But there is more to a design than its individual components. Where did the various influences come from and how were they assimilated into the style at large? I think we can comfortably say that Charles Greene was the primary creative force, but I can’t help speculating on what may have been John Hall’s contribution. As is evident by his surviving personal work, John had a well-developed sense of design and was known to work closely with Charles. In any event, the creation of a new style inevitably means uniting previously unrelated elements to a work as a unified whole. In the case of Greene & Greene this never ceased for as long as they were actively designing—new ideas and elements were unceasingly being assimilated.

I ended my last book with a plea to my readers to take what I had presented and “strike out on your own.” I offered up the interpretative Greene & Greene work of three furniture makers (including myself) as examples. Each of these furniture makers had developed their own perspective and had introduced elements of their own to the style.

I have been studying the work of Greene & Greene for many years now. What stands out the most to me is the incredible level of thought behind the almost infinite number of details that became a part of the style. A new detail was never simply created, then cut and pasted here and there when needed. Each use of an individual element was given careful consideration before its use and was quite often “tweaked” to fit the given context. Because of this, Greene & Greene was never static—it perpetually renewed itself—it was in essence alive.

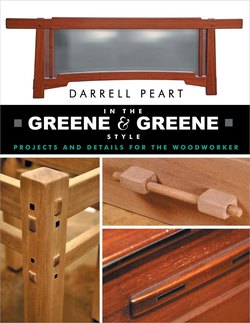

Detail of chest, Chapter 6.

Although there is much educational value in exactly replicating the work of Greene & Greene, truly emulating them on the other hand is something different. For every new design the Greenes took a fresh look. They did not discard the old, but did not precisely repeat it either. Every new design had a life of its own, as if it were a new birth and possessed the family DNA. Each new life introduced new traits to the family gene pool.

With this new book I endeavor to emulate Greene & Greene. I want to encourage my readers to introduce their own decorative elements and to make new use of old elements; to keep the style alive.

Most of the details discussed in this new volume are original to the Greene’s vocabulary, but I have also included ones that have spawned from my drawing board (computer screen), such as the strap detail and the block and dowel pull. Both of these features have made their way into the greater world of G&G woodworking. Of the two, the strap has an original G&G pedigree, while the block and dowel pull is something I borrowed from the work of James Krenov. I feel it is a great compliment to my work when they are used in other woodworkers’ projects and mistaken as details original to the style.

Style is not the only thing that needs to be kept alive and ever changing—methods of works do as well. How I do things at this moment is the best way I know at this time, but sometimes there are many ways to accomplish the same thing and each has its merits, and the best way is then relative to circumstances or just my mood at the time. For this reason I have included alternate approaches for a couple of things from my previous book.

In my last book, because I took up considerable space in introducing Greene & Greene, I did not have room for any projects. In this book I have included projects of my own Greene & Greene style design. Projects are a good way to practice some of the skills discussed in both books. Projects are also good in that they focus the attention on a specific design and in so doing assist in developing a greater knowledge and understanding of what makes that design work.

Again, I would like to encourage my readers to take as little or as much from what I have to offer as suits their fancy. Staying within well-defined boundaries is where all good creative endeavors start. Being different for the purpose of being different is not what I am promoting. Let the desire to branch out develop naturally. When, and if, the urge to deviate pays you a visit, don’t hesitate—go for it!