Читать книгу A Brief Time in Heaven - Darryl Blazino - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

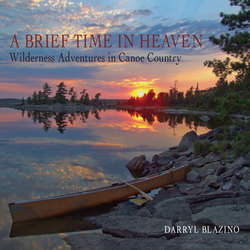

HEAVEN ON EARTH

ОглавлениеAs with many of the world’s greatest parks, Quetico Provincial Park and its sister park, the Boundary Waters Canoe Area, are situated on the edge of transitional ecological zones. Perhaps the park’s most stunning and signature features are its old growth forests of red and white pine that envelop many of the shorelines of the four hundred–plus lakes contained within its borders. For this reason the park is classified as being in the Great Lakes/St. Lawrence forest ecosystem. It lies adjacent to the southern border of the enormous boreal forest region of Canada and not far from the grasslands and great prairies of the North American Plains.

It is also near the headwaters of three main water basins. Just a few miles to the south is the start of the Mississippi River system, while the lakes and streams just east of the park head towards mighty Lake Superior, over Niagara Falls, and eventually to the Atlantic Ocean. The waters within the park itself move west and then north before finally emptying into Hudson Bay and the Arctic Ocean.

I have had the good fortune to visit some of the most incredible places on this earth, including the Great Barrier Reef, the islands of Hawaii, the Grand Canyon, Yosemite, Banff, and Glacier National Parks, and as breathtaking as they are, I still find myself inexorably biased towards Quetico.

Quetico does not completely overwhelm you with the world’s largest trees, highest mountains, deepest gorges, or unique geological anomalies. Rather, it is a place of intimate beauty where, if you take the time to look, listen, and feel, wonder will be revealed to you in other ways. Rarely will the park immediately wow you, but it is as beautiful as anything on this planet. As my friend Rod MacKenzie likes to point out after a spell of rough weather or a difficult portage, the price of admission can be high but you are always repaid in abundance.

Dawn at Russell Lake.

In the summer of 2011 our family undertook the classic American road trip, crossing the Great Plains and Black Hills before spending an incredible week in Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks. Just days later, the boys and I were off to Quetico with the grandeur of Old Faithful and the Yellowstone Falls still vivid in our memories.

The lakes, rivers, cliffs, and trees seemed noticeably smaller to me, and for a moment I wondered if my view of the park would forever be tarnished, albeit ever so slightly. It was a thought that troubled me for that first day — would the beauty of the lake country now always seem second best? Lying in the tent that night after the boys had fallen asleep I restlessly pondered this question. At that moment a commotion erupted across the small lake that was our home on this day.

A pair of loons began flapping repeatedly and filled the hillsides with their hauntingly beautiful cries. I listened in wonderment for a while and then hopped out of the tent and made my way to a large exposed bedrock just above the shoreline. The sun had already set, but the northern sky was still ablaze with a kaleidoscope of orange, purple, pink, and red. A partial moon was glowing bright and sent a sparkling reflection off the water, capturing the distant pines and the dancing loons in silhouette. No one else was there, just me on that rocky ledge with the loons, the moon, and the dazzling twilight, yet a part of me felt the urge to turn to someone beside me and say, “Isn’t that incredible?”

This was why I had come — not specifically for the loons or the sunset, but for the profound and intimate sense of wonderment that always seems to blossom in the north woods. This is not a place where you simply drive up, see a site, and move on; it is one where a magical event is often waiting for you (and sometimes you alone) at any given time in any given place.

Motorized travel within Quetico and the BWCA (with a few exceptions) is forbidden. This vast area, as with much of Northern Ontario, is made for canoeing. To me, canoeing is by far the most incredible form of transportation. So often I am able to enter a mental state where I am completely absorbed by the elements and movement is effortless.

Everything that is needed for a week or more is contained within the craft, and the entire outfit glides silently through open vistas in any direction I choose. At lake’s end this amazing vessel is easily flipped up on my shoulders and we are off through the forest towards the next patch of blue.

One of Canada’s greatest prime ministers, Pierre Elliot Trudeau, described it beautifully: “What sets a canoeing expedition apart is that it purifies you more rapidly and inescapably than any other. Travel a thousand miles by train and you are a brute; pedal five hundred on a bicycle and you remain basically a bourgeois; paddle a hundred in a canoe and you are already a child of nature.”

He also wrote, “Canoeing gets you back to nature, using a method of travel that does not even call for roads or paths. You are following nature’s roads.…You discover a sort of simplifying of your values, a distinction between those artificially created and those that are necessary to your spiritual and human development.”

I often wake before my companions and paddle the shoreline of the early dawn. I find it euphoric, a heavenly experience, a combination of sheer excitement and complete peace. There is no other time in my life when these two incredible yet diametrically opposed feelings coexist.

Rod MacKenzie and George Danio entering Hamburg Lake.

What is it about canoe country that makes it so special? Accessibility to your own small piece of heaven is part of it. The nearly four hundred island-studded lakes in close proximity are interconnected by rivers, streams, and ancient paths called portages. The perimeter of these lakes is often lined with mature red and white pine. Their stunning beauty is only surpassed by their ability to create the most magnificent campsites on this planet. As the lower branches drop their needles a carpet is formed that inhibits growth of underbrush. Combine this with a rocky outcrop of the Canadian Shield and you have a camper’s paradise. Hundreds of such campsites can be found scattered throughout the park, and it is not rare to travel for days without seeing another person.

These same portages and campsites were used by Aboriginal people for thousands of years and were visited by the explorers and voyageurs who traded with them in the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries. Rich in wildlife, the area was vital to the fur trade. Numerous references to the beauty and features of this land were mentioned in the journals of famous explorers and traders such as David Thompson and Alexander MacKenzie.

One of MacKenzie’s journal entries describes how Saganaga Lake was a cherished spot among the Native peoples: “The population was very numerous: this was also a favourite part, where they made their canoes, &c. the lake abounding in fish, the country round it being plentifully supplied with various kinds of game, and the rocky ridges, that form the boundaries of the water, covered with a variety of berries.”

These were the trade routes of the continent’s first economy, the highways of a fledgling nation before the automobile. Anyone who travels within the boundless territory is sure to feel an overwhelming sense of freedom and timelessness. The only schedules are self-imposed. Where, when, and for how long is entirely at your discretion, influenced only by the rhythms of nature just as it was for the inhabitants of the past millennia.

Year upon year those who have felt its power return, often for several weeks at a time, to explore the never-ending labyrinth of lakes. It is a time to re-energize, to endure hardship, to build physical, emotional, and spiritual strength. But most of all it is a time to grow: a time to feel alive in every sense of the word. Not a way to escape everyday life but instead a way to make sense of it and cherish it. Those who “disappear” to the north woods for a month at a time, sometimes by themselves, aren’t running away — they are returning home.

The motivation to return is best described in the essay “Why Wilderness?” by Sigurd Olson: “Ask those who have known it and have made it part of their lives. They might not be able to explain, but your very question will kindle a light in eyes that have reflected the campfires of a continent, eyes that know the glory of dawns and sunsets and nights under the stars.” This as much as anything describes the magic of Quetico.