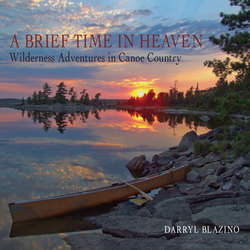

Читать книгу A Brief Time in Heaven - Darryl Blazino - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

WONDERFUL WILDLIFE ENCOUNTERS

ОглавлениеThat initial trip more than lived up to my expectations in regards to fishing and adventure, but I was caught completely off guard when it came to the profound beauty of the land. It took me most of the trip to adapt to the calmer pace of traversing by canoe and portage, but I was struck by two significant observations.

I had lived around similar lakes my entire life, but the towering stands of red and white pines that exist in Quetico were a complete surprise to me. My old motorboat haunts were either too far north for the big pines or, more commonly, had not escaped the saws of timber companies. These forests draw the amazement of travellers from afar, but I could not believe that such beautiful giants existed in my own backyard.

Secondly, I was taken aback by the cleanliness of the entire park. Those who frequent canoe country seem to treat the land as if it were holy. They talk quietly, respect one another’s space, and are very conscious of leaving the land just as they found it — pristine.

However, maybe the most surprising element of all was the wildlife that we came across. I could not get over the variety and frequency of wildlife encounters when travel is powered by foot or paddle. It is possible to see and hear more in one ten-day canoe trip than in years spent in a motorboat.

During that first trip alone we saw three moose, a deer, a snapping turtle, a pileated woodpecker, numerous osprey, painted turtles, beavers, bald eagles, ducks, dozens of loons, and a wide assortment of birds beyond my abilities of identification. In addition to this we heard a great horned owl hooting incessantly one afternoon (I had always thought them to be strictly nocturnal). In the years to come, these sightings would be the norm not the exception.

Bull moose, Deux Rivieres.

The most sought after encounter for visitors is undoubtedly the majestic moose. I have been fortunate enough to see more than forty-five moose during my adventures, with one trip yielding twelve sightings, but none of these was as impressive as the night we shared our campsite with the largest bull I had ever seen. It was the very first night of my wife’s very first trip to the park, and we had made it all the way to a small island on the south half of Twin Lake. I felt that camping near the entrance of the Deux Rivières, where I had seen moose before, would give us the best chance to observe these giant creatures, and this couldn’t have been more true.

On the first morning I walked on a small trail behind our tent to gather some firewood and noticed the fresh tracks of a very large moose. I was excited to confirm that at least one was in the area. We were soon off to the river with our camera at my wife’s feet. Around the very first corner we spotted a large buck with an impressive rack, but he darted into the woods before we could get him into focus. As we meandered along we spotted a beaver, a duck, some painted turtles, and an otter, but no moose.

When we returned to the entrance of Twin Lake, Michelle casually mentioned that when we left the site she hadn’t noticed the large stump sticking out of the water just off our landing. Then suddenly the “stump” moved. A giant bull moose with an enormous set of antlers was enjoying a picnic lunch of aquatic plants not more than sixty feet from where we had launched our canoe. We took several pictures as we inched closer and closer, until eventually he felt we had come close enough. He lumbered out of the water and made his way to the protection of the bushes and trees on the swampy section of our island.

After unsuccessfully trying to spot him and listening for his movements, we decided to go fishing. The moose remained hidden while we fished, but shortly after we began preparing supper we heard a giant splash. Sure enough he was back to the same spot. This time we decided to take turns: one watching him from the comfort of a rocky outcropping lakeside while the other cooked.

Nearly an hour passed as we spent dinnertime watching this magnificent bull. His rack had to have been nearly fifty inches in diameter. We were fascinated with the enormous musculature of his neck and shoulders and the silky sheen of his blackish brown coat. Soon the temptation of the perfect photo was too much to resist, and we were back in the canoe. Once again upon spotting us this giant was off to dry land. This time, however, he walked right across the island and swam to the mainland. As thrilled as we had been to have him around, we weren’t too sad to see him go. The thought of sharing this tiny island for another night with such an intimidating animal was a bit disconcerting.

Too Close for Comfort

A few summers ago, I guided a friend of mine and his cousin from Italy on a three-day trip. Again the Deux Rivières was on our itinerary, but being the middle of a hot July day I was hardly optimistic that we would see any wildlife. Water levels were low, requiring occasional poling. Beavers had constructed several dams along the way, making progress slower yet. Bend after bend we paddled, pushed, and lifted with not so much as a chickadee sighting. Finally, as we rounded the last turn, we came across a large cow moose.

She spotted us immediately, which led me to believe this encounter would be a brief one. Surprisingly, she continued sampling the vegetation and, instead of retreating, crossed the river at an angle that led her closer and closer to us. At the same time I had been creeping us forward, and at one point we were within fifteen feet with only a small beaver dam separating us. Soon, despite my efforts, our progress halted and in fact we began drifting backwards. My friend in the bow turned back and gave me a stern look. “We’re too close,” he muttered. He had dug his paddle under a log and was prying us away from this gorgeous animal. I had never been this close to a moose before or since and in retrospect can understand his trepidation — these are massive, powerful animals, but with no calf in sight and her ambivalence towards us I never for a second thought we had anything to fear.

After several minutes the cow crossed in front of us again and went ashore, but rather than head for the woods she walked around us and re-entered the water to taste the plants right behind our canoe! We photographed and videotaped and, more often, simply watched in disbelief for more than half an hour.

“Stefano, do you want to go pet it?” I inquired of our Italian visitor. “I can bring you closer.”

He declined, unsure if I was actually serious, but there is no doubt in my mind that we could have nudged her with our paddles if we had been so inclined. Mindful that we were the intruders and that we still had some real estate to cover before suppertime, we reluctantly left this rare close encounter and headed off.

Our adventure had a profound impact on Stefano. I will never forget his wide-eyed grin and his fascination with his new surroundings. I don’t think he had ever been outside of Italy before, and his enthusiasm, not to mention our good fortune, made the trip a very special one.

And Then There Were Five

In the spring of 2000 we decided to get our permits in advance and enter via a rough logging road to Bemar Lake on the east side of the park. Just before reaching Saganagons Lake, in a narrow weedy area, we saw a mother duck with six cute little ducklings. We followed them for a time, delighted to see such a pleasant family going about their business.

Just as we were overtaking them, a loud splash was heard. I was the only one of our group of four who was looking the other way at the time. The others confirmed that I had seen only the tail end of a rare but brutal event. A large northern pike had come to the surface and taken one of the ducklings! Surprisingly, the other ducks continued on as if nothing had happened. Although far from being the most enjoyable experience we had witnessed, it was quite fascinating nonetheless.

In a similar event, two of my canoeing partners stayed at camp at the south end of Russell Lake while Rod and I went for an evening fish. Upon our return they excitedly relived a strange event for us. While standing on shore they had noticed several scattered ripples and then bubbles developing at water’s edge. Soon a frog emerged from the water and onto the rocky shore. Suddenly a huge bass flung itself a full six inches onto shore, capturing the frog in its mouth before shimmying back into the water!

Where Eagles Soar

Virtually all of our trips involve sightings of at least one bald eagle. These once rare birds are now a very common sight in canoe country. With their remarkable eyesight, it is usually the eagle that will spot you first, as my wife and I found out when we turned the corner from Russell Rapids to Sturgeon Lake. Being preoccupied with our ride down the strong current we were startled to hear what sounded like a kite cutting through a strong wind. We looked up to see a giant pair of yellow feet with razor-sharp talons a mere dozen feet above our heads. It was obviously a false charge, but if the eagle had been serious, we probably would have abandoned ship — that is, if we weren’t paralyzed with shock.

Sometimes, however, these giant raptors aren’t the toughest guy on the block. While on the south end of Walter we were stunned to see a herring gull (commonly referred to as a seagull) attacking an eagle. We conjectured that the eagle had attempted to steal the gull’s supper and the gull wasn’t giving up without a fight. Whatever the story, after several confrontations it was the gull who got its way with the eagle flying off in defeat without dinner.

Even more shocking was the time on Pickerel Lake when my wife and I saw an eagle being chased off by a kestrel hawk. This small but aggressive member of the falcon family (also known as the sparrow hawk) was much less than half the eagle’s size, and yet it was able to drive off the eagle, likely from its nest. By no means did the eagle seem frightened by the tiny hawk, but it did make a steady retreat without any hint of a counterattack.

What made the encounter even more peculiar was that every time the kestrel approached, the eagle would do a complete barrel roll! This happened on at least six consecutive occasions. The kestrel pursued the eagle and just at the instant of attack the eagle pulled its long, sweeping wings in and did a complete spin, dropping down a fair distance and creating separation between them in the process. Over half a mile later the hawk finally relented and headed back towards its nest, point well delivered.

Only once have I had the thrill of seeing an eagle take a fish from the lake. In 2010 we were crossing north on Minn Lake when we spotted a white head perched on the tallest pine off the point of an island. Eager to use my telephoto lens I asked my paddling partner to see if he could work us closer while I set up my camera. No sooner had I picked up the case than the eagle swooped down from its perch, touched the water with one precise motion, and soared off with a small fish clasped in both its talons. What a sight to behold.

Bald eagle, Fern Lake.

Bears in Their Backyard

Most people are well aware that bears have excellent climbing skills but don’t realize that they are proficient swimmers as well. The first of only two bear encounters that I have had over the twelve years I have been exploring the park was quite memorable. While paddling down the west arm of Fern Lake we noticed two dark objects crossing the channel ahead of us. As we drew closer, the bears (a sow and a cub) took notice and hurried their already rapid pace to roughly equal that of our canoe. Obviously they felt a bit safer on land and were determined to get there as quickly as possible.

Bear cubs, Bud Lake.

There was one small problem regarding their exit, or so we thought. They were headed for a small but completely vertical rock cliff which seemed to lack any apparent ledges that would facilitate their exit. We stopped to watch what we believed would be a lengthy struggle. To our astonishment, the mom and her small cub climbed the rock face without the slightest hesitation. To them it must have seemed as routine as ascending a set of stairs. With their wet fur tight to their bodies, you could see the extensive musculature beneath. Needless to say we have an even greater respect for these powerful and nimble animals after seeing their abilities first-hand.

Coincidentally, my second bear sighting six years later was just a mile north of Fern on Bud Lake, and it was even more incredible. As we headed north we rounded a point and heard quite a racket. It sounded like the squawking of ravens but turned out to be three tiny cubs displeased with their mother. We will never be certain if mom was giving her cubs a swimming lesson, but it seemed to be the most logical explanation for what we saw. Initially mom and two of the cubs were swimming (actually, one of the cubs was hitching a ride on her back) to a small rock island a mere thirty feet from the mainland. The third cub was already on the island.

After a moment mom swam back to shore and appeared to be waiting for the little ones to follow. The cubs once again loudly voiced their displeasure. With much hesitation, one by one, the cubs began heading back to mom, crying, sometimes gurgling, the entire time as they made the arduous crossing.

Even though we understood that mom had their best interests at heart, it was quite unpleasant hearing the cubs in such distress. We realized, however, that we had been incredibly fortunate to see such a rare and intimate event.

Elizabeth Lake Predator

Most instances where people are attacked by black bears involve a mother protecting her young. If a bear hears you coming it will usually retreat. Surprising a bear, however, can incite an attack response, especially if cubs are around, and there are dozens of well-documented cases where such has occurred.

Predatory black bears (a bear that will stalk and attack a human), on the other hand, are extremely rare. There have been approximately half a dozen documented instances of a predatory black bear killing a human. When you consider how many hundreds of thousands of people every year venture out into the wild, this is an absolutely minuscule number, yet psychologically it is one that is difficult to ignore.

The cornerstone of bear safety is to keep a tidy campsite where food scraps are burned and dishes washed. Covering the food packs with tarps or hanging them at night will also lessen the risk of bear encounters. These habits are completely second nature to us, and thus I have to admit that the thought of being attacked by a bear rarely crosses my mind. I wish I could say this was true for the night we spent on Elizabeth Lake.

The evening would have been memorable for all the right reasons: a perfectly calm, gorgeous evening, like so many others, with Roddy and I leisurely touring the shoreline. As the sun brushed the tops of the tallest pines, the silence was broken by a thunderous sound.

Crraaack-thuuddd! A sizeable tree fell to the ground only a few hundred yards from our campsite. Startled, we pondered how, with barely a breeze in the night’s air, this could have transpired.

“You know, a bear will push a tree over sometimes searching for grubs,” Rod offered as an explanation.

Again silence. We paddled on a little longer before returning to our home for the night. After relating our experience to Joe and George around the campfire our conversation drifted to more worldly topics before retiring to our humble abodes.

It was quiet for quite a while when a rustling of sorts, possibly followed by the crack of a twig, was heard. It was just loud enough to get our attention. Neither of us spoke, but I could tell Rod was straining his ears as he angled his head up and then froze.

Soon there was more rustling and then a distinct but subtle snap. There was no doubt: something was definitely out there, and whatever it was it was getting closer!

We called to our companions in a loud whisper: “Guys, I think there’s a bear out there! Don’t you hear it?”

With overwrought ears we sat up in our tents until all doubt was removed. Something was in the woods near our tent. All of us agreed to get up and investigate.

What a sight we must have been. The four of us — wearing nothing but boxer shorts and armed with an axe, a stick, a filleting knife, and a whistle — ready to do battle with a ferocious man-eating bear. Hearts racing and poised for the attack we glanced back and forth, pondering our next move. After a minute or so of inaction we finally considered the possibility that it might just be a squirrel, a bird, or any number of living creatures that are no threat to our well-being. But we wouldn’t take any chances.

“Should I blow the whistle?” Rod inquired meekly.

“Sure, why not?” we agreed unanimously.

Well, at least I thought it was unanimous. Apparently George had not heard the question because when the ear-piercing blast came it nearly gave him a heart attack. He jumped about a foot off the ground and, still bewildered, turned to chastise Rod: “What the heck did you do that for?”

Joe and I were already in stitches before Rod deadpanned his response as if he were a referee: “George, you were offside.”

We doubled over in laughter and were in tears most of the night. Unbelievably, it wasn’t until recounting these bizarre events the next morning that we even considered the obvious fact that most certainly it was a beaver that had felled the tree.

I still get a chuckle whenever I think back to how ridiculous we were that evening.

Loons Gone Wild