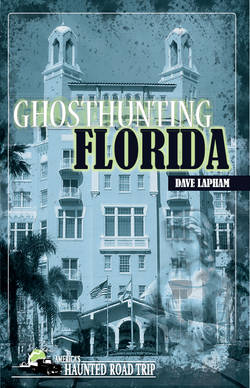

Читать книгу Ghosthunting Florida - Dave Lapham - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 4 Audubon House & Tropical Gardens

ОглавлениеKEY WEST

I WAS STANDING ON THE SIDEWALK with a group of people, talking to Jon Engel, our ghost tour guide from The Original Key West Ghost Tours, when there was a commotion on the far side of the group.

“Look! Look!” someone called out.

We all turned to see what the person was so excited about. The man and his two companions were pointing at a third-story window.

“What are you pointing at?” everyone began to ask.

Breathless, he said, “There was a small face in that upstairs window. It was looking down at us, and then it just disappeared. We all saw it.” The other two nodded in agreement. They’d seen it, too.

Jon smiled. He hadn’t even started talking about the Audubon House where we stood, and already things were happening. Sometimes on the tours people saw curtains moving, which might well have been caused by the air conditioning, or an occasional light switching on and off, if anything. But this was great. It was fun for him to watch people’s reactions, and it was good for business. He knew Brant, his boss, would be pleased to hear about this experience.

After the excitement died down, Jon began his talk.

“Looks like the ghosts are trying to preempt me this evening,” he laughed, “but, ghosts aside, this house—the Audubon House—has a fascinating history.”

The house had been built by Captain John H. Geiger, a prosperous harbormaster and wrecker, one of those daring men who braved pirates and sometimes stormy seas to rescue passengers and salvage cargo from scuttled shipwrecks. Some think it was built in 1830, because in 1832 John James Audubon visited the Florida Keys and the Dry Tortugas aboard the Revenue Cutter, Marion. He allegedly sighted and drew eighteen new species of birds, many in the one-acre garden of the house, while he resided there as a guest. Research of tax rolls, deeds, and old newspaper articles, however, strongly suggests that he did not. His writings reflect that he stayed aboard the Marion to avoid the “fevers,” as he had promised his wife. Also, he never mentioned the Geigers or the house in any of his writings. Also, the style of the house is American Classic Revival, and it was almost certainly built after the disastrous hurricane of 1846, probably about 1850, but not in 1830.

In 1829 Captain Geiger married Lucretia Sanders, a woman from the Bahamas, who bore him twelve children. Captain Geiger and his wife both died in the house, as well as five of their children, one falling from a tree in the garden. Geiger descendents lived there until 1956, the last being Willy Smith.

After Mr. Smith died, the house sat empty for two years. It was saved from demolition by Colonel and Mrs. Mitchell Wolfson, who purchased it in 1958, renovated it, and opened it as a museum in 1960. The house was Key West’s first restoration project and is still considered the crown jewel of all of the island’s restoration efforts. The house has been furnished with twenty-eight first-edition Audubon paintings and with furniture typical of the prosperous elegance of nineteenth-century Key West. The garden, too, was restored to historic authenticity. It is now run by the Mitchell Wolfson Family Foundation as a nonprofit, educational institution, which provides tours of the house and garden and conducts art classes.

And there are the ghosts. I talked to Robert Merritt, the operations manager, who gave me much more of the history of the house. He admitted that from time to time inexplicable things happen. Light bulbs are unscrewed. The rocking chairs on the porch rock back and forth on their own.

He told me that recently, while he was closing up one evening, he found beads from one of the several festivals on the island scattered around the living room floor. He surmised that some child had broken the string and just left the beads strewn around the room. He picked them all up, threw them in the trash, and finished locking up. He never gave the beads another thought. When he returned the next morning, he discovered the beads again scattered about the living room floor.

Visitors sometimes hear children laughing on the third floor or whispering to each other. And, of course, there is the occasional face in the window that I almost saw. In fact, the third floor might well be heavily haunted.

During the 1800s, yellow fever epidemics regularly swept across the Keys, one of the reasons Audubon’s wife didn’t want him to stay ashore when he visited in 1832. When you contract yellow fever, time is the only cure. If you catch the virus, which is transmitted by mosquitoes, your body either destroys the virus or you die. And yellow fever is very contagious. So when one of the Geiger children got sick, Mrs. Geiger isolated the child on the third floor of the house. Several of her children were infected with yellow fever; four of them died.

Willy Smith, the last Geiger descendent to live in the house, was an eccentric recluse, so the story goes. No one knows for sure when his peculiar behavior began, but in adulthood he never left the house. He seemed to spend most of his time on the second floor, where passersby would often see him looking out the window. The water and electricity in the house had been turned off, so he would lower a basket from a second floor window, and people would put food and water in it. Then he would hoist the basket back up. That was his only communication with the outside world.

Many years later, after the house had been restored and had become a museum, a wedding party reserved the house for a reception. The staff gave them a tour of the house. The whole house had been elegantly lighted with soft lamps and candles. When a group of guests went into what had been Willy’s room on the second floor, the flames from the two candles burning there began to dance around the room, much to the fascination of the visitors. When the flames finally stopped moving, still separated from their candles, they formed a cross.

Willy was probably not the cleanest person. Occasionally, when a docent takes a party upstairs and into Willy’s room, a strong scent of urine pervades the area. Fortunately, the docent will simply say in a stern voice, “Willy, get out of here and don’t bother us,” and the smell dissipates instantly. Willy appears to be as reclusive in death as he was in life.

But perhaps the most bizarre story concerning the Audubon House is about the doll, variously called Mrs. Peck, Bye-Lo Baby, and the Demon Doll. Lore has it that the doll was made in England in the middle-to-late 1800s. The fashion at the time was to use a painting or oil-o-gram of a person, often a baby or young child, and create a doll in its exact likeness. This was especially popular when a young child had died.

When this particular doll was completed, it was placed next to the dead infant from whom it was copied, and no one could tell the difference between the two. Some speculate that the spirit of the deceased infant entered the doll. Others think that perhaps the spirit of one of the dead Geiger children possessed it. No one knows how the doll came into the Geigers’ possession. In any case, someone in the Geiger family put the doll in a baby carriage in the third floor quarantine room, and many people insisted that its eyes followed them as they walked around.

Apparently, the doll did not like to be photographed. At one point, after the house had become a museum, its security system experienced a rash of what was thought to be false alarms. Each time the police and the museum director responded, but each time nothing had been taken, and there was no evidence of forced entry. Still, as a precaution, Bonnie Redmond prepared a photographic inventory of all the dozens and dozens of items in the house. When she got the photos back, she was stunned. All of the pictures of the doll had thick, black marks across their faces, as if Mrs. Peck were saying, “No pictures.”

A few years later a BBC reporter working on a documentary of Key West came to the house. He took numerous pictures and interviewed several staff members about the history of the house and all the antiques, and he asked if there was anything unusual about the place. When the staff told him that they had a haunted doll, he laughed.

“You Americans, always making jokes.”

At the end of the day, the Brit left the house, threw his camera and notebook in the passenger seat, and drove off. A half-block down Whitehead Street, his camera case popped open, the film fairly jumped out of the camera, and the roll of pictures he had just taken of the doll unraveled, destroying all the exposures. Needless to say, he was unnerved. He returned reluctantly the next day to reshoot the pictures he’d lost, but the doll was gone. Did a disgruntled docent remove her, or did she decide on her own that she was tired of being photographed? No one has ever figured out where she went, and there has never been any evidence to indicate what might have happened to her. The Weekly World News offered a five-thousand-dollar reward for the doll, dubbing her the “Demon Doll,” but she is still out there roaming somewhere, the reward never having been claimed.

Even though the doll has left the premises, Willy Smith and the Geigers have not. The house continues to be very active. When Bob Merritt talks about the Audubon House he stresses the history and opulent décor—but he does admit it is haunted.