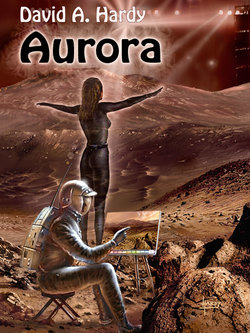

Читать книгу Aurora: A Child of Two Worlds: A Science Fiction Novel - David A. Hardy - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE MUSICIAN

“Spare us a couple a bob, mate? Just enough for a cup of coffee?”

The girl couldn’t have been more than fifteen. Her face was thin and drawn—and dirty—yet she was pretty in a pale, elfin kind of way.

“You mean ten new pence, don’t you?” grinned Lefty. “Well, I was just going to the pub, as it happens. I’ll buy you a Coke, if you like, if we can get to the bar before they close.”

“Coke? Oh, wow! Yeah, all right, then. Why not?”

Five minutes later Lefty was gazing in awe as she downed a large gin and tonic in one swig.

“You’ll get me arrested,” he said. “Buying alcoholic drinks for minors.”

“I’m not a minor. Don’t you worry—I’m old enough.”

“Yeah, yeah, and I’m the Duke of Edinburgh. I just hope you can prove it if the Law comes snooping around.” He stuffed a wad of banknotes into his inside pocket.

“You’re a bit flush, aren’t you?” she asked, cocking her head.

“Just been paid for a job.”

“Oh yeah? What do you do then, this time of night? Burgle houses?”

“Ha, ha. No. During the day I’m self-unemployed. But I’m in a band—the Gas Giants, heard of us? We’ve been getting quite a few gigs in the evenings.”

“Funny name. No, I never heard of them. Why’re you called that?”

“Oh, some of the outer planets are called gas giants ’cause, well, they’re just big balls of gas. That’s us!” His white teeth shone. “No, it just sorta sounded right—we play “spacey” sort of music—one day we’ll show Pink Floyd and Hawkwind how it’s done—and ‘it’s a gas’. You know?”

“Not really. What do you play?”

“Bass guitar. I’m left-handed—they call me Lefty—and just to be really different I tune it E, B, G, D, like the top four strings on an ordinary guitar, only back to front. I can really leap around on it though!”

“If you say so. That stuff’s all Greek to me. I don’t know anything about music. Pop all sounds the same, and the stuff they play on Radio Three’s boring. Mind you, a boy took me to the Last Night of the Proms once.” Her face, which had been almost sullen, brightened. “Now that was great. Not the music so much—it didn’t mean much to me, really—but all those people, enjoying it together. I’ve never known anything like that. Except....”

“Except what?”

“I dunno. Something I seem to remember. But I can never seem to get a handle on it. You know what I mean?”

“I suppose. Well you must come to one of our gigs, then you’ll see what it’s all about.”

“Maybe. Can I have another drink?”

“Eh? Oh, right, sure.” He sneaked a glance at her unusually pale, almost violet eyes, set in dark hollows. He couldn’t quite figure her out. Under the grime she was really very good-looking, with her long, very blonde hair, but sort of remote. And she was so slim as to be almost twiggy. Perhaps she’s been ill? he wondered.

As he got up the barman shouted, “Last orders please, ladies and gents!” It was already 10:40 p.m.

“Better make it a double then,” said the girl with a grin.

“Do you think you oughta drink so much?”

“Habit,” she replied without apparent offence. “It doesn’t help, though. Neither does anything else I’ve tried. Once I thought acid was the answer, but....”

“What are you trying to find? Drugs aren’t the way, you know. Oh, yeah, I tried them too—took me two years to kick them for good. Cold turkey...ugh.” Lefty shuddered. “If it’ll help you to talk about it, though, go ahead. I’m a good listener, they tell me. Hey, listen, I don’t even know your name...?”

She put her hands behind her neck and piled her hair on top of her head. It suited her, thought Lefty. Made her look older.

“It’s Aurora. Don’t you dare laugh.”

He raised an eyebrow but said nothing.

“Oh, I don’t know myself what’s wrong with me. I always feel there’s something missing, that’s all. Whatever I do, I don’t seem to belong.”

She paused for a long moment, eyes closed, until Lefty thought she had fallen asleep. Then she continued, drowsily.

“My dad died in the war. I almost did too, so my mother told me—in the Blitz. We moved back up to Scotland after the war—near Inverness.”

“Inverness? Wow—Swingsville! So what brings you back here?” asked Lefty. Then he frowned. “Hang on! What do you mean, you were in the Blitz? That’d make you over thirty! Come on, there’s no way you’re more than sixteen. Eighteen, tops. What’s your game?”

The girl–woman called Aurora gave him an enigmatic smile. “No game. I don’t tell many people, and to be honest I don’t know why I’m telling you, but I’m thirty-two. Yes, on the level.”

Lefty gave her a long, hard look, then shook his head as if pestered by a fly. “Yeah, right. Go on, then. You were saying—?”

“Mum died when I was ten, in a car crash. I got out without a scratch. But I didn’t have any other living relatives except my older brother, Steve. We were in and out of children’s homes until I was fifteen. I kept running away. I was good at school, or I was whenever I bothered to go. The problem was, I found lessons too easy. The other kids thought I was a swot, and the teachers couldn’t handle me. So I used to bunk off. Except for science—I liked that. I was good at art too. Of course, even that threw them into a tizzy, ’cause you weren’t supposed to be good at both. Steve would have been OK if it hadn’t been for me. He’s a worker. He’s settled down with his own family now—haven’t seen him for years.

“Anyway, after that I could never seem to hold down a job for more than a week or two.” Then, in a sudden rush, she added: “I always seem to cause trouble, wherever I go. You’ll see—you won’t want me around for long, either.”

She started to rise, ready to leave, but Lefty gripped her arm. “Where’re you going? You got a place to stay?”

“Oh, sure, I’ve got a nice comfy cardboard box on the Embankment. As long as somebody hasn’t beaten me to it....”

“Come on, I’ll take you to my pad. You could do with somethin’ to eat, anyway. It’s all right—I’ll sleep on the couch.”

She looked at him doubtfully for a moment, then came to a decision.

“Sure. Why not? Thanks.”

Outside, it was raining heavily. Lefty hailed a passing cab but it sailed on past, its wake drenching them.

“Come on, it’s not far,” he yelled, grabbing Aurora’s hand, his head down. “We can walk. Run.”

Minutes later they were scampering up half-a-dozen worn, chipped concrete steps and passing through a door still boasting a few shreds of brown paint. Then up four flights of twisting, lino-covered stairs, then another door, which Lefty kicked just below the handle. It flew open.

“It’s not much, but it’s home, to coin a phrase,” Lefty said with a grin. He reached for a box of matches on the cast-iron mantelpiece and shook it, then bent down and lit the gas fire.

“Look, you really oughta get out of those clothes. They’re as wet as if you’d jumped into the Thames. If you....”

He stopped in surprise as, with a few deft movements, Aurora shrugged out of her clothes and draped them over a chair near the fire. That done, she flopped naked into another chair in front of it. Against the segment of dark sky framed by the dirty, rain-streaked window, her face and body reflected the warm orange glow of the gas fire.

Lefty hastily looked in the other direction, pointing. “That’s—er—that’s the piano where we do most of our songwriting. The rest of the guys have got flats in this dump, or just down the road. There’s the bathroom; you have to pull the chain twice to make it flush. No shower, but there should be hot water if you want a bath. The bedroom’s through there. I can probably find you a pair of pajamas if you....”

“No, thanks. I never bother, not when I’ve got a proper bed.”

“Oh, man!” Lefty raised his eyes heavenwards. He reached inside the bedroom door and pulled a string which hung there. An unshaded orange bulb clicked on over the bed, and he picked up his pajamas from a heap on the floor.

“Sleep well,” he said through a yawn as Aurora passed him on her way in.

* * * *

He raised his head groggily and pried open his bleary eyes. What had woken him? Someone must have turned on the radio, for there was tinkling music coming from behind him. Something on Radio Three? Classical, yet a bit avant-garde? Normally the dial was never moved from Radio One. It seemed a bit loud and clear for the old trannie, though. He levered himself up and peered over the back of the sofa.

Aurora, wearing only briefs and bra—but at least she’d got something on—was sitting at the piano, her fingers flickering over the yellowed keys, her face trancelike.

“Hey—you never told me you could play!” Lefty yelled, louder than he had intended. “You said you didn’t like music much! So where’d you learn to do that?”

The girl started violently and drew back her hands as though the keys had suddenly become red-hot. “I said I didn’t like the music I’ve heard. I’ve never had a chance to play an instrument myself before.”

“Oh, sure. Now pull the other one—got bells on it!”

“It’s true.” She looked at him blankly. “Why not? You just find out where the notes are and then play them, don’t you?”

“Yeah, right on. Except that most people take weeks just to learn the basics—and some have lessons for years and still never get further than ‘Jingle Bells’....”

“Well, p’raps I’m just a natural, then. Some people are, aren’t they?”

“So the story goes,” said Lefty dubiously. A moment later the door sprang open with the inevitable crash and four men, all aged between twenty and thirty, burst into the room. They screeched to a halt on spotting Aurora, and began making exaggerated motions of backing out of the door again.

One of them, who sported an Afro hairstyle in bright red hair, said with a grin, “Hey, sorry to break in on your scene, man!”

“Like, we didn’t know you’d got company!” added the one with a droopy, Mexican-style moustache.

Lefty glowered, but before he could speak Aurora snapped: “I don’t know what you’re all staring at. But, if you’re embarrassed, I’ll go and get dressed.”

She left the room with a histrionic sigh. The five young men exchanged guilty looks, wondering what it was they should be feeling guilty about.

A minute or two later she reappeared wearing her jeans, now dry and stiff.

“Perhaps I can do the introductions now,” said Lefty with a flourish, as the door opened and a youth with shoulder-length dark hair strolled in. “The latecomer, as usual, is Synth. The rest of this mob”—he pointed—“are Ginge, Doug, Acker, and Herbie. Herbie’s our road manager, but he doubles on guitar as well. Guys, this is Aurora.”

He didn’t explain further. The others seemed immediately to accept her presence as one of the gang.

“Hey, the new synth’s arrived,” burst out the newcomer. “It’s just got to be stacks better than that old thing I cobbled together.”

“It better be,” grunted Acker, “after we’ve sold all our worldly goods to pay for it.” He grimaced at Aurora. “Just to put a deposit on it, even.”

“Synthesizer? Oh—is that why you call him Synth?” Aurora whispered to Lefty. “I thought perhaps he was—you know....”

Lefty smiled. “Don’t let him hear you say that!” He continued more loudly: “This one’s polyphonic—not like the old Moogs.” He pronounced the name to rhyme with “rogues”.

Aurora looked totally blank. “Sorry, mate, but I haven’t a clue what you’re talking about.”

“Oh, yeah, I forgot—you aren’t into our kind of music, are you? Well, on the old Moog synthesizers you could only play single notes. If you wanted to record something like Walter Carlos’s album Switched-On Bach you had to keep overdubbing—re-recording from one tape to another—to get the harmonies and so on. But we’ve just got hold of one that plays chords. And it’s really compact as well.”

The group fell to discussing their gig that night and Aurora roamed around the room, taking science-fiction paperbacks and magazines from the shelves that lined the walls, and staring with a puzzled expression at the star-charts and maps of the Moon and Mars, and at the big art print of a planetary landscape with a huge red sun looming in its sky, bearing the title Stellar Radiance, that filled the rest of the wall-space along with faded posters of rock bands in concert. Someone had turned on the old radio, and they took a brief interest as a news bulletin announced that Apollo 16 had landed safely at Descartes. Lefty bemoaned the fact that the next Moon landing could well be the last manned space mission for decades if not forever. “We should be going on to Mars—that’s where it’s at,” he stated decisively.

Aurora blinked, as if coming out of a reverie, as Ginge called: “See you in the grotty club—sorry, Grotto Club—tonight, then.”

“Who, me?” she said.

“Well you want to see what we can do, don’t you?” said Lefty.

“Oh, well, s’pose so. Why not? I’ve got nothing better to do.”

“Cor, such enthusiasm! You’ll see—one of these fine days you’ll be boasting about knowing us when we were just starting out!”