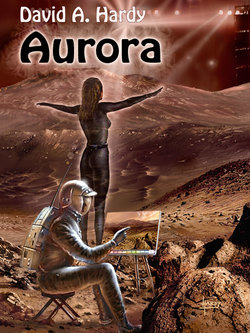

Читать книгу Aurora: A Child of Two Worlds: A Science Fiction Novel - David A. Hardy - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеROCK

No doubt, if the light of day were ever admitted, the Grotto Club’s decor would have looked cheap and shoddy; but in the pulsing shadows cast by concealed blue, green and ultraviolet tubes it seemed an ideal setting for the Gas Giants. Boulder-shaped tables and chairs crouched beneath papier-mâché arches; stalactites hung from the ceiling. Aurora hesitated as she entered through the skull-shaped doorway, almost as though afraid to step inside. Then she threaded her way to a table near the stage, along the front of which was draped plastic ivy, glowing a vivid green in the hidden lighting.

The club was only half-full so early—it was barely ten o’clock. At the side of the stage an elderly man in evening dress was playing Top Twenty tunes from six months before on an electric organ. Lefty had told her that the guy had used to own the club when it was a much more respectable and staid affair, and had been allowed to stay on as “resident organist” as part of the deal when he was forced to sell it. The rest of the clientele secretly laughed at him, but it didn’t matter. He was almost completely deaf.

On the darkened stage itself, her new friends were busily setting up their equipment, of which there seemed to be a great deal. The organist looked round in annoyance as a loudspeaker gave a loud pop! which even he could hear, and a sibilant, echoing voice chanted: “Testing. Testing. One-two. One-two.” The synthesizer emitted a sound that Aurora mentally likened to a constipated duck; then, as Synth moved what looked like pegs on a complicated Solitaire board, it gave forth a piercing shriek, this time more reminiscent of a cat whose tail had been yanked. This was too much for the organist, who got up and left, scowling.

The tables filled up. For a while the only sounds were the hubbub of voices and the clinking of glasses. The air became smoky, and Aurora noticed a strange, sweetish aroma which was not tobacco, but which she recognized only too well. Someone lit joss sticks near the front of the stage. Then, without warning, came a whispered “One, two—one, two, three, four!”—followed this time by a staccato rattle of snare drums and a wall of sound which drowned out all conversation.

Or should have done. Looking about her, Aurora noticed that somehow most people seemed to manage to keep talking to each other as if nothing had changed.

She sat forward expectantly, but soon sank back into her seat. This was nothing but noise to her. The bass boomed, and occasionally an interesting little phrase from the lead guitar would break through, but when the synthesizer could be picked out at all it sounded like a fairground organ. The piece ground to a ragged close and received a few desultory claps from the audience. Next came a slow, turgid and apparently endless composition, throughout which the synthesizer made sounds like rushing winds or waves, but with no obvious relationship to whatever else was going on. When this dirge finally stuttered to an uncertain finish there was no applause.

And so it went on. Her mind began to wander. Lefty had remarked to her that they had started out as “pretty much your standard heavyish rock band”, and the description appeared all too accurate. He seemed certain that, when they could afford all the equipment they needed and time in a recording studio, they would take the charts by storm with a single, followed up closely by an album. “Of course, the single’s only for the publicity—Top of the Pops and all that, you know. And the money, of course. We’ll be an albums band really.” She had gathered that he was a bit worried about Synth, who “fancies himself as a dab hand at the old electronics, but he’s a pretty ordinary keyboards player really. Maybe he’ll improve with practice. I hope.”

Aurora was actually leaving her seat to go when Lefty caught her eye and jerked his head back in a “come here” gesture. She walked forward and, still playing, he squatted at the front of the stage, putting his mouth close to her ear.

“It’s not going too well tonight—there’s just no feedback from the audience. It’s like that sometimes.” She had to strain to hear his voice. “...and Synth hasn’t really got the hang of his new toy, though he’s been playing with it all day. It’s not helped, of course, that he’s got himself half-stoned on a bottle of the old vino while we were setting up. Feel like having a go?”

“What d’you mean? Play up there? Me? I couldn’t!” Aurora whispered, then shouted above the racket: “There’s no way I could play that thing! Especially in front of an audience.”

“Come on,” ordered Lefty, grabbing her hand and abruptly standing up, so drawing her up onto the stage whether she wanted to be there or not.

“Just do what you did on the old joanna this morning. Let’s face it, you couldn’t make it any worse, could you?”

Synth allowed himself to be dispossessed with less objection than might have been expected, and went off to find more wine. Aurora stood in a pool of blue light, surrounded on all sides by humped black shapes with glowing, winking red eyes, some emitting, at this close range, baleful hisses or throaty hums. She wanted nothing more than to fly out of the gaping door and lose herself again, wandering as she had wandered for half her aimless life.

“I don’t know what to play—I don’t know any of your bloody tunes!” she wailed.

“Just play anything, but do it,” hissed Doug from behind his mountain of drums and cymbals. “‘Baa Baa Black Sheep’, if you like. We’ll jam around it.”

Ginge played a couple of rapid scales on his guitar, establishing a key, and Acker followed him on saxophone. She tried an experimental note or two, a chord, and almost reeled at the blast of sound from the PA system around her. Herbie leaned over and touched a knob. “That’s the gain control. Volume, OK? This”—he rotated a miniature joystick—“is for the quad effect. Quadraphonic? And this slider’s the note-bender.”

Volume she understood; the other terms might as well have been Arabic. She turned down the knob, gave herself a quick private recital, then fiddled with the miniature jack-plugs on the Solitaire board for a moment. Finally she turned the knob back up, sighed resignedly, and announced: “OK. Here goes nothing.” The audience ignored her.

Within three bars not a word was being spoken in the crowded room. Glasses paused motionless on their way to lips; chicken nuggets lay congealing in baskets. The room was filled with the sound of clear, ice-cold crystals being struck by an elfin hammer in some subterranean cavern. Suddenly the tawdry artificial surroundings were real, glistening rock.

Aurora’s left hand moved to the control board as if of its own volition, and the sound of a faery choir joined in, swelling and soaring.

At first the electronic notes rose alone, shivering and cascading from the fake icicles hanging from the roof. Then, tentatively, the snare drums struck up a rhythm. At first it sounded crude, clumsy, and out of place, but soon Doug was weaving an intricate tattoo with brushes and cymbals. He beamed with pleasure as he became aware of Lefty’s electric bass tracing a lattice pattern of sound in and out of his own. Ginge’s foot rose and fell on his wah-wah pedal as his old Fender made soft, plaintive sighs such as his fingers had never evoked before. Acker had switched to a flute, producing birdlike trills and arpeggios. As for Herbie, he stood stock-still, mouth wide open, his acoustic guitar trailing from one hand.

As the last few notes dripped from the speakers there was silence. Several women and one or two men were openly crying. Then someone began to clap, hesitantly, and the applause grew into a storm. Aurora blinked, seeming to emerge from a daze, and managed a wan smile. She looked drained.

Lefty seized a microphone and said, stumblingly: “Er—thanks. This is, um, Aurora. Give her a big hand, folks—she’s only been sittin’ in with us tonight. First time in public. But we hope it won’t be the last. Don’t we?” He looked over at her pleadingly, his words drowned in cries of “More!”

The next melody started like a toccata, but as it progressed and the other musicians joined in it became ever more lively and happy. The audience began to participate, clapping and swaying. A few couples began to dance, until the whole room was in motion. Aurora discovered that the quad lever sent her notes swooping and circling around the room from strategically placed speakers. Herbie vanished backstage, and soon two strobe-lights began to flash, one at each side, so that the dancers’ movements seemed jerky and spasmodic, as if they were stiff-jointed puppets or part of a film shown at the wrong speed.

Then, just as the music seemed about to reach a crescendo of joy, there came several jarring discords and Aurora slumped lifeless across the keyboard.

* * * *

Thousands of white-gowned people sat around the huge amphitheater, some with eyes closed, just listening, others watching entranced as the musicians played. Each musician wore his or her instrument lightly, from a cord around the neck or a belt at the waist; yet the sound filled the vast natural crater with its carved seats, and overflowed and spilled into the surrounding countryside.

In the Old People’s village, those who no longer wished to travel beyond their own homes sat outside their domed houses, nodding and smiling with memories of many past MusicFests.

The sky deepened to a beautiful, transparent violet. A golden disc rose. At first it seemed like a moon, but then it evolved into a floating craft. As it rose higher it passed into shadow and darkened, as if in eclipse. On the northern horizon a glow appeared. A bright spark detached itself and ascended into the darkling sky. As Aurora watched, it dimmed to red, brightened briefly, and was obscured by vapor. From the dark disc, anxious eyes stared down at her....

* * * *

Aurora coughed slightly as Lefty exhaled smoke from his cigarette in a sigh of relief. He stubbed out its red glow in a saucer. “Cripes, we really thought we’d lost you too there for a minute,” he said.

She gazed around her. She lay on a spotlessly clean white bed. Beyond the circle of pale, anxious faces—and Lefty’s dark anxious face, though even that looked pale—was only a further white circle that she recognized after a moment or two as a hospital screen. Lefty, Ginge, Herbie, Doug, Acker. Plus a nurse and a tall man in a white coat.

“Where’s Synth?” she asked, struggling to sit up. “What do you mean, lost me too?”

“Nothing. Nothing.” Lefty made a move to light another cigarette, but the nurse caught his eye and frowned.

“If you don’t mind, Mr. Clemson, I think now that you know she’s all right.... In fact”—she looked questioningly at the doctor, who nodded—“it would be best if you all left now and let Miss—erm—Aurora rest.”

“No!” cried Aurora sharply, “Where is Synth? I want to know—right now—or I won’t rest. Something’s happened to him, hasn’t it?”

“No, he’s fine,” said Lefty. “But he’s left the band—walked out while you were still playing last night, tell you the truth. He’s stripped his flat. The manager at the Grotto says Synth told him...well, that you made him look like an idiot. But that wasn’t your fault—he is an idiot.”

Aurora hid her face in her hands. “Yes, it was my fault,” she sobbed. “I warned you, didn’t I? I told you I’m always trouble and you wouldn’t want me around....”

Ginge stepped forward before anyone else could speak. “You couldn’t be more wrong there, gal. Something good happened while you were around us. Real good. We all played better than we ever knew we could.” The circle of heads nodded vigorously. “And as for you, you were fuckin’ amazing on that synthesizer, pardon my French. Jeez, we need you in the band now. Don’t we, guys?” More nods. “You will join us, won’t you...?”

But Aurora’s eyes were flickering shut again.

“I never even got to tell her about the manager of Yes being in the audience, and wanting to book us as support band on their next tour,” complained Ginge.

* * * *

There was nothing wrong with Aurora, the doctor told Lefty when he collected her from the hospital two days later, apart from the life she had been leading. Nothing that rest, good food and vitamins couldn’t fix.

She was installed in her own room in part of what had been Synth’s flat. Ginge and Lefty had moved into the rest of it, since it was so much better than their previous places.

There they were all able to work out new numbers. It was almost always Aurora who took the lead in their compositions; but they quickly discovered that she found it almost impossible to play the same piece twice. This hardly seemed to matter, though, and instead they evolved a sort of code by which they knew what type of number they would play next, whether fast, slow, happy, plaintive, heavy rock, vocal or instrumental.

They also found that, while they all enjoyed playing together and almost every piece proved an emotional experience of some kind, they never reached in practice the heights they had in the Grotto Club. Even so, they deliberately avoided any further public appearances. They wanted to save themselves for the tour with Yes.

Two weeks before the first scheduled gig of the tour, in London, Herbie rushed into the flat, obviously highly excited.

“I’ve fixed it! A whole day in the UROK Studios! The way we’ve been playing lately, we should be able to record a whole album, no problem, and pick the best two tracks for our single. We can have the single into the shops while the tour’s still on—and just watch it go up the charts!”

Days later Aurora found herself being pushed out of a battered, psychedelically painted minibus and helping to carry boxes, amplifiers, and guitar-cases through an ordinary-looking green door, past the dusty and flyblown window of a small office from which an elderly uniformed man peered at them suspiciously, and down a long corridor lined with doors. Through another door and down some rickety wooden steps into a litter-strewn open courtyard between high buildings; up more steps into what looked like the warehouse it had once been.

The inside of the warehouse was a revelation, though. Emerging from a short corridor, Aurora found herself surrounded by glass booths, some containing stand microphones, others chairs and music stands. Fluorescent tubes hung from the high ceiling, while thick black electrical cables snaked in all directions across the wooden boarded floor, on which stood several huge speaker cabinets. In a gallery right across one end of the room, with a metal stairway leading up to it, were more glass windows, behind which brightly lit figures moved about.

The band, with other helpers and hangers-on, rapidly set up their equipment. Aurora noticed that the drum kit was placed in a booth of its own, and saw Doug fitting a pair of headphones over his bushy hair. When she found that she was expected to do the same, she became agitated.

“No!” she cried. “If I can’t have everyone with me, I don’t play.”

The studio engineers tried hard to get her to change her mind, but she was adamant. So the rest of the band were clustered around the synthesizer, microphones were rearranged, and, after the usual twangs and toots of tuning up, the recording session began for real.

The first number lasted twenty minutes. Although as soon as she began playing Aurora fell into her trancelike state, she did see one of the figures in the control booth pick up a telephone several times. Shortly afterwards, people began to file silently into the studio. All but a couple of red lights in the actual studio were dimmed, leaving the control room a bright oasis.

The second piece was also over fifteen minutes long and, when it finished, after a respectful silence of a few seconds in deference to the tape machines, spontaneous applause broke out.

A tinny voice spoke from nowhere. “Far out! We don’t even need any overdubs. But you’ll have to do some shorter numbers—three, four minutes, five max—if you want to put out a single.” Aurora saw that one of the men behind the long control panel in the glasshouse was speaking into a microphone with a long flexible neck. It looked like a goose, she thought.

“Let’s do the vocal?” suggested Ginge, hopefully. He had written the lyric, and was rather proud of it. Another batch of onlookers surged through the door while the red RECORDING light was out.

“OK, the vocal. Then The Seagull—and let’s keep it short,” said Herbie.

Lefty sang the lead vocal; he had a good blues voice, hoarse yet tuneful. Doug, with a mike slung over his drums, joined in the chorus line. To everyone’s surprise, for she had never done this before, Aurora pulled over a nearby live microphone and began to sing, wordlessly. Or was she singing in some foreign language? It didn’t seem to matter. Her voice, while not strong, was pure and clear. She sang a strange harmony to the middle-eight bars, playing the melody line on single, gliding notes. The result was ethereal.

Once again there was wild applause at the end, and it was obvious from comments she heard that these studios had never witnessed such scenes before. Or such music. The effort was taking its toll, but Aurora couldn’t recall ever feeling so happy.

At the close of the next piece, though, Lefty looked concerned, for she was white and strained. “Can we call it a day?” he asked the control room.

The recording engineers were bemused. The Gas Giants had been in the studio for less than two hours. Yet there was certainly enough material in the can for an album, and for the A and B sides of a single. A double-sided number one single, too, or they’d trade in their headphones for brooms and go street-sweeping, as one engineer put it.

From the crowd came cries of “No, more—more!” and “Keep it going while it’s hot!”

Lefty scowled at them and pointed to Aurora. “Look at her, can’t you? She’s about all in.”

He unplugged his bass and put it into its battered case. This signaled the rest of the group to follow his lead. Aurora revived enough to help a little, though she still looked shaken.

She spoke once. “Thanks, Lefty. You’re a real rock.”

When they had left, the studio seemed even emptier than usual. Little groups of people stood around aimlessly for a while, discussing what they had just heard and the rosy future of the band, then drifted away.

* * * *

“Ladies and Gentlemen.... Guys and Gals.... Let’s have a big hand for...the Gas Giants!”

The curtains rolled back and there was a scatter of clapping as sound began to fill the auditorium. Most of the audience had never heard of the band. It was only the support group, after all. The bar remained full to bursting. Latecomers straggled in and stumbled along the rows of seats, forcing grumbling sitters to stand.

The stage was bathed in ripples of violet, blue, green, yellow light which changed and pulsed with the music. Herbie had proved to have no mean talent with electronics now that Synth no longer monopolized the equipment, and his second guitar seemed no longer needed. He operated a kind of keyboard which produced changes of light instead of sound. The band had broken with the convention of patched jeans and T-shirts, and all wore close-fitting black, including Aurora; though her costume was more in the nature of a cat-suit, against which her bright hair shone.

The audience hardly noticed. At first this was because they were talking among themselves, as they normally did during support acts. But very shortly there was a chorus of “Ssshhhh!” and the late arrivals started getting angry glares. In no time the listeners were being carried away on wave after wave of soaring sound, lifting every one of them out of their humdrum, everyday existence, making them forget troubles, ills, quarrels petty or serious, and at the same time welding them into one great corporate entity which was part of the music.

There were no separate pieces of music or songs this time, nor need for applause. For the two thousand people in the theater, each in his or her own way, gave back as much as they received. But the music changed and flowed, so that at times everyone present was silent and sad, at others joyous, bright-eyed. Management, usherettes and bouncers stood at the sides, relaxed; for, despite the electric, emotion-charged atmosphere, there was no hint of rowdiness. A BBC television crew, setting up cameras for the headline group, hastily started filming.

Not everyone agreed on what happened next. To some, it remained a really great concert, the best music they had ever heard, with an unusually good rapport between musicians and audience. And even those who saw the “visions” did not all agree on what they saw. But to most of the latter:

The music was a mighty silver waterfall, leaping and cascading down, down, amongst the crags of a tall volcanic mountain whose peak was lost in the clouds. It crashed, it rushed, it roared, and then it split into myriad streams which splashed, gurgled, tinkled between moss-covered rocks.

The stream which was the music entered a dark cave, where it flowed in echoing darkness for a while, then light reappeared, emanating from globular shapes—fungi?—on the walls of the cavern: blue, green, purple. As the light brightened, the rivulet widened and figures became visible, bathing naked in the now-warm water. Other tributaries swirled in, half-seen through wisps of steam, from gullies among the rocks. Strange, fern-like plants sprang from the banks.

In a sudden glare of sound the torrent sluiced straight down a hillside in the full light of day; yet this daylight had an unearthly quality. The stream broadened, and meandered through open countryside. Trees lined its banks, trailing yellow-green leaves in its swirling surface. On the left, the land rose to a huge, flat-topped hill. Many white-robed people were making their way up its slopes. Among them ran nude and bronzed pale-eyed children, youths and girls, laughing and dancing. The music seemed to swell as though joined by an orchestra and choir from outside itself, rolling down from the rim of the hill....

The people in the auditorium blinked, collectively, as the music seemed to falter. The scene blurred. There were low metal buildings, an interminable flat expanse of sand. Some of the audience felt they were being carried in strong arms. Then the view tilted upward, up over curved metal plates.

Confusion.

Noise.

Pressure.

Red darkness.

Black darkness.

For a long time, total lack of sensation.

Sudden shock, pain. A surge of movement, forward; then falling. Somewhere far off, as though seen through crystal, violent blasts of light: red, yellow, white, red again. Darkness. Falling, falling. Gentle hands lifting, lowering. A jolt, a hard surface below.

Noise!

Fear!

There was a startling crackle and a shower of sparks, and the music stopped abruptly. Aurora reeled back from her instrument, fell into the drums and was caught by Doug, as limp as though she were a rag doll. The curtains were hurriedly lowered. There was a cursory announcement that someone had been taken ill.

After a long and uneasy pause the main band came on and played their usual set. It was one of their best performances, but they played to an apathetic and unresponsive house.

Next day the critics in the musical and national press virtually ignored them. They wrote of the incredibly talented debut performance of this unknown support group, and of the unfortunate collapse of their beautiful young female keyboards player (whose age was given as 16). A few mentioned the almost psychical effect upon the audience; others, practical men and women at heart, wrote of the effective pre-recorded orchestral and choral tapes which had augmented the live performance, and of what must surely be a breakthrough in back-projection, suggesting a new holographic laser process producing lifelike and three-dimensional moving images of scenes and people.

The rest of the Gas Giants’ tour had to be cancelled, of course, but, thanks to all the publicity, both the single and the LP, rush-released within the week, were immediate hits, remaining in the charts for months. Even so, everyone who had been present at the concert—or at the recording studio, or at the Grotto Club—agreed that, fine though the records were, they failed to capture the intensely personal atmosphere of the live performances. Something indefinable was missing.

Aurora was missing, too. The Gas Giants brought in Herbie’s younger sister, her hair bleached blonde, and mimed to their tapes on Top of the Pops. But without Aurora they seemed like insensate marionettes.

A few months later, they dissolved the band.

* * * *

Lefty often relived that night in his dreams. He saw Aurora reach into the electronics-filled innards of the synthesizer, seeking...seeking what? Some new sound? Who knew?

He had shouted uselessly: “Aurora—DON’T!”

The shock from the full mains voltage had sent her flying backwards. As Doug had carried her inert body into the dressing room, he’d known for sure she was dead.

But she wasn’t. After they had loosened her clothes and, in lieu of brandy, poured a measure of scotch from Ginge’s hipflask down her throat, she had revived quickly, and sat up. It seemed to Lefty that something had gone from her face. As she changed into her street clothes and walked to the door her expression was blank, reminding him of the first time he had seen her.

Little girl lost.

“Where do you think you’re going?” he asked.

“Back up to Inverness, perhaps. I think maybe I’ll study for a while; try to get into university. I’m wasting my time here.”

“Wasting your time? But what about the band! We’re gonna make it big, can’t you dig that? You can’t just walk out on the rock scene now, just like that.”

“Rock?” she said. A faraway look flickered in her eyes and then was gone. “Oh, yes, rock,” she’d said coldly as she’d closed the door behind her. “That’s all that matters, isn’t it?

“Rock....”