Читать книгу Candymaking in Canada - David Carr - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1 Letter From the Candy Counter

Оглавление“Chocolate is a perfect food, as wholesome as it is delicious, a beneficent restorer of exhausted power . . . it is the best friend of those engaged in literary pursuits.”

Baron Justus von Liebig

Selecting a snack treat is not what it used to be. At the corner store, chocolate and candy are two islands in a sea of tempting alternatives that has expanded from potato chips and ice cream to include individual packages of cookies and crackers.

The total candy market in Canada, including chocolate bars, boxed chocolates, cough drops, candied breath mints, and non-chocolate confections, is 2.3 billion. And what do we get in return for our money?

Chocolate continues to dominate the candy counter, with close to 50 percent of the market. The bulk of those sales have been described by one European-based chocolate society as a “low-grade, cloying confection.” The difference between low-grade and high-grade chocolate is the amount of cocoa butter introduced into the recipe. The higher the butter count, the better the chocolate. Or so say the experts.

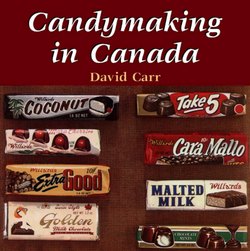

Neilson’s dominated the candy counter, as this photograph shows. Still, there are packaging examples of other products, including Rolo, Biscrisp, Caramilk, Aero, Sweet Marie, Caravan, Kit Kat, Coffee Crisp, Smarties, Raisins, Milky Way, and Turkish Delight.

Most Canadians appear to think differently. Last year, on average, we gobbled up approximately twenty-five pounds of chocolate. Kit Kat remains the perennial favourite, with Coffee Crisp, Oh Henry, Smarties, Caramilk, Reese Peanut Butter Cups, Aero, the original Mars bar, Wunder Bar, and Mr. Big routinely rounding out the top ten. Interestingly, Snickers, which usually finishes in the top three in the United States, ranked eleventh in Canada at last count.

Also of interest is the fact that only one in ten chocolate bars lasts for very long in the marketplace. Five of the bars on that list have been around since before the Second World War—all but two since the 1960s.

Manufacturers have been trying to improve the odds of new products by putting a new twist on favourite brands, either permanently or as so-called special editions. Hence chunky Kit Kat and Aero, and the addition of orange flavouring in bars such as Coffee Crisp and Crunchie (whose parent, Cadbury, owns Crush brand soft drinks). The trend has continued into the freezer, where we can routinely purchase ice cream versions of our favourite chocolate treats.

Meanwhile, Canada’s taste in chocolate is changing, as more Canadians are willing to either put to one side or complement our traditional preference for milk chocolate in favour of darker varieties.

John Lebel, an assistant professor of marketing at Concordia University’s John Molson School of Business, attributes this first change in twenty years to Michel Montignac, a French physician who, like his seventeenth-century predecessor, is trying to promote the healthier aspects of dark chocolate—at least where comparisons are concerned. (Of course, Dr. Montignac has his own line of dark chocolate, so his motives can be questioned, even if the success of his message cannot.)

Preferences in chocolate, as well as in candy, were once strongly defined by regional tastes. In Quebec, the sweeter the better. Smiles and Chuckles’ Turkish Delight would fly off the shelves in Newfoundland, though not in other parts of Canada. Today, 80 percent of candy is universal within the Canadian market.

But regional differences in taste still remain. French Canadians are more adventurous and have created a vibrant new market for traditional recipes like dark chocolate mixed with green peppercorns. Chocolate lovers from Quebec are also more interested in matching chocolate with wine.

Even with such regional exceptions, variations in taste now travel along age and gender rather than geographic lines. How so? Males account for no more than 35 percent of chocolate consumption. At least we’ve moved male consumption out of the closet. Take, for example, an article about The Demon Candy that appeared in the September 1910 issue of The Atlantic Monthly, describing men as secretive chocolate consumers:

It was probably true that children and females consumed the bulk of [chocolate], although secret candy-eating may even at that time have been in its incipiency among the fathers of a generation that still consumes its confectionery with a certain unpleasant reticence.

It was Jean Harlow, not John Barrymore, who bit into a piece of chocolate in the 1933 comedy classic Dinner at Eight, thus showcasing the simple indulgence on the silver screen for the first time. Harlow was probably enjoying a piece of milk chocolate. “Women tend to prefer milk chocolate,” says Leber. “However, as they age, they begin to acquire a taste for darker chocolate.”

Boxed chocolates continue to be popular, although the market has altered significantly. Young men no longer feel the pressure to impress (some would say bribe) the mother by arriving at the door with a fancy selection when taking out the daughter for the first time.

Today, the biggest boxed chocolate occasions are Valentine’s Day, Easter, and Mother’s Day. These three account for 80 percent of boxed chocolate sales (though the major grocery store down the street sells a whopping 70 percent of its chocolate boxes just at Christmas). The rest of the year, manufacturers “eat their profits,” says Lebel.

One part of the chocolate industry unlikely to change remains our resistance to low-fat varieties, as evidenced by the short-lived Crispy Crunch Light. It would appear that once we have decided upon a treat, we have already crossed the calorie threshold. A chocolate bar with 33 percent less fat is not going to make a difference. Why should it? Although with recent obesity red flags and the noticeable switch to dark chocolate, the day may come when it does.

What is certain on both sides of the candy counter is that while our appetite for confections continues to grow, the number of companies feeding that hunger will continue to shrink. In 1961, Canada had 194 plants in production. Today, we have fewer than 94. The major cause has been consolidation and the phasing out of smaller, obsolete production facilities. Some of those that have melted away were once located in the heart of major Canadian cities, housing operations in magnificent turn-of-the-twentieth-century brick factories.

The convergence of chocolate and non-chocolate brands has also contributed to the sunset. Sugar is popular again, and this time chocolate manufacturers are refusing to sit on the sidelines as Canadians flock to candy counters and recently opened candy stores to fill up on their favourite chocolates, sweets, and bags of nostalgic treats.

Canada’s confectionery industry is anxious to cash in on the fastest growing segment of the confections business, changing the complexion of what was once a market dominated by faceless, independent suppliers of bubble gum, sours, and jellies (categories that the over thirty-five demographic may refer to as penny candy).

“It still is penny candy, but these days it’s a penny a gram instead of a piece,” jokes Jack Green, president of Toronto-based Retail Entertainment Inc., which owns Suckers, an interactive candy store that blends a wall of bulk confectionery bins with packaged brands and candy-related toys, music, and videos.

In an average week, Canadians drop as much as 600 million pennies (60,000) at high volume candy stores. Other candy stores eschew the glitz of Suckers for a basic retail concept more reminiscent of the old-fashioned candy store.

Whether consumers go for high energy or stark wooden floors—or the candy counter at the corner store—it is the shelves that tell the story. And more shelf space is being handed over to branded sugar products.

“The competitive set is changing in the market,” explains Paul Sullivan, vice-president of marketing for Cadbury Trebor Allan, a recent merger between Britain’s Cadbury chocolate maker with Burlington, Ontario’s Allan, Canada’s largest supplier of five- to twenty-five-cent candy pieces (the so-called chunk or count goods segment). “Major branded players from chocolate are moving into the sugar side of the business and are bringing some of their branding techniques over.”

Cadbury, which bought William Neilson Ltd., maker of domestic favourites such as Jersey Milk, Crispy Crunch, and Sweet Marie, is not alone. Other chocolate makers have moved into the sugar candy business, including American-based behemoths Mars (Skittles) and Hershey (hard-boiled candies and caramels), as well as Nestlé Canada, the Canadian subsidiary of Nestlé S.A., the global food giant based in Vevey, Switzerland, which also produces Kit Kat, Smarties, and Canada’s own Coffee Crisp.

Nestlé purchased London, Ontario-based O’Pee Chee in 1997, rolling several licensed favourites like Sweet Tarts, Nerds, and purple Thrills chewing gum under its American Wonka brand.

“There is an increase in strong branding in the business,” says a spokesperson for the Nestlé Wonka brand. “We’re branding fun, and we’re relying on established brands such as Nerds to capitalize on new trends.” This includes a new line of Wonka gumballs with Nerds tucked inside.

It is a matter of growth potential, according to Cadbury Trebor Allan’s Paul Sullivan. The sugar segment is exploding like Pop Rocks (a popular kid’s confection that bursts inside the mouth). “Categories are harder to define in Canada, but you look at trends in the U.S. over the last five years and sugar has been growing at between eight and nine percent a year, while chocolate sales are flat.”

Plus using sugar offers more to work with in terms of colours and shapes that appeal to the fickle core market of six- to nine-year-olds. Paul Cherrie, vice-president of Concord Confections agrees. “The price of entry used to be that the candy had to taste good. Now the candy has to actually do something.”

Named after the southern Ontario region where it is based, Concord Confections bills itself as the world’s largest manufacturer of gumballs. The company made North American headlines in 1990 when it purchased New York-based Fleer Confections from the financially troubled Marvel Entertainment Group, publisher of Spiderman comics. Fleer accidentally stumbled on the recipe for Dubble Bubble, the world’s first bubble gum, in 1928.

“Until Dubble Bubble we didn’t have a recognizable brand,” admits Cherrie. “We had to scratch and claw our way into the market. We now have a trademark that took generations to build. Dubble Bubble is to bubble gum what Coca Cola is to soft drinks.”

And is that important in a market that caters to the most fickle of all tastes?

Approximately 95 percent of Concord’s market is in the United States. Interactive brands include Candy Blox, stackable sugar bricks with a taste similar to Wonka’s Sweet Tarts. “If you place Candy Blox against Sweet Tarts, a kid is going to go for the Blox because of the play value,” Cherrie says. And not just kids: several years ago, a Chicago architectural firm placed the single largest order for Candy Blox to present a sugar-based model of a building for a client. Sort of a Lego set that should be kept out of the rain.

Another attraction of sugar has been the low-cost approach to marketing. Pez, one of the original interactive candies, has never engaged in marketing since the company first introduced plastic dispensers to sell coloured candy bricks in the 1950s. Pez remains one of the industry’s top sellers. “Sugar candy has been around forever and candy stores have been around forever,” says Sean McCann, president of Sugar Mountain, another candy store chain with outlets in Toronto and Vancouver. “It’s the candy that sells.” Still, there are signs that this too is changing.

An estimated 250 new sugar products appear on store shelves every year. And recipes seem to call for more: more sour, more colourful, more interactive. More than 90 percent of the new entrants will disappear within two years. Novelty candies and candies linked to popular culture will dissolve even faster.

“There’s always a risk with products tied to a movie or other piece of popular culture,” a marketing representative at Topps points out. “But it can deliver a big bang if timed right.” To reduce the risk, manufacturers such as Cadbury Trebor Allan will use licensees for promotional work as opposed to launching new products.

Cadbury Trebor Allan has used hockey legend Wayne Gretzky and basketball great Shaquille O’Neal to promote Mr. Big. More recently, the company used Toronto Raptors star Vince Carter to act as a spokesman for several brands in Canada and the United States, where the company sells approximately 40 percent of its candy.

There are also signs that Canada’s sugar candy industry is taking marketing to the next level, which will include radio and television spots.

Werther’s Original butterscotch drops was one of the first sugar confections to realize the potential of television. “Almost overnight they turned the candy into a huge brand with a big following,” says Sullivan. “Television is the next step. In the U.S. most of the major companies have sugar confectionery advertising on TV.”

And what are Canada’s sugar candymakers likely to push? Suckers are enormous, according to Topps. That category has been redefined by the return of the Chupa Chup.

While kids will continue to drive the sale of sugar candy, the size of the retro market cannot be dismissed, although most candymakers insist it is the by-product of a healthy industry. “We don’t target nostalgia,” Nestlé’s insists.

Concord’s Paul Cherrie argues that as an overarching trend, the retro market will fade, but that should not hurt manufacturers with established brands. “Confectionery really is a category that transcends age barriers. Our core market does not remember what retro is.”