Читать книгу Invading America - David Childs - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 3

The Charters: Come Over and Help Yourselves

There stood a man of Macedonia, and prayed him, saying, Come over into Macedonia, and help us.

Acts 16: 9, King James Bible, 1611

Come over and help us.

Motto of Massachusetts Bay Company, 1629

In an age of centralized authority, few Englishmen dared venture abroad without royal approval. This meant that each of the fingers thrust towards America wore upon them a signet ring in the form of a royal letters patent, or Charter (listed in Appendix 2). The exception to this was Frobisher’s thumb, to whose ‘Company of Cathay’ the canny Queen Elizabeth, refused to give her seal of approval having lost her original investment of £1,000 in Frobisher’s gold prospecting voyages. She was not to repeat that mistake. Henceforward she would always choose the cheapest option, passing off her parsimony as prudence. The publication of royal Charters would ensure that she, and succeeding monarchs, could claim a copyright without investing cash.

So, for a Crown that wished to control but not command, to create but not contribute, a concessionary awarding Charter leading to the creation of a colonial commonwealth was a very clever concept. Through the issue of such documents the monarch could claim rights and rewards without responsibilities, and authority without administration: an arrangement that demanded influence without commensurate investment. So England instilled at the start of its American adventure a system and a relationship whose final logical outcome would be a revolution proclaiming ‘no taxation without representation’. There was another advantage that the Charter system had for its investors – it created a closed market. This was the age of monopolies, the purchase of which guaranteed both the seller, the sovereign, and the selected purchaser a rich return for no investment. It was not until 1624 that Parliament, manned by men of property, felt able to challenge the Crown by declaring monopolies were contrary to the fundamental laws of the land. King Charles ignored their strictures. Thus the produce of America was perceived as being beneficial to existing monopolies, such as glass, soap and silk, as well as creating new ones such as tobacco, sassafras and beaver fur.

As the century developed, and as the concept of a commonwealth matured, successive rulers introduced their own ideas as to how best to manage their overseas infants. Thus Henry VII was content to let a foreign national work speculatively for England’s cause. Elizabeth, an admirer and user of favourites, felt her newfound lands were best when, in Donne’s words, they were ‘by one man manned’, which meant Walter Ralegh. James I, who liked not Ralegh and whose own intimate ‘sweethearts’, Somerset and Buckingham, were not interested in overseas, began by appointing committees over whom, as his confidence waxed and their capabilities waned, he exercised gradually more management until, in 1624, the Crown took direct control of Virginia while still awarding blocks of land to a coterie.

Whoever the beneficiary, the Charter process can be summed up along the lines proposed by Francis Jennings:

1. The Crown was petitioned to lay claim to territories previously outside its jurisdiction and over which it had no true legal claim.

2. The Crown authorized a person or organized group by charter to conquer the claimed territory and to exercise a monopoly over its trade.

3. The successful conqueror became the possessor and governor of the territory, subject to the terms of the charter and the continuing acknowledgement of the sovereign’s overlordship.

4. The charter holder was authorized to encourage settlement through the issues of land, mineral and fishing rights and to raise capital through the issue of shares, estates or lottery tickets to sponsors.

5. The Crown would be a beneficiary but not an investor.

If the state was going to risk little then it had, paradoxically, an interest in offering the grantee much for two very valid reasons. The first was that, having laid claim to these lands, the Crown wished to exclude any other state from either counter-claiming or muscling in on these new domains. The Charters were thus being used like balloons inserted flaccid through a small hole into a large vacuum and then blown up to fill all the space available, providing a thin but taut membrane which, if penetrated, would cause a loud explosion. No matter that the empty space was filled largely with air, it was the boundary rather than what it contained that was important. The second reason was that, by offering much, the Crown hoped that its gift would contain enough, albeit thinly spread, to produce a reasonable return. What the state never comprehended was just how vast America was and how great would be the resources necessary to tame it.

In 1496 Henry VII’s Charter implied that Cabot and his crew were capable of seizing and occupying a land which, by its very description, as having towns and cities, was settled by a civilized people. In response to the King’s horizon-stretching largesse, John Day reported to Spain that Cabot, after he landed in America, ‘Since he was with just a few people . . . did not dare advance inland beyond the shooting distance of a cross-bow’, which was hardly the action of a potential conquistador or even major explorer.

By the time Elizabeth was persuaded to award her first colonial Charters, the government concept of what such grants involved had matured. Thus the letters patent granted to Sir Humphrey Gilbert, his heirs and assignees in 1578 gave him very similar benefits to those awarded to Cabot, but added permission ‘to build and fortify’ and additional rights for those who came after ‘in a second voyage of conquest’. This document also introduced: a geographical boundary and a timeframe, stating that Sir Humphrey’s jurisdiction would cover those who ‘abide within two hundred leagues of any said place where the said Sir Humphrey . . . shall inhabit within six years next ensuing the date hereof’, and a legal control in requiring that the Secretary, Lord Treasurer and Privy Council be involved in the licensing of the resupply of any settlements. There is also a mention of the paying of duty and other taxes on any gold or silver ore that might be discovered, an acknowledgement of the success the Spanish had had in discovering such wealth, ignoring Frobisher’s constant failure to do likewise.

The geographical boundaries and timeframe for establishing a settlement were obviously felt to be sound, for they remained in the Charter that Elizabeth granted to Sir Walter Ralegh in 1584, which was a redrafting of the Gilbert original, so that it could be rescued from the watery grave that was the unlucky Gilbert’s lot and presented to a man who was both a relative of Gilbert and the Queen’s current favourite. So beloved was he that, unlike either Cabot or Gilbert, his half-brother, Ralegh was not allowed to travel across the ocean in person. This seemingly capricious decision by the enamoured Queen established yet another pattern in the Charters, whereby the investors stayed in England and encouraged others to risk their all on their behalf. This would necessitate the appointment of a leader or governor, who might hold neither the rank nor the relationship with the sponsor to demand undisputed authority over those over whom they had been placed in command in these isolated, strange and dangerous lands. The fatal flaw thus soon emerged; where harmony was essential discord would develop.

Ralegh’s demesne was created to include the shoreline settlements stretching six hundred miles both north and south from the first township he intended to build called, modestly, the City of Ralegh. To encourage wealthy sponsors he offered, the second time around, county-size estates to all who backed his scheme, selling some 8.5 million acres of these in Virginia. Sir Philip Sidney acquired 3 million acres, giving him title to an estate that was as large as the combined area of Devon and Cornwall and half of Somerset. To give just two more comparisons: the National Trust in England and Wales, owns some 550,000 acres, while the Crown estates measure just 384,000 acres. Ralegh and his friends were rewarding themselves with empires hewn from other men’s lands by other men’s efforts. Neither were monopolies on the extractive industries neglected: Sir Thomas Gerard was promised two-fifths of the profit from all the gold, silver, pearl and precious stones extracted from the settlement, which gave him, as it turned out, two-fifths of nothing to increase his fortune. This proposed greedy land grab again illustrates that the English were planning, badly, an invasion of Virginia. Estates of the size being offered covered lands already occupied by native peoples; the English could only claim them as their own by seizing these peoples’ land and imposing their own land grant laws above that of the traditional authority.

For Ralegh, the requirement to have established settlements within six years of his Charter being granted must have seemed at the time just a legal technicality until, after Lane’s colony withdrew in 1586 and White’s was finally reported missing in 1590, it looked as if its term was ending. Desperate to retain his generous award, Ralegh needed to prove both that he had settlers alive in America and that he would confront any who tried to flout his authority. Thus, in 1602, he not only had Samuel Mace seek to make contact with the lost colonists but also wrote a note to Sir Robert Cecil, demanding that the cargo of sassafras landed from the returning Concord, following the voyage to North Virginia by Bartholomew Gilbert and Bartholomew Gosnold that same year, be impounded as infringing his monopoly. Then, realizing that he might be on shaky ground, he used his justly famous silver-tongued flattery to persuade John Brereton, who wrote the account of the Gosnold voyage, to dedicate his book to him and to include a note which stated, erroneously, that the voyage had been made ‘by the permission of the honourable knight, Sir Walter Ralegh’ – a tacit reminder of Ralegh’s suzerainty.

This was Ralegh’s last effort to retain his Charter rights. In March 1603 his Queen was dead. In July he was placed in the Tower to answer charges of treason. In November he was tried and sentenced to death. Only King James’s cunning clemency granted him a stay of execution long enough to have him embroiled in a voyage to Guiana in 1617, the failure of which would finally lead him to the block. Among those who passed judgment at his first trial were Sir Robert Cecil, Sir John Popham, the Lord Chief Justice, and Sir Edward Coke, the Attorney General. A cynic might see some link in the fact that it is their names which are associated with the drafting of the first Charter for Virginia in April 1606, at a time when Ralegh had been in the Tower long enough to be either no longer a disruptive force or a man with any public following. Nevertheless, his shadow fell on the deliberations, for, among the eight suitors to be named in the Charter were Raleigh Gilbert and William Parker, respectively a relative and a servant of Sir Walter, who it can be presumed were included to avoid any outbreak of unpleasantness.

The continuing issue of Charters so early in James’s reign is a cause for some surprise since the King’s major foreign policy was to secure peace with Spain and not to go to war again. Yet he was content not only to sign a potentially contentious document but also to remain resolute in the face of Spanish objections. One reason for his support of this new venture was that, in the years since Ralegh’s failure at Roanoke, many English merchants and speculators had learned more about the potential opportunities that America might offer. In the north, fishing, furs and forestry seemed available for exploitation, while in the south the climate could encourage the planting of crops traditionally imported from the Mediterranean, as well as offering a chance to increase the acreage the nation had devoted to industrial crops such as flax and hemp and silk, a special favourite of the King. Thus began a fault line between an extractive north and an agricultural south, which would be emphasized in the Charter of 1606 and finally shear into the earthquake of 1861. Back in 1606, however, what investors hoped to find within this landscape was mineral wealth and a navigable route to ‘nearby’ Cathay.

In England, the north–south divide of Virginia was reflected in an east–west divide of investors in the first Charter for Virginia, with West Country merchants of Bristol, Plymouth and Exeter being granted the right to settle and exploit the land lying between 38º and 45º North, that is from Chesapeake Bay to present-day Bangor, Maine, while London businessmen were offered the bloc between 34º and 41º North, from Cape Fear to Manhattan Island. The obvious overlap seems to have been inserted to encourage competition and expansion, but even within their exclusive boundaries the two companies established to manage the colonies were only given control of a square of territory stretching fifty miles either side of any settlement and a hundred miles inland, as well as the adjoining seas out to the same distance.

The two colonies thus created were to be organized by two separate companies that would be overseen by a royal council of thirteen members appointed by the King and named the Council for Virginia, which would include four representatives of both sub-groups.

The Charter named eight individual suitors; four West Countrymen for the northern plantation and four Londoners for the southern one. Their names and backgrounds are indicative of the purpose and development of the nascent colonies. The link with the jailed Ralegh remains even here, and there can be little doubt that the noxious Wade was present to act as a spy on the ‘shepherd of the sea’ now locked up ashore.

Suitors for Licence to Establish a Colony in Virginia, 1606

Excluded by name are the ‘divers others of our loving subjects’, which probably encompassed Sir Robert Cecil, by now Lord Salisbury.

Members of the Council for Virginia

Unlike Ralegh before them, many of these investors did risk their own lives to gain their reward. Of the eight grantees named in the 1606 Charter of Virginia, Sir Thomas Gates, Sir George Somers and Edward-Maria Wingfield sailed to Jamestown, while Raleigh Gilbert and George Popham established the short-lived northern colony. Later, in 1628, George Calvert tried to settle in Newfoundland, where he had been granted extensive charter lands. Thus there was an attempt to lead by example and endure with equanimity the hardships that those they had almost conned into taking passage had to face with uncertain support from their backers. Their misfortune was that they were, for the most part, not able to command that which they had created.

The Jacobean Charters continued the tradition of awarding a generous grant of resources, which, of course, were not the king’s to give, allowing the settlers to ‘have all the lands, woods, soil, grounds, havens, ports, rivers, mines, minerals, woods, waters, marshes, fishings, commodities, and hereditaments, whatsoever, from the said place of their first plantation . . .’

Among the minerals expressly mentioned, copper, after it was reported as being much used by the native Amerindians, joined gold and silver as being one of the minerals for whose extraction the Crown required a percentage payment. The overwhelming desire for gold was nowhere more evident than in the change of plan for Frobisher’s northern voyages, for no sooner had he returned from his first expedition in 1576 with a lump of black rock, than the search for a route to Cathay was abandoned in favour of gathering vast quantities of this worthless stone. The resulting attempt to establish a settlement near Baffin Island in 1578 might have been doomed, but the 100 people who were selected to form this early English colony in the new world were wisely chosen as far as their trade was concerned. They included forty seamen, thirty miners and thirty soldiers, all under the command of Edward Fenton. Luckily circumstances enabled them to avoid trying to endure the unendurable – an Arctic winter – but the mix of skills is hard to fault. This was not so in Virginia.

The 1606 first Charter for Virginia had within its framework the seeds for success, which were encouragingly watered by the issue, the following November, of Instructions for Government, which were enforced in December by Orders for the Council for Virginia, which assigned ships and their captains, to whom were issued sealed orders. However, at the same time, the London Council for Virginia issued Instructions Given by way of Advice . . . for the Intended Voyage to Virginia to Be Observed by those Captains and Company which Are Sent at This Present to Plant. This proved to be the inhibitor for the southern group, for it moved away from the simple aim of establishing a successful colony that would export what it was able to glean, to one which was to have, amongst several aims, the requirement for further exploration, specifically to find a way to the ‘Other Sea’, the Pacific Ocean, and to search for gold. It was in choosing to follow rivers that might lead to this mythical route that the colonists lost their way. The error they imported is obvious from the text which, assuming they numbered 120 and not the 104 that disembarked, required forty of them to build the fort and protect the settlement, thirty to clear and plant, ten to man a watchtower at the river entrance and forty to spend two months in exploring the route to the Pacific. In commanding this division the Council failed to appreciate several things: the challenges that the settlers would meet; the priorities that would be imposed by their circumstance; the nature and size of the terrain on which they would disembark and, probably most significant of all, the composition of the force that they would require to secure their beachhead. Records of the known occupation of some 240 of the 295 individuals who arrived in Virginia before October 1608 show that they included, inter alia: 119 gentlemen, forty-seven labourers, fifteen artisans, seven tailors, four carpenters and four surgeons, some ‘boys’, and a cooper, a couple of blacksmiths, brickies and refiners, two apothecaries, a gunsmith, a fishmonger and a fisherman, and several other individual specialists among whom was the most remarkable defensive inadequacy of an army captain, a sergeant, a soldier and a drummer.

Reading the above list of occupations one might interpret it as representing those present at a gentlemen’s club picnic outing to an area where it had been rumoured some unruly behaviour had been reported but where it was still intended to construct a barbecue and spend some time choosing a selection of local valuables to take home as trinkets to pacify absent wives. In fact, as far as Jamestown was concerned, the majority of the gentlemen were a burden in several ways; firstly, they would not labour; secondly, they needed to be fed, and thirdly, they spent time in fractious intrigues that made a mockery of governance.

The contrast with the establishment proposed by the anonymous wellwisher of 1584 for Ralegh’s Roanoke voyage, which laid down the trades necessary to be deployed, is all the more remarkable not only because it was again ignored but also because no lessons had been learned from the failures of 1577, 1578, 1585 and 1587. No one, it seems, drew up a profile of the ideal group necessary for establishing a colony and then sought to recruit the skills indicated. Instead, a disparate collection of motley, unhardened, untested and disunited individuals were dispatched to their doom. Had the Charter, or even the Advice, laid down the trades required and told the leaders to concentrate on establishing a settlement before any other activity, the result might have been less tragic and more successful.

When it became obvious, after a short while, that the northern Virginian enterprise had failed and that the southern one was not going to reward its investors in accordance with their expectations, a second Charter was drawn up, in 1609, by the King ‘at the humble suit and request of sundry of our loving and well-disposed subjects’. If the first Charter failed to deliver mainly through its application rather than its text, the same could not be said of the second, which is one of the most over-optimistic pieces of paper ever penned in that, although it established a far better form of government for the settlers themselves, it created a vast joint-stock company, eager to benefit from the output of the plantation. Although not as stark as a death warrant, it was one of the longest assisted suicide notes in history, killing with kindness and an indigestible surfeit.

The kindness came with the land grant. Whereas the first Charter had granted land within fifty miles either side of the initial settlement and stretching up to a hundred miles inland, the second Charter was far less restrictive, offering the settlers dominion from sea to sea, stating:

we do also of our special Grace . . . give, grant and confirm, unto the said Treasurer and Company, and their Successors . . . all those Lands, Countries, and Territories, situate, lying, and being in that Part of America, called Virginia, from the Point of Land, called Cape or Pointe Comfort all along the sea coast to the northward two hundred miles and from the said Point or Cape Comfort all along the sea coast to the southward two hundred miles; and all that space and circuit of land lying from the sea coast of the precinct aforesaid up unto the land, throughout, from sea to sea, west and northwest; and also all the islands being within one hundred miles along the coast of both seas of the precinct aforesaid.

These boundaries encompassed the lands explored and mapped by John Smith but also kept alive the idea that somewhere in their inner regions lay the much-sought route to the Pacific.

The surfeit was created by the number of individuals and organizations who were encouraged to invest in the enterprise – pages of them. This multitude consisted of 659 individuals and 56 London livery companies as well as a number of the settlers themselves, all of whom invested in a share, or shares, worth £12 10s, or multiples thereof, a not insignificant sum, the attraction of which was partly based on the erroneous report by the returning Captain Newport that gold had been discovered in Virginia. Among those recruited to purchase stock were eight earls, one viscount, one bishop, five lords, seventy-two knights and thirty-nine naval captains, as well as the usual crowd of gentlemen and esquires. Among the guilds were the Grocers, Brewers, Fishmongers, Tallow-Chandlers, Masons, Plumbers, Brownbakers, Carpenters, Haberdashers, Gardeners, Ironmongers and Barber-Surgeons, many of whose members, if they travelled, would have had practical skills to offer the settlers; while some, such as the Company of Goldsmiths, had skills desired but unwarranted. The take-up was oversubscribed for what was on offer and included both the stay-at-homes and adventurers willing to travel towards a better life. Those who chose to venture across to Virginia were offered, for their one share, after seven years’ labour, a grant of land and a share of the profit from ‘such mines and minerals of gold, silver, and other metal or treasure . . . or profits whatsoever which shall be obtained’.

A clear indication that the investors realized, too late, that they were not on to a good thing, can be read in the third Charter of 1611, which stated that the Company had:

power and authority to expulse, disfranchise, and put out from their said Company and Society for ever, all and every such person and persons, as having been promised or subscribed their names to becoming adventurers to the said Plantation, of the said first Colony of Virginia, or having been nominated for Adventures in these or any other of our Letters Patent, or having been otherwise admitted and nominated to be of the said company, have nevertheless either not put in any adventure at all for and towards the said Plantation, or else have refused or neglected, or shall refuse and neglect to bring his or their Adventure, by word or writing, promised within six months after the same shall be so payable and due. And, whereas the failing and nonpayment of such monies as have been promised in Adventure, for the advancement of the said Plantation, hath been often by experience found to be dangerous and prejudicial to the same, and much hindered the progress and proceeding of the said Plantation, and for that it seemeth to us a thing most reasonable, that such persons, as by their hand writing have engaged themselves for the payment of their adventures and after have neglected their faith and promise, should be compelled to make good and keep the same; therefore, our will and pleasure is, that any suit or suits commenced, or to be commenced in any of our Courts of Westminster, or elsewhere, by the said Treasurer and Company, or otherwise against any such persons, that our judges for the time being . . . do favour and further the said suits so far as law and equity will in any wise further and permit.

This was a longwinded way of advertising the fact that the Company was in trouble: it would certainly not have been able to argue its case should a seventeenth-century credit agency have removed its AAA rating, if it had ever warranted one. Michael Lok, the Treasurer of the Cathay Company in 1578, had found himself in a similar position as far as non-payment of promised investment was concerned but, lacking the robust endorsement of his sovereign, it was he and not they who went to prison. The long quotation above serves to illustrate that the Charters were not just a means whereby the Crown gave and granted rights to a ‘suit of divers and sundry loving subjects’ but that they also served as a business prospectus to attract adventurers. For the most part their lengthy verbiage did not lead to long lines of emigrants queuing at the docks or investors’ carriages rolling into the City. Those people that did not go did not ignore a golden opportunity for, by staying away, the probability is that they either, in the case of voyagers, saved their lives, or, in the case of investors, kept their savings. It was, in the modern jargon, a no-brainer.

The first settler groups that had landed at Jamestown had been about the size of a small English village, such as Scrooby in Lincolnshire, from where William Brewster and many of the Pilgrim Father separatists hailed. From the sweat of their brow the households of such villages had to support themselves and, probably, the lord of the manor and his family, and the local priest, while a few artisans, millers, blacksmiths and thatchers provided support either of a fixed or seasonal nature. Thus, in such communities, the majority worked the land and produced a sufficient surplus to feed a few more mouths than were hungrily opened by their own family, for it was an age of both feast and famine. Most of these communities were not entirely self-sufficient. Markets had to be visited to buy some items, while itinerants offered both extra labour when required, and additional skills when desired. Surplus? There was little or none and yet, from Virginia, such a village was meant to reward thousands!

THE CONVERSION OF SOULS

Queen Elizabeth famously stated that, as far as religion was concerned, she did not wish to have a window into men’s souls. She may have well included the ‘heathen’ in this rubric because, despite the emphasis that both Richard Hakluyts placed on the idea that ‘this western discovery will be greatly for the enlargement of the gospel’, such an aim did not feature in her Charters. It was present in those awarded by King James but the emphasis varied over time. Thus in the first Charter of Virginia of 1606, paragraph three stated:

We, greatly commending and graciously accepting of, their desire for the furtherance of such noble work, which may through the providence of Almighty God, glorify his Divine Majesty, in propagating the Christian Religion to such people that live in darkness and miserable ignorance of the knowledge and worship of God, and may in time civilize, the infidels and savages, living in those parts, to live in settled and quiet government . . .

In the lengthy and businesslike Charter of 1609, this requirement was moved to the very end, where it set down: ‘Lastly, because the principal effect which we always desire or expect of this action is the conversion and reduction of the native people to the worship of God and the Christianity . . . we should be loathe that any person should be permitted to pass that we suspected to affect the superstitions of the Church of Rome . . .’

Of the two aims it was probably the latter to which the King held most dear. Having managed to wind two threads together, James did likewise in the 1620 Charter of New England, in which he linked the abandonment of the land by the native population (in fact due to the ravages of imported disease) to the need for their conversion:

those large and bountiful regions, deserted by their natural inhabitants, should be possessed and enjoyed by such of our subjects and people who . . . are directed hither . . . that we may boldly go to the settling of so hopeful a work which will lead to the reduction and conversion of such savages as remain wandering in desolation and distress, to civilization.

By the time that Charles I awarded a royal patent to the Massachusetts Bay Company, in 1629, the proselytizing mission had been amended. No longer was there to be a mission of conversion but the guiding text, at least within the Charter, seems to have been Matthew 5:16. ‘Let your light so shine before men that they may see your good works and glorify your Father which is in heaven.’ This was transliterated into the Charter in the form: ‘whereby our people inhabiting there, may be so religiously, peaceably, and civilly governed, as their good life and orderly conversation, may win and encourage the natives to the knowledge and obedience of the one true God and saviour of Mankind and the Christian faith . . .’

This was the Company whose very seal depicted a naked savage imploring, in the words of Saint Paul’s Macedonian, ‘Come over and Help us.’ The Christians who answered that call came over and helped themselves, aided by the grants graciously bestowed upon them by their sovereign. What the ‘natives of the country’ received were bullets rather than Bibles.

The Virginia Company made sure that, as far as its public face was concerned, it behaved in a way appropriate to the royal wishes and so it was careful to issue with its propaganda an argument to persuade the morally squeamish that the settlements could only improve the lot of the natives from whom no land would be taken unfairly. To this end it commissioned the Reverend Robert Gray to write a book entitled A Good Speed to Virginia, which was published on 28 April 1609, just a month before the Charter was issued, and which assured its readers that, although:

The report goeth, that in Virginia the people are savage and incredibly rude, they worship the devil, offer their young children in sacrifice unto him, wander up and down like beasts, and in manners and conditions, differ very little from beasts, having no Art, nor science, nor trade, to employ themselves, or give themselves unto, yet by nature loving and, gentle, and desirous to embrace a better condition. Oh how happy were that man which could reduce this people from brutishness, to civility, to religion, to Christianity, to the saving of their souls: happy is that man and blest of God, whom God hath endued, either with means or will to attempt this business, but far be it from the nature of the English, to exercise any bloody cruelty amongst these people: far be it from the hearts of the English, to give them occasion, that the holy name of God, should be dishonoured among the Infidels, or that in the plantation of that continent, they should give any cause to the world, to say that they sought the wealth of that country above or before the glory of God, and the propagation of his kingdom.

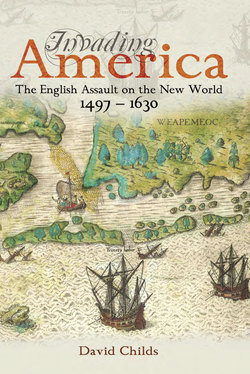

Massachusetts Bay Company seal. The apotheosis of hypocrisy: the Indian’s plaintive call for help was a travesty of the treatment that they were to receive.

Serendipitous geology led the Spanish to find gold where the landed in the new world. The English refused to believe that they too would not discover similar wealth and chose to ignore the evidence of its absence in the ores with which their ships’ holds were filled. (National Maritime Museum)

Yet, hidden from the public view, the Virginia Company, in 1609, informed the temporary Governor, Sir Thomas Gates, that his four priorities were:

1. To discover either a route to the Pacific or gold mines.

2. To establish trade with distant ports.

3. To exact tribute [i.e. forced payment in goods by the natives].

4. To establish local exporting industries such as glass-making.

The first of these remained the enervating chimera that John Smith railed against Christopher Newport for investing so much impractical energy. Newport had not only tried to portage a great boat over the James Falls at modern Richmond but had ordered the settlers to stop work on building houses and planting crops so that everyone might fossick for gold. ‘There was no talk, no hope, no work but dig gold, wash gold, refine gold, load gold,’ wrote Anas Todkill, while Smith himself in a memorable phrase spoke of ‘Freighting a drunken ship with gilded dirt’. As with Frobisher’s efforts before, the investors chose to ignore Newport’s assayed failure and continued to press for the ground to be opened up to yield its non-existent riches. Acting as an entrepôt was also an impractical aim as long as Spain retained its adamantine opposition to any English settlement in the Americas.

Examples of the ores brought back by Frobisher erroneously thought to contain gold. (National Maritime Museum)

The third priority represented a major geopolitical move. When he had returned to Virginia in 1608, Christopher Newport carried out the Company’s instructions by forcing a crown upon Powhatan’s head and presenting him with a double bed by way of acknowledging his regal status, while Powhatan confirmed his view of his position by stating that, ‘If your king has sent me presents, I also am a king, and this is my land,’ although his return gift of a second-hand pair of worn-out moccasins and a cloak might have just implied what the local ruler thought of this imposed relationship. Now the Company wanted to dispense with and dispel such hypocritical niceties: Powhatan was to be taken captive and forced to pay tribute while lesser chiefs would be forced to acknowledge King James’s overlordship. This was conquest in the Norman style, with each tribe being required to provide corn at every harvest and to labour weekly for the English. Feudalism, dying out in England, was to be re-established in America. It did not take hold, but from its failing sprang up a greater evil – slavery. At the time of the 1609 Charter, however, the secret orders guaranteed war where peace was the most important policy.

Outside the excavated remains of Jamestown the modern visitor can see a line of low-lying grassy banks which mark the houses and workshops of the artisans who were brought to Virginia to establish the settlement’s export industry. A short distance away down an old track is the remains of the glass works. A large mulberry tree also hints at early hopes of a silk-weaving industry: the fact that it was the wrong sort of mulberry for silk worms is an arboreal indication of the lack of planning that went into meeting Gates’s fourth target, which Smith also condemned by pointing out that the Baltic lands were far better able to export that which the investors demanded. Thus each instruction carried with it the seeds of failure and it was not until the settlers themselves decided to grow tobacco, or in the case of New England export furs, that commercial success ensued.

When the initial enthusiasm for shares diminished in the light of no quick return the Virginia Company hit upon another wheeze, which the King backed by the issue of the third Charter of Virginia in March 1611. This authorized a lottery to be held. With a first prize of £1,000, it proved to be an instant success and once more the coffers of the Company, but not the pockets of the investors, were filled.

The continuing failure of Virginia to deliver a sizeable and reliable return rekindled interest in the northern plantation, now renamed New England. Although this had been abandoned in 1608, interest in the area had remained because of both the great catches of fish netted from the waters off Maine and the proselytizing work of John Smith, who had published his work A Description of New England to encourage re-colonization, a venture in which he wished to play a key role. In March 1619 the King was presented with a somewhat grovelling and self-justifying, but short, petition for a new Charter of New England. By 3 November of that year the lengthy, fairly indigestible, Charter had been written and promulgated. Its main point was that it remained a West Country initiative, uncoupled from the arrangement with its London twin.

Those who still viewed the expanding world as one in which privateering had a part to play could also see value in retaining a settlement in Newfoundland, especially if the Government were charged ‘to maintain a couple of good ships and two pinnaces in warlike manner upon the coast’, for the sites selected lay not too far off the route home from the West Indies and were also a convenient halfway port of call for vessels bound for Virginia. St John’s had, of course, been claimed for the Crown by Humphrey Gilbert, but the Charter of 1610, which awarded the whole island to the London and Bristol Company, did not mention this fact. Instead it attempted to link London capital with Bristol experience to create a going concern based on managing the fisheries and, that inevitable chimera, mining for gold and other precious metals. However, the company had learned from the obvious errors committed by its Virginia forerunner. In particular the first settlers sent out to Newfoundland were mainly labourers, fishermen and people with practical skills who were instructed to settle away from swampy ground, to keep busy and to establish good relations with the few native people that they encountered in this land ‘so desolate of inhabitance’. The governor selected was also not an untested ‘gentleman’ but an experienced merchant who knew this new world well enough. The flaw in the Newfoundland Charter was the belief held by both propagandists and investors that settlement could create added value to the already efficient offshore fishing industry. It could not, nor could a land where survival alone was challenging enough provide a return to shareholders. Gradually, the latter, along with the gentlemen adventurers, moved away, but the labourers stayed. They needed no Charter to continue to eke out a living for they had sufficient land that they could call their own to support a family in freedom. Harsh as it undoubtedly was, many of them had more to lose by leaving than they would gain by remaining. More limpet than tree root, they clung on and survived.

The Charter for Nova Scotia, issued in September 1621, granted almost sovereign powers to Sir William Alexander over a tract of land stretching between Newfoundland and Maine which had previously been known by the French name of Acadia. In a supplementary document the King gave his reasons for making the grant as:

Having ever been ready to embrace any good occasion whereby the honour or profit of our Kingdom may be advanced, and considering that no kind of conquest can be more easy and innocent than that which proceeds from plantations specially in a country commodious for men to live in, yet remaining altogether desert or at least only inhabited by infidels the conversion of whom to the Christian faith (intended by this means) might tend much to the glory of God considering how populous our Kingdom (Scotland) is at this present and the necessity that idle people should be employed, preventing worse courses there are many that might be spared, of minds as resolute and of bodies as able to overcome the difficulties that such adventures must at first encounter the enterprise doth crave the transportation of nothing but only men, women, cattle, and victuals, and not of money, and may give a good return of a new trade at this time when traffic is so much decayed. Therefore we have the more willingly hearkened to Sir William Alexander who has made choice of lands lying between New England and Newfoundland, both the Governors whereof have encouraged him thereunto . . .

It is a succinct summary of all the reasons for plantation that had appeared in earlier Charters.

When, as had happened in earlier Charters, Alexander found that he could not persuade sufficient ‘idle people’ to head out to the commodious lands, and, finding that the enterprise was in need of money, he hit upon the ingenious idea of offering land for honours, centuries before Lloyd George, and later politicians, saw that titles were saleable assets. He persuaded the King to create a new order of twenty-two barons, each of whom would hold titles in Nova Scotia. The estates that accompanied the titles covered up to 12,000 acres each and were available for the down payment of 1,000 marks and the dispatch of six settlers.

But sextets wishing to sail for what was in reality a scheme to restore Sir William’s fortunes were not readily available and, apart from a military expedition to hold the land against prior French claims, little was achieved between the issue of the Charter and 1631 when, by treaty, the land was returned to France.

Ironically the Christian religion, or the zealously guarded Anglican version of it, delayed the departure of many who might have been expected to apply the high-minded desire of spreading the gospel which had been expressed in the Charters. Stuart England had a growing number of minority creeds, ranging from the sizeable old Catholic families to the newer Puritans and other dissenters. Many of these welcomed the opportunity to emigrate to the new world, where they were quite prepared to work as communities to establish viable settlements, provided that they were guaranteed freedom to worship. This King James was not prepared to allow, being influenced most understandably by the Catholic Gunpowder Plot of 1605. Both the 1609 and 1620 Charters included a paragraph that stated:

because the principal effect which we can desire or expect from this action, is the conversion and reduction of the people in those parts, to the true worship of God and the Christian religion, we should be loath that any person should be permitted to take passage that we suspect to affect the superstitions of the Church of Rome, we therefore declare that it is our will and pleasure that none be permitted to pass in any voyage which from time to time be made to that Country, but such as have taken the Oath of Supremacy . . .

The paragraph went on to state that the Company and appointed officials could demand of any settler that they swear the oath of allegiance and acknowledge the Act of Supremacy. Not even the most illustrious could ignore this ruling.

In 1629, Sir George Calvert, Baron Baltimore and an out-of-the-closet Catholic, cruising the American coast with his wife and family in search of a site for a settlement more in keeping with his requirements than he had discovered Newfoundland to be, put in to Jamestown. Here he was asked to take the oath, in accordance with the Charter, but refused to do so, after which he departed in haste for England, leaving his family behind. Once back at Court he did what the Virginians suspected that he would do, and persuaded King Charles I to grant him a Charter for the future Maryland, carved out of territory that the Virginians believed to be their own. When Charles published the Charter it proclaimed Cecilius Calvert, Baltimore’s son and heir, to be a person who possessed ‘laudable and pious zeal for the propagation of the Christian faith’.

The trials and tribulations of dissenters proposing to settle in New England were to be famously overcome and in a way that demonstrated that the days of the royal Charter were numbered. America had not yet sent out a cry to be given England’s huddled masses, and dissenting illegal and penniless exiles were not obvious shooins for one of the parcels of land, called hundreds, which the Virginia Company was trying to sell. Yet, few other pre-formed communities showed willing to travel across the Atlantic to an uncertain future, and even King James indicated that, although he would not approve, neither would he obstruct the passage of Puritans to the new world.

Thus, after much turmoil, misunderstanding and/or double-crossing, the Mayflower passengers pioneered the passage of people of faith. They did so as part of a new London-based joint-stock company, the indenturing terms of which they were still arguing over as they sailed. Yet, having managed to depart from Plymouth, charterless, on the day of the first disembarkation at Provincetown, Cape Cod, they produced a document, far shorter and much more useful than any Charter, which would reform not only the whole manner under which such ventures would be undertaken in future, but the way that incoming communities would regard themselves – less servility more self-worth. The Mayflower Compact must surely rate as the shortest revolutionary document ever scribed. Not that it appears, at first reading, to deserve that accolade, but what it introduced into the settlements for the first time was the concept of ‘mutuality’ and local democracy. Gone is the governing structure imposed from abroad, relying on the presence of ‘gentlemen’; gone is the desire to grub up the earth for gold or to seek for ways to Cathay; gone is the overarching requirement to create wealth for absentee investors; gone, in a word, is greed.

In the name of God, Amen. We whose names are under-written, the loyal subjects of our dread sovereign Lord, King James, by the grace of God, of Great Britain, France, and Ireland King, Defender of the Faith, etc.

Having undertaken, for the glory of God, and advancement of the Christian faith, and honour of our King and Country, a voyage to plant the first colony in the northern parts of Virginia, do by these presents solemnly and mutually, in the presence of God, and one of another, covenant and combine ourselves together into a civil body politic, for our better ordering and preservation and furtherance of the ends aforesaid; and by virtue hereof to enact, constitute, and frame such just and equal laws, ordinances, acts, constitutions and offices, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general good of the Colony, unto which we promise all due submission and obedience. In witness whereof we have hereunder subscribed our names at Cape Cod, the eleventh of November in the year of the reign of our sovereign lord, King James, of England, France, and Ireland, the eighteenth, and of Scotland the fifty-fourth. Anno Dom. 1620.

The very brevity and simplicity of the Compact make it a truly American text. The English Court was just not capable of such incisiveness: its Charters rolled on for page after page, often repeating the same lists and phrases. The Compact, in its entirety, was shorter than the part-paragraph of the third Virginia Charter quoted above, covering just the one topic of defaulting payments. On 11 November 1620, off Cape Cod, American public prose spoke its first words and what this infant Hercules chose to say was short, precise and clearly understandable. It was to remain so. The Bill of Rights, the Declaration of Independence, the Gettysburg Address and many more seminal documents are, in their clarity and pithiness, descendants of the style adopted in the Compact. And, like the Charters it superseded, the Compact had a dual role, for the fact that all the settlers signed it ensured it would be nailed to the door of democracy through which, eventually, all who entered the new world would pass.

Down in Virginia change was also afoot. In April 1619 Sir George Yeardley, the new Governor arrived under instruction to reform its dysfunctional governance. He started by abolishing the ghastly ‘Laws Divine, Moral and Martial’ and in their place established democracy, or almost. London retained control by appointing the six members of the Council of Estate but below this was established an Assembly whose twenty-two members were to be elected, two from each of the eleven settlements that lay along the James River. ‘Two from each’ – a form of representative government which exists in America to this day.

A mixture of fantasy (the mermaids) and reality (the Amerindian dwellings) are shown in this depiction of Walter Ralegh’s mythical welcome to the new world. Both fact and fiction needed to be employed to convince would-be settlers to emigrate; neither was a powerful enough persuasion on its own. (National Maritime Museum)

Thus in the space of one year a youthful, but differing, form of democracy was introduced into both halves of English America. However, like twins separated at birth by their original Charter into ‘two several Colonies and Companies’, Virginia and New England were to adopt different and divergent outlooks on life so that, like characters from the Bible, which they both held in high regard, they would commit matricide and fratricide until, war weary, they came together ‘one nation under God, indivisible, with liberty, and justice for all’.

There was one more step needed before the weight of the Charters could be lifted off the colonists’ backs, and this came about when it was agreed that the Massachusetts Bay settlement should be self-administered, which removed the need to meet the unrealistic expectations for a return on capital held by English-based shareholders.

The great difference between the founding Charters and their new world successors was not the belief in God, the ideal of liberty and the concept of justice, not even the pursuit of happiness, but that settlers could choose what enterprise to pursue and that, taxes to one side, the wealth which they gleaned from their labours would be theirs to retain within the boundaries of the land which they now considered to be their own. However, after over a century of deployment, those arriving in the new world would still have to conquer before they enjoyed their land in comfort.

In England, King James had lived up to his sobriquet of being ‘the wisest fool in Christendom’. Sandwiched between the fame of his predecessor, Elizabeth, and the fate of his successor, Charles I, this monarch, with his unhygienic personal habits and strange vices, has not been accorded the accolades deserved by the man who established the British Empire and had commanded the Authorized Version of the Bible to be translated and distributed. His wisdom is very apparent, even within the extremely verbose American Charters, for most of the near-fatal errors that affected the colonies were introduced by the Companies and not the King. The peculiar method of appointing and electing the original Council of Virginia, the emphasis on seeking for gold, the time spent in looking for a passage to the Pacific, the coronation of Powhatan, the demand for goods – all stemmed from the investors’ greed and not the King’s grant. In one thing only was James unhelpful, and that was in his objection to the ‘noxious weed’, tobacco, the production of which saved Virginia. Yet, even here, history might uphold the wisdom of the King: tobacco was to kill more of his successors’ subjects than ever did the Amerindians.

For as long as he felt able so to do, James indulged the Virginia Company and its investors, even altering their Charter: to impose better government; to provide more opportunities for settlers; to pursue bad debts; to include Bermuda, and, through its lottery, provide additional ways of raising money. In return he had seen nothing but bad management, bankruptcy and great loss of life. When the latter made headline news with the report of the massacre of 1622, the King was minded no longer to reform but to revoke. Following his reading of Nathaniel Butler’s exposé of Virginia at the time of the massacre, the critical views of which were independently supported by advisors whom he trusted, the King ordered, in May 1623, a Crown Commission to be established to investigate the Company’s affairs. There could only be one result, and on 24 May 1624 the Virginia Company’s Charter was revoked.

One year later, on 13 May 1625, the new King, Charles I, declared that:

to the end there may be one uniform course of Government in and through our Whole Monarchy, that the Government of the Colony of Virginia shall immediately depend upon Our Self, and not be committed to any Company or Corporation, to whom it may be proper to trust matters of Trade and Commerce, but cannot be fit or safe to communicate the ordering of State-Affairs, be they of never so mean consequence.

The age of the private Company had ended; the age of the royal colony had begun.

There are two Charters that are seldom mentioned among those that affected the development of English America. The first was the one which, on 31 December 1600, incorporated the British East India Company. Although many of the voyages that took place under its auspices ended tragically, the ships that returned safe home swamped the market with cloves, peppers, silks and saltpetre. When, in 1609, the books were closed on the combined results from this Company’s first two voyages, a profit of 95 per cent was declared. Nothing exported from Virginia could match that until tobacco became a major crop and furs a valuable catch. Certainly ship masts, staves, clapboard and sassafras could not compete. Those with money to invest – and many people, like Sir Thomas Smythe, were active in both the Virginia and the East India Companies – were far more likely to consider that, despite the shipwrecks and the seizures, trading voyages to the East Indies offered a better return on capital than did settler ships sailing to America. Nothing came of the other Charter, issued to Sir Robert Heath in 1629, but it is of note because it granted to this friend of King Charles the land lying between 31º and 36º North, the Carolinas, stretching well towards the region previously jealously and murderously protected by Spain (St Augustine was only sixty miles further south). As a statement of confidence in colonialism it would be hard to beat but, as it was never acted upon, it was never contended.

The Charters had been the unique way by which the English sovereign apportioned the new world to his or her subjects. It was a formulaic patent with little difference between that awarded to John Cabot in 1496 and that granted to Sir Robert Heath in 1629. All emphasized conquest, occupation and conversion. At the end of that long century a few square miles were occupied but not fully controlled, let alone conquered, and a few ‘barbarous men’ had been converted. The Charters presented to Cabot, Gilbert, Ralegh, Alexander, Heath and the northern Virginia Colony had come to nought; the three issued to the Virginia Company of London had proved unworkable; that for Maine, issued to Gorges and Mason, had led to a few huts being erected; Newfoundland would have struggled on without a Charter, as would have the settlement at Plymouth, while Massachusetts Bay guaranteed its success by taking the paperwork with it. Neither did the Charters of themselves address the needs of the invasion period about which its language was so up-beat. They were documents designed to ensure a quick return for the petitioners, not operational orders for invading and occupation forces. They should have been.

Map 2: The division of Virginia under the First Charter, 1606