Читать книгу Ringside Seat to a Revolution - David Dorado Romo - Страница 46

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеwith a gun once in Sonora when she refused to stop

healing the sick and later in Clifton, Arizona when

Tomás refused to let Teresita marry the man of her

choice. On both occasions Teresita calmly stood her

ground until her father gave in. Furthermore, there

was no bitter breakup between Teresita and Aguirre,

which would have been expected if he was sur-

reptitiously using her name to support a

movement she didn’t believe in. On

the contrary, she left El Paso on

good terms with Aguirre and

would later name her first

daughter Laura in his honor.

It’s understandable why

Teresita would publicly

deny her involvement in

the border uprisings. She

feared for her safety.

Díaz had called for her

extradition. She was con-

stantly under government

surveillance. Rumor had it

that the Mexican govern-

ment would try to kidnap

her. She was the victim of

more than one assassination

attempt.

Yet there’s quite a bit of evi-

dence that suggests that Teresita was

much more involved in the insurrec-

tion than she was able to admit to

the press. Before the Teresista upris-

ings in the summer of 1896, Lauro

Aguirre hired El Paso photographer

Charles Rose to take pictures of Teresita. Aguirre

handed Rose a text that he wanted printed on the

back of the photograph. It was a short biographical

sketch of the young healer entitled “Señorita Urrea,

the Mexican Joan of Arc,” which spelled out Teresita’s

role in the movement to topple the Díaz regime.

Miss Urrea, during her first year of exile, said

nothing against the Mexican government;

but she did quietly help prepare for the

struggle against it. El Independiente, which is

written by her and Mr. Lauro Aguirre, has

attacked the injustices committed by the

Mexican government. Her great moral quali-

ties her love, unselfish dedication and the

truth of her denunciations against the

Mexican government make her the only per-

son who is able to transform the country of

Mexico. Only she can topple an oppressive

tyranny—that burns villages, exterminates

entire races and murders children.

We believe that she will overthrow the

actual government and will lead the Mexican

people to change their political situation. We

see her as the Mexican Joan of Arc. That

even the government of Mexico

sees her as we do is brought to

light by the tenacious manner

that it has persecuted her.

Miss Urrea has escaped

being assassinated or

poisoned on various

occasions.90

When Charles Rose

received the text, he was

reluctant to print it. The El

Paso photographer feared

that Aguirre had written this

without Teresita’s consent.

Rose approached Don Tomás

and told him he was afraid they

would all get in trouble for pub-

lishing such inflammatory material

on the reverse side of Teresita’s pho-

tograph. “I saw Mr. Urrea, and with

the help of an interpreter, I told him

that there may be some statements in

the document that the Mexican

authorities might find objectionable,”

Rose later informed the Mexican con-

sulate. “But he merely suggested that I leave my name

out of the document.”91

One of the dead Teresista rebels who was killed

at Nogales on August 1896 was carrying the photo-

graph of Teresita with the “Mexican Joan of Arc” text

on the back. Another was carrying a lock of her hair.

Still another dead revolutionary carried a letter read-

ing: “Brothers, continue to prepare yourselves for the

11th [of August, 1896] for we shall join you and lift

our voices together with you. Do not fear, for we will

enter into Sonora together. That’s why I say to you

that you must be ready. I will arrive at Nogales at

night. Peace be with you.—Teresita Urrea and John

the Baptist.”92 (John the Baptist may have been

Aguirre’s code name.)

The American authorities in El Paso kept close

watch on the Urrea home for signs of subversive

41

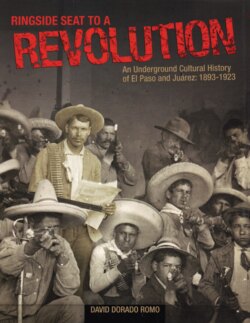

Teresita Urrea and puppy, ca.

1892. (Southwest Collection,

Texas Tech University.)

90

Lauro Aguirre, “Señorita Urrea, the Mexican Joan of Arc,” Holden Collection, Texas Tech University.

91

Brianda Domecq, “Teresa Urrea: La Santa de Cabora,” essay published in Jesús Valdés Vargas’ (ed.) Tomóchic: La revolución adelantada, p. 39.

92

Ibid., p. 41.