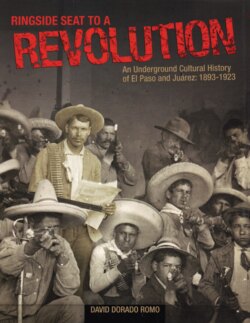

Читать книгу Ringside Seat to a Revolution - David Dorado Romo - Страница 59

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеEmma Goldman spoke in El Paso on March 12, 1910.

(El Paso Times, 1910.)

anarchist individuals and organizations. They met

with members of the IWW, with Spanish anarchist

Florencio Bazora and with Jewish-American agitator

Emma Goldman—whom the El Paso Times mocked as

“the Queen of the Anarchists” during her visit to the

city in 1910.

54

Ricardo found inspiration in his own country for

anarchism as well. The concept of communal owner-

ship of property without the need for centralized

authority had been a natural way of life among the

indigenous communities of Mexico for thousands of

years. But to a large extent, his anarchism grew grad-

ually from his own direct experiences and political

reflections.

Experience taught him that governments, no mat-

ter what they called themselves, could be equally

repressive. In Mexico, the Magonistas were persecut-

ed and imprisoned for their writings by a government

run by a dictator. In the United States, they faced sim-

ilar persecution at the hands of a government that

called itself a liberal democracy. After the Magón

brothers went into exile in 1904, American govern-

ment agents and private detectives hired by the

Mexican government hounded them and their collab-

orators wherever they went. It didn’t matter where

the Magonistas tried to hide—Laredo, San Antonio,

Los Angeles, San Francisco, Sacramento, Toronto,

Montreal, El Paso—the agents always found them.

The United States Postal Service, for years, opened

their mail and handed it over to the Mexican govern-

ment. The Mexican radicals were constantly in and

out of American jails on the charges of libel, sedition

and neutrality law violations.

After years of organizing, writing and meditating

on history, Ricardo Flores Magón came to the conclu-

sion that all forms of centralized government should

be abolished. He predicted that any revolution in

Mexico that only aimed to replace one centralized

government with another—whether run by a presi-

dent or a revolutionary junta—was bound to end in

failure. “The same thing has always happened, every-

where,” Ricardo wrote in 1908:

A flag is raised with calls for more or less

important reforms; the poor follow their

lead; they struggle; blood is spilled more or

less abundantly and if the revolution tri-

umphs, a congress is formed to put into law

the ideals that pushed the masses to take up

arms and fight. The congress is attended by

individuals with all kinds of ideas, some

advanced, others reactionary, most others

moderate, and during the struggle between

all of these tendencies the aims of the revo-

lution wither, lose their vitality and after

many months or years, laws are approved

that don’t even slightly resemble the ideals

so many gave their lives for.121

Even if “by a miracle” some of those ideals that

inspired the revolution are decreed as law, Magón

explained, the rich inevitably rebel against such a

program and “the people, without bread, listen to the

bourgeoisie tell them they must compromise.” The

results are a new government little different from the

last. Only an anarchist revolution, Magón argued,

governed from the bottom up by a loose federation

of autonomous worker and campesino communities

could prevent this from happening once more.

And where would be a good place to launch

such a revolution from?

Why, El Paso, of course.

121

Ricardo Flores Magón to Enrique Flores Magón and Práxedis Guerrero, June 13, 1908. Correspondencia, p. 379-380.