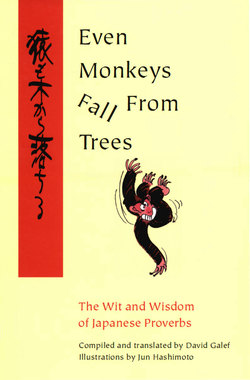

Читать книгу Even Monkeys Fall from Trees - David Galef - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеForeword

by Edward G. Seidensticker

The primary definition of “proverb” in the Oxford English Dictionary is very careful: 11 A short pithy saying in common and recognized use; a concise sentence, often metaphorical or alliterative in form, which is held to express some truth ascertained by experience or observation and familiar to all; an adage, a wise saw.”

The three words before “express” follow the advice of Atama kakushite shiri kakusazu (English equivalent: “Protect yourself at all points”): foresee challenges and attacks and take measure against them. If the Oxford did as the small desk dictionaries I have with me do, and dispensed with the qualification, then the definition would be in error. Sometimes proverbs fly in the face of “experience or observation,” and sometimes a proverb will contradict another one. Kyō no yume, Ōsaka no yume (no. 50) is vague and subject to several interpretations, some not completely in accord with common sense. Several proverbs advising caution are contradicted by Koketsu ni irazumba koji o ezu (no. 88), urging us to trespass upon a tigress’s den.

Proverbs are what people are always saying. In this they are akin to cliches, but they are different from cliches in that they have a touch of poetry. They make lively use of imagery and they are sensitive to the music of language. They say the things that people think important in ways that people remember. They express common concerns. So a collection of proverbs is a compact treatise on the values of culture. Matching sets of proverbs from two cultures make a treatise in comparative sociology, or cultural anthropology.

It need not surprise us, though it should interest us, that the same proverbs are to be found in very different cultures. The lot of the human race is similar the world over. That not all the proverbs of one culture are to be found in another need not surprise us either, and it should interest us very much. It demonstrates that the concerns of the two are not identical. It ought to shake us a little from our parochialism.

Inevitably, Mr. Galef does not always find perfect English matches for his Japanese proverbs. Some of his equivalents do not sound like proverbs, and some do not seem precisely equivalent. He makes note in his Preface of an excellent example, the one about the nail that sticks out (no. 43). “Don’t make waves” is ingenious, but it seems more an injunction to moderation than to conformity. The heart of the matter is that Americans, for example, are not exhorted by their proverbs to conform as Japanese are, so the quest for a perfect equivalent is probably doomed from the outset. It would be hard to find Japanese equivalents for some of the more puritanical of Anglo-American proverbs (“Spare the rod and spoil the child”), and Mr. Galef has perhaps not been entirely successful in finding an English equivalent for a very Buddhist one, Ko wa sangai no kubikase (no. 76), also about children.

I do not mean to reprove him. He has done his work well, as has his illustrator, Mr. Hashimoto. These little frustrations are, as I have said, inevitable, and they make the book more interesting. It is a likeable book, and it tells us much about Japan.