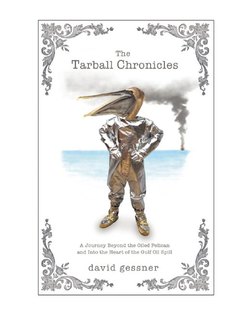

Читать книгу The Tarball Chronicles - David Gessner - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPRELUDE: INTO THE GULF

It is June and you are at a cookout at a friend’s house, a barbeque with all the kids playing in the backyard. You have just gotten back from traveling and you are happy to be home. For the last fifty-nine days millions of gallons of oil have been gushing into the Gulf of Mexico, but that is not your concern, not your problem. You want nothing to do with yet another dismal, depressing environmental story. You live in North Carolina and the Gulf is almost a thousand miles away. Yes, you care about the environment, so you should be thinking about the oil spill, but you’ve put on blinders, as you often do when the harsh light of big news events blares down on you. There is too much to think about, after all, and right now you are looking out at your daughter jumping on a trampoline, and the spill is the furthest thing from your mind. You drink your second beer and think that life is pretty good, pretty good indeed.

But then suddenly a friend is standing in front of you, and he insists on talking about the spill. He tells you of a live video stream he has seen from a mile below the surface and of the sight of a single curious eel peering at black-red goo pouring from the spill’s source, the busted Macondo well. He wonders what it is like for the people living down in the Gulf, and despite yourself and the beer and the sun on your face and your happy daughter playing, you start to wonder too. “You should be down there,” he says. “You write about nature.” You start to explain that that is not the kind of nature you write about—you write about birds and the coast, and you are not a journalist who chases stories. But then you stop explaining, and defending, and think simply: “Maybe he’s right.”

Over the next week the idea builds in your head. Maybe the Gulf is where you should be. Summer plans, family plans, rearrange themselves in your brain. You have a somewhat strained talk with your wife about your new plans, and, since there is no other way to get there on short notice, you decide to drive. “When will you go?” your wife asks, and it turns out your answer is “Right away.”

A magazine gives you an assignment to cover the looming fall bird migration, but this is about more than birds, you know that already. When you finally decide to leave you do so in a mad rush, throwing everything in the back of your car and heading out without any real plan. Of course you are aware of the hypocrisy of traveling eight hundred miles in a vehicle powered by a refined version of the same substance that is still pouring out into the Gulf waters—but now you are driven. Now you need to see the oil. You’re not sure why. You have heard the Gulf called a “national sacrifice zone,” and maybe you want to explore this idea of sacrifice, of giving up some of our land, and our people, so the rest of us can keep living the way we do. So you go down, heading toward the Gulf.

Which gives you some idea of how I found myself sitting in a booth at an Applebee’s on the border of South Carolina and Georgia. My waiter, a chipper young man named George, asked me where I was heading, and when I told him, in a somewhat reluctant and grumbling fashion, I expected him to chirp “Great!” and hurry off to get my fries and beer. Instead he thought for a minute before launching into a little sermon.

“We think it’s happening down there,” he said, jerking his thumb behind him, toward the wall with the sports posters on it. “But we’re part of it, too.”

I snapped to attention.

“It’s all tied together,” he said. “The oil we use in our cars and the oil that’s washing up on our beaches.”

I felt like standing up and clapping. How did this George understand something that the major media outlets couldn’t seem to grasp? It turned out this was another reason I had decided to throw everything in the car and head south. It seemed that no one in the national media was writing the bigger story, or at least the longer story, and I was pretty sure that the one oil-covered bird they kept trotting out for TV was not the story. “No more bullshit” was my blunt, businessman father’s favorite saying. No more bullshit indeed. This time around I would experience a story firsthand instead of letting the national media take me on its knee, like a kindly uncle, and tell me its sweet and homogenized version of the truth.

The next morning I drove through Georgia, mulling over my Applebee’s epiphany. My waiter reminded me of another natural philosopher, John Muir, who traveled this same route by foot nearly 150 years ago. “When we try to pick out anything by itself,” Muir said, “we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.”1 Yes . . . synapses snapped and connections crackled as the miles passed and I drank too much coffee. Wasn’t the spill hitched to everything? Already the disaster seemed to be trying to teach me something, in dramatic fashion, a lesson that the world kept teaching me but that I had been slow to learn: on this planet nothing is apart from anything else—all of us, human, plant, animal: intertwined.

I drove all day. A friend in Mobile, Alabama, had offered me a place to sleep, and I had planned to go there, but then fate, in the form of weather, decided otherwise. A thunderstorm bullied me eastward, toward the Florida Panhandle, until I noticed a sign for a beach I had seen on the news a week before. That beach was known for its famously white sand, at least until the caramel sludge started washing over it. As I continued along the shore I noticed dozens of cleanup workers wavering through the mist like a ghostly prison crew in fluorescent vests, sweeping the sands. There were a couple hundred workers in all, and at first the scene made no sense, the people seemingly disembodied and floating. I soon learned that these workers—many formerly unemployed and mostly men—were being paid eighteen bucks an hour by BP to pick at the sand. I also learned that their job was to gather tarballs and toss them into huge plastic bags, then bring the bags to the command center where they were weighed and hauled away in trucks. Almost all of the workers were black, and I got the feeling that most of these men, many from the nearby city of Pensacola, hadn’t spent a lot of time at this particularly touristy beach before the last few weeks.

The second level of command—the sergeants—didn’t exactly look like beachgoers either. I pulled over and watched them for a while. Muscular but overweight—almost all white, incidentally—they barked orders and drove around in fourwheel-drive ATVs that looked like amped-up golf carts. At first I thought that they might enjoy their little taste of authority, but they never smiled. No one seemed to be having a good time.

“Don’t ask them any questions,” the girl back at the beer store had told me. “BP won’t let them talk to civilians.”

Her wording had sounded strange at first, but not after I saw the workers spread over the beach: they did, in fact, seem like a sluggish, corporate army.

I moved on to explore the campsites, scouting for a place to put up my tent, before eventually heading back to the beach. Once there I walked down to the water’s edge, my first real encounter with the spill, and found the sand covered with tarballs. Though they didn’t look like balls exactly. The small ones looked like dried rabbit turds or kernels of a not-particularly appetizing cereal. The larger ones were maps of rust-brown countries or jigsaw puzzle pieces, some the size of cow patties.

Other than the workers, I found only one person on the beach: a man sitting in a foldout chair and pointing a camera at the water. James was a surfer whose skin had been burned a crisp brown over the years. He was also an amateur photographer. He told me that the local surf report now specified where the oil was and wasn’t each day, but that one day, when he went to one of the spots where it supposedly wasn’t, his wife’s white bathing suit turned gray.

We had been talking for a little while when a truck with Texas plates pulled into the parking lot and a small family—dad, mom, and daughter—piled out. Before long the little girl was swimming in the oily water, holding hands with her mom. I wondered if I should say something. Then the man, the father, called out to them, not out of concern for their safety, but because he had stumbled upon a giant tarball. James had shown me the same tarball earlier, saying it was the biggest he had yet seen and suggesting that he should bring it to the attention of the EPA officials. But the Texas guy was now laying claim to James’s specimen, apparently interested in taking it as a souvenir or trophy. James was a peaceful man and simply shrugged when the Texas guy picked up the lump of oil and carted it off. The little girl, now out of the water, became defensive when she heard me suggest that James had rightful claim to the tarball.

“If he touches that tarball my daddy will kick his ass,” she said.

She couldn’t have been older than eight. The man placed the tarball in the truck bed, a toxic prize for home.

“They’re real good on the grill with a little paprika!” James yelled after them as they drove off.

Soon after James packed it in, closing his chair and taking his tripod and saying good-bye. I continued down the beach, staring out at the green surf. While I expected to find ugliness here, what surprised me was the beauty. When I had first driven through the gates to this beach—a park designated as a national seashore and therefore undeveloped—something lifted inside of me. Wind swept across the thin scrap of land and birds carved up the air. It felt like the end of the earth, which it was. There were no buildings in sight, just one road running down between a spine of dunes, and my car splashed through puddles of saltwater. The surf frothed and sand blew from the ocean back to the sea oats and marsh that made up the island’s leeward side, and terns—sharp angular birds like living check marks—rose up from the dunes and screeched defensively, protecting their colony. As someone who has always loved the ocean, I understand the appeal of crossing over a bridge or going through a gate and finding a place apart, a place to get away from the human world and into the world of birds, water, wind, and sand. Despite everything, that was how I felt upon entering the park. It was thrilling, really. But a “place apart” also implies seclusion and separateness from the world. It went without saying that, at that moment, the beach surrounding me was anything but.

Eventually I came upon a particularly ugly patch of tar, something the Texas family might have wanted to lay claim to. As I looked into these clumps of oily turds I began to suspect that this time we had really done it. I thought: We have passed a point, and the fact that many of our current actions are suicidal must be becoming obvious to even the most casual observer of the natural world. We have soiled ourselves. Less elegantly put, we have shat ourselves.

These were the kind of things bubbling in my head as I walked from the beach up the driveway to the ranger station. And then I saw it: This . . . what? . . . this symbol of what has gone awry. It was a truck, a white truck, oversized and muscular, larger than any truck has a right to be, with its motor running and windows up, air-conditioning blasting. I’d vowed not to use my AC during this trip, and had kept to that vow so far. It was just a symbolic gesture—being that I had just driven eight hundred miles down to the Gulf—but gestures felt like the only meaningful actions available. I knew I had no right to be outraged.

But outraged I was. When I inquired inside the station it turned out that the truck belonged to a fellow journalist, a guy making a documentary about the tarballs. Shouldn’t he, of all people, get it? He was talking to the rangers, something about the evils of BP, and I didn’t know what got into me—it’s not the kind of thing I usually do—but before I could stop myself I interrupted him by saying: “So maybe you should shut off your truck when you’re not in it?”

Right away I felt bad and he got defensive, muttering about how hot it had been out on the beach and how his personal energy use was “just a drop in the bucket.” Soon I found myself wishing I hadn’t said anything and feeling guilty when the guy stormed off.

I expected that the rangers would be put off by my behavior, but instead they acted amused. After the truck guy was gone, one of them turned to me with an unexpected smile and started talking. Right away I liked her—she had sympathetic eyes, a quick wit, and an obvious love for the beach. Before long she was showing me pictures of what she called “her” beach, in the same way someone else might show you pictures of her kids. She held out one of a hidden place she went to every day for lunch, tucked between the dunes, a place far away from the tourists where she could “get away.” But the tarballs had discovered her secret. Yesterday she’d had an apple with lunch and showed me a picture of a huge tarball dwarfing the leftover core.

As we talked she informed me that the fort that gave the seashore its name was built after the War of 1812 to protect our young republic from British invasion. Which had worked pretty well until three weeks ago.

She also told me about watching as the BP supervisors and contractors and their work crews descended on the park. It was a strange twist. “The British are coming!” she’d wanted to yell. And then, before she knew it, the British were here.

“We used to be in charge of this beach,” she continued. “Now we are bossed around by these people. But they don’t know the place. They trample things. At first they ran right over the turtle nests in their ATVs.”

She described the dark day the caramel-colored tide came in and coated her beach.

“It was the color and texture of a Baby Ruth bar left out on a hot dashboard,” she said.

What she felt was a sense of creeping powerlessness.

“It’s not just the oil on the beach, it’s the fact that we’re not in control. We’re like people in an occupied country.”

We exchanged e-mail addresses and phone numbers and promised to keep in touch. Before I left, though, I asked her if I was allowed to swim in the water. I have traveled the coasts a lot in the past few years and at every beach I’ve visited—from Alaska to Cape Cod to Nova Scotia to the Outer Banks—I have made it a point to mark my arrival with a plunge into the ocean. I may not have liked seeing the little Texas girl playing in the surf but that didn’t mean I didn’t want to see myself in it.

She shrugged.

“We don’t make the rules anymore, but BP’s party line is: ‘If it looks clean you can go in.’”

“That’s pretty scientific.”

“Yup,” she replied, shaking her head but still smiling.

After bidding her good-bye I hiked back down through the dunes. Before long I felt better, swinging my arms and looking out at the water. The world opened up: a rush of wind and salt spiced with the vague smell of oil. An osprey flew above the surf, peering down for fish. Up the beach from the tarballs was a sign for a sea turtle nest where, below the ground, a newborn Kemp’s ridley lay snug in egg and sand. I knew that soon enough the turtle would emerge and begin its crawl to the oily sea.

Far off in the distance, I could still see the tarball farmers. But they were tiny chess figures way down the beach. It’s odd to say on a beach where hundreds of men wielded shovels and trash bags, but as I stopped to crack a beer, I was filled with that sense of solitude and euphoria that has always drawn me to the coast. I moved away from the workers and thought that maybe I had reached a place where I was relatively alone. That is until I noticed a woman walk down to the water before circling back to a hummock. When she reached the hump of sand she bowed her head as if in prayer. I walked over to say hello but then I saw the flowers and realized that she might be spreading the ashes of a loved one.

Or she might have simply been mourning for the beach itself. Either way, I gave her another mile of space before finding a spot tucked into the dunes. There I took out my journal and binoculars and studied the surf and sky. I watched a single tern dive, slashing downward and then lifting back up into the air. Success! It flew upwind with a sliver of minnow in its mouth, heading back toward its colony in the dunes.

So this is our national sacrifice zone, I thought. It was my first good view of the Gulf of Mexico, whitecapped and windblown, and of course just looking at the water was not enough. I stripped down to my boxers and walked to the edge. Then, after some brief hesitation, I dove in and began swimming out into the sea.

“If it looks clean you can go in,” says BP. As if anyone, even the diving tern, with vision six times better than ours, can see the quality of the water it dives into. As if anyone, even the tern, can possibly peer into the fish it holds in its mouth and see the gift of chemicals inside, chemicals perhaps already doing their ugly work. As if it can discern that once again human beings somehow can’t comprehend the simplest of notions, one the bird knows deep in its hollow bones: that everything in the world is connected, and that when you soil one thing you soil it all.

Unlike the bird, I had some idea of what I was getting into. But I swam anyway, rising and falling with the waves. It was an unctuous baptism but a baptism still. I had come a long way and now I was part of it, and I knew, as my philosopher-waiter reminded me, that we were all part of it. I also knew this: There would be no more sitting on the sidelines. If the tern was going down, so would I.

And while the water might be poisoned, for the moment it felt good. I am glad to be here, I thought. There is no other place to be.