Читать книгу The Tarball Chronicles - David Gessner - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE GREEN SUN RISES: JULY 16, 2010

I’ve been down here ten days now. From Fort Pickens I traveled to Mobile and from Mobile to Bayou La Batre, fictional shrimping grounds of Forrest Gump and real shrimping grounds to hundreds of now-unemployed men, and from there on to Mississippi and Louisiana. I keep thinking things can’t get any stranger but then they do. Everyone is either angry or giddy-drunk with the money that BP is handing out to assuage their bile. This afternoon I saw New Orleans for the first time and was tempted to stop for a drink and some pommes frites, but blew right through, intent on getting down here, a hundred miles south of the city. I am edging closer to the source. As I left New Orleans I couldn’t help but feel that I was driving downhill as well as southward, even though the city itself is, in places, below sea level.

The nearer I get the more obsessed I become with the need to see the rig, the oil, the whole ugly mess of it. It is dark, past nine, by the time I finally close in on the town of Buras. I am feeling a little paranoid, and not just because I am foolishly sipping the beer that I hold between my legs as I drive. Hardly any vehicles are on the road but the few that are seem to be almost exclusively cop cars. I toast them in the rearview after they have passed, acting bold but feeling scared. In the darkness I can see nothing other than the road, but I sense that the land is growing narrower, and that big water is closing in from both sides. The place bursts with water, water hungry to swallow the thin and tenuous land. On my left is the Mississippi, straining against the earthen mounds of levee, and on my right are millions of acres of wetlands. Straight ahead lies the Gulf and the blown Deepwater rig.

Following instructions, I pull a U-ey after the giant flagpole and circle back to the Cajun Fishing Adventures lodge where I will stay. Inside, the cavernous lodge is almost empty. Empty except for Lupe, short for Lupida, the Mexican cook and caretaker, and a small group of men and women who look less like fishermen or hunters than a band of scruffy Ultimate Frisbee players. The lodge’s emptiness seems odd, given that I noticed several No Vacancy signs on the way down, but I forget about this when Lupe hands me a glorious sandwich stacked high with turkey, mayo, tomatoes, and lettuce. I wolf down the sandwich with a beer from my cooler, and before long Lupe and I are chatting away despite the fact that she barely speaks English and that my Spanish is comically primitive.

When we are done talking, I walk over to say hello to the other lodgers, approaching the only one who seems close to my age: a pretty woman who tells me her name is Holly. At first I can’t figure her or her crew out: clearly they are not like the folks who usually populate this place, burly men who come down from Michigan or Indiana to hunt and fish and chew and spit. Not only are they a lot younger than me, but their general vibe says “California.”

The mystery is solved once Holly tells me that they are part of Jean-Michel Cousteau’s film team, here to make a movie about the oil spill and its effects on the sea life. As a kid, I was a big fan of the great Jacques Cousteau and loved his undersea adventures, and now I am more than pleased to be in the presence of his virtual descendants, a team of divers and cameramen. Since Jean-Michel is not here, Holly is in charge, and after we chat for a while, she introduces me to another member of the group, a young cameraman and scuba diver named Brian.

Brian and I hit it off right away. He is low-key with a ready sense of humor, and before long we are swapping war stories from our time so far in the Gulf.

“We were the first people to dive down and film what was happening underwater,” he says. “We dove right into the oil. When we got back the neoprene on our diving suits had bubbled up. It looked like it was curdled.”

We talk for a while more and then Holly, unprompted, does something wonderful. She invites me to come along the next day when they will be flying out over the rig in a helicopter. I thank her for her generosity. Since my plan was to have no plan and since my contacts in the area are nil, this is a ridiculous bonanza.

To top off the night, Brian and I head out to the patio in front of the lodge and drink a couple of beers. I tell him how I felt paranoid during the drive down and mention all the cop cars. He assures me I wasn’t being paranoid; it’s true that everyone who isn’t working for BP seems to be a cop, and cop cars lurk behind every sign and shrub. There is talk, too, of planes heading out at night to spray dispersants on the water under cover of darkness.

“Napalm” is one local name for Corexit, the chemical they spray. Another is “Agent Orange,” in part for the way it stains the water and shore.

“It’s a very strange place,” Brian mutters, shaking his head.

As if on cue a squat little truck appears near the top of the driveway. He points his beer at it and tells me to watch.

“It comes every night.”

It looks innocent at first, like it’s selling ice cream, minus the tinkly siren song music. Brian says it patrols the streets after dark, happily bouncing along and spraying a huge cloud of God-knows-what.

“I assume it’s some sort of insecticide,” he says.

It turns in at the lodge and rumbles down the driveway, as if to make sure it sprays us where we sit on the porch. We sip our beers and stare as the little toxic ice cream truck trundles by.

I wake at five and decide to drive down to the southernmost tip of Louisiana, the very end of the land. A chronic early riser, I make a cup of coffee and throw my telescope and binoculars in the car and head down, expecting the road to be deserted. But within minutes I am caught in a bizzarroworld rush hour on a too-dark, single-lane road, the cars practically bumper to bumper. I am driving south in hopes of seeing some birds, but the other drivers on this morning pilgrimage have very different goals in mind. Some are local but many have come from far away, beckoned apparently by the smell of opportunity that often wafts up from disaster. They’re headed to a harbor where they will climb aboard a motley collection of ships that includes pleasure boats, shrimp trawlers, and charter fishing boats—all called “Vessels of Opportunity,” the fine Orwellian name dreamed up by BP. VOOs, as they are known locally, are the ships hired by the oil giant to search for oil slicks and lay boom, a kind of absorbent guardrail, to stop the oil’s advance. Down here money is suddenly gushing along with oil, though not everyone is getting in on the fun. A few of the boat owners have managed to get rich by earning a couple grand or so a day to have their boats sit idle, as backups, giving birth to another new local term: “spillionaire.” But most of the local men are simply struggling to make up for lost income, lost because they can no longer make a living catching fish or shrimping or trawling for oysters.

Hundreds of cars pour south toward the harbor, all going from roughly the same origin to the same destination, from their homes and hotels in the north to the harbor in the south, but none of them doing anything as unmanly as carpooling. “You should see it on a weekday,” says the guy buying a tin of Skoal at the convenience store. I ask him if he’s from here and he says he’s not. He’s from Texas and is staying in the barracks-style hotel down the road that is putting up a lot of workers.

The cars crawl south for another mile or so before turning through a gate in a chain-link fence topped with barbed wire where two guards are posted. I pull over on the other side of the road as the commuters report for duty at what looks like a military installation. Paranoia fills the air here, thick as the humidity, and as I watch the workers park their cars, I also keep half an eye out to make sure no one is watching me.

It’s still the bluish dark of early morning as the workers trudge over to their Vessels of Opportunity. Street lamps spray down unnatural aureoles of light as if putting the men on stage. I know I’m in the thick of it now. Proof of that is the sign across the street that reads “Halliburton Road—Do Not Litter.” Good advice. The men climb aboard their boats. One of the small, sad sights down here is watching the boat captains, seamen who have likely not worn life preservers since they were toddlers, all buckled up in their vests as they putter out to sea each morning. It looks like a badge of shame, which of course it is, beholden as these men are—not to their own government, but to the liability lawyers of a multinational corporation. The life jackets are just a physical manifestation of an ugly fact: when you sign on with BP you also sign away the right to criticize the company.

It’s hard to explain to someone who hasn’t been here how pervasive BP’s presence is. I think of a talk I had with Ken Heck, a scientist who works at the Dauphin Island Sea Lab in Alabama. Heck has been commissioned by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to help figure out how to deal with the effects of the spilled oil on sea grass. This is challenging enough in and of itself, but made more so by the fact that BP has been included in all the discussions the scientists have had.

“It’s kind of paradoxical,” Heck said. “The way it’s set up, BP is involved in every step of the scientific process. That means they know the problems we are having and what our weaknesses are. They’re in on the conference calls, so let’s say I mention that we really don’t have any good pre-oil data from this one coastal area. Well, now they know this and later they can use this when we press for damages and they say ‘Not a valid claim.’

“This is particularly troubling when it comes to damage assessment, which is mostly what we are doing now. They’re not just in on every phone call, they’re out in the field with us. Their representatives came with us when we went to take pre-oil samples on the Gulf Islands, before the oil got this far. They watched us like hawks. You had to put on plastic gloves every time you took a sample to avoid cross-contamination. Well, one time we forgot to change the gloves. And you know they’re noting that and that later, when the divorce comes—and everyone knows the divorce is coming—they will say, Well, isn’t it true, Dr. Heck, that you didn’t change your gloves on every sample?’

Now, as the VOOs putter out to sea, I find myself irked by the fact that a whole region is beholden to a company. I hadn’t anticipated feeling this way. I am no Libertarian and I won’t be attending any Tea Party rallies anytime soon. But what about the original Tea Party? What about our autonomy and independence and responsibility to our own citizens? Questions bubble up. How can environmental groups and scientists be reporting to a British oil company? Are we really buying this crap? I can’t quite get my head around the fact that BP’s representatives are out on scientific survey boats, noting facts that might be useful as evidence in some future lawsuit. Or that their minions have been allowed to run the show at Fort Pickens, which is, after all, a national seashore.

Almost everyone along the Gulf seems to have signed a deal with the devil, a devil that in this case isn’t represented by horns and pitchfork, but by BP’s green and sunny logo. How can so many of our organizations, scientists, fishermen, and workmen be working for a foreign corporation? How about someone sensibly saying, “Hey guys, I don’t know about you, but it seems kind of wrong to me to hand over so much power—so much of our, excuse the word choice here, freedom—to a foreign corporate entity, particularly one that just soiled our waters and coasts.” Sure they should pay for the mess, but here’s an idea: what if we bossed them around and not them us?

I’m feeling worked up as I drive farther south, but the place quickly pulls me out of my overheated head. Soon I am splashing through three feet of standing water where the river has rushed over blacktop. My headlights flash on impromptu wetlands that cover the road. I observe a blackcrowned night heron along the edge of the water. My car sloshes through the overflow until I reach a small, rundown marina where a sign says, “Welcome to the southernmost point in Louisiana.” I find a spot beyond the fish-scaling table covered with old screws and rusted bolts, between some weeds, paint cans, and a midden of empty Bud Lights. I set up my lawn chair and telescope at the very tip of the land, the southernmost of the southernmost, and rest my now-cold coffee on an upside-down white plastic bucket.

It’s still half-dark, but I can make out a partially sunken tugboat that looks like it never recovered from Katrina, and the birds, of course, which are suddenly everywhere as the sky lightens. A green heron hunts from the dock, a half dozen more white ibises skirt an oily puddle, and egrets, splashes of white, dot the trees.

This is ground zero for the spill, or at least about as close as you can get to ground zero on the mainland. The oil is spewing some fifty miles across the water from where I stand. Yesterday, on the drive down from New Orleans, I pulled over and parked next to the water and called Rocky, my contact for the environmental magazine I am on assignment for, and explained that I wanted, needed, to get out on a boat. He replied calmly, “I can probably get you out on a boat tomorrow or the day after.” He did not understand. My world was not calm. Things were crackling in my head and I needed to seize the moment. I needed to get out on the water immediately. I tried to explain this. Though he still didn’t seem to get it, he gave up the name of a local charter fisherman.

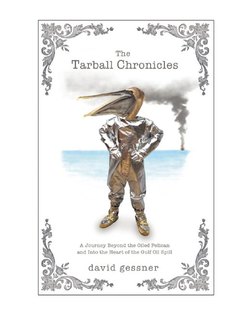

Captain Sal’s line was busy but when I finally got through he agreed to take me out for a short ride, warning that some thunderstorms were coming in. Half an hour later we were pulling out of the Myrtle Grove Marina and down a canal in the bayou, heading toward the Gulf. As we flew across the water I saw my first oiled pelican. It was black and flapped heavily in front of our boat.

“There are too many rules about the oil,” Sal said, shaking his head. “We were out looking for birds and we saw a pelican sitting on some boom and we pulled up to him and the guy I was with grabbed him. If the bird had got over the boom he would have died. He was too oiled up. So we get him in the boat and then we call the hotline for the oiled animals. The girl on the phone says: ‘What’s your nearest cross street?’ And we say we ain’t near any streets—we’re on the water. And she says ‘Well, what’s the closest restaurant nearby?’ Well, I say, there are no restaurants—we’re on the water. So finally we get hold of the wildlife rescue people. They come up in their boat and meet us out on the water. We reach the bird out of the tank where we’d put it and they say ‘Whoa, whoa, don’t touch the bird.’ They put their white space suits on and their masks before taking the bird. All the while the poor bird is suffering. So we say ‘Hurry up. You don’t need the suits—just wash your hands after.’ And they tell us that if any of us are caught handling the bird the authorities could shut down our whole operation and fine us. They would rather have the bird escape and die than get in trouble for helping the bird.”

After a while, Sal and I made our way to the outer fringes of marsh. It was there that the oil first struck in large quantities, the great wave of it darkening the fringes of this immensely green and vital landscape, turning it into something dark and necrotic. What I saw was black and burnt, to the point where, if I hadn’t known better, I would have thought it was the result of a small forest fire. The place looked devastated.

“Erosion is what is killing us here,” said Sal, pointing at the black fringe. “And when the oil hit we got about five years of erosion in one night.”

It wasn’t a pleasant sight, but it was good to see with my own eyes. Even before the oil started to gush, I had started to connect the dots between our need to consume and our intensified storms; between our rising water and our use of fossil fuels; between the destruction of the wild places we love and our hunger to exploit the energy in those places. I am not alone in making these connections, of course. We are all vaguely aware that our gluttonous ways are unsustainable, but we’ve also got our lives to live, thank you very much. And yet. There, staring at the burnt marsh, it was harder to pretend that everything was hunky-dory, harder to pretend that we can skip through our lives with no consequences. There, staring right back at me, was the dark result of our choices.

I am not that hopeful about our ability to change. But this is not about hope. It is about looking a thing in the eye. It is about keeping an honest ledger sheet. It is about adding up what is lost and what is gained. Are we so desperately hungry for this one particular type of fuel that we are willing to sacrifice our beautiful places, our homes, in a desperate attempt to slurp up what is left? Maybe the answer is yes. But if it is, we can at least do the math with open eyes. What are we getting and what are we giving up? If this is really our national sacrifice zone, then we had better figure out just who or what is being sacrificed and who is doing the sacrificing. Sacrifice is tricky word, and as a verb, it cuts both ways. It’s also a broad word and many things, from paying more for twisty lightbulbs to sacrificing an Aztec virgin, fit under its tent. So far it has also been an ineffective word, with most of us turning our backs on the notion that anything really has to change.

We are all happy enough with the idea of sacrificing as long as that doesn’t involve sacrificing anything ourselves. But at some level we all know something has to give. Know it but don’t want to see it. Maybe the first step is seeing honestly, which means at least owning up to what is really happening. Looking it in the eye. The good thing about being here is that I can’t help but face it now.

Captain Sal pointed at the feeble signs of defense against the oil. The boom looked like a child’s flotation device, the pool noodles my daughter uses, only hundreds of them lined up. If they looked frivolous, their job was not: to corral and keep oil out of fragile wetland ecosystems. Lately they had been trying out a special white absorbent boom, which, Sal told me, was locally called “tampon boom.” It floated ten yards from the grasses, while the newest brainstorm, boom-like cheerleader pom-poms, had been spread over one marsh island, apparently with the hope that the many cotton tentacles of the pom-poms would absorb better than the single-limbed boom.

“When the oil first came in it was the viscosity of peanut butter,” Sal said.

It was still possible to see its effects—most obviously the burnt look along the marsh edges—but we saw no actual oil. Sal thought this was due to the dispersants.

“They must have upped the nightly dosage,” he said, shaking his head. “We won’t know the real effects of this for years.”

Still, it was beautiful out on the water. Storms were coming—we could see them both on the GPS and with our own eyes—and a pink hue lit up the sky where a fingernail clipping of a moon hung. The undersides of the high clouds burned a reddish pink and when the lightning hit the whole sky turned electric. Despite the brewing storms, Sal said this was his favorite time to be out on the water, and I agreed. But he decided to head back in when he saw a waterspout—a small watery tornado that rose up out of the ocean—to the east. It looked quite beautiful but could reduce the boat to splinters in seconds.

“That’s nothing to play around with,” he said.

I noticed that the clouds on both sides of us had darkened.

“Are we between those two different storm clusters?” I asked.

“Actually about five,” he said, gesturing down at the GPS. He pointed to a particularly large cluster. “And that one’s chasing our ass.”

Though we did our best to outrun the one behind us and skirt the others, the skies opened when we were about halfway back, leaving us soaked through.

As of this morning, the Deepwater Horizon rig has been gushing for seventy-seven days, filling the waters in front of me. Some think of the Gulf as our least coast, the place where we dump all our shit. That shit includes hundreds of other leaky wells, as well as nutrients, waste, and fertilizers that are carried down rivers from Midwestern farms and emptied in its waters. No matter how we try to dress it up, it’s an afterthought, a dumping ground, the country’s toilet where we flush our waste. Now added to the mix are, at most recent count, about forty million barrels of oil and millions of gallons of dispersant. The president just called this the “worst environmental disaster America has ever faced.”

And yet, if the Gulf is a hell of sorts, it’s a beautiful hell. I walk up the road and stare out at three cypress trees that must hold a couple hundred roosting ibises, all of them settling and fidgeting, settling and fidgeting, like fussy sleepers. Beyond the ibises, I catch sight of a roseate spoonbill, an anomalous patch of bruised pink in a green cypress.

I am here to see what is left, and part of what is left is beauty. I need to be honest about that too. I have grown weary of avoiding things; it takes a lot of energy. Bring on the beauty and the ugliness both. Show me the honest math. What are we losing? What is being gained?

The birds have already lit up the trees, and now the orange ball lights up all of it, the world greening as it brightens. There is a vibrancy here that reminds me of a word I learned from a former chiclero, a Belizean man who helped find and tap rubber trees. “Yax” is a Maya word meant to describe a particularly vibrant and wild green. Here there is yax aplenty, from the cypresses to the marsh grasses and ferns to what I take to be some sort of elder plant. In counterpoint stands the rising sun. Despite what must be considerable pressure to sell out, it still rises freely, brandishing its usual blazing reds and oranges, not yet willing to don the corporate colors of green and yellow. It is nice to know that there are still a few realms beyond the reach of British Petroleum.

I sip my cold coffee in salute to the sunrise.