Читать книгу Postcards from Stanland - David H. Mould - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

I wrote my first travel journal at the age of nine. It had a circulation of precisely three—my father, mother, and sister. I’m not sure they actually read it, although they encouraged me to keep writing. It was run-of-the-mill stuff, a prosaic accounting of towns and sights visited, meals eaten, weather, and beach conditions—the predictable literary output of a nine-year-old. However, I would not have written anything, or asked my father to have my notes typed (with carbon copies), if I had not had the opportunity to travel.

In Britain in the 1950s and 1960s, most middle-class families took a summer vacation at the seaside, hoping the sun would peep through the clouds. Usually it did not. I have memories of cold, rain-swept South Coast resorts, with families huddled in their cars, the parents drinking tea from a thermos and reading the tabloids, glancing occasionally at the grey skies and the cold waves crashing on the stony beach. The children fidgeted and fought in the back of the car. There were no handheld gadgets to distract them; after they got bored with their toys, there wasn’t much else to do but start destroying the upholstery or tormenting the family dog, if it was unlucky enough to be on the trip. Occasionally, a parent would say: “Children, we’re at the seaside. Aren’t we all having a lovely time?” No one was, but no one wanted to admit it. On rare sunny days, the kids could play on the beach, perhaps even finding a patch of sand, but most days it was too cold to swim; the main seaside attractions were the funfairs on the piers.

Most years my parents headed for France or Spain, where the weather was predictably better. We strapped the family tent—a heavy, complicated canvas affair with many poles, pegs, and guy ropes, which looked as if it had been salvaged from a M*A*S*H unit—onto the roof rack of the Vauxhall Velox, and set off for Dover to take the ferry across the English Channel to Calais or Boulogne. We drove south, buying baguettes, butter, cheese, and tomatoes for picnic lunches and camping every night, my parents enjoying a bottle of vin ordinaire over dinner. I sat in the backseat, noting the kilometer posts, the terrain, and the historic landmarks, and taking notes. “Rouen,” I earnestly remarked, “has a large cathedral.” I helped navigate, a serious responsibility in the days before France built its equivalent of a motorway or interstate highway system. I was fascinated by the road maps and the names of towns, villages, and rivers, and I loved to plot our route. Often I enjoyed the trip—reading maps, getting lost, and asking for directions in shockingly bad schoolboy French—more than the destination.

I made my first solo trip at the age of seventeen, spending three months at student work camps in France, hitchhiking across the country and religiously writing postcards home. Unlike the typical “Weather lovely, wine cheap, pate de foie gras gave me indigestion, wish you were here” greeting, my postcards were crammed with details of my observations, now more insightful than “Rouen has a large cathedral.” I bought cards with the largest possible writing space, and usually managed to cram more than one hundred words into the left-hand side. Over the next decade, traveling with my then-wife, Claire, through France, Spain, Portugal, Italy, Switzerland, Germany, Greece, Turkey, and Morocco, I wrote many more postcards. Looking back, I wish I had sent some to myself because they were the only records of our trips to Fez and Marrakech (where I picked up both a full-length Berber djellabah and head lice) or of lingering too long on a Greek island, missing the bus at Thessaloniki and having to hitchhike the 1,250 miles back to Ostend on the Channel.

In the early 1970s, I worked as a newspaper reporter for the Evening Post, a large-circulation daily in Leeds, the main industrial and commercial center in West Yorkshire. My work travel was largely confined to mining and textile towns, with two trips to Northern Ireland, not exactly a tourist destination in the 1970s. I wanted to write about what I’d seen in Southern Europe, but my editor wasn’t interested. People didn’t want to read about the Basque Country or the Bosphorus, he said. Perhaps I could write about bed-and-breakfasts in Scarborough or renting a cottage at Skegness? Neither was on my holiday list, so my dream of being a travel writer was stymied. In 1978, I moved to the United States for graduate school, and in 1980 took a faculty position at Ohio University. It would be another fifteen years, after my first trip to Central Asia in 1995, before I started travel writing again.

When I did, I had more to say about cathedrals or mining towns or railroads or architecture or just about everything I saw about me. Credit goes to my teacher, mentor, and friend Hubert Wilhelm who taught cultural and historical geography at Ohio University for thirty-five years. His courses and our later collaboration on three video documentaries on the settlement of Ohio taught me to ask questions about the landscape. Who settled the land, where did they come from, and why? Why were houses and barns built in distinctive styles? Why was the land divided in certain ways? How were towns aligned to transportation routes? Although Hubert’s research was on vernacular architecture and settlement patterns in the US Midwest, the techniques can be applied to any region. Without his inspiration, I would not be asking questions about Central Asia’s gerrymandered borders, Soviet public architecture, or the impact of Stalin’s mass deportations on the ethnic mix.

By the mid-1990s, I was looking for a new challenge. Drew McDaniel, a faculty colleague, asked if I would be willing to travel to Kyrgyzstan to set up a media training center in Osh, the main city in the south. Drew had been to Kyrgyzstan a few months earlier and said he found it fascinating to observe the changes in the country as it emerged from over seventy years of Soviet rule. I said I’d love to take the opportunity. I didn’t admit to Drew that I had no idea where Kyrgyzstan was.

Since the mid-1990s, I’ve traveled to Central Asia, mostly to Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, more than a dozen times to teach at universities, lead workshops for journalists and educators, consult with TV and radio stations, and conduct research. My visits have lasted from a couple of weeks to three months, with longer stints for Fulbright Fellowships—sixteen months in Kyrgyzstan in 1996–97 and six months in Kazakhstan in 2011. I’ve made three trips to Uzbekistan, and two to Tajikistan; unfortunately, I haven’t had the opportunity to visit Turkmenistan.

As I traveled, I made notes on everything from landscape, culture, history, politics, environment, media, and universities to the challenges of communicating and staying warm. Recording first impressions was important because what struck me as interesting on first encounter would, after a week or two, seem commonplace. Every week or so, I assembled the notes—recorded in a cheap tetrad (school exercise book) from the bazaar or, less systematically, on napkins, credit card receipts, ticket stubs, and pages ripped from airline magazines—and wrote a rambling e-mail letter to a growing circle of family, friends, and colleagues. These letters were the inspiration for this book; they documented what I experienced while the memories were still fresh. I’ve also written op-eds, essays, and features on Central Asia for the Christian Science Monitor, Times Higher Education, Transitions Online, the Montreal Review, and other print and online media, some of which are reproduced here, in whole or in part. The book also draws on research on journalism and media for academic papers. Thus it presents Central Asia from several perspectives, from the wide-angle views of geopolitics—the contest for political and economic power—to the close-ups of travel, work, eating, and shopping.

A note on spelling. Language is a sensitive issue in Central Asia, and there’s no way that I will satisfy everyone with my choices because we are dealing with three language groups: Russian is a Slavic language; Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Turkmen, and Uzbek are Turkic languages; and Tajik is a Farsi (Persian) language. When a word or person’s name has a clear origin, I use a transliterated spelling that approximates how it would sound in the original language. For example, my friend Asqat Yerkimbay prefers to use “q” in his name because it is closest to the guttural “қ” sound in Kazakh; the Russian spelling of his name is “Askhat” with the “kh” a transliteration of the consonant “x” which does not exist in English or Kazakh. However, to apply that principle to the name of the country, Қазақстан, and people, Қазақ, gives you Qazaqstan and Qazaq, names that might confuse some readers. In this instance, I sacrifice consistency and correctness for convention, while noting that the “kh” was a colonial convenience, used by the Russians to distinguish the Казах of the steppe from the similar-sounding Cossack people. I use Russian names for places such as Karaganda (Kazakh—Qaragandhy) and Kostanai (Qostanay), simply because the Russian spelling remains widely used. There’s less linguistic confusion in Kyrgyzstan, where most places have Kyrgyz names.

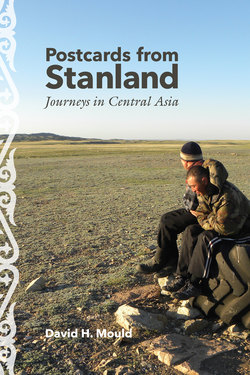

This book, combining personal experience, interviews, and research, is not intended as a travel guide. It’s not an academic study or the kind of analysis produced by policy wonks, although it offers background and insights. Think of it as a series of scenes or maybe oversized postcards (with space for one thousand rather than one hundred words) that I might have sent to friends and family if the postal system in Central Asia had been reliable enough. They feature observations of places and people, digging into an often complex and troubled past and, on occasions, offering an educated guess on the future. Postcards to ponder.

Charleston, West Virginia, November 2014