Читать книгу The Light in the Mirror - David I. Lane - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4

Dividing of Time

Ouch!” Richard bellowed as he danced around on one foot. Clad only in a sock, his other foot had come down hard on a nailhead protruding from one of the old porch floorboards.

“I guess city boys are supposed to wear shoes,” he muttered to himself.

As the pain subsided, Richard eased himself into the Adirondack chair that stood guard, and planted his feet on the railing, and sipped the coffee from the mug he’d placed on the chair arm. He watched a gray squirrel dig at the base of the 40-foot slippery elm that dominated the front yard. The early-morning sunshine—making amends for yesterday’s rain—promised a beautiful day.

“It’s gude to see ye relaxin’ and takin’ time to appreciate God’s creatures, laddie,” said Mac, making an appearance on the porch.

Richard glanced up, smiling, “Uncle, do you have squirrels in Scotland?”

Richard didn’t see the mischievous smile flicker across his uncle’s face. “No, no squirrels in Scotland are awaitin’ my return. But the countryside has plenty o’ them.”

Richard, used to Mac’s teasing, chuckled at the thought of his uncle keeping squirrels in Scotland. “I thought the Scots raised squirrels to save money on food.” In spite of Mac’s innate generosity, Richard liked to kid his uncle about Scots being thrifty.

“What a scunner!” snorted Mac in a tone of pretended disgust. “I’ll have ye know that Scots make better use o’ squirrels than that. We train them to go up in trees and gather nuts by the bushel. It’s an amazin’ sight to watch these creatures puttin’ choice nuts into a sack tied to their necks. And when they get too old to climb, the Scots teach them to sweep porches and walkways with their tails.”

Richard laughed and shook his head in acknowledgement of Mac’s superior “gift o’ the gab.” When Mac failed to embroider his story, as he customarily did, Richard turned in his chair to look at him. He saw that his uncle was staring at the neighbor’s yard across the street.

“Those poor roses over there,” said Mac sadly. “Mr. Galiger simply doesn’t know the first thing aboot roses. He prunes them as if he’s prunin’ a mulberry bush.”

“How should he prune them, Uncle?”

“With roses, ye must prune from the inside out, so that the plant grows up and out.” Mac extended his arms outward above his head to describe this desirable growth. “He prunes from the outside in, and cuts branches too far above the joint; he leaves stumps where disease and bugs can attack the plant.”

“Why don’t you tell Mr. Galiger how to prune? He can see how good your roses look.”

“Di’ ye think my head buttons up at the back, laddie?” Mac patted the back of his head. “I canna think o’ a better way o’ upsettin’ a neighbor than to tell him how to grow his roses. No. I must be patient and wait ‘til he asks my help, which I would gladly give.”

“When do you think Mr. Galiger will come to you for help?” Richard couldn’t picture their neighbor, who was always in a hurry, taking time to learn how to tend his roses.

“Well, my boy, when the time is right. Remember, ‘To everythin’ there is a season, and a time to every purpose under heaven,’ includin’, ‘a time to keep silent and a time to speak.’ It’s natural when ye’re young, laddie, to want to hurry time; waitin’ becomes painful. And when ye’re older, ye want to slow time doon, and waitin’ then has a meanin’ o’ its own.”

“Well, yes, it’s true, Uncle. I hate waiting to do something. I mean if it’s something that needs doing, I want to do it now. Speaking about time reminds me, I need to start looking for a summer job. After all, I’m not independently wealthy.”

“Ye may not be ‘independently wealthy,’ but your folks’ estate has enough left to pay your way through graduate school. In the meantime, ye don’t have to worry aboot expenses. I’ve enough money for both o’ us. Say, why don’t ye do somethin’ for fun today and maybe later we can watch a video or play some draughts.”

“Draughts? Oh, you mean checkers. Sure. Maybe if we played more often I’d remember. Why don’t Scottish people just say checkers?”

“I can tell ye, the Scots wonder why Americans don’t just say draughts.”

“Touché! My old professor Hans Leitner would call my comment ethnocentric. But he doesn’t need to learn to say draughts.”

Further inactivity encouraged by his uncle, Richard followed the Scot back into the house, careful to avoid the offending nail. Going to his room, Richard selected a book from the well-filled bookcase. He’d purchased The Eternal Path a month ago for a time of leisure like the present. The book gave a fictional account of the fight to return prayer to public schools. On the way back to the porch, he grabbed a sofa pillow to make the wooden patio chair more comfortable.

Later, Mac insisted that Richard continue reading while he prepared lunch—coffee and sandwiches, with ice cream for dessert—which they ate together on the porch.

“Thanks for the lunch, Uncle. You can’t beat cheese on rye. Say, you know Brent, my friend from the university? He lent me a movie weeks ago. I really should watch it and return it. Would you like to see it? It’s called The Time Machine—a science fiction film, made in 1960, the box says.”

“Let me tidy up the kitchen a wee bit and we’ll see what Hollywood did with H.G. Wells’ story.”

“Oh, have you read the book?”

“Yes, laddie. It was Wells’ first novel, and it brought him instant success. Published in 1895, I think. Wells was wise to make one o’ his characters, David Philbey, a Scotsman. This character personifies one o’ the traits o’ true friendship, loyalty. After The Time Machine, he wrote more books, at least 100. But the more interestin’ ones predicted future scientific inventions that seemed to materialize.”

“What did Wells ever predict that came true, Uncle?”

“Ye can decide that for yourself. Read his book The War o’ the Worlds, which he wrote in 1898 and see if he correctly envisioned modern warfare.”

“How do you know so much about H. G. Wells?”

“Ye forget, I spent a gude part o’ my life in libraries, as a librarian and as a lover o’ books.”

While Mac put things away in the kitchen, Richard found the video and waited for his uncle. When Mac finally appeared, he was carrying a big bowl of fresh popcorn.

“Show time!” announced Richard, as he inserted a cassette into the VCR. Then he sat on the floor, close to the popcorn.

The film began silently, showing dark, eerie images of various timepieces. A sundial appeared out of the darkness. Then small clocks came into view, followed by larger clocks. Finally, came the largest clock of them all, Big Ben. The chimes of the great London clock coincided with the onset of thunder and lightning, which seemed to carry an ominous warning. Then orchestral theme music filled the room, as credits flashed across the screen.

Richard and Mac both became engrossed in the movie; it combined romance and adventure in the typical Wells’ fashion. The main character, George, time-traveled into the remote future and returned to tell his housekeeper and four friends what he’d discovered. Centuries into the future, he found a very different Earth from the one he left behind. Decades of war had devastated the planet. Two races of human beings emerged, one living above ground and the other below ground. George described the above-ground beings, the Eloi, as handsome, docile, and ignorant, and the below-ground beings, the Morlocks, as monstrous, aggressive, and ignorant. The Morlocks controlled and preyed on the Eloi. George told his friends how he had taught the Eloi to defend themselves against the Morlocks. At the close of the film, George indicated his intention to return to the future to help the Eloi to rediscover the noble ideas and truths of the past that had made humanity humane.

Richard wondered. If H. G. Wells could view our present world, would he see the beginnings of the fictional world of the future he’d imagined? The last scene of the film left him pondering the possibility of time travel. Yesterday’s science fiction often becomes tomorrow’s scientific truth. But time travel? Not even Einstein’s space-time continuum made that sound possible.

“Uncle Mac, do you think we will ever be able to travel in time?

“My boy, we can travel in time now. Our memory can take us into the past and we can see how it affects the present. And we can ride our imagination into the future, and see what consequences might follow our actions. But it takes more courage for that kind o’ time travel than the kind H. G. Wells had in mind. For it isn’t the Morlocks we must face, it’s ourselves.”

Mac’s unexpected response drew Richard into a thoughtful silence.

“I enjoyed The Time Machine! It was a braw film, so it was. I thank ye for showin’ it to me.”

“I’m glad you liked it. Do you think the film did justice to the book?”

The Scot cocked his head in silence and stared thoughtfully into space in a familiar look of contemplation.

“I must say this was one film that tried to bring the book to life. Indeed, it did do justice to Wells’ story!”

“Uncle, since we’ll soon begin a new millennium, do you think God will do something amazing to show His power?”

Mac’s eyes twinkled. “We mortals seem to think that God has adopted our calendar and marks off the centuries as we do. Wait a minute, my boy.”

Mac left the room, returning in a couple of minutes with a book.

“Here, let me read somethin’ to ye in Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain.” Mac paged through the book quickly, searching. “I have it now. Listen: ‘Time has no divisions to mark its passage; there is never a thunderstorm or blare o’ trumpets to announce the beginning o’ a new month or year. Even when a new century begins it is only we mortals who ring bells and fire off pistols.’”

“That’s an interesting quote. It makes me think.”

“What does it make ye think?”

“That we humans suppose we can slow time by dividing it. I don’t know. Maybe I’ll read that book.”

“Ye might enjoy it. But, back to your question. Ye can be sure that the new millennium is part o’ God’s plan, and He has miracles in store, as He does today. Ye must remember, too, a thousand years is but a wink o’ the eye to God. Now, I’m goin’ to take a wee kip before supper.”

“Oh sure, Uncle. Have a nice nap. I’ll go back to my book, and keep things quiet.”

A week later, Richard announced, “I have an e-mail for you, Uncle, from someone by the name of MacPherson, James MacPherson. That’s certainly a Scottish name.”

“Ye have that right, laddie. He lives in Dumbarton, Scotland, on the banks of the River Clyde. I’ve known Jamey since he was a wee bairn. He’s a pure soul, he is. I saw him a few years ago durin’ my last visit to Scotland. But he likes to take the mickey.”

“You mean he drinks a lot?”

“No!” Mac chuckled at how his nephew had misinterpreted the Glasgow expression. “I mean he likes to tease and make fun o’ his friends to make them laugh.”

“Sounds like someone I know. Here, I printed his message..” Richard handed the page to his uncle.

Mac quickly read. “Soonds like Jamey awright. He asks, since I’ve stopped policin’ book-borrowers, what have I been doin’ with my life? He suggests that I should come to Dumbarton to help him with his shippin’ business. He operates out o’ the Port o’ Glasgow. He says he has plenty o’ men with strong backs and strong minds, but he needs a man with a strong conscience to be sure that profits don’t exceed ethics. They’re shippin’ Scottish gudes all over the world in days, when it used to take weeks.”

Richard smiled and shook his head. “Goods, people and information are moving faster and faster, but never fast enough to satisfy us. We expect to travel hundreds of miles in minutes.”

“Aye. We want everythin’, includin’ ourselves, to arrive yesterday. We’ve lost the ability to appreciate the wait between wantin’ somethin’ and gettin’ it. Why, when Thomas Jefferson became president in 1801, Americans couldn’t move gudes and information much faster than the ancient Romans. And probably most people expected it to remain that way. In Jefferson’s day, it took aboot six weeks for information to go from the Mississippi River to Washington, D.C. When Abraham Lincoln took office aboot sixty years later, a telegraph could convey information nearly instantaneously. Now look, e-mail from Scotland, like that!” Mac snapped his fingers. “The more we compress time, the more we shrink space. Whatever happens, happens faster and closer.”

“Is that bad, Uncle?”

“Aye, in some ways. It’s like a ride in a lift . . . an elevator. Ye go up so fast, ye feel ye’ve left your stomach behind. We may move so fast that we leave behind somethin’ we need and value, and then we won’t have much reason to get to where we’re goin’.”

“Do you think it’s inevitable, that we won’t be able to help ourselves?”

“No, my boy. Earthly time alone needn’t mark the movements in your life. Ye should also give thought to where ye are in God’s time. No matter how fast life may seem to move ye along laddie, God remains the same yesterday, today, and tomorrow.”

Both men sat silent for a few minutes. Each man used the silence to reflect on those ancient words.

“I guess I don’t understand what you mean by ‘God’s time,’ Uncle. In a way I do, but . . .”

“Richard, I believe the Bible teaches that God expects His children, day by day, to grow in spirit, as they develop physically. But, if Christians focus only on material things—how many pounds, dollars, or honors they’ve gained or lost—their spirits won’t develop, and God’s timetable for them will be disrupted. Then, God may put somethin’ in their way to slow them doon, so they can see what’s important in life.”

“Oh yes, I see.” Richard nodded to encourage him to continue.

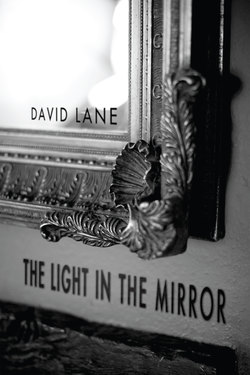

“The Scriptures are plain: ‘When I was a child, I used to speak as a child, think as a child, reason as a child; when I became a man, I did away with childish things.’ When we’re in God’s time, laddie, we see and hear what He tells us, and, in His time, we come to understand who we are, spiritually, and how we’re to use our gifts in His divine plan. ‘For now we see in a mirror dimly, but then face to face; now I know in part, but then I shall know fully just as I also have been fully known.’ Sometimes, God uses our experience to shine a light in the mirror. Then we see more clearly what He would have us know.”

Often in the days to come, Richard would contemplate the verses from I Corinthians that his uncle had quoted.