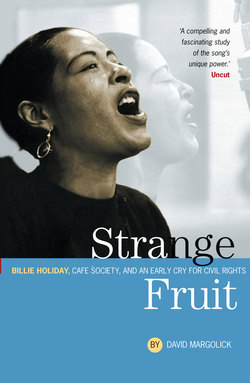

Читать книгу Strange Fruit: Billie Holiday, Café Society And An Early Cry For Civil Rights - David Margolick - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеI wrote “Strange Fruit”

I wrote “Strange Fruit” because I hate lynching and I hate injustice and I hate the people who perpetuate it.

—Abel Meeropol, 1971

THE OPENING LINE of Holiday's autobiography, Lady Sings the Blues, famously reads: “Mom and Pop were just a couple of kids when they got married. He was eighteen, she was sixteen, and I was three.” Like so much in the book, this is not quite right; in fact, things were worse: Holiday's parents never married and were scarcely together at all, except at the carnival (or dance) in Baltimore on the night in the fall of 1914 when she was conceived.

Holiday was born in Philadelphia on April 7, 1915. That made her only twenty-four years old in 1939, but she had already experienced enough prejudice and despair by then—including time in a home for wayward black children, then in a whorehouse, where she first heard the recordings of Bessie Smith and Louis Armstrong—to call herself a “race woman.” She began performing in Harlem in the late 1920s; by l933, she had been discovered by the great record producer John Hammond, who quickly teamed her up with Benny Goodman, Teddy Wilson, and other legendary musicians of the day. Together, they made what became some of Holiday's finest and most beloved records: “I Wished on a Moon,” “What a Little Moonlight Will Do,” and “Me, Myself and I,” to cite just three examples. In the late 1930s, she toured with the bands of Count Basie and Artie Shaw.

Though all of the hard knocks helped Holiday infuse a unique mixture of resilience, defiance, exuberance, and shrewdness into everything she sang, her songs, at least on paper, were invariably what her first biographer, Linda Kuehl, called “second cousins to her favorite reading: love comics and true romance magazines”—that is, bland, banal ballads. Politics, and particularly racial politics, had never influenced her choice of material until “Strange Fruit” came along.

Holiday's “autobiography”—cowritten by Dufty and entitled Lady SingsThe Blues (the publisher insisted that “blues” be in the title, though Holiday herself had favored the last two words of “Strange Fruit:” “bitter crop”)—offers an account of the songs origins that may set a new record for most misinformation per column inch. (Holiday later tried to fob off the blame on Dufty: “Shit, man, I ain't never read that book,” she said. In fact, because her publisher was skittish about the entire undertaking, it made her read and sign every page of the manuscript. The embellishment was actually all Holiday's; she had been peddling much of the mythology for years. In fact, she told much of what appears in her autobiography to a Los Angeles newspaper columnist only three years after she introduced “Strange Fruit.”) “The germ of the song was in a poem by Lewis Allen [sic],” Holiday declared in the book. “When he showed me that poem, I dug it right off. It seemed to spell out all the things that had killed Pop.”

As Holiday told the story, her father, a musician in Fletcher Henderson's band, was exposed to poison gas as a soldier during World War I and died of pneumonia in 1937 after several segregated Southern hospitals refused to treat him. “Allen had heard how Pop died and of course was interested in my singing. He suggested that Sonny White, who had been my accompanist, and I turn it into music. So the three of us got together and did the job in about three weeks.” (To the Los Angeles newspaperman, she had Meeropol coming into Cafe Society, and realizing upon hearing Holiday that were his anti-lynching poem set to music, she'd be “the one person in the whole entertainment world who could sing it.”)

Meeropol told a very different story. An English teacher at DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx for twenty-seven years, he had led two other, parallel lives. One was as a political activist: he and his wife were closet Communists, donating a percentage of their earnings to the Party (the FBI maintained that he had belonged only until 1947, though it continued to follow him for twenty-three years after that). The other was as a writer, poet, and composer. Meeropol had what Earl Robinson, the man who wrote “Ballad for Americans” and “Joe Hill,” called “an inexhaustible ability to turn out topical lyrics.” He wrote incessantly—poems, ballads, musicals, plays—all using the nom de plume “Lewis Allan,” the names of his two natural-born children, neither of whom survived infancy. Many of his creations were political, albeit with a light touch: representative song titles include “Swing Away with Daladier,” “The Chamberlain Crawl,” and “Is There a Red Under Your Bed?” Though he had his admirers—Ira Gershwin, the German-American composer Kurt Weill (“his lyrics have great beauty and a quality of their own... I consider him a highly talented writer, a very conscientious worker, and a man of great integrity and high ideals”), and the Nobel Prize-winning novelist Thomas Mann wrote references for him when he applied for a Guggenheim Fellowship in the 1940s— most of his work was quickly forgotten and now sits in dusty heaps at Boston University. Apart from “Strange Fruit,” he is best known for the lyrics to “The House I Live In” (a paean to tolerance cowritten by Earl Robinson and sung by Frank Sinatra in a short film that won a special Oscar in 1945), “Beloved Comrade” (written in 1936 for the Spanish Loyalists and often sung in tributes to Franklin Roosevelt, who is said to have liked it), and “Apples, Peaches, and Cherries”(once recorded by Peggy Lee).

Lynchings—during which blacks were murdered with unspeakable brutality, often in a carnival-like atmosphere and then, with the acquiescence if not the complicity of local authorities, hung from trees for all to see—were rampant in the South following the Civil War and for many years thereafter. According to figures kept by the Tuskegee Institute—conservative figures—between 1889 and 1940, 3,833 people were lynched; ninety percent of them were murdered in the South, and four-fifths of them were black. Lynchings tended to occur in poor, small towns—often taking the place, the famed newspaper columnist H. L. Mencken once said, “of the merry-go-round, the theatre, the symphony orchestra.” They involved either the whole community or a cabal of vigilantes, often in disguise. And they were meted out for a host of alleged offenses—not just murder, theft, and rape, but for insulting a white person, boasting, swearing, or buying a car. In some instances, there was no infraction at all; it was just time to remind “uppity” blacks to stay in their place.

The numbers gradually declined; by the 1930s the days were long gone when the pioneering black civil rights leader W. E. B. Du Bois unfurled a banner declaring “Another Lynching Today” outside his New York office whenever one occurred. Officially, there were only three lynchings in 1939—the year Holiday first sang about them. (There were nonetheless signs that many more than that occurred but were hushed up, and that they were increasingly brutal and sadistic. “They used to be big mobs hunting for a nigger, but now you just hear about some nigger found hanging off a bridge,” one observer reported.) Still, a survey taken in 1939 revealed that more than six in ten Southerners thought lynchings to be justified in cases of sexual assault. And despite a long campaign by the NAACP, Congress had never managed to pass a federal anti-lynching law.

Lynchings may have been localized affairs, but as Gunnar Myrdal pointed out in An American Dilemma, his classic 1944 study of race relations in the United States, they brutalized feelings everywhere. “Even in the North, some people have ceased to be concerned when another lynching occurs, and they jest about going South to see a lynching,” he wrote. Meeropol, clearly, was not among them. In fact, it is possible that what inspired him to write “Strange Fruit” was a double lynching that took place north of the Mason Dixon line—in Marion, Indiana in 1930—immortalized in a shocking and widely publicized photograph. In any case, it was around that time that Meeropol, then in his early thirties, came across in a civil rights magazine a photograph of a particularly ghastly lynching, and he said it had haunted him for days. So he wrote a poem about it, one that the Communist journal The New Masses agreed in early 1936 to publish but that first saw print—as “Bitter Fruit”—in the January 1937 issue of The New York Teacher, a union publication.

Meeropol often asked others, most notably Earl Robinson, to set his poems to music. But with “Strange Fruit,” he insisted on doing the task himself. The song was then performed regularly in left-wing circles—by Meeropol's wife, by progressive friends at gatherings in hotels and bungalow colonies around New York, by members of the local teachers union, by a black vocalist named Laura Duncan (including once at Madison Square Garden), and by a quartet of black singers at a fund-raiser for the anti-Fascists during the Spanish Civil War. As it happened, the co-producer of that fund-raiser, Robert Gordon, was also directing the first floor show at Café Society, which had opened in December 1938. The featured attraction: Billie Holiday, who had just quit Artie Shaw's band in part because she'd been forced to take the freight elevator during a gig at a New York hotel. And not just any hotel, but one named after Abraham Lincoln.