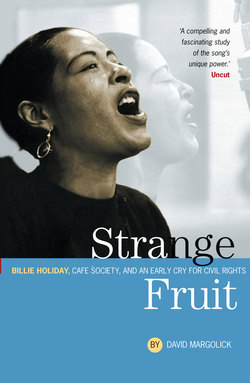

Читать книгу Strange Fruit: Billie Holiday, Café Society And An Early Cry For Civil Rights - David Margolick - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеForeword

THERE APPEARS, in this valuable study about a significant moment in American popular music, American social life, and the distinctly American voice and presence of Miss Billie Holiday, an alarming bit of reporting. I'm trying to remember where this terrible thought first appears, so as to spare you the shock of it, but I don't want to look it up again; I found it painful enough to read the first time. I'm almost certain that it can be found twice in David Margolick's informative book, which is a large window into a small, albeit influential, world. What I'm referring to is a remark made by someone who knew Holiday. Margolick's source says something about Holiday's intelligence, pointing out that Billie Holiday, the star, did not read much in the way of “real” literature, did not have a large vocabulary, and had a fan's love of cheap romance stories about men and women who ended up on the sunny side of the street with no intimation of despair or death darkening their kisses, stories that espoused none of the terror or sarcasm or knowledge of slow death by injection with which Holiday herself infused even the happiest of her tunes, this potential candidate, we are given to understand, for Literacy Partners.

It's disgraceful—the very idea that Billie Holiday knew less than us because she reveled in what some would consider lowbrow entertainment, just as jazz was, in its time, considered lowbrow entertainment. That Holiday's preferred reading matter should be considered a reflection of her “true” self—have we not had enough of Holiday as the crude romantic primitive, a prisoner of bad lyrics, too fat or too slovenly or just too stupid to clear all those teary technicolor Modern Romance tomes off her dressing table? It's cruel, and often racist or sexist or both, to measure this definer and re-shaper of American jazz and popular singing by the mediocre standards we set for ourselves. But there we are. The Western keepers of the canon—our models of intelligence—still know so little about what makes up a Billie Holiday, let alone what makes her an authentic American female genius, a Titan in her output, that the question of her native intelligence is picked at like a scab by her detractors because she irritates them and their collective mind. Holiday makes no sense. She did not compromise her work. And she helped to create a world, a world where her voice would be at home, which is to say the world that David Margolick evokes in his seminal text about the end of NewYork's literal and figurative café society.

Café Society: The true home of the birth of cool, twenty years before Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker donned their berets and wind instruments. It was a place that contributed greatly to the idea and reality of a New York that was, and is no longer: a city—the romantic view—that did not demand so much compromise of its artists, a city that encouraged its inhabitants to search out the substance that could be found in the stylish affect of its artists, singing and playing, some of them, in the bars and clubs of Greenwich Village, home of Holiday's voice at Café Society during a certain period in a city that is no longer.

Billie Holiday's style: It has a kind of dopey optimism, doesn't it, a kind of twisted Puritanism, the way most Negro sounds—spoken or sung or written—do, since Negroes are America, a mixture of all that we consider American: a little black, a little white, a little Native American. Her slow drawn-out sound was the sound of her time: People then took time to listen to a story, and she could tell one. I'm not sure, but I think that the first time I heard Billie Holiday's singing was the first time I realized that a singer could approximate all the bullshit and beauty that goes into a love affair. When Billie Holiday sang, she was simultaneously the embodiment of the egotism of a love affair (“Look at me! Look at me!”) and a cool commentator on love's folly. And that is remarkable.

Remarkable, too, is the preservation of her myth, which Billie Holiday more than contributed to, and which David Margolick describes in his (at times) humorous and concise study. Certain questions Margolick puts to rest forever. Billie Holiday did not write “Strange Fruit,” as she claimed in her unreliable but immensely readable memoir, Lady Sings the Blues. But she made it her own. She had so few words she could call her own, you see. And since the song became her, and she became the song, who, technically, could be called the truer auteurof “Strange Fruit”? We remember her singing the song, and we don't remember the writer, Mr. Meeropol. What does that say about the way popularity eclipses the more private environs inhabited by the writer? Would “Strange Fruit” matter to us if Billie Holiday had not sung it at a particular time, in New York, and placed all those black bodies in our minds as a way of conveying something about herself, undoubtedly, this most impersonal of biographical artists? David Margolick is interested in such philosophical questioning, and so am I.

Billie Holiday helped write the words to a number of remarkable songs, such as “Fine and Mellow” and “God Bless the Child.” If you listen to them in a certain way, you'll see that they are the condensed, distinctly Negro and distinctly American version of those True Romance comics she read and re-read, looking for truth in something as deep and shallow as American pop, American language.

HILTON ALS

NEWYORK, NOVEMBER 1999