Читать книгу Indonesian New Guinea Adventure Guide - David Pickell - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

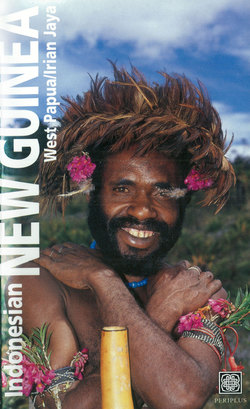

ОглавлениеTHE WEST PAPUANS

The Province's

Diverse

Ethnicities

Even today, members of groups unknown to the outside world occasionally step out of the forests of West Papua. The most populous groups of the highlands and the coasts have become rather worldly, and their languages and customs have been recorded by western and Indonesian anthropologists. But a vast area between the coasts and the mountains remains concealed by a canopy of thick vegetation, and little is known even of the topography of these areas.

As recently as 1996, two previously unknown groups surfaced. Representatives of the first, apparently shocked by what they saw, disappeared again immediately. Those of the other took the first tentative steps into the outside world, accepting modern medicine and steel axes. These latter tribesmen, sartorially distinguished by long, quill-like ornaments jutting straight up from holes in their nostrils, spoke an unknown language.

The West Papuans speak a bewildering 250 different languages. Many, perhaps most, are barely known outside their own ranks, and only a handful have been thoroughly studied by ethnographers. The best known are the Ekari of the Paniai Lakes region, one of the first places where the Dutch colonial administration seriously established an outpost, the Dani of the Baliem Valley, and the Asmat of the South Coast. The economies and customs of several other groups have been systematically recorded, and at least the basics of the languages of many others are known.

Any attempt to properly describe such a diverse group of people and cultures in such a limited space is bound to fail, so we will try to mention just the better-known groups, and to fit them into a classification according to geography and agricultural practices.

People of the coastal swamps

Although malarial, uncomfortably hot, and often thick and impenetrable, West Papua's lowland swamps are blessed with an abundance of sago palms, and nutritious game such as birds and seafood: fish, turtles, crabs, prawns and shellfish. The trunk of the sago palm provides an easily harvested staple, and the game the necessary protein.

Sago is collected, not farmed, and in areas where stands of the palm are widely dispersed, people lead a semi-nomadic life, living in "portable" villages. Large stands of sago and the rich waters at the mouths of major rivers can support populous, more or less stable villages of up to 1,000 inhabitants.

Sago collecting is the most efficient way to obtain starch. Although the tough palm must be chopped down, the bark removed, and the pith tediously pounded and rinsed (the glutinous starch must be washed from the woody pith), sago gathering requires far fewer man-hours than those required to grow, for example, paddy rice.

A Biak islander wearing a mantle of cassowary feathers. The people of Biak are of Austronesian descent.

The long, wide swamps of the South Coast support the Mimikans of the coastal area south of Puncak Jaya, the Asmat of the broad coastal plain centered around Agats, the Jaqai inland of Kimaam Island around Kepi, and the Marind-Anim around Merauke in the far southeast. Along the North Coast, the Waropen groups of the coastal swamps around the edge of Cenderawasih Bay and the mouth of the great Mamberamo River, live a similar lifestyle.

Of all these coastal people, the Asmat are the best known. Their fierce head-hunting culture, powerful art, and the unfortunate disappearance of Michael Rockefeller in the region in 1961 have succeeded in making them infamous. (See "The Asmat" page 146.)

Many of these coastal peoples were at least semi-nomadic, and their cultures revolved around a ritual cycle of headhunting. Nomadism and headhunting are, of course, high on the list of established governments' most loathed practices, and both have been banned and discouraged in West Papua.

The Mimikans, the Asmat and the Marind-Anim have all suffered from the loss of spiritual life that came about with the ban on headhunting. None of these groups is particularly suited culturally to organized education, business or any of the other limited opportunities that have come to them with modernization.

The Austronesians

Some of West Papua's coastal areas have been settled by Austronesians, and here garden and tree crops replace sago as staple foods. Particularly on the North Coast and the neighboring islands, many ethnic groups speak Austronesian languages that are very different from the Papuan languages found throughout the rest of the island.

The Austronesians have historically been involved in trade with the sultanate of Tidore, the Chinese, the Bugis and other groups from islands to the west. Bird of paradise skins and slaves were the principal exports, along with whatever nutmeg could be taken from the Fakfak area.

Austronesian influences can be seen in the raja leadership system practiced among these groups, perhaps adopted from the sultanates of Ternate, Tidore and Jailolo. With their political power cemented by control of trade, some rajas ruled wide areas embracing several ethnic groups, from seats of power in the Raja Empat Islands, in the Sorong area, around Fakfak or in the Kaimana region.

A somewhat different system was found in the Austronesian areas around Biak, Yapen, Wandaman Bay and east of Manokwari. Here some villagers practiced a system of hereditary rule, and others were ruled by self-made, charismatic leaders or great war heroes.

The inland groups

Inland from the coastal areas, in the foothills and valleys of West Papua, scattered groups live in small communities that subsist on small farms, pig raising and hunting and gathering. They usually grow taro and yams, with sweet potatoes being of secondary importance. Since they were intermediaries between the highland groups and the coastal people, some groups in this zone were important intermediaries in the trade in pigs and cowrie shells, both, until fairly recently, serving as "money" in the highlands.

In the interior of the Bird's Head, the Maibrat (or Ayamaru) and surrounding groups carried on a complex ritual trade involving kain timur—antique cloths from eastern Indonesia—which were obtained from the coastal Austronesian traders in exchange for pigs and food from the interior.

Every two years the Maibrat "Big Men" (shorthand for a kind of charismatic leader) organized a huge feast involving payments to relatives and economic transactions between groups. The Maibrat believed that death and illness were the work of ancestral spirits. Good relations among the living, achieved through gift-giving, were essential lest the ancestral spirits be angered.

A Dani woman, dressed in marriage finery. The Dani, like most of West Papua's highlanders, are Papuans.

The people living in West Papua's lowland forests between the coastal swamps and the highlands are the least known. Nowhere is there a very high population density, and many of these people are nomadic.

The Kombai, Korowai and scattered other groups living between the Asmat area in the south, and the southern ranges of the Central Highlands in the north, have proved to be among the most resistant people on the island to the entreaties of missionaries and others who would have them join the so-called modern world. One group has for years systematically rejected, with spears and arrows on occasion, missionaries, government workers, and even gifts of steel axes, nylon fish nets, and steel fishhooks.

Cannibalism is frequently reported and surely still practiced here. These unregenerate forest dwellers—inhabiting the area in the upper reaches of the Digul River watershed and scattered other locations in the foothill forests south of the central cordillera—live in tall tree houses, perhaps to escape the mosquitos, and the men wear leaf penis wrappers.

An Asmat man from Biwar Laut, on the south coast.

Highland West Papuans

People have been living in West Papua's highlands for 25,000 years, and farming the relatively rich soils here for perhaps 9,000 years. The altitude of the rugged mountain chain produces a more temperate climate than the south, and perhaps more important, is outside the worst of the range of the malarial Anopheles mosquito.

Highlanders practice pig husbandry and sweet potato farming. Sweet potato cultivation, featuring crop rotation, short fallow periods, raised mounds and irrigation canals, attains a peak of sophistication in the Baliem Valley. West Papua's first highlanders relied on taro and yams, adapting to the subsequent introduction of sugar cane, bananas, and much later, the sweet potato.

One sartorial trait distinguishes all of West Papua's highlanders: they all wear "phallocrypts" (penis coverings). Or at least all did, until this striking wardrobe caught the attention of some puritanical missionaries. However, there is less pressure on the highlanders to wear clothes today than there has been in the past, as both the Christians and the government have toned down their campaigns.

The well-known Dani are but one of many highland groups living in West Papua's highlands. (See "The Dani," page 110.) West of the Dani are the Amung, Damal and Uhundini group, numbering about 14,000 and sharing a language family. West of the Damal are the Moni, numbering about 25,000. (See "Growing up Moni," page 118). Further west, in the vicinity of the Paniai Lakes, the westernmost extent of the central mountains, are the Ekari, numbering about 100,000.

East and south of the Dani, living in some very rugged terrain, are the 30,000 Yali, speaking several dialects. Three related groups live east of the Yali: the Kimyal, some 20,000 of whom live around Korupun, the 9,000 Hmanggona who live around Nalca, and the 3,000 Mek or Eipomek who live around the village of Eipomek.

The Western Dani

The Western Dani, sometimes called Lani, live in the highlands from east of Ilaga to the edge of the Grand Baliem Valley. The introduction of the Irish potato, which can withstand frost and cold, has allowed the Western Dani to plant up to 3,000 meters.

The Western Dani have been responsive to the efforts of missionaries and the government, and have historically been far less warlike than their neighbors in the Baliem, as they farm far less fertile soil and consequently have less excess population and time to expend on warfare. The Baliem Dani's proclivity for warfare is considered to be a product of the spare time resulting from good soil and sophisticated agricultural techniques. (For more on the Baliem Valley Dani, see "The Dani," page 110.)

The Yali

The Yali live in the area west of the Baliem Valley, from Pass Valley in the north to Ninia in the south. There are at least three dialects of the Yali language, with speakers centered around Pass Valley, Angguruk and Ninia. The language is related to Dani, and their name comes from the Dani word "yali-mo," which means: "the lands to the east"

[Note: Many common West Papuans ethnic designations come from other groups, for the simple reason that many languages do not have a term for "we" or "us" that is not non-exclusive of members of other groups, or that refers to a group larger than the immediate political community or confederation. For example, the Dani have a word for "people," but this is in contrast to "ghost" or "spirit," and is not exclusive of any other people. The word "yali" has a cognate in the Yali language that also means "east," and the Yali will use it to refer to people living east of their territory. It is perhaps important to note also that this "east" is not a compass point per se; it really refers to a specific end of the common trade route, which, in this case, is east. Many of the terms coined by western anthropologists for ethnic identifications have gained currency among the highland West Papuans, through the bi-or tri-lingual guides around Wamena. For example, "koteka," an Ekari word for a penis gourd, is universally understood in the Baliem Valley, even though a Dani word (horim) exists. Some people call this bahasa baru, the "new language."]

The Yali are immediately distinguished by their dress, which consists of a kind of tunic constructed of numerous rattan hoops, with a long penis gourd sticking out from underneath. They maintain separate men's and ritual houses, which unlike Dani huts are sometimes painted with motifs reminiscent of Asmat art. The Yali are farmers, growing sweet potatoes and other highlands crops in walled gardens.

The terrain of Yali-mo is formidable, which delayed the arrival of both missionaries and the government. Though contacted in the late 1950s by the Brongersma Expedition, the first permanent outside presence was a Protestant mission established in the Yali-mo Valley in 1961.

When the first airstrip was built at the mission, one or two cowrie shells was still an acceptable daily wage and most of the Yali had only heard rumors of steel axes. The missionaries traded axes to acquire land and pigs, introducing the metal tool's widespread use. The Protestants began a school and offered medical aid including a cure for frambesia or yaws, a virulent rash caused by the spirochete Treponema pertenue. This disfiguring disease was eradicated in 1964.

Also in 1964, anthropologist Klaus Friedrich Koch arrived in Yali-mo, where he learned the language and conducted anthropological research that led to the book War and Peace in Jalemo. Like the Dani, the Yali are farmer-warriors, but they live in a much more hostile environment. The Yali responded eagerly to the mission-sponsored introduction of new plants such as peanuts, cabbage and maize, as well as to animal husbandry—placing great demands on the first imported stud hog.

By the time Koch left the field in 1966, there were already six landing strips in Yali-mo, opening this area to the outside world.

In 1974, a mission station established by the Netherlands Reformed Congregation was destroyed and all their Yali helpers were killed and eaten. The massacre was possibly the culmination of misunderstandings by the Nipsan people of the new cultures brought in by the missionaries and their Yali helpers.

Four years later the mission renewed their efforts to set up their station. This time the Nipsan people received the mission more favorably, and there are now about 3,000 followers spread over 25 congregations in the area.

A Moni man from the highlands near the Kemandoga Valley.

The Kimyal

The 20,000 Kimyal were one of the last major groups to take their place on the ethnographic map. Robert Mitton, writing in The Lost World of Irian Jaya in the 1970s, called their territory "True cannibal country." In 1968, two Protestant missionaries, Australian Stan Dale and American Phil Masters, were killed and eaten while hiking from Korupun to Ninia (see "Missionaries," page 46). In the same area several years later, anxiously awaiting their helicopter amidst hostile natives, Mitton writes: "we could have been eaten and defecated by the time it got to us." When they were finally rescued, the Kimyal shot farewell arrows at the helicopter.

Linguistically and culturally related to the Kimyal are the Eipomek, or simply Mek, living around Eipomek, east of Nalca. (Older texts refer to this group with the silly, and unflattering moniker "Goliath pygmies.")

The Eipomek are short-statured mountain people, and dress in rattan hoops. Many of the men wear nosepieces of bone and feather headdresses. Unlike many highlanders, the Eipomek play long, thin drums, decorated in motifs much like Asmat drums.

The Ekari: born capitalists

Furthest to the west of West Papua's highlands, in the fertile Paniai Lakes and Kamu Valley region, live the 100,000 Ekari. The Ekari (in some texts, called Kapauku) have been among the most successful of West Papua's ethnic groups in making the transition to modern ways of life. One anthropologist, Leopold Pospisil, has called them "primitive capitalists" for their acquisitiveness and culture based around property ownership.

[Note: as of this writing, the Paniai Lakes region is off limits to tourists.]

Of all highland groups, the Ekari have proved the most responsive to government programs such as improved animal husbandry and agricultural techniques. The first contact with the West came in 1938. One subdivision of the group came under strong Roman Catholic influence after 1948 while others hosted Protestant missionaries.

Many groups in Melanesia are led by non-hereditary chiefs called "Big Men" who achieve their status through personal initiative. In West Papua, such Big Men rise to their position through skills in war, oratory and trade, in varying combinations. The Ekari chiefs are an extreme example of wealth-accumulating Big Men, depending on successful pig breeding, which in turn requires a large, polygamous household. This enables the leader to extend credit by lending pigs and to show his generosity to his followers.

The Ekari have no concept of a gift—everything is leased, rented or loaned with elaborate calculations of credit and interest. Just about everything can be settled with suitable payments, including crimes such as rape, adultery and murder. A fee was even charged for raising a child.

After Dr. Pospisil gave the tribe a lecture on agriculture, he was given several chickens—the Ekari remembered what he had told them earlier about being paid to lecture to students in the United States.

The Ekari, who keep all accounts in their heads, work with a highly developed decimal system, which repeats at 60. Numbers are crucial. When Pospisil showed them a photo of a pretty smiling girl, the Ekari counted teeth. In a photo of a skyscraper, it was the number of windows. Boys considered it a special favor to be allowed to count the white man's "money," a collection of various shells and beads. The anthropologist was kept well advised, ahead of time, when his cash flow was getting behind. Not surprisingly, the Ekari became experts at mathematics when schools opened in their homeland.

Most unusual for a traditional culture, the Ekari have no communal property. Everything is owned, including each section of an irrigation ditch, a part of a road or footpath, even a wood-and-liana suspension bridge.

Conspicuous consumption is taboo: the most valuable shell necklaces are loaned or rented for ceremonies. Persistent stinginess can lead to capital punishment—execution by a kinsman's arrow.

The Paniai Lakes region is fertile when properly cultivated. In addition to the three existing lakes, Paniai, Tage and Tigi, there is another that began to dry out some 15 centuries ago, leaving behind the swampy Kamu Valley. Lake products are harvested exclusively by women, who collect crayfish, dragonfly larvae, tadpoles, waterbugs, frogs, lizards, birds' eggs, vegetables and fruits.

Traditional Ekari religion

The Ekari creator was omnipotent, omniscient, omnipresent and... nonexistent. Only after missionaries arrived did the Ekari name their creator, Ugatame. They believed that since all good and evil came from this being, man had no free will—a most Calvinist philosophy. But religion occupied little of the people's attention. Of the 121 tenets of Ekari belief compiled by Pospisil, only 14 dealt with the supernatural.

Christian missionary efforts ran into problems. The Ekari refused to come to church after one of the missionaries stopped giving out free tobacco upon attendance. "No tobacco, no heleluju," said the men. And because the highlands get awfully cold at night, the Christian hell didn't seem like such a bad place—warm, and nobody had to gather wood. (See "Missionaries," page 46.)

First contacts with the west

In 1936, the Ekari saw an airplane fly overhead for the first time. The pilot, a certain Lieutenant Wissel, was credited with discovering the area and the lakes were named after him. (In 1962, the name was changed to Paniai.) Even many years after the event, the Ekari clearly remembered exactly what they were doing when the plane came.

In 1938, a Dutch government post was established at Enarotali and missionaries soon followed. World War II interrupted the process of modernization. The Japanese soldiers forced the tribesmen to participate in labor gangs and to feed them, leading to resistance and deaths on both sides.

After the war, the Dutch returned and the pace of change picked up. Thanks to the good advice of Roman Catholic priests, the Ekari radically improved the utilization of their lands by building large-scale irrigation ditches to prevent flooding.

The construction in 1958 of an airstrip at the western edge of the Kamu Valley, which brought in cash wages, ended the Ekari youths' dependence on loans from their rich elders, leading to a loss of influence and prestige for the older generation.

The Ekari became long-distance traders. They even began to rent missionary airplanes to take pigs and other trade items to outlying areas. Dr. Pospisil, who wanted a ride on one of these flights, was told he could—for a fee. He was directed to sit in back with the pigs. When he objected because he wanted to take photos, he was allowed to sit next to the pilot—for an added charge.

The ending of warfare and the speedy acceptance of western medicine led to a great population increase, and many Ekari have left to seek a livelihood outside their homeland, especially after a road connected the Kamu Valley with the district capital of Nabire. By 1975, over 2,000 Ekari had settled there.

In Nabire, the traditional Ekari pragmatism and economic philosophy has served them well. Ekari couples are famous for their thrift, hard work, and purposeful accumulation of capital. No other highland tribe has entered Indonesia's modern economy with nearly as much vigor.

A Moni woman and her child.