Читать книгу Indonesian New Guinea Adventure Guide - David Pickell - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMISSIONARIES

Bringing the

Word to a

'Heathen' Land

Missionaries have been active in West Papua for well over a century. When in 1858 Alfred Russel Wallace arrived in Dore Bay (near present-day Manokwari), he met Johann Geissler and C. W. Ottow, two missionaries sent by The Christian Workman, a Dutch Protestant mission. Although these two (and a third who followed) learned the local language and eventually established four stations in the vicinity, during the next 25 years more of their party died in New Guinea than natives were baptized. One account refers to these deaths as "rather prosaic martyrdoms of malaria."

Protestants and Catholics

During the 1890s and the early 1900s, as Dutch administrative control gradually spread through West New Guinea, many more missionaries arrived. The colonial administration, in the Boundary of 1912, created a duplicate of Holland herself, decreeing that Protestants should work the north and Catholics the south.

The results of this division are still visible today, with more Catholic converts found in the south and more Protestants in the north. Since 1955, however, the various faiths have been free to proselytize anywhere, and consequently have made inroads into each other's "territories." Recently, American fundamentalists have made great progress in the highlands.

Protestant Christianity is the religion of over 200,000 West Papuan highlanders as well as most inhabitants of the coastal areas, except for the cities, where many of the recent arrivals are Muslims from other parts of Indonesia. The Mission Fellowship, an umbrella organization which coordinates the activities of nine separate Protestant groups in West Papua, comprised 182 individuals at last count Most Protestant missionaries are married, and the majority are Americans. Many Protestant churches are also now run by Indonesian pastors.

The Catholic missions, staffed by 90 priests, 26 brothers and 95 sisters, are divided into four dioceses. The diocese of Merauke claims more than 100,000 Catholics, Agats 20,000 plus, Sorong 20,000 and the Jayapura diocese some 70,000 converts, with about half of them living in the Paniai Lakes region. The Catholics claim that 220,000 West Papuans—about one-fifth of West Papua's total population—practice their faith.

Converting the highland tribes

In 1938, a year after the Paniai Lakes of western West Papua were discovered, the Dutch opened their first post at Enarotali. This same year, the first Roman Catholic missionary arrived at the westernmost extremity of the highlands. Shortly thereafter, the first American Protestant missionaries arrived, following an 18-day, 100 kilometer hike through torrential rains from the coast.

As the result of a "gentlemen's agreement," the western highlands were divided into two spheres of influence—the Catholics took the area around Lakes Tigi and Tage (as well as in the Moni enclave of Kugapa in the east) and the Protestants the Ekari territory on the shore of Lake Paniai.

One of the immediate results was hyperinflation in the native currency of cowry shells, as the missionaries brought with them huge supplies of shells to finance their operations with native labor. Gone were the days when one cowrie shell would buy a 5-gallon tin of sweet potatoes and 50 of them fetched a wife or a fat pig. It soon took 2 steel axes and 240 blue porcelain beads to convince a porter to carry a pack on the 13-day trek from Enarotali to Ilaga.

A missionary nurse administers antibiotics to a family in East New Guinea. Photograph courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History.

Life was not easy for these early missionaries in West Papua. Hob-nailed boots were essential for hiking across moss-covered logs, slippery trunk bridges and frequent mud. A pair of these tough boots could be worn out in a week. Exhausting treks were necessary to scout out locations for new missions. Months of hard work by natives paid with steel axes were required to carve airstrips out of the steep slopes. Small planes first dropped in supplies and then, when the strips were complete, transported missionary wives and children and a plethora of goodies with which to tempt the West Papuans.

Cargo cults

West Papua's highlanders, for their part, often confused these strange foreigners with powerful ancestral spirits who were believed to help their descendants if proper rituals were performed. Thus when the whites arrived with their enviable material possessions, the natives assumed that rituals performed by missionaries, such as eating at tables, writing letters and worshipping in church, were responsible for the arrival of such goods. One can imagine how it appeared when spoken appeals to a metal box led to a seemingly endless supply of steel axe heads, metal knives and food being dropped from the sky.

This led to the development of "cargo cults"—mystical millenarian movements (the highlanders also believed in a "second coming"—a golden age of immortality and bliss). In Papua New Guinea (where there has been more research), these cults led to the construction of model airplanes and mini-airstrips in hope the spirits would send them planeloads of goods ("kago" in pidgin English).

The cargo cult mentality, which was widespread throughout Melanesia, gave a boost to the missionaries' message in western New Guinea. Many people at first thought of the whites as demi-gods, both for their incredible material possessions and for their "magic" in curing disease. This belief was heightened because the whites murmured mysterious incantations over their patients as they cured them (with a quick shot of penicillin) from the disfiguring skin disease called yaws that plagued the highlands.

Cargo cultism no doubt contributed to the American fundamentalists' success in the highlands, but great energy and sacrifice also contributed to the evangelical drive. Particularly effective were the native preachers, first from a Bible school on Sulawesi and then from among the highlanders themselves.

The mission station at Pyramid, run by American Protestant missionaries, is the largest in the highlands.

Success among the Damal

Following the Allied victory in World War II, the Christian and Missionary Alliance (CAMA) established its headquarters in Enarotali on the Paniai shore. Following up on their pre-World War II work, Protestants trekked east from the Paniai to their former post in the Kemandora Valley. From here, a station was built in Homeyo, among the Moni tribemen controlling the highlands' best brine pools.

By 1954, the missionaries reached the Ilaga Valley, about halfway along the 275-kilometer path between Paniai and the Baliem Valley. The Ilaga region is the hub of a wheel of valleys where fertile soils provide abundant harvests of corn, beans and peas, in addition to the staple sweet potato. The abundance of raspberries here led to the practice of using raspberry juice, along with chunks of sweet potato, for communion. The first converts were 1,200 Damal tribesmen living here as a minority in a Dani area.

While victories were being won for Christ in the Ilaga, back at CAMA headquarters serious difficulties had arisen. A widespread pig epidemic was blamed on the spirits' displeasure with the foreigners. The Ekari at Enarotali revolted, killing their Christian tribesmen as well as an Indonesian preacher and his family. They also destroyed the mission airplane, which was crucial for ferrying supplies to the highland stations. The troublemakers were finally subdued—not by Dutch rifles and mortars, but by well-aimed Christian arrows.

On to the Baliem Valley

In 1955, under pressure from the influential Roman Catholic political party, the Dutch parliament finally passed a bill allowing unrestricted activities on the part of all mission societies in West Papua. After some brief explorations and the establishment of a station at Hetegima at the southern end of the Baliem Valley, Protestants began expanding into the previously off-limits Baliem at a rapid pace.

The mission at Pyramid, at the northwestern end of the valley was the first to be established. A major trade route already led here from the Western Dani centers of Bokondini, Karubaga and Mulia. Because of its strategic location, more missionaries were sent to Pyramid than anywhere else, and the mission retains its importance today.

The western valley station at Tiom, and one at Seinma in the Baliem Gorge area south of Hetegima, were both opened in 1956, one year before the Dutch government established its first outpost in the valley, at Wamena. In 1958, a year after Wamena was established, Catholics entered the valley.

When Dutch control came to the Valley, the various Protestant sects—CAMA, the Australian Baptist Missionary Society, the Regions Beyond Missions Union, and the United Field Missions—joined forces for financial and logistical reasons as well as to counteract the Roman Catholic presence. The Catholics' more flexible policy toward native beliefs was a sore point with more fundamentalist Protestants. Said one polemicist, "the Catholics' attempts at accommodation have at times produced hybrid creeds scarcely recognizable as the continuation of historic, Biblical Christianity."

With the competition for souls heating up, gone were the "gentlemen's agreements" of old. But old-fashioned Protestant missionaries who, for example, insisted on clothing being worn in church, were also fading. Younger, more open-minded Americans who had taken university courses in anthropology and linguistics after their years of Bible college were now joining the ranks. This new breed of missionaries enjoined only against those practices that were in direct conflict with the Bible—killing the second twin born, spirit worship and the execution of women accused of witchcraft.

Fearing a Catholic monopoly on education, the Protestants also agreed to participate in secular educational programs sponsored by the Dutch government. And, albeit reluctantly, the Americans also participated in setting up a government-subsidized public hospital at Pyramid.

'Pockets of heathenism'

In the early 1960s, the pace of missionary activities slowed. The country was undergoing a difficult transition from Dutch to Indonesian rule, and the frenetic pace of evangelical advances had left numbers of unbelievers as well as "pockets of heathenism" in the minds of the recent converts. It was time to consolidate gains.

Preachers found that even well-behaved flocks were sometimes operating with pretty strange notions of Christianity. Some West Papuans believed that sitting in church would result in immunity from sickness, and that forgetting to shut one's eyes during prayers would lead to blindness. Missionaries responded to these setbacks and superstitions by swearing to persevere against this "black magic," which one called "Satan's counteraction to God's perfect will for man."

The Protestants, resolving their internal difficulties, at this time planned a two-pronged strategy to conquer the remaining Western Dani—moving eastward from the Ilaga Valley and northwest from Pyramid. Setting aside jealousies and theological differences, the Australian Baptist Missionary Society joined forces with Regions Beyond Missions Union to help the United Field Missions build an airstrip at Bokondini. Areas thus opened up were divided into exclusive spheres of influence.

From Bokondini, missionaries trekked to Mulia to spread the gospel to the "crazy people"—Danis suffering from huge goiters and giving birth to cretins. Disease in this tragic place, the "most concentrated goiter pocket in the world," was soon cleared up with iodine injections and prayers. By 1963, a conference in Bokondini attracted 51 Dani church leaders. In the same year, Bokondini became the site of a teacher-training school.

While the Gospel swept into Western Dani areas, the Baliem Valley offered surprisingly stubborn resistance. Powerful war chiefs here resisted the new creeds, correctly viewing them as as a direct threat to their authority. A man who has more than 20 confirmed kills to his credit isn't going to give up his hard-won prestige to a religion that proposes that "the meek shall inherit the earth." Many leaders also objected to the secrets of salvation being revealed to women—religious lore had always been a male preserve.

There were other reasons for a slowing of proselytization here, too. With the civil government providing medical care and newly arrived merchants offering essential material goods, Bible preachers lost some of their punch. In fact, the greatest concentration of Dani who today refuse Christianity live in and around the administrative center of Wamena.

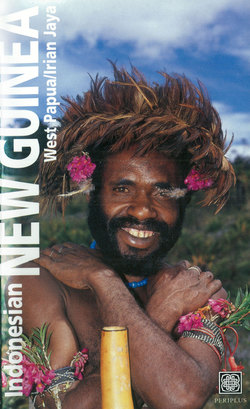

American missionary John Wilson poses with a Dani man at Pyramid.

Life among the cannibals

The life of a missionary in West Papua was not easy. (This is not to celebrate their suffering; missionary efforts in West Papua have inflicted great hardships on the West Papuans.) One story involves Stanley Dale, an abrasive former Australian commando, and Phil Masters, an American, who were dispatched to convert a group of Yali villagers in the area east of Ninia, between the Heluk and Seng Rivers.

For a while, the Yali believed that the two newcomers were reincarnations of two of their deceased leaders, turned white after passing through the land of the dead. But they soon realized the missionaries were ordinary humans, and following several misguided attempts at "reform"—including mass fetish-burning—killed them. In 1968, the bodies of the two men were found riddled with arrow shafts "as thick as reeds in a swamp."

Another tale involves Dutch Reverend Gert van Enk, 31, a tall, tropics-cured veteran of five years' service, who has been working among the Korowai tribe, around the upper Becking River, in what he calls the "hell of the south." The Dutch Reformed Church has been trying to proselytize the 3,000 Korowai for ten years and so far has not celebrated a single baptism. Van Enk is not allowed into most of the tribal territory, and if caught there would be pin-cushioned with arrows. But he has no thoughts of giving up. His countrymen, he says, took centuries to become Christians.

Missionaries and progress

Although the methods and mission of Third World evangelical Christianity are today routinely questioned, missionaries in West Papua have often played a positive role in easing traditional West Papuans into the 20th century. They have brought medicine, and have often served as an important buffer between the government and the people.

The sensitivity of the church to local customs is today greatly improved. Even fundamentalist Protestants now allow worshipers into their churches wearing penis gourds, and local West Papuans are groomed to take over positions of leadership within the church.

John Cutts, the son of missionaries, grew up with the Moni near Enarotali. The mission's ultralight airplane allowed him to land at even the tiniest of bush strips.