Читать книгу Buck Whaley - David Ryan - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

MAKING A BUCK

I was born with strong passions, a lively imagination and a spirit that could brook no restraint. I possessed a restlessness and activity of mind that directed me to the most extravagant pursuits; and the ardour of my disposition never abated till satiety had weakened the power of enjoyment … In the warmth of my imagination I formed schemes of the wildest and most eccentric kind; and in the execution of them no danger could intimidate, no difficulty deter me. (W, 335)

So wrote Thomas ‘Buck’ Whaley towards the end of his short life, evoking the powerful and wayward spirit that set his days ablaze, from the follies of his youth to the hare-brained schemes, remarkable adventures and crushing disasters of his adulthood. It was his sheer heedlessness, his willingness to do the unthinkable in the face of all sense and advice to the contrary, that made Whaley such an attractive character, not only to his contemporaries but also to us today, over 200 years after his demise. The same volatile and adventurous disposition that ignited his spectacular expedition to Jerusalem also set him on the road of calamity and financial disaster, a path he struggled on until his untimely death at the age of 34.

When Whaley was born in 17651 there was little to suggest that he was destined for such a reckless and dissipated life. His father, Richard Chapel Whaley, was a prominent Anglo-Irish landowner who had carefully consolidated and augmented the extensive landed wealth he had inherited from his forebears. Richard’s great grandfather Henry Whalley had been a first cousin of Oliver Cromwell and a firm supporter of the parliamentarians during the English Civil Wars between King and Parliament in the 1640s. In 1649 Henry Whalley’s brother Edward, along with Cromwell and others, signed Charles I’s death warrant. Later that year Cromwell embarked on his conquest of Ireland, crushing and dispossessing the Irish Catholics who had sided with the king during the conflict. Many parliamentarians received grants of the confiscated estates and Henry came into substantial property in the Galway area.2

Over the generations that followed his descendants added to this landed fortune. In 1725 his great grandson Richard Chapel Whaley inherited the Galway lands, and some years later his uncle bequeathed him property in Armagh and Fermanagh.3 Richard was a canny entrepreneur and in 1755 he invested ‘to very great advantage’ in a copper mine near Whaley Abbey, his home in the foothills of the Wicklow Mountains.4 The money amassed from investments like this enabled him to acquire further estates in Dublin, Wicklow, Carlow and Louth. By this time he and his fellow upper-class Protestants had become a powerful elite in Ireland. Their victory in the Williamite War (1688–91) had enabled them to seize yet more property from the Irish Catholics and in the early-eighteenth-century Protestants, though a minority, owned some 80 per cent of the land in Ireland. They also controlled the Irish Parliament and the legislature. Determined to keep Catholics in a subordinate position, they introduced penal laws prohibiting them from practising their religion, owning land, voting or holding public office. The laws were only sporadically enforced but Richard Chapel Whaley was one of their firmest advocates, partly because he used them for his personal gain. When engaged in his mining venture he seems to have defrauded his business partner, a Catholic named Bolger: ‘Whaley took advantage of the penal laws to rob him and prospered on the ill-gotten plunder.’5

Unsurprisingly given that he was the descendant of a Cromwellian, Whaley was also keen to enforce the penal laws for their own sake. The aftermath of the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745 saw the laws ‘revived in Ireland without cause, and pursued by a few weak bigots with avidity; rewards were offered for apprehending priests, and the fellows who pursued this infamous avocation were termed priest catchers’. Whaley was said to be an ardent priest-catcher, leading expeditions into the countryside in search of his prey. At some point he became known as ‘Burn-Chapel’ Whaley: according to one tradition, he got the nickname when he fired his pistol at a Catholic chapel and set its thatched roof alight, burning it to the ground.6 It seems the attack was motivated by Whaley’s animosity towards a Father Byrne, a Catholic priest who lived at Greenan Beg near Whaley Abbey. Byrne’s sister was married to a Protestant named Willis or Wills, and while dining with her one day the priest had given ‘umbrage to a Protestant of the party by stating that Protestants would be lost’. In retaliation for this, and no doubt keen to deal with the Romish cleric in his midst, Whaley recruited a pair of thugs named Collins and Quinsey and set fire to the Catholic chapel at Greenan. The three men are said to have used a picture of the Virgin Mary for target practice, with Whaley exclaiming ‘I shot the wh[or]e through the heart and she did not bleed.’ Whatever the truth of the story, the ‘Burn-Chapel’ moniker stuck and would endure long after his death.7

It was not the only legacy he had to worry about. As the owner of estates scattered over seven counties – Dublin, Wicklow, Carlow, Galway, Armagh, Louth and Fermanagh – he needed to produce an heir who could carry on his name and property, but his first marriage, to Catherine Armitage, had been childless. When Catherine died in November 1758 Whaley, now in his late fifties, decided to remarry. Youth and good looks must have been among the qualities he sought in his new bride because she turned out to be Anne Ward, the 18-year-old daughter of the Rev. Bernard Ward, Rector of Knockbreda in County Down.8 With her lustrous dark hair and prominent nose Anne was arrestingly beautiful. She also possessed ‘captivating manners, a well-cultivated mind and the most incorruptible virtue’. (W, 9) The dramatist John O’Keeffe (1747–1833) described how she and Whaley met:

[She] went to Dublin, on a visit, and with some female friends was one day walking about to see the fine buildings, as she had never been in town before. On viewing Stephen’s Green, they stopped before a house, with a large carved stone dormant lion over the door; as they were admiring this, a person standing near, asked them to walk in and look at the house; they consented, and he led them all over the apartments, which were furnished in the first style, but they saw no one but their polite guide. They were much pleased, and, expressing great admiration, were thanking him, and taking their leave, when, in a particular and pointed manner, he asked the country lady [i.e. Anne Ward] … whether she liked all she saw; with great pleasure she said she did. ‘Then, madam,’ he replied, ‘this house and all it contains is mine, and if you wish to make it yours also, you may have the house and the master of it;’ – making her a low bow. A marriage followed.9

O’Keeffe claimed to have had the story from Anne’s brother and it has the ring of truth, apart from one detail: Whaley had not yet started building the house with the lion over the door. When he met Anne he was living in ‘prince-like magnificence’ at No. 75 (now No. 85) St Stephen’s Green and this must have been the dwelling he showed her around. Designed by the German architect Richard Castle, this stone-fronted townhouse is now part of Newman House, an administrative centre of University College Dublin. It has been carefully restored and boasts a lavishly decorated interior. Its front parlour, the Apollo Room, has magnificent stucco ornamentation, while the Great Room or Saloon is regarded as one of Ireland’s finest eighteenth-century interiors.10 Whaley must have seemed a decidedly eligible widower and Anne was sufficiently impressed to overcome whatever reservations she had about marrying a man forty years her senior. For his part he was besotted with his bride-to-be, who he described as ‘my soul’s darling’. The marriage took place in February 1759, just three months after Catherine’s death, and Anne settled into the role of dutiful wife. Her son would later praise the ‘undeviating rectitude of her conduct towards my father, notwithstanding the disparity of their age, which would have been sufficient to have excited the malevolence of slander against her, had she given the least opening for it, by any levity in her behaviour’. (W, 9)

The marriage was certainly successful if judged by the number of offspring it produced. The year 1760 saw the birth of a daughter, Mary Susanna, followed two years later by a son, named Richard Chapel after his father. Whaley was reported to be so delighted at the birth of his son and heir that he made his wife a present of £10,000, sending his banker a note in the form of a piece of doggerel:

Good Mr. Latouche,

Prithee open your pouch,

and pay my soul’s darling

Ten thousand pounds sterling …11

With the arrival of a further two daughters, Anne and Frances Sophia in 1763 and 1764 respectively, Whaley decided that his present residence was too small to meet the needs of his growing family.12 He set about building a new house on an adjoining plot of land. It was to be a huge mansion with five bays and four storeys over a rusticated basement and when completed it would dwarf No. 75 (see Plate 1).13 Over the portico Whaley installed a lead statue of a lion by John Van Nost II (c.1710–1780), then Ireland’s leading sculptor. Seemingly just awoken from its slumber, it gazes sombrely across at St Stephen’s Green.14 The mansion was similar in design to another great Dublin townhouse, Charlemont House, although its exterior was not as elegant. The interior was a different matter. Whaley hired skilled artists to produce some of the finest stuccowork in eighteenth-century Dublin. The stucco decoration on the walls and ceiling of the main staircase is breathtaking (see Plate 3). Many of the rooms also feature fine stuccoed ceilings, and in the ground floor drawing room there are two small portrait heads above the central wall panels, possibly representations of Richard Chapel Whaley himself.15

When not busy overseeing the construction and decoration of his palace Whaley concerned himself with the management of his estates, for which he relied heavily on his ‘honest’ and ‘faithfull’ servant and land agent, Samuel Faulkner. At this time Faulkner and his wife Catherine were living with the Whaleys, but they would later move into a place of their own a few doors down at No. 84 (now No. 96).16 Born around 1721 near Cookstown, County Tyrone, Faulkner was a no-nonsense Ulsterman known for his blunt language. On one occasion, suffering from diarrhoea, he claimed to have been ‘not less than 13 times at stool … at night[.] this would kill an elephant’.17 Hard-working and meticulous, he also acted as agent for several other landowners and kept copies of all his correspondence.18 Though his life was marred by tragedy – his wife and one of his nephews predeceased him – he was kindly, generous and well-liked. But Faulkner must also have had a ruthless edge to him; otherwise he would not have been able to perform the work of a land agent: letting property, collecting rents and arrears and, occasionally, carrying out evictions. In March 1765 Whaley gave Faulkner power of attorney to ‘receive all moneys rents and arrears of rents’ that were due to him while also instructing him to recover some property belonging to him ‘by any means without blood shed or burning a house … do the thing with spiritt and I will support it’. The fact that Whaley referred to ‘blood shed’ and ‘burning’ at all suggests that he and Faulkner may have used these methods in the past.19 They had known one another a long time and their relationship was one of friends rather than employer and employee.20 For the Whaley children, who knew Faulkner from birth, he seemed more like an affectionate uncle than their father’s agent.

***

On 15 December 1765, several months after work had begun on the new house, Anne gave birth to her fifth child. Thomas Chapel Whaley was baptised exactly two months later at St Peter’s Church on Aungier Street.21 Known to his family as Tom, this fair-haired blue-eyed boy captured his mother’s heart, more so perhaps than any of his siblings, but she had little notion of the extraordinary life that lay ahead of him or the worry he would cause her. Nor was he the last child she would bear. Over the next couple of years a further two boys, John and William, arrived. Perhaps sensing that his family was now complete, Richard Chapel Whaley commissioned a sculptor, Patrick Cunningham, to commemorate them in an unusual portrait: a wax bas-relief intended for display on a chimneypiece in the new house (see Plate 2).22 Here the ageing father appears as a kindly patriarch surrounded by his loving wife and children. He gazes devotedly at Anne as she tends to the seventh and youngest child, William, seated on her knee. To the left the eldest daughter, Susanna, sits seemingly preoccupied at a small desk, while to the right the eldest son, Richard, tugs at his father’s sleeve, eager to show him something or involve him in a game. Beside him the second daughter Anne is dancing, anticipating her later career as a socialite. At the extreme right the third daughter, Sophia, plays with some fruit. Beside her the toddlers, 2-year-old Tom and 1-year-old John, play on the floor. Both are attired as girls: whether male or female, infants were dressed in floor-length gowns worn over stiffened bodices or stays. It was not until between the ages of 4 and 7 that boys were ‘breeched’, i.e. given male clothing. Tom holds a rattle in his hands, an inauspicious symbol of the ‘play’ he would devote himself to in later years: gambling.

Richard Chapel Whaley took great joy in the beautiful wife and children that came to him so late in life, but he did not enjoy their company for more than a few years. By the end of 1768 he had fallen ill and the following February he died.23 After he had been buried in the Whaley family vault in Syddan, County Meath, his widow returned to St Stephen’s Green. Not long afterwards the new house was completed under Faulkner’s direction and the family moved into it. Now aged around 28, Anne faced bringing up her seven children without the support of a husband. Yet she was better placed than most widows to do so. She could rely on the help of the Faulkners (Catherine Faulkner acted as her maid) and her father, the Rev. Bernard Ward, who was guardian of the fortunes of the Whaley children. She also had the money to employ as many servants as she needed.24 Many years later, Tom commended her for bringing her children up ‘in the paths of religion and virtue … whatever follies any of us may have committed, the cause could never be imputed to her’. (W, 9)

Populated by a large family and a considerable staff of servants, the newly built mansion on St Stephen’s Green must have been a lively place. The children would have played in the stately rooms and corridors, causing mischief and getting in the servants’ way, while their mother or one of the Faulkners watched over and perhaps chided them. Over a century later, in his autobiographical A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, James Joyce hinted at feeling Tom Whaley’s presence in these hallways: ‘The corridor was dark and silent but not unwatchful … was it because he had heard that in Buck Whaley’s time there was a secret staircase there?’25 In the dining room, a large chamber with a richly stuccoed ceiling at the rear of the house, the family were served by a posse of attendants. French cuisine was in vogue and Anne and the older children may have tucked into a variety of exotic dishes such as lambs’ ears ragoût, fricassée of frogs and badger flambé.26 If so this influenced Tom’s culinary tastes as he employed a number of French cooks later in life. At the close of day the family retired to sleep in their rooms at the top of the house. One of the bedrooms looked out onto the back yard and stables and beyond that a green area known as Lord Clonmell’s Lawn (now the Iveagh Gardens). This may have been where Tom slept as a child. Over a hundred years later it was the bedchamber of the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins.27

It was unlikely that Anne would stay a widow. She was still young, attractive and fashionable and, as befitting a lady of her station, turned herself out in fine gowns and dresses, among them a Latin gown which she wore with a blond stomacher and ‘sleeve knots with French flowers’.28 More than a few gentlemen must have had their heads turned by this beautiful and wealthy widow and it was only a matter of time before she settled on a new husband. He turned out to be John Richardson, the son of a County Derry rector and a member of the Royal Dublin Society. A kind-hearted and affable man who would later enter politics as MP for Newtown Limavady, Richardson was the same age as Anne and seemed disposed to be a good stepfather to her children. They married at the end of 1770. It was a joyful union. ‘You have no notion how happy I am,’ Anne wrote to Faulkner a few years later, ‘and it is not at all extraordinary that it shou[l]d be so, I am blest with the very best husband upon earth’.29

Yet she also suffered tragedy. On 12 August 1772 her eldest son, Richard Chapel Whaley Junior, died. He was 10 years old. We do not know what occasioned his passing but it must have caused his mother and siblings great sorrow. Yet for the next oldest brother, Tom, the event had special significance. Under the terms of his father’s will, he had only stood to inherit leasehold lands in County Armagh. But now that he was the eldest surviving son he was also entitled to the extensive Carlow estates and the Dublin properties including, if he outlived Anne, the house on Stephen’s Green.30 The annual rental income from the Whaley estates came to £6,876 and Tom also stood to inherit the lion’s share of his father’s personal fortune of £43,630, which earned over £2,500 per annum in interest.31 His mother and grandfather did not tell him the amount of his inheritance but he knew it was very large and henceforth he would wait impatiently for the day when this wealth would pass into his hands. This certainly spurred some of the extravagance and recklessness he manifested during his teens. We will never know if he would have led a more prudent life had his brother survived – what we know of his temperament suggests he would not have – but if nothing else he would have had less wealth to squander.

Around the middle of 1773 Anne went to live with Richardson in Ulster. She seems to have brought her daughters with her, leaving her three surviving sons in the Faulkners’ care. Even though Richard junior’s death the previous year must still have been on her mind, this was a blissful time for Anne and her new husband. For most of the ten years that she had been married to Richard Chapel Whaley her days had been consumed with bearing and raising children. Now, happily married to Richardson, she was enjoying new-found freedom and ‘better health … than I have done for several years’. One suspects that she was also enjoying a break from rearing her boys. Tom, John and William were now aged 7, 6 and 5 respectively and must have been a handful. At the same time she missed them and at the end of the year she wrote to Sam Faulkner asking him to bring them to spend a month with her the following April or May.32 During the summer months she and Richardson again took up residence at the house on St Stephen’s Green, which was reportedly ‘frequented by the first people in the kingdom … the proprietors are not only very rich, but have great interest [i.e. influence]’.33 When Anne and her husband were absent, Faulkner had to keep the Whaley boys amused. Tom had a particular interest in exotic animals and Faulkner found himself bringing him to see the ‘wild beasts’: probably a private menagerie, as there were no zoological gardens in Dublin at the time.34 Luckily, he did not have to keep him entertained indefinitely. The time had come for him to be sent away to school.

Portarlington in the Queen’s County had been renowned for its boarding schools since the early eighteenth century. Most of them were run by Huguenots who had come to Ireland fleeing persecution in France. A large community of these immigrants had settled in the small town in the Irish midlands, where they filled a gap in the market for the education of upper-class Protestant children. By the middle of the century the number of schools in Portarlington ran well into double figures, with nobility and gentry from all over the country sending their children there to be educated. Tom probably attended Robert Hood’s school, a boarding school where students learned writing, grammar, arithmetic, English, French, classics and dancing; or the Rev. Richard Baggs’s public Latin school, ‘from which many gentlemen of rank and fortune have entered the College [i.e. Trinity College Dublin] with particular credit’. Baggs’s school taught writing, arithmetic, mathematics, geography, drawing, music and dancing.35

The writing master trained his pupils well, as is evident from the large neat calligraphy of a letter Tom wrote to Faulkner from Portarlington on 21 October 1775. By then his brothers had joined him at school, but he missed his mother and asked Faulkner ‘please to let me know’ when he expected her to arrive in Dublin as ‘she told me in her last letter, that she would send for us then’.36 But Tom was no shrinking violet, homesick and longing to be reunited with his loving mother. His thoughts wandered far beyond the bounds of home or school. Richard Baggs’s school taught ‘geography both antient and modern, as also the use of the globes’37 and if he did go there, Tom would have paid attention during geography class as he had started drawing maps of exotic foreign regions. Earlier that year he had completed a map of southern Africa which he presented to his grandfather on 25 June (‘dedicated to Mr. Ward by his dutiful gd. son Thomas Whaley’). Neatly and fairly accurately drawn, it is an impressive piece of cartography for a child of his age and was probably copied from a map by the London cartographer Herman Moll, which it closely resembles.38 Tom planned to have ‘a good many maps’ ready to show to his mother and prepared several others, including ‘a very large map of Spain and Portugal and the Mediterranean Sea’.39 It was a formative time for the young boy. As he approached his tenth birthday he felt the stirring of an adventurous spirit and a burning curiosity about the wider world. Doubtless he hoped to visit at least some of the places he mapped, and while he would never make it as far as Africa, his early understanding of the geography of the Mediterranean would serve him well later in life.

Tom may still have been at his cartographic efforts over two years later: early in 1778 he wrote to Faulkner asking him to send him ‘a couple of small pencil[s] and two or three brushes’. By this stage he and his brothers had moved to a new school, possibly in Armagh. Tom also asked after Faulkner’s nephew Sam, who had been unwell.40 It did not bode well. The Faulkner boy’s health seems to have been poor and in September 1782 he died. The list of expenses for his funeral makes for poignant reading: a shroud sheet and cap, an oak coffin covered with black cloth, a hearse and horses to bring the body to St Peter’s Church in Dublin, followed by a mourning coach. Tom later wrote to Faulkner to commiserate: ‘one could not say but he [had] as good a life as I [I’ll] drop this subject … excuse me for calling to your mind a thing that must have distressed you very much but as he is happy I hope a manly firmness has reconsiled you’.41 Having witnessed his own brother’s passing ten years before Tom was well acquainted with the inescapable reality of death. Now, as he entered his late teens, he himself was starting to make his first moves towards manhood. His schooldays were over, and he was about to get his first taste of the wider world he had imagined so often while carefully marking out his maps.

***

‘When I had attained my sixteenth year, my mother thought proper to send me to France in order to finish my education.’ (W, 10–11) With this nonchalant statement Tom recalled the most formative and turbulent period of his early life: his grand tour. Travel on the continent was reckoned an indispensable part of the education of the sons of wealthy gentlemen. It was intended to broaden their minds, enhance their social accomplishments and enable them to acquire a range of useful contacts. But they did not always behave like the gentlemen they aspired to be.42 Critics of the grand tour argued that the young men who went on it were too immature to appreciate its benefits and had too many opportunities for drinking, gambling and self-indulgence. Yet most felt that the benefits outweighed the dangers and hoped that under the guidance of their travelling tutors, known as ‘bearleaders’, grand tourists could avoid these pitfalls. As Tom Whaley’s seventeenth birthday approached, his mother, assisted by his grandfather Bernard Ward, made arrangements to dispatch him to France.

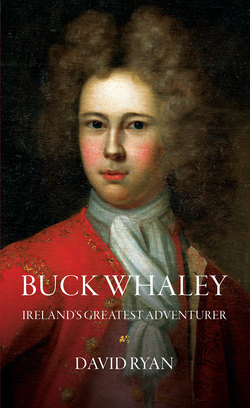

It was around this time that Whaley sat for what was probably his first portrait. The only proper likeness of him that survives today, it shows a boy on the cusp of manhood (see Plate 4). Finely attired in a red coat and pink waistcoat, he stands with one hand on his hip, staring resolutely from the canvas. His face is well-nourished, slightly pudgy even, with the expression of a confident young gentleman readily embracing his life of wealth and privilege. But there is also a certain wildness in his blue-eyed gaze, as if he were liable to do something unwarranted and unpredictable at any time. Like the excitable adolescent he was, Whaley was enthusiastic about the new prospects and experiences that foreign travel would offer him. His grandfather proposed to send him off with a yearly allowance of £500, later increased to £600. This sum would have been sufficient to maintain a prudent tourist, but not a young man eager to be let loose on the world.

His mother trusted that his bearleader would provide wise and strict supervision. For this role she settled on an army veteran named William Wray, ‘who had been recommended to her by some persons of distinction in Ireland’. (W, 11) The son of a County Donegal landowner, Wray had served as a lieutenant captain in the Thirty-ninth Foot, an Irish regiment that spent long periods stationed abroad. This old soldier with a penchant for books and smelling salts had spent much of his life on the continent and seemed a suitable individual to oversee Whaley’s tour.43 But had Anne looked more closely into his past she might have had second thoughts. Wray was a good-natured man but he was not good at managing money. In the army he had found his officer’s salary insufficient to support his lifestyle and had had to sell his commission to pay off his debts. As well, he was in bad health – the result of youthful overindulgence – and he lacked the ‘firmness of character necessary to superintend the conduct of a young man’. (W, 11) Wray hardly seemed a model of prudence and discretion. As a contemporary writer put it, he ‘was supposed to be a fit person to undertake the direction of young Whaley’s studies. It soon however appeared that the tutor had not the ability.’44

It was arranged that Bernard Ward would accompany Whaley to Bath, where they would rendezvous with Wray. The young grand tourist and his bearleader would then leave for Paris, where the grand tour would commence. But neither Anne nor Ward nor Wray could have anticipated the series of disasters that would unfold in the course of Whaley’s travels. He set out brimming with energy and optimism, but he would return a year and a half later distressed and disarrayed, having abandoned his tutor and endured a remarkable series of misfortunes that left him physically shattered and thousands of pounds in debt.