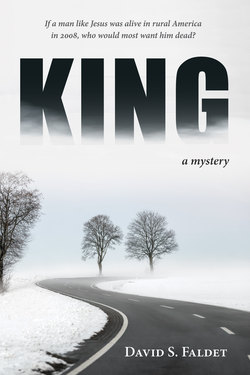

Читать книгу King - David S. Faldet - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Prologue

ОглавлениеMost of my life I have believed in what I can see, what I can smell, what I can rub between my thumb and forefinger. I’m writing to set down a record of my brother, Joshua King: what I saw and heard, the effect I saw him have on others.

Sadly, my brother is dead. Some question the story of his life. Others question the reality of his death. I want to give you the facts about Josh—let you decide what’s true.

I’ve got problems with this. First, I’m an archeologist. I have experience writing e-mails. I can write about a potsherd discovered in stratified or disrupted soil, but have no practice putting into words the feelings of the maker of the pot. I can record transactions, facts, reports about inert material, academic theories, but for Joshua I want to use words that give a sense of his life and the lives he touched. In such writing, I’m a novice.

There’s also this; my brother was a spiritual person. Josh cared for the life an outside observer cannot see or touch: the life that, as he once told a friend, exists “between the soul and the spirit.” As I’ve already said, what experience do I, trained to work with dried-out bones, broken pots, and charred wood have attending to the world of intention, of feeling, of soul: the life to which my brother pointed as prophet?

My brother is dead. I can’t call him back, can’t ask him describe his thinking as he returned from his wanderings in Mexico and the western states to the familiar territory of Bremer County, Iowa, or have him put into words what it felt like to have a power pass through his hand as he eased a suffering man’s pain. How can I hope to extend, slightly, even a tiny sliver of light into my brother Josh’s inner and now-extinguished existence? What Josh cared about he explained with an analogy. The purpose of a tent, he said, is not the canvas, not the thin outer fabric you easily see and feel, but the kind of space the tent fabric creates inside. So too with the Spirit. My brother, Josh, attuned as he was to the Spirit, was remarkably aware of the true, large inner shape of human lives. He recognized that we are not what we seem to one another. Josh lived with the conviction that our invisible inner life has a purpose he respected, a purpose he lived to see.

How do I come to terms with my brother’s commitment to that invisible life? I do it by reminding myself that the world in which we breathe and scuff our knees, the measurable spectrum of energy, that until less than a year ago, was my chief focus, is maybe 5 percent of the whole universe. The other 95 percent is hidden: dark energy and dark material that only clues us to its presence by the measurable bend it puts on the arc of travel of what we can see and detect. As with the universe of energy and matter, so with Josh. I watched my brother swim and run and butter his bread. I heard him mumble in his sleep. I listened when he spoke. But I could not climb into his skin. When Josh sensed the presence of the Spirit, I could not feel her tug on his pulse or the illuminations she cast into his brain. I could only observe her trace effects, the ones I plan to report. Even though I feel I scarcely knew my brother, I would like you to know him better, to know his message, to know how the light he carried lives on, even after his passing.

To do that, I’ll use my field skills. I have asked questions about the thought and feeling of the security guard who found my brother as he died. I have talked to the woman who eased that security guard’s back of its pain, and who, you will come to find, knew my brother well. I’ve also got my own memories of Josh. By triangulating between those three known bearings, security guard, friend, and the Josh I knew, I hope to give you some sense of Josh’s life and what took it.

But I’ve got to publish those experiences through the medium of language, choosing which words to write, which to leave out. Better to ask me to give birth to a child or to dance the lead in the Russian National Ballet.

Be patient. Be kind.