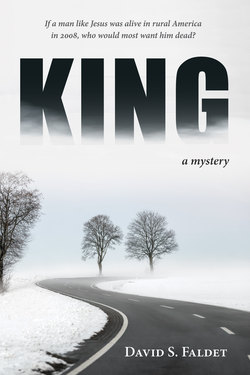

Читать книгу King - David S. Faldet - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

chapter 2

ОглавлениеAfter he was wrapped in a blanket and given hot tea, after he talked to the matter-of-fact deputies, after a tow truck arrived to lift the car, after the hydraulic spreader pried the crumpled windshield frame apart, and after two men eased the body out and retrieved the bloody billfold from the back pocket of the khaki slacks, Mikesh found out the victim was named Joshua King. Then, his shoulders draped in an ambulance blanket, Mikesh finished the careful drive home. He tried to sleep, but it was no good. He had a couple of lagers, staring at a blank window. Over the hoppy fumes of the emptied second glass he finally nodded off. Sitting in his chair, light coming through the morning fog, he woke from a bad dream (a face, blood, everything disappearing in a breath of fire) and found he had a headache. He cleaned himself and changed, took some aspirin, and drove to Decorah to give the full story to a deputy.

Ten years earlier, a dying great uncle left Arnold Mikesh 120 acres of pasture, work land, and woods; a farmstead; a modest chunk of operating capital; and a middle-aged Chevy farm truck. Mikesh took it all, leaving behind a failed marriage and ten years of joyless foot service in the pork futures trading industry. He found a night security job at the community college in Calmar, the hometown his parents had abandoned for the unbroken sunshine of Fort Myers, Florida. Moving to his uncle’s run-down little place near Waucoma, Mikesh used the inheritance to buy the beginnings of a small herd of Murray Grey cattle from which he could raise bloodstock. From where he lived, Waucoma was two miles west, St. Lucas four miles east, Calmar twelve miles northeast. Decorah was an additional ten miles further in that direction. Mikesh occasionally hooked a stock trailer to the Chevy and hauled his Murray Greys to buyers interested in a heifer, a bull, or a pair of finishing steers around Iowa and adjoining states. But Decorah—at eight thousand the biggest town in a five-county area and the seat of the county north of the one he now called home—had in recent years become the typical furthest limit of his day-in-day-out travel. At forty, Mikesh’s world had shrunk to a circle with boundaries rarely more than a fourteen-mile radius of the tiny town where he had attended high school.

Mikesh’s visit to the Decorah law enforcement center began badly. He was directed to an inner reception area near the sheriff’s office. The sheriff’s assistant was on the phone. Mikesh was sure she waved her hand at him, as if to gesture him through the door with Sheriff on it. As he got close he heard an agitated voice. He paused and looked back to the woman at the desk. She gave her head a firm nod as if he should go ahead. As he opened the door the voice said, “Listen, I don’t know anything about it! What he did, he did on his own!” A dark-bearded man, veins bulging on his neck, turned to Mikesh. The sheriff, on the other side of the desk, looked up, startled by Mikesh’s entrance. Mikesh stumbled out an introduction. The sheriff, rising from his chair, eyed him as if he was a housebreaker.

“Who sent you in here?”

Mikesh felt a hand on his shoulder. The woman who had been at the desk was behind him, pulling him back and shutting the door. “Why did you go barging in there?” she said when she had him back in the reception area. Her coffee-brown eyes bored through him. When Mikesh explained that she had gestured for him to walk in, she squinted with mistrust. She led him to a table in a separate room where Jimmy Seegmiller, the deputy on Saturday morning office duty, would take his statement. Mikesh handed her, folded, the blanket sent home with him by the ambulance crew. After that he saw her hover at a desk across the hall, shuffling papers and glancing up occasionally to make sure Mikesh didn’t attempt another breaking and entering. Mikesh’s Bohemian-American grandmother Clarene used to assure him, “The morning is wiser than the evening,” but Mikesh felt like the scant hours of sleep he’d gotten had done nothing to clear his brain of the confusion of last night’s fog.

Jimmy Seegmiller, who arrived at the table knowing nothing of Mikesh’s blundering into the sheriff’s office, sat forward in his seat, savoring the morning’s excitement.

“One hell of a foggy night!” Seegmiller was more interested in relaying office news than in getting Mikesh’s story. There had been a car/deer accident on the edge of town, where a second car plowed into the first. The police took their cruisers off the streets for fear of another rear-end collision. “I don’t need to tell you how long it took the boys to get out to you in that stuff,” Seegmiller went on. “I hear you were in bad shape by the time they got there, Arnie.”

It gave a deputy like Seegmiller a buzz to remind a security man like Mikesh that he had been in something over his head, preferably way over.

“No, Jimmy. You don’t need to tell me how long those folks took to get to me last night. I had on my watch. It was cold. And for half the time I was keeping company with a dead man.”

“Okay, don’t get yourself worked up.” Seegmiller sucked in his belly and straightened in his chair: “we got to go through this.” Seegmiller was in his thirties but had never lost his baby fat: never had, Mikesh guessed, a decent haircut. Before getting his girlfriend pregnant and marrying her, and before signing on with the county, Seegmiller had at least one underage possession charge from the bust at a high school beer party, and a DUI while he was doing assembly line work in Howard county. But now Seegmiller was law. He’d put his bad-boy days behind him, and sheriff’s business kept excitement in Seegmiller’s married life. Since he had never gone out of his way to give Mikesh any trouble, Mikesh wasn’t about to stay sore with him.

“What were you doing, anyway, Arnie?”

“I finished my Prairieview shift at one thirty. It was Friday night, and I was tired. I live on Scenic Road over towards Waucoma. County W44 is the most direct route. The fog was so thick, it was tough work just finding my truck in the parking lot, much less seeing the road ahead of me. What was that guy, the driver, doing out there?”

Seegmiller shook his head with knowing self-importance. “Just so happens they knew at state patrol headquarters where King’s people were: down in Des Moines. King’s been down there these last two weeks for some big come-to-Jesus sort of meeting. Had a run-in with authorities for causing some sort of ruckus, but got released on bail. That gave him a little press the last two days in the capital. Dying on the lam like this ought to keep him in the news another day or two.” Seegmiller paused. “It was a church car he was driving. They had another event scheduled for tonight. Sounds like those people also would like to know what he was doing up here.

“His mother and brother and someone from the church are here.” Jimmy jerked a thumb toward the sheriff’s office. “They’ve identified the body. I got done with them about a half hour before you came. They’re talking to the coroner right now, pretty messed up about this. They want to talk to you, Arnie. They asked for your name.”

Seegmiller leaned towards Mikesh and tapped the top of his ballpoint against the desk for emphasis. “This little event is going to put that rat’s-ass church of theirs out of business.”

“So King led a church?” Mikesh realized that this explained why he didn’t know as much about Joshua King as the people around him. Mikesh and religion, like pickles and cake, were a bad mix.

“That’s just it,” Seegmiller frowned. “It ain’t really a church. It’s more like a cult. And what’s a cult got without the head guy? A bunch of hippie-crazy-free-love-anti-government nuts living out of their VW microbuses, and not a clue in the world about how to keep a job.”

Okay. You, my reading sister, my listening brother, I’m going to stop here, to say that what you just read, just heard, is how Jimmy Seegmiller described Josh’s lifework to Arnie Mikesh. It’s what Seegmiller thought of the group of people I have grown to consider family. Don’t hold it against him personally. Seegmiller, like every other law officer from Des Moines to New Albin, was not disposed to think hospitably about Josh.

I’m pausing the story to say that, recording the unconventional way Josh navigated life, I could use the words I place on the page before you like a privacy fence, concealing what isn’t nice. Instead, I am working to make these words, this story, if I can, a window, an open one. I’m going to let you hear the trash talk you would get in reply, yourself, if you chatted with the law in the county where my brother died. So you know that Jimmy Seegmiller considered me, your source for this story, a hippie-crazy-free-love-anti-government nut. And you won’t be surprised to find that Seegmiller smiled as he pictured the grim future he imagined for my brother’s work, my work. I have lived my adult professional life as an archeologist. In that work a projectile point or a fragment of pottery or a piece of charred wood lying in a clean drawer, disconnected from the place of its discovery, can tell me little. But embedded in dirt and grit that I have carefully measured and chronicled and mapped, these objects can begin to speak. I keep Josh in situ. I leave the grit of Josh’s environment intact. I leave the window open.

“The cult sucks a few straight, decent folks in now and then, gets their money or their business, and that keeps the whole thing afloat. If they are just a church, without their main man, that will all dry up, won’t it?”

Jimmy phrased his last question like it wasn’t a question. Cops love to talk smack, and Mikesh didn’t feel like going down that road. He could still feel the cold, and in his mind still see my brother’s eye looking back at him.

“Like I said, I don’t know anything about that,” he replied.

“In your line of work, Arnie, you don’t have to deal with the kind of crap we get from people like that.” Seegmiller hadn’t put the brakes on yet. “A bunch of gypsies is what they are. And if you have to ask them for an event permit, insurance papers, a vehicle registration, or proof of legal residence, you might as well be talking Bohemian. All you get back is an empty look, a holier-than-thou speech. But they don’t fool me. You don’t talk that line of crap without needing to hide something. And, if you ask me, that probably was true for the boss as well.” Seegmiller focused his anger on my brother. “He was south of the border one too many times for me to believe he didn’t have some kind of junk racket going on to keep the whole thing afloat—marijuana, meth, whatever you’ve got to link up with Mexico to score. The guys from state are checking out his vehicle for drugs, I can tell you that. Maybe as far as that part of the business goes, that church of his won’t need him alive to keep the money coming. But if they find drugs, the state might just be able to put an end to their little business.”

“Listen Jimmy. You are talking about someone I watched die last night. Take it easy, okay?”

“Right.” Having made his speech, Seegmiller needed more oxygen and could start breathing again. “That’s what you’re here for, isn’t it? We need a few more details and a signature. The sheriff wants to speak with you and then you can go.”

The sheriff, in his big office, was neither as talkative nor as excited as Seegmiller. Mikesh could see that Paul Fox bore a grudge against him for his earlier entrance. Fox had moved into the county less than five years earlier and spent only two or three years as a deputy before getting elected sheriff. Even though he ran as a Republican, this was no small accomplishment for an outsider in the tight, conservative world of Winneshiek County. Mikesh pegged him for a man who might have his sights on a bigger pond. Fox had the solid, unexceptional look of a guy who might be modeling casual slacks in the men’s section of a farm-and-home store catalog, but also wore the confident authority of a man with county voters’ mandate to sniff out the criminals that made at least a quarter of them lock their doors at night. Fox sat back in his chair with a wide expanse of desktop between the two of them and studied Mikesh. The accident, Fox said, happened on a county road. It was his jurisdiction to assist in the inquiry, although the state police would take the lead, since it was a fatality. To Mikesh’s surprise, Fox announced that he would be taping the interview. Introductory details completed, with a slightly friendlier tone, Fox asked if Mikesh knew the deceased, and reviewed details of what Mikesh reported last night to the deputies. Slowly Mikesh noticed that the questions were getting less friendly. What had Mikesh been doing between nine and ten p.m. the night before? Was there anyone else at the scene who caught his attention? How in all that fog had he happened to notice that a car was in the ditch? Mikesh came to the office thinking of himself as the helpful neighbor. Fox’s questions put him on the defensive.

Fox sat straight-backed and wrote down Mikesh’s answers. “That car went off the side opposite you on a curve. From every report I got from people out on the road last night, you were lucky to be able to see your own lane,” Fox said. “I just want to make sure you didn’t meet him on that road, weren’t in a place because of all that fog that might have caused him to run off the road like that.”

“I was at work from five o’clock on.”

“Anybody there to back you up on that?”

“I checked in at the beginning of my shift. After that, though, I was on my own. It was a quiet Friday night. No evening classes. Everyone who could be off the road was home.” Mikesh scoured his memory. “I talked to the cleanup guy on the last round of milking at the dairy center, but that would have been before that time, eight thirty, nine at the latest. After that I can’t say that I saw or talked to anyone. It’s possible one of the kids at the apartments saw me on my rounds there. The last would have been around midnight.”

“No one you had to stop, no one you helped, no one else saw you at the school?”

Fox was checking that Mikesh had an alibi that would prove he had not run my brother off the road.

“Listen, I punched in at five o’clock and left work around one thirty. I talked to a guy in the dairy building about nine. On the way home I was watching the road closely and I saw some suspicious tracks in the snow bank. I stopped and found an accident and a victim that no other driver and no sheriff’s deputy discovered in what must have been several hours. If you don’t feel like thanking me for helping your office do its job, that’s fine. But don’t try to come up with a story that makes no sense—not to anyone who knows me.”

Mikesh was tired and angry.

“I just talked to the family and friends of a dead man,” the sheriff told him. “They’re distraught. They want some kind of answer about a fatal accident. I’m going to make sure we don’t overlook anything.”

Fox, in his regulation button-down shirt and his sport coat, talked a good line.

“You can understand why I want to make sure you had nothing to do with this, Arnie. You are telling me you did not pass the scene of the accident any time before you made that 9–1–1 call last night at 1:51?”

Mikesh quit talking. He shook his head.

“Do you have a clearer way of telling me and the recorder that, yes, you were nowhere near the scene before that time?”

Mikesh felt weary. “That’s right. I was nowhere near that scene between the time I clocked in and the time I drove that way home after my shift.”

“Even though you happened by a long time after the crash, you spoke with King. Remind me again if he told you anything about his accident.”

“Not really.” Mikesh wished he could find something of help, something that would put him a bit more on Fox’s side of that awful desk.

“That car flew a ways before it hit the ground. He was going a good speed when he left the road.”

“The tire marks did not indicate the deceased even tried to stop or slow down. And no evidence he had been drinking,” Fox said. “Drugs may be another question. We’ll let the State Patrol investigation and the coroner answer that. It’s a fatal accident. State Patrol is going to go over that car thoroughly. But did you see any sign of drugs? Did you remove anything from the scene?”

“The only thing I touched was the man himself, seeing if I could get a pulse, clear his wind passage, give him a lick of coffee when he asked for something to drink. Beyond that, there was not much I could do. He was wedged in pretty tight. It took a while, even with the hydraulic machinery, for your boys and the EMTs to get his body out. I could see I shouldn’t try to move him. I didn’t take anything. I just pushed my jacket in around him and waited for the ambulance. Within maybe twenty minutes of the time I got there, he was dead.”

“And that left, what? Maybe another twenty or thirty minutes before the emergency response arrived? What were you doing all that time?”

Mikesh tried not to pause, not to sound evasive, but he didn’t like his own answer. “I kept my hand against him. . . . . I was talking to him, not sure when it was he really died. I had my hand on his neck, checking for a pulse so I just kept it there. After pushing my jacket in there around him, it seemed like the one other thing I could do.”

Fox searched Mikesh’s face.

“The jacket you say you pushed around the victim, that is with his effects. We will have to keep it until the investigation is completed. There’s a lot of blood on it.”

Mikesh was quiet.

“So there’s nothing more you can tell me about why you were there, what you saw at the scene, or what you said?”

Mikesh said nothing.

“I see you are a man with a record, and I want to make sure the report for this incident is complete.”

Mikesh felt his blood pressure surge. “That record is for a high school prank.”

“Car theft is more than a prank.”

Fox had unearthed the one incident, from Mikesh’s careful life, which landed him in court for a criminal offense.

“A buddy and I hid the car of a guy who was just a little too fond of it.”

Mikesh was eighteen. The car was a Mustang, the owner Bill White. While his accomplice had gone with White into the house to watch the taped highlights of the 1985 football season where Bill had played fullback and his friend a left tackle, Mikesh drove the Mustang to the parking lot of the hair salon favored by the town’s oldest ladies and parked it there, underestimating the frenzy and the wrath of its owner once he found it gone. One night in jail and two levels of reduced charges later Mikesh paid his fine and spent his summer before university on probation, doing community service.

“There aren’t a lot of people in this county who have a vehicle theft on their record.”

“And not one who was charged for such a stupid reason.”

“I wouldn’t know anything about that. A record is a record, and I’m just trying to get the report for this death complete and clear. A lot of people are interested in this man.”

“I’ve told you what I know.”

“Does your boss over at the community college know about your record, or the state employment people?”

“We’re talking about Calmar, Iowa. Anybody who has lived there more than fifteen minutes knows the story, including the color of shirt I was wearing when I walked away from the lot of the Twirl ‘n’ Curl and probably, for that matter, the brand of my underwear.”

“The last time I looked, your boss doesn’t live in Calmar.”

“What does that have to do with what happened in the fog last night?”

Fox paused. “Maybe nothing. I’ve got to get the facts, got to be sure I understand my sources.”

“Seegmiller said you are still investigating out at the scene.”

“We’re working with the state. You have to check everything out.” Paul Fox picked up a paper clip and tapped it on his blotter. “Make sure in the final report every t is crossed, every i dotted. That’s my plan, so you may need to come in again. You’ll probably need to talk to state investigators.”

The law enforcement center lot was gray with thinning fog as Mikesh, zipping up his Carhartt, walked across the asphalt. Unhappy that he seemed to be the careless driving suspect in a stranger’s death, and surprised at how deeply the sheriff seemed to be invested in proving his guilt, Mikesh hoped he was on his way home, but he was greeted by me, walking toward him from between the cars, offering my hand.

“Are you Arnold Mikesh?” I asked. “I’m Tom King, Joshua’s brother.”

Okay brother, sister reader. I have already told you I’m the brother of the dying man. What you don’t know is that I am not just Josh King’s brother, but his twin, the fraternal twin, conceived on the same occasion, only six minutes his junior in entering the cold December air of Northeast Iowa. Ever since Josh left college his main nickname for me has been “Diddy Mouse,” which he told me meant “twin.” That, at least, is was what it meant to Josh. In the last few months before he died, Josh had some fun with my given name too, sometimes calling me ‘Tom-Tom,’ saying I would be the Spirit’s drum.

If my delay in this information makes you suspicious, excellent. It’s smart to be skeptical. Something as basic to your wellbeing as water, administered the wrong way, say in a blinding fog, or the bath into which you pass out from having too much drink—can kill you. It’s wise to be suspicious. If you are, you know that I am too close to my brother to tell his story with the detachment you can trust. Better that you get it through the somewhat surprised eyes and ears of one who is just as new to Josh King as you. Hence the tale of Arnold Mikesh. Hence my role as reporter and stage manager. I talked Mikesh into being the star witness of this account. Eventually that meant going over the whole sequence of events that Josh’s accident started in motion. This involved some very long talks. The first began outside what most residents in Decorah call “the cop shop.”

Surprised by my parking lot introduction, Mikesh was flustered as he returned my shake with the grip of his beefy hand. “I’m sorry . . . sorry about your brother dying.”

Mikesh is more at home with empty hallways and feeding cattle than small talk. Not comfortable in this kind of conversation, he was distracted, studying me, trying to imagine what my brother might have looked like when standing and chatting, realizing that even though we were not identical (which we are not) the resemblance was strong.

“Thanks.”

I didn’t know where to begin, myself. A phone call in the night. A long, slow drive from Des Moines. I sat in the back, next to my mother Maria, with our friend Simon at the wheel. In this strangely formal, but necessary arrangement we drove north, white fog in the headlights. Stumbling around our brains were questions with a hand out for answers that remained short on offer. At our destination was a quiet hospital room where Josh’s broken body lay beneath a green sheet, folded back at his groin for the three of us to identify him. Blood had been washed from him, but the crown of rips in his scalp where he broke through the windshield glass were the same raw color as the stew beef in a supermarket meat counter. His abdomen was torn, and ringed round with a purple bruise where the roof and dashboard had clamped him like a vise. And all I could wonder, as I stood and stared at the battered remains of my brother, was what I would next make of my life.

“You were there. You know what we had to look at,” I told Mikesh.

“It was a bad accident.”

“I wanted to thank you for what you did. You probably were not the first person to drive by. No one else stopped.”

“It was quiet the whole time I was out there. There weren’t a lot of people on the road. I was violating a travel advisory even getting into my truck.” Mikesh was thinking about Paul Fox’s questions, the sheriff’s attempt to place him at the scene at the time of the crash. The quiet of that road did make him the only current suspect if you were looking for one. But standing there on the asphalt, looking at Arnold Mikesh’s square, vulnerable face, I didn’t suspect him of anything criminal. Not for a heartbeat.

“I’m sure that’s true. My brother wasn’t good with directions. He might have been coming to Decorah. We don’t know. He rarely drove. I’ll have to admit to you that he wasn’t very good at keeping his mind on the road. He ended up not watching his speed, making mistakes.” Josh’s list of mishaps was long: a mailbox knocked sideways, missed turnoffs, driving on the wrong side of the centerline, passengers white-knuckled on a curve. By the time I was working with him, we always arranged to have someone else at the wheel if Josh needed a car. He was not born to drive. With age, his distraction and helplessness behind the wheel got worse instead of better.

“As for this journey last night, we didn’t know he was gone. The call from the authorities woke us. Nobody knew Josh was away or why he would have left. All the way here we kept wondering how we let Josh slip away before dinner without any of us knowing he was gone. We each felt part of the blame.

“But I heard from the deputy that my brother was still alive when you got to him, that you talked to him.” I hoped Mikesh could dispel the mystery. “If you don’t mind, I’d like to hear what he said. Could I get you a cup of coffee?”

Mikesh and I walked to a place just up the hill, on the corner of Decorah’s main business street. The college kids with their laptops were away on break, so the coffee shop was nearly empty. Coming in from the damp, the warmth, the strong smell of freshly ground dark roast, and the roar of the espresso steamer felt good. Near the counter four women more Mikesh’s age than mine were leaning over their lattes, catching up on the week, their eyes checking us over when we entered. A pair of retirement-aged men sat at one of the booths. I got two filter coffees and we took a table at the far back.

“I’m sure you don’t like to think about it, but it would mean a lot to me, and to the people around Josh, to know how he died.”

In the last few months before the accident, my brother talked quite a bit about his death. Josh was attuned to a world whose existence I often questioned. He said plenty that I let pass unconsidered. The sudden prospect of a future without him left me clutching for any words of his that I had missed.

“I can see that.” Mikesh wondered who the “people around Josh” might be: somber Christians, women in trippy flowered dresses, or Latino meth runners. So far, in Arnold Mikesh’s short introduction to the world of Joshua King, the reports were contradictory.

Mikesh needed encouragement. “According to the deputy, he was still able to speak. Did he say anything I could relay to his Shekinah followers?”

“Who?”

“Shekinah. That’s the name of the group Josh led.”

“What’s the word again?”

“‘Shekinah.’ It means ‘where the Spirit dwells’ or ‘Spirit in you.’”

Mikesh squinted in concentration. “I think that was one of the last words your brother said. The word, it started with that “shh” sound. ‘Shekinah, take my spirit.’ I’ll bet those were his last words.” Mikesh felt tired, thinking of Josh dying with this antique word, like a well-worn rosary, on his lips.

Mikesh told me what he remembered: Josh’s attention to the light, his feeling alone, “join in infinity,” “comfort my mother.” I had him go through it all. Did he remember the tune Josh was singing, did Josh say anything about where he was going? Did he show any emotion? We were talking about my twin brother, the person to whose body I conformed even before we were born.

“Do you know anything about Shekinah, Arnie?”

Mikesh shook his head. “I didn’t know enough about it to recognize your brother when I was trying to help him last night, or the word he was trying to say, if that’s any indication. He asked for my name, but he didn’t live long enough to tell me his.”

“People will tell you that my brother started something that was all about him, that he was the whole show.” Mikesh recalled Seegmiller’s words: Josh as kingpin in a cult of drug runners. “But I don’t believe that. My brother was pointing to something within him but more important, something beyond himself, something that he believed includes you.”

I sat at a coffee shop table trying to explain my brother, while he lay dead in a hospital room down the road. The image of that fought with others: Josh’s face animated with the message he carried, Josh’s hands on an old woman’s shoulders, Josh helping hold the oven door as someone pulled out a tray of loaves, Josh’s voice when he called me “Tom-Tom.”

“He was in shock, and only partly conscious, but didn’t you feel the way he reached out to you?”

“What do you mean?”

“He asked your name. He asked you to comfort my mom.”

“True. That rattled me.”

Mikesh’s reaction was not unique. People were unsettled by the effect my brother had on them. What he said could jar you. Some got angry and turned that against him. Those people and the media saw my brother as a wolf. They circled the wagons, protecting themselves and their flock against him.

I, your story teller, have to admit that Josh had finally unsettled me, too. I worked as a contract archeologist through fall 2007, but after that digging season ended, I moved in with Mom and Josh. More than moved in. After I’d filed my final reports, I helped Josh with his work and decided that from then forward I would divide my year that way. I wished I had a way to tell Mikesh, over coffee, that stepping back into the long shadow cast by my twin brother after having freed myself of him for ten years was neither automatic nor wholly pleasant. It threatened my pride. Deciding whether I was going to continue that work now that Josh was dead was the next issue to face: once the shock passed and the grim business of my brother’s death got completed. That morning in the coffee shop, I had little to offer but questions.

“The people who followed Josh are going to want to know about what you saw and heard. It’s going to sound crazy to you, but those people are very definitely going to want to hear from you whether you saw my brother die, whether he quit breathing.”

While I pictured the faces of the ones who were not going to believe, would never believe Josh was dead, the thought at the front of Arnie Mikesh’s mind was just the opposite: remembering the feeling of his fingers in the airway of my brother’s mouth after he quit speaking, and the silence that pounded in Mikesh’s brain after that last breath. Josh’s dying moment was not an experience Mikesh wanted to speak about to a group of religious fanatics, much less think about himself.

“My mother and I don’t care about an autopsy. We want to bury Josh and move forward. But the sheriff says it has to happen. He feels there could be alcohol or drugs involved. In a way I’m relieved that we are going to get a doctor’s signature on a report that will detail exactly what killed Josh—that it was nothing illegal.”

My phone rang: our friend Simon. I told him where we were, and soon Mikesh, heading back to the parking area, felt my hand—the unfamiliar hand of the dead man’s brother—on his back, guiding him toward a pair of people. One was my mother, Maria, and the other was the bearded man who Mikesh saw when he stumbled into the Sheriff’s office: Simon Peña, Josh’s assistant. Standing outside in the cold, looking into Mom’s splotchy face, Mikesh told the story again, thinking about my brother’s last request: “Comfort my mother.”

“You are sure he didn’t say anything else?” Peña pushed. “You are sure he didn’t say why he was on that road or why he went off it? Something maybe you forgot?”

Mikesh could taste his dislike for Peña. He thought back to what he saw in the sheriff’s office: this man saying he didn’t know what Josh was doing on that road. Peña had nerve to press Mikesh on the same question.

“No. I remember it. I wish I could put it more out of my head.”

Mom placed her hand on Mikesh’s arm. “Of course that’s how you feel.” Mikesh looked into her face: a fifty-one-year-old woman, with the nylon collar of her jacket turned up against the damp, her eyes puffed up from crying, and her sandy hair flat on one side. Her tousled appearance made Mikesh warm to her. She was fingering the zipper of her jacket, where the tab on the slider had broken. And Mikesh heard her give the first sensible judgment he’d heard about the accident: “It was weather, Simon. Bad weather took Josh.”