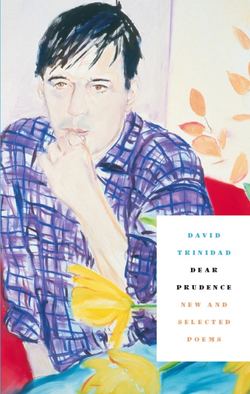

Читать книгу Dear Prudence - David Trinidad - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMOTHERS

When Wanda Hoyt converted her garage to a ceramics studio, rows of chalk-white figurines—clowns, angels, nativity scenes—waited to be painted and glazed in her kiln. The Hoyts had the only color TV on the block; every year we’d watch The Wizard of Oz at their house.

Mrs. Boyer claimed our cat leapt off the fence and attacked one of her toddlers. My mother tried to reason with her, but an argument ensued and Mrs. Boyer threatened a lawsuit. “Hysterical” is the word I heard my mother use when she described the incident to my father. She and Mrs. Boyer stopped talking, each tensely aware of the other’s comings and goings. Later they made up, right before the Boyers moved.

The day Marilyn Monroe died (I was nine) I saw the newspaper, with her picture on the front page, on Jean Silvernail’s coffee table. Jean was a mysterious housewife, revealed, as I got older, the details of her unhappy past. Because she knew I wanted to be a writer, she bought me a copy of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca. “This is my story,” she said. In high school, when I’d go next door to complain about my father, Jean let me smoke her Virginia Slims. I’d leave as soon as her husband, a contractor, pulled his truck into their driveway. After she divorced him, she changed her name to Deveraux.

Shirley Goode, my mother’s best friend, let me borrow her World Book Encyclopedia (a volume at a time) for school reports. Her own sons, she’d wistfully say, seldom touched them. One summer evening, the Goodes (who’d immigrated to Los Angeles from Canada) taught me how to play Michigan Rummy, using pennies instead of poker chips. I’d never had so much fun. Shirley chain-smoked Marlboro Reds and drank Cutty Sark, and had a tiny TV on her kitchen counter, which she watched as she prepared meals. Later in life her gambling got out of control—but she won big, I was told, finally won big. The last time I saw her, at my mother’s funeral, she was suffering from a fungal brain disease.

Straight-laced and formal, Lauren’s mother, a teacher, was one of the few single parents in the neighborhood. Instead of a lawn, she put a cactus and rock garden in their front yard. When my wagon ran off the sidewalk and crushed some of the plants, Lauren’s white-haired grandmother, whom they called Boo, ran out of the house and screamed at me.

Once when I went over to Hal’s, his mother was dancing to “Walk Right In” in front of a mirror in their living room. The Weilands owned an aluminum Christmas tree—the first I saw—which they decorated with all red balls and lit with a rotating color wheel. Mrs. Weiland opened Hal’s bedroom door without knocking, discovered us with our hands in each other’s underwear. I was afraid she would tell my mother. Suddenly Hal didn’t want to hang around with me anymore.

Mary DeMario (my friend Nancy’s mother) took diet pills and did her weekly grocery shopping in the middle of the night, at a 24-hour market. Known as a “kook,” she’d eventually have breakdowns. Two strong memories of her both involve water. The first: Stuck inside on a rainy day, Nancy and I sit at their kitchen table, coloring. Mary reacts, excitedly, to news on the radio: a local boy drowned when water suddenly flooded the drain tunnel where he was playing. The thought fills me with panic and dread—a sick, breathless feeling at the bottom of my throat. The second: Because it was cheaper than carpeting, the DeMarios had had their floors laid with linoleum. One day, to avoid sweeping and mopping, Mary drags furniture into the backyard, then sprays down the living room with the garden hose.

Vera Holmes lived next door to the DeMarios. She and the woman next door to her, Mrs. Scott, joined Weight Watchers (new at the time) and everyone commented on the pounds that they lost. Vera’s husband was a policeman. After I was raped, my mother showed him the credit card receipts we’d found hidden in my guesthouse. He looked into it, disclosed that the card had been stolen from a woman in upstate New York. She too had been assaulted by Nick, but chose not to report it. He said I was in a “tricky” (meaning humiliating) position, and advised us not to pursue criminal charges.

Kathe Lindsay (a year and a half older than me) battled cancer from the time we were in junior high until she died in the early ’80s. Newly sober, I accompanied my mother to her memorial service. Kathe had worked in the library at Cal State Northridge; I’d say hi to her when I went there to listen to recordings of Anne Sexton and Sylvia Plath. A few years after her death, shortly before I moved to New York, I published a poem in The Jacaranda Review. The journal was put out by UCLA’s English Department, where Kathleen, Kathe’s mother, worked. Kathleen called my mother and said, “I’ve just read one of David’s poems.”

Priscilla Moran bought her daughter every Barbie outfit, and watched over them like a hawk. The day Linda opened a black wardrobe case and displayed the doll (blonde ponytail) and all her clothes, she gave me one of the booklets (she had dozens of them) that came with every costume: colorful drawings of Barbie’s ensembles and accessories. That night I studied each picture, read each description. The next morning, Priscilla knocked on our side door and spoke to my mother, asked for the booklet back. But I’d already committed those images to memory: the pink negligee, the yellow bathrobe, the glamorous black nightclub dress....

Odessa Miller, who was older than other mothers, had a dry sense of humor (and cackle to go with it) and little patience for her rotund husband’s religion, Mormonism. I was friends with her daughter Marsha in high school. Marsha had dated my brother, but broke up with him because, like my father, he had a bad temper. Once, stoned on marijuana, I crawled laughing through Marsha’s bedroom window. Soon after graduation, she moved to Utah and married a Mormon. To earn spending money when I was in college, I worked part-time as a PBX operator at the answering service Odessa managed.

Scott Small’s mother was never home. His older sister was taking hula lessons: I can still hear the lyrics of “My Little Grass Shack,” which she played over and over on her portable phonograph. I persuaded Scott to sneak her Barbie Queen of the Prom game out of his house and bring it to mine; we set it up on my bedroom floor. The board had the same graphics as the booklet: Barbie in a blue party dress, in a flowing pink evening gown. We’d just started to play when my mother came in the room. She saw which game it was and made us stop, made Scott take it home.

Melanie Brown complained that her mother would give money to any solicitor who rang their doorbell. Mrs. Brown complained that their houseguest, a friend of Melanie’s, used up all the hot water taking long showers. She was separated from Melanie’s father, who was black, a serviceman stationed in Victorville, California. Melanie and I were friendly for a while in high school, but she hurt my feelings when she said that I was a racist because I didn’t know enough black people.

Mrs. Messerschmidt could have become an opera singer (she had had talent). Instead, she’d ended up in the suburbs, with two teenage daughters, a husband in construction, and a job as a secretary at one of the factories below Plummer. Her brunette hair always in a perfect bubble (she had it done once a week), she’d sit at the kitchen counter inhaling menthol cigarettes while her nails dried. Everything in their living room—furniture, carpet, curtains—was white. No one spent time in it. Janice wanted to be a fashion model; her younger sister Vicky, a roller derby star. I felt closer to Vicky, who seemed to understand (and believe in) my dream of becoming a writer. I related to her, in vivid detail, the entire plot of Valley of the Dolls. One Saturday night, I went with the Messerschmidts to the Winnetka Drive-In, to see Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (I’d lied to my mother about which movie.) Though the swearing and flare-ups were riveting, the dialogue went over my head. I introduced Vicky and Janice to Mark, my friend in the housing tract on the other side of the wash. Mark’s father was a security guard at location shoots; he’d taken Mark and me to see an episode of Adam-12 being filmed. His mother also smoked menthols: Alpine—the strongest cigarette I ever tasted. I loved the way she made scrambled eggs (with lots of milk and cheese); when I told my mother this, she acted miffed. Mark’s mother worked as a cashier at K-Mart. The summer after we graduated from junior high, Mark and I would take her car from the parking lot (he had a secret set of keys) and drive it around the neighborhood. I was always anxious that we’d get caught. Once high school started, Vicky, Janice, Mark, and I began playing hooky. We’d go to the girls’ house, watch soap operas and smoke. Home from such a day, I found my mother at the screen door, furious (the school had phoned about my absences). Helpless, I confessed. What else have you been up to? I told her about Mark’s and my joy rides. She meted out my punishment (grounded for weeks), then said she intended to call my friends’ parents; I pleaded with her not to. The three of them got in trouble, and stopped talking to me. Despite Mark’s infraction, his parents bought him a car, a green station wagon. For the remainder of high school, whenever they passed me walking home, they’d lower the car windows and tauntingly call out my name. Sometimes Mark would honk the horn. I waited ten, fifteen, twenty minutes before leaving school, tried taking different routes, to avoid them; invariably, they’d drive by and yell. Their new friends, kids I didn’t know, happily joined in. I’d focus on Vicky, sitting stiffly in the middle of the back seat, staring straight ahead as the others shouted, as the station wagon sped down the street.