Читать книгу Youth on Screen - David Buckingham - Страница 16

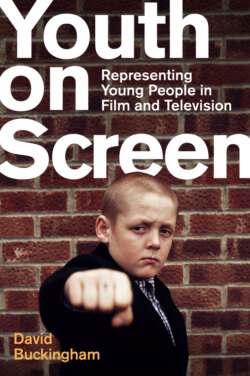

Violent Playground

ОглавлениеThe final film I want to consider here was made a few years later and deserves a little closer attention. Violent Playground, directed by Basil Dearden and produced by Michael Relph, was released by Rank in 1958. It was the first of a series of ‘social problem’ films made by Relph and Dearden around this time, which include Sapphire (1959), about race relations, and Victim (1961), about homosexuality. These films were seen by their producers as an attempt to fulfil the ‘social and educative responsibilities of film’: a group of forty boys on probation was taken to see Violent Playground to give them ‘a lesson on the futility of juvenile delinquency’.19 Despite such liberal intentions, these films have often been criticized for their allegedly staid and conservative approach to social issues – although, at least in this case, I would argue that the film is rather more ambivalent and contradictory than this would imply.

The film’s central character is a detective, the appropriately named Jack Truman, played by Stanley Baker. At the start of the film, Truman has been investigating the activities of an arsonist known as ‘the Firefly’, but he is reluctantly reassigned to the Juvenile Liaison division – which provokes a good deal of ribbing from his colleagues. Truman follows up a story about seven-year-old twins, who have been caught swindling and stealing from local shopkeepers, and soon encounters their older sister Cathie Murphy (played by Anne Heywood) and their brother Johnnie (David McCallum). The children’s parents are absent, and Cathie is their main carer, although Johnnie is the leader of a street gang which controls the neighbourhood. Despite her initial resistance, Truman successfully encourages Cathie to send the children to a local youth club, and he gradually becomes romantically interested in her. However, the ongoing investigations into the Firefly come to focus on Johnnie. When Johnnie is refused entry to a smart hotel – and is mocked by the gang – he decides to target it. When the police arrive, there is a sequence of chases across the city, in which Johnnie runs over and kills Alexander, a Chinese laundry worker who has been following his orders and carrying out the arson attacks. The film culminates in an extended final sequence where Johnnie holds a classroom full of children hostage with a machine-gun, using them as human shields: he apparently shoots one dead, although the child later recovers. Through Cathie’s intervention, the children are eventually freed, and Johnnie is taken away by the police to face manslaughter charges.

Violent Playground combines aspects of police procedural and action drama with elements of documentary realism. The film is set in Liverpool – although none of the characters speaks with an authentic Liverpool accent (the Murphys are Irish). Nevertheless, it does make striking use of real locations, not least the densely populated working-class council estate (a public housing project called Gerard Gardens) where the Murphy family lives. The street scenes show the continuing ravages of Second World War bombs, with groups of children running wild across urban wastelands. As with Boys in Brown, the film has a didactic element: it was apparently based on an experimental juvenile liaison scheme run in the city, and it both explains and demonstrates (for instance in the youth club scenes) how the system operates. The key concern is that younger children (such as the Murphy twins) will gradually work up from petty crimes such as shoplifting to more serious crimes (such as those committed by their brother). The aim of juvenile liaison, Truman is told, is to catch such children before they commit their second crime. According to a statistic shown on the film’s original opening titles, 92 per cent of young people reached by Juvenile Liaison Officers did not subsequently reoffend.

The film offers several potential explanations of the causes of delinquency. On one level, there is an implicit recognition that it is more likely to occur in conditions of poverty, although this is not directly addressed. More explicit is the fact that both the children’s parents are absent: the father, we are told, is a stoker, while the mother seems to have absconded to London and possibly remarried. At one point, Johnnie complains to Truman that there are no jobs for people like him, offering a further sociological explanation. Shortly afterwards, however, Truman follows him to their flat, where members of the gang are dancing to records – and specifically to the rock-and-roll tune that plays over the film’s opening and closing credits. The lyrics emphasize the connection between rock music and violence: ‘I’m gonna play rough, rough, rough – I’m gonna get tough, tough, tough’. Johnnie throws himself into the dancing with wild abandonment, although his repeated looks towards the uncomfortable Truman also reflect a kind of homoerotic exhibitionism. Meanwhile, the twins look on, trapped behind a chair placed on a table, which resembles a kind of cage. Eventually, the group surrounds Truman, still twitching along to the music like a group of hypnotized zombies. The scene dramatizes contemporary anxieties about the harmful influence of pop culture to a level of almost comic absurdity; and this association is reinforced later in the film, when Johnnie is given the machine-gun, carried by one of the gang members in a guitar case.

Ultimately, however, the main source of Johnnie’s delinquency lies elsewhere. The local priest (played by Peter Cushing) eventually explains to Truman that Johnnie had saved one of the twins from a fire when he was younger, winning considerable acclaim from the local people. According to the priest, Johnnie now feels compelled to re-create the scenes of his former glory – and thereby recall a status that he cannot otherwise attain. As this implies, the primary explanation for delinquency, in Johnnie’s case at least, is psychological rather than sociological – a matter of individual pathology rather than social environment. This is reinforced by the ways in which he is framed: we first see him only in a back view, and there are several instances (not least in the dancing sequence) where he is lit and filmed (from low or titled angles) in almost expressionistic ways more characteristic of film noir. This is carried through into the final scenes in the school, where the style seems to abandon any pretence at documentary realism and approaches that of a psycho-killer movie. Yet, while Johnnie is undoubtedly charismatic, he is also shown to be weak (as when he is mocked by the gang for being refused entry to the hotel), and his desperation ultimately borders on a kind of personal psychosis: as with Cosh Boy, the film works hard to resist any potential identification.

To some extent, Violent Playground seems to endorse a liberal approach to the problem of delinquency, although there are certainly limits to this. At the start, Truman favours ‘walloping’ (beating) miscreants, but he is quickly brought round to a less disciplinarian approach. Both Cathie and Johnnie initially resist his do-gooding overtures. She comments sarcastically ‘You’re going to put all this right, with your psychology and your big talk’; although, when the twins do attend the youth club, she seems impressed by their enthusiasm. There is a sense that Johnnie likewise might be capable of redemption. In one scene, he returns to the athletics club where he was formerly a star runner, although he is too out of condition to win the race.

Johnnie’s running coach here is also the head teacher of the twins’ school, a genial Welshman with the (not coincidental) name of ‘Heaven’ Evans. In earlier scenes, Heaven is portrayed as a powerful defender of his students’ interests: he scolds one of his teachers for boring them and warns Truman against ‘fighting a war against my children’. All children are basically good, he assures Truman: they are not ‘delinquents’. The priest also resists the intervention of the police and their claim that they ‘know better how to look after children’: he supports Cathie and defends Johnnie, with whom he appears to be making progress just before the net closes in on the Firefly. Even so, as the narrative proceeds, Johnnie evades or rejects these more liberal approaches; and, when the priest tries to intervene in the final siege, Johnnie pushes him off a ladder.

At the same time, there are also contrary voices. In one key scene, Truman tells his police colleagues that Johnnie is ‘potentially a good boy’, but his views are contested by the chief inspector. ‘Everyone’s potentially a good boy,’ he says. ‘Haven’t we had enough of those crazy mixed-up kids who go around bullying, ganging up on people, beating up old ladies?’ Truman protests, but the chief inspector continues: ‘I’m a policeman. I’ve got respect for the law. I know it isn’t fashionable. But let’s spare a thought for the old lady. For you and yours. If these children want to try living outside the law, they can pay the price if they’re caught. I’m tired of the tough guy fever.’ He claims that the juvenile liaison approach won’t make any difference to such young people – ‘They’re like lepers, only they don’t warn you with a bell.’ Truman resists this, claiming that what will make the difference is ‘what always has – a lot of mum and a little bit of dad’. This is clearly framed as a debate: yet, while Truman is the sympathetic hero of the film, the chief inspector is shot in close-up at the front of the frame, appearing to privilege his perspective.

The debate is cut short at this point, but it returns implicitly at the very end of the film. The police initially attempt to resolve the situation by force, but this proves impossible. Cathie agrees to go into the school to rescue the children on the basis that two ambulances will be sent – one for the injured child and one (we assume) for Johnnie. However, the priest tells Truman that he has to ‘do his duty’. When the siege is ended, Cathie is furious to find that there is only one ambulance: Johnnie is sent away in the police wagon, not as a sick individual in need of help but as a criminal. While the child whom he apparently shot is revealed to be suffering from ‘shock’, and while he will face only manslaughter charges for killing Alexander, it’s clear that he must be punished. As Truman concludes, ‘You can feel too sorry for Johnnie.’ In one of the closing scenes, Cathie seems to endorse his approach: there is a hint that there might be some romantic future for them, but ultimately (like Mary Magdalene) she kisses his hand and then crosses the street to where the priest is waiting in the church.

The critic John Hill reads these scenes as evidence of the film’s endorsement of conservative, even authoritarian solutions to the ‘problem’ of juvenile delinquency.20 In my view, it is rather more ambivalent. The film begins and ends not with Johnnie but with the twins. In the closing scenes, after the other children are collected from the school by their mothers, the (parentless) twins sit waiting on the stairs. Truman takes their hands and, together with Heaven, arranges to feed and look after them. Johnnie has to be punished, but the twins can be educated and thereby saved from a life of crime. There is no redemption for Johnnie, but the solution may lie in the next generation: if they can learn that the likes of Johnnie are not to be seen as role models, there is hope that the problem may be overcome. In the very last scene, we see Truman take the hand of a young black or mixed-race child whom he has prevented from stealing from a market stall. While far from radical, these conclusions imply a liberal, reformist approach rather than a purely disciplinarian one, and certainly nothing of the Cosh Boy variety. As Tony Blair himself might have put it, the film calls for us to be tough on crime but also tough on the causes of crime – an approach whose effectiveness certainly remains open to debate …