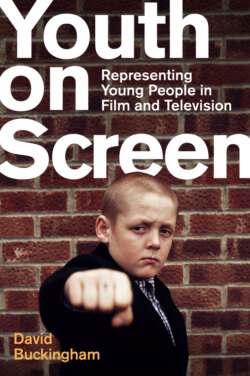

Читать книгу Youth on Screen - David Buckingham - Страница 7

Troubling ‘youth’ and ‘screens’

ОглавлениеThe idea of youth has a considerable symbolic potency. It is typically associated with notions of energy, idealism and physical beauty; yet it is also frequently represented as both troubled and troubling. The term itself has ancient origins, but modern ideas of youth owe a great deal to the work of the social psychologist G. Stanley Hall. Writing at the start of the twentieth century, Hall regarded youth (or adolescence) as a particularly precarious stage in individual development. It was a period of ‘storm and stress’, characterized by intergenerational conflicts, mood swings, and an enthusiasm for risky behaviour. From this perspective, the discussion of youth often leads inexorably to concerns about drugs, delinquency, depression and sexual deviance. Hall’s symptomatically titled book Youth: Its Education, Regimen and Hygiene (1906) includes extensive proposals for moral and religious training, incorporating practical advice on gymnastics and muscular development, as well as quaint discussions of ‘sex dangers’ and the virtues of cold baths.

Youth, then, is popularly regarded as passing stage of life. Young people are typically seen not as beings in their own right in the present but as becomings, who are on their way to something else in the future.2 Adults may pine for their lost youth, or create fantasies about it; but youth is only ever fleeting and transitory. Yet, in all this, there is a risk that the child may not successfully manage the transition to what is imagined to be a stable, mature adulthood. As such, at least in modern Western societies, youth is often regarded as a potential threat to the social order.

Of course, there is considerable diversity here. ‘Youth’ is not a singular category but one that is cut across by other differences, for example of social class, gender and ethnicity. Constructions of youth are historically variable and often reflect wider cultural aspirations and anxieties that are characteristic of the times. Both the representation and the actual experiences of youth can vary significantly between national settings; and, as anthropologists remind us, if we look beyond Western industrialized societies, our conceptions of youth may have very little relevance. Like gender, age can be seen as something that is ‘performed’ in different ways and for different purposes in different contexts.3 To some extent, as the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu has asserted, ‘youth is just a word’.4 Even the words that appear to mean similar things – ‘teenager’, ‘adolescent’, ‘juvenile’, ‘young person’ – tend to carry different connotations and to serve different functions.

Over the past seventy years (the period covered by this book), it’s possible to identify a continuous drawing and redrawing of boundaries, both between childhood and youth and between youth and adulthood. The question of where youth begins and ends has become increasingly fraught. Some argue that childhood has increasingly blurred into youth – provoking anxieties such as the continuing concern about the ‘sexualization’ of children. Meanwhile, youth itself seems to be extending: young people are leaving the family home at an older age and ‘settling down’ in terms of stable jobs and relationships at a later point. Many official definitions of youth now extend into the late twenties, and in some instances well into the thirties. New categories – such as ‘tweens’ and ‘adultescents’ – have emerged in an attempt to pin down what appears to be the changing nature and significance of age differences.

This blurring of boundaries is also increasingly apparent in the marketing of media and in media representations themselves. The appeal of what were once seen as ‘youth media’ – computer games or rock music, for example – increasingly seems to reflect a broadening of the youth demographic. ‘Youthfulness’ is something that can be invoked, packaged and sold to people who are not by any stretch of the imagination any longer youthful. Contemporary media marketing seems to imply that you can be ‘as young as you feel’5 – although young people themselves may also resent adults trespassing on ‘their’ territory and develop new ways of excluding them.

This is equally evident in relation to film and television. Scholars have tied themselves in knots attempting to define ‘youth film’. The films and TV programmes I consider here all feature young people in central roles, but not all of them would be generally categorized as ‘youth films’ or ‘youth TV’. However, this begs the question of how we might determine what a ‘youth film’ actually is in the first place. Is it a quality of the film itself, or of its intended or actual audience? Not all films about young people are necessarily made exclusively, or even primarily, for a youth audience; nor is ‘youthfulness’ (whatever that is) necessarily the defining quality of such characters, or even a major theme of the films in question.

‘Youth films’, we might argue, are those which tell us stories specifically about youth itself – and, very often, about the transition from youth to adulthood. However, most of them do so for audiences of both young people and adults. Indeed, it’s possible that a great many films that we might perceive as ‘youth films’ implicitly view youth from the perspective of adulthood. This is the case, I would suggest, not just when it comes to some of the well-known ‘classics’ I consider here, such as American Graffiti and Badlands, but also with allegedly juvenile comedies such as American Pie and Porky’s, which also attract substantial adult audiences.

The same difficulty applies to ‘youth television’, or what is often called ‘teen TV’. While young people have always been a key audience for films in the cinema – and became even more important during the 1950s and 1960s, as the adult habit of regular cinemagoing fell into decline6 – they have generally been much more elusive when it comes to television. Programmes targeting teenage audiences have an uneven history: although there are some interesting precursors, teen-focused dramas did not fully emerge until the rise of specialist cable channels in the 1990s.7 Yet children and young people have always watched programmes intended for a general ‘family’ audience, while adults make up a significant proportion of the audience for what might be categorized as ‘youth TV’.

Amid this complexity, my approach here is fairly straightforward. My title is Youth on Screen, not ‘Youth Film’ or ‘Youth Television’. The films and programmes I discuss all focus primarily on young people, and many of them explore the transition between youth and adulthood. They are by no means intended only for ‘youth’ audiences, however we might identify or define that. Yet, implicitly or explicitly, all of them are about youth: they raise questions about the characteristics and condition of youth, about the place of youth in the wider society, and about the meaning of ‘growing up’.