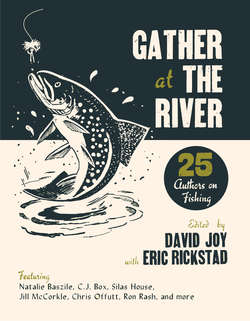

Читать книгу Gather at the River - David Joy - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe Mullet Girls

JILL MCCORKLE

Every summer my family spent a week at the beach—for years going to the same house at Holden Beach, N.C. This house had (pre-Hurricane Hazel, 1954) been set back from the ocean a couple of rows but now in the late ’60s and early ’70s was oceanfront, high tide reaching and lapping beneath the wooden steps leading up to the screened-in porch. My dad’s best friend, who owned the house, continued to pay a meager amount of property tax (seventy-odd cents a year) on the land that was already submerged. In spite of many efforts, sandbags and sea oats, the ocean has continued to devour this small part of the world such that what I remember is far removed from what now remains.

I had just turned thirteen and for the first time was dividing my days between my mom and older sister, who liked to swim and sun read, and my dad, who spent the entire day either fishing or getting ready to fish. The house was full of people that summer, various friends and relatives, our teenage boy cousins we didn’t see very often. We spent a lot of time playing cards, our cousins’ united goal being to get us to say “the ace of spades,” which sent them into convulsive laughter about how we sounded just like we had stepped out of The Andy Griffith Show. They were, after all, from Maryland, which was the North by our standards.

Out of the blue on one of those afternoons, two women in bikini tops and short shorts appeared at the screen door. They called out my father’s name in shrill girlish yoo-hoos. “Johnny! Oh, Johnny!”

We all froze. Even though the whole exchange took only a few minutes, it became the event of the week and one we referred to often for years after. We called them the Bathing Beauties, the Beach Walkers, the Mullet Girls.

Any other year and I would not have been the one to go to the door. I would have been with my dad fishing. I was his fishing buddy (or at least he allowed me to think that); his surrogate son. I prided myself on being the daughter who could touch anything stinky and slimy without flinching. I reached into the rich loamy earth and plucked my own fat squirmy bloodworm from the plastic carton. I speared, twisted, and looped it on my hook, wiped the blood and goo on the butt of my swimsuit. I had spent hours learning how to cast, my thumb poised and ready to slow the momentum smoothly instead of giving it a jerk that would result in my dad having to sit and unwrap and untangle—something he had already done many, many times.

Once we caught a spiney sharp-toothed fish, his struggling mouth like serrated scissors. It looked prehistoric, spiked and dangerous, and I am still not sure to this day what kind of fish it was. My dad gave up trying to extract the bloody hook where it was firmly wedged and simply cut the line up close and tossed the creature back into the surf. “Poor old fella,” he said, “his wife is going to be so disappointed when he gets home.” Just the way he said it with such conviction and compassion left me saddened for the rest of the day as I imagined that silver briny body cutting its way against the tide, the hook already rusting. All day I saw him swimming out into the coldest, darkest depths in search of his mate.

The women at the door were as surprised to see all of us as we were to see them. I just stood and stared at them through the dark mesh of the screen. I had seen them earlier as I rocked on the porch and used the binoculars to spot dolphins and the large shrimp boats that were always hovering on the horizon. I had watched them strolling back and forth on the beach, bending to pick up shells in a way that made their shorts ride up even higher. They had stopped several times and peered into the yellow bucket beside my dad’s sand chair, which we had just given him for Father’s Day, curious about his catch. I knew there was probably nothing in the bucket. I knew that he often stopped baiting his hook so that he had an excuse to sit and stare at the ocean.

What I had seen from a distance as the Mullet Girls strolled back and forth were two bronzed bodies in bikinis. Up close they were not at all what I had expected.

“Is Johnny here?” the one with the bobby pinned rollers hidden up under her scarf asked. I did not like the sound of his name coming out of her mouth. It made me mad. It made me feel just as I had as a six-year-old, when, after seeing, The Sound of Music, my dad commented on how pretty he thought Julie Andrews was. I worried for the next few months that my parents would leave each other for Julie Andrews and Christopher Plummer, and there I’d be with eight siblings instead of one. My sister would do okay; she could sing. But where would I ever fit in with that crew?

“Well, is he still fishing somewhere?” This was the short one, her hair bleached to a shade of yellow that would only be considered natural on an egg yolk. She closed one eye against the trail of smoke from the cigarette she held in the corner of her mouth. Her hands, I noticed, were clutching a big canvas bag.

“He’s not here,” I said, hoping that my cousins were hearing their accents, slow and flat even to my ear. The folks from Mayberry sounded like British royalty by comparison. “And I’m not sure where he is.”

“Well, you tell him we were by,” the short one said. “He’ll know who you mean. We promised him some mullet if we had some luck, and, boy, did we have some luck.”

“We’ll stop by after dark,” the other one said, and I stood and watched as they walked down the road to an old blue Chevrolet.

I knew exactly where my dad was. Every day, later afternoon, low, tide, he walked way down the beach to what connected the ocean to the inland waterway. At low tide we could walk across the channel and find live starfish and sand dollars and conchs along the way. He could sit there for hours, just watching the water, tending his fishing pole, puffing on his pipe, sipping a beer. He liked to think about all that he would do when his ship came in—a long, long list—only to make his way back around to say that things were pretty good the way that they were, he really wouldn’t want to change a whole lot. Maybe he’d ask for two weeks’ vacation from his job at the post office instead of one.

He talked about depression long before it was an acceptable thing to talk about, taking great solace in the knowledge that both Lincoln and Churchill had been fellow sufferers. He also found a way to put a positive spin on that condition, saying about at least one acquaintance, “I don’t know that I think this fella is smart enough to be depressed.” He told me how some of the greatest moments of his life were when he fished with my mother’s father long before he had married into the family. How my grandfather had tied a rope to his belt, the other end to a sack of beers which he allowed to roll and wash under the waves where it was cool.

For years my dad had entrusted me with a special assignment. When he left for the point, he handed me an alarm clock with strict instructions that when the alarm sounded I should run to the refrigerator and grab the brown paper bag and run as fast as I could down to his special fishing spot. For a long time I thought I was carrying bait, the bait that would land the huge fish that had just gotten away. What I ultimately discovered was that in those pre-Playmate cooler days, I was making a beer run—two iced Falstaffs wrapped in aluminum foil and swaddled in paper towels in the paper sack. I was a two-legged Saint Bernard. I was part of a legacy my maternal grandfather had started. My dad fancied the idea of Smoky, our black shepherd mix who hated anyone who was not in our immediate family, with a keg on his neck, but by then he had his cooler. And he still had me.

“Who were they?” my mother asked. “Have you ever seen such skimpy outfits?” If there was a flush to her cheeks, it was well concealed by her annual sunburn. Fair and freckled, she was trying to get a tan even if it meant the occasional burn and a dowsing of QT lotion. “And what did they want with Johnny?”

I told her how up close they looked nothing like they did from a distance. They were odd looking. Coarse. Rough and worn out. They were wrinkled like old prunes and they smelled fishy.

“Something’s fishy,” she said, and though I knew it was a joke, I found it hard to laugh. I kept thinking how she had said, “What did they want with Johnny?” Not your daddy, but Johnny, leaving me to feel left out the same way I did when I looked at photographs before I was born: a young family of three, or before my sister; a couple of newlyweds. They had known each other their whole lives; they had dated since they were sixteen. They had been married for twenty years and were in their early forties, and it was the first time since “The Sound of Music” that I had ever really thought of them as people who might attract others, or worse, be attracted to another, especially another who did not resemble Julie Andrews in the slightest.

“One of them had her hair rolled up,” I said. “Where’s she going, Surfside or Van Werry’s?”—the one and only grocery store down near the drawbridge. Everybody else just laughed and went back to playing spades. There was nowhere to go in that neck of the woods other than Surfside Pavilion, a squat, pink cinderblock building with two pool tables and a few pinball machines and a miniature golf course that was always soggy and warped from years of damp salt air and rain.

I had seen girls hanging out of car windows hooting and hollering at boys who stood around outside the pavilion smoking cigarettes and waxing their surfboards. My mother liked to use loud girls who hung out of car windows with cigarettes in their mouths and breasts spilling from tight bathing suits as examples of what not to grow up and be.

“Don’t you ever let me catch you looking like that,” my mother said.

“So should we hide?” my sister asked without cracking a smile. She was sixteen and had far more clout than I did.

We had heard all the stories about what girls NOT to be like. It was for this very reason that we had stopped going to Ocean Drive and Myrtle Beach, which had become a haven for teenagers and college kids who wanted to party, have sex, fall into violent and drunken sidewalk brawls, and enter the shag contests at places like The Pad and the Spanish Galleon, where the music of the Tams and the Drifters and Maurice Williams and the Zodiacs blasted all through the night. People said that you could go to South Carolina and get married, get a drink or two, buy some fireworks, get a divorce and still be home in time for the eleven o’clock news.

Surfside Pavilion paled by comparison, but we had gotten used to it. The quiet; the women like my mother who, if they wore a swimsuit at all, wore a one-piece with boy legs or little skirts. Suits that hid all evidence that children had ever sprung from their bodies.