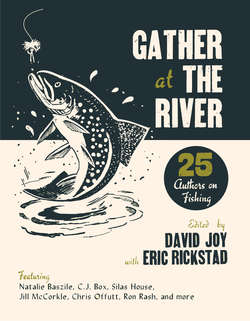

Читать книгу Gather at the River - David Joy - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеGould’s Inlet

TAYLOR BROWN

We rolled up to the beach in a battered Jeep Cherokee, the sandy pavement crackling beneath our tires. My friend Lee Hopkins threw the shifter into park. He was an ace shortstop and near-scratch golfer with summer-blond hair and freckles. Hints of pink showed underneath his clear eyes, like ballplayer’s eye paint. His true love was marshes and streams.

Before us lay Gould’s Inlet, the narrow entrance to the river and salt marsh that divided the island we lived on—Saint Simons Island in southeast Georgia—from the southern point of Sea Island, an exclusive resort where I worked at the bicycle shop, renting beach cruisers to well-heeled vacationers. We were sixteen years old.

The inlet glittered like a long sword under the summer sun, slicing through the soft flesh of beaches and sandbars. A beautiful streak of water, but deadly. The tide roared through here as through a sluice. Old signs, thick with bird droppings, warned against swimming.

Strong athletes, with white teeth and golden arms, had disappeared here. Once, the inlet sucked a pair of doctors out to sea. They spent a whole night in open water, their eyes swollen shut from the salt. They removed their trousers and tied off the legs, like we learned in Boy Scouts, making improvised life vests. Blinded, they didn’t know they were safe until the incoming tide thrust them back on the beach.

Low tide had revealed the vast sandbar jutting more than a mile out from the beach. The very tip of this peninsula verged on deep water—our destination. We lifted the rear gate of the Jeep and chose our rods for the day from the quiver running the length of the interior. We took a five-gallon bucket full of tackle and a red Igloo cooler. The latter was faded the color of an old brick, loaded with ice and bait, bottled water and Coca-Cola.

My father spent much of his childhood on the water in Saint Petersburg, Florida. Skiing, fishing, boating. However, we would not own a boat until later in high school, when one of his friends gave us a hard-worn old ski boat he couldn’t sell. So, the fishing of my youth was mainly this: surf fishing.

We crossed a boardwalk to a strip of soft sand that crunched like snow under our feet. Here, beachgoers lay on their towels, oil-glazed under the sun, their bodies baking like Krispy Kreme donuts. We descended these postcard sands and crossed a wide stream, ankle-deep, at the foot of the beach. This was a minor branch of Gould’s Inlet, dividing the upper beach from the vast expanse of the sandbar.

On the far side of the stream, the sand became immediately darker, harder, rippled by hydraulic action. The ground was strangely cool beneath our feet, as if we were walking on the bottom of the sea. At any time but low tide, we would be.

We walked and walked across this vast desert of sand—wave-ridged, hard as stone, like the surface of an alien world. We splashed through tidal pools, piss-warm, where tiny schools of baitfish shot back and forth in their formations, trapped by the outgoing tide. Gulls wheeled and screamed overhead, trailing us like a shrimp boat. From a distance, we must have looked like bizarre pilgrims, burdened with our jangling array of rods and nets and tackle. Our boonie hats squirmed and flopped in the breeze, trying to lift from our heads.

My feet hurt, hurt, hurt. I was born with clubfeet, my ankles twisted so that my soles met like praying hands. Straightening them had necessitated a slew of reconstructive surgeries—the most recent just three months before, right after school got out. My summer, so far, had been morphine drips and bedpans, sponge baths and paperbacks and balsa-wood model airplanes. A month ago, I had watched my doctor remove a six-inch pin from the heel of my left foot with a pair of vice-grip pliers.

The sand here, hammered into such stony ridges, throbbed through my soles. I focused into the distance, the creamy roll of the breakers, where the sandbar dropped like a shelf into deeper water. The sea looked nearly black beyond the surf, flecked with silver shards of sun.

When I think of the water of the Georgia coast—my home—I think of shadow and murk. Mystery. Four blackwater rivers empty their mouths along the seaward edge of the state, including the “Amazon of the South,” the Altamaha. That mighty river, undammed, is storied for torpedo-size sturgeon and alligator gar—armored fish which slink through the lightless currents like prehistoric relics. Then there’s the famed sea monster of the coast, the Altamaha-ha, which haunts my second novel, The River of Kings.

The Altamaha delivered the alluvium that built these barrier islands, raising them over eons from the sea. The same dark sediment muddies the water here, so that the palm of your hand, spread pale and flat beneath the waves, will disappear just six inches beneath the surface. In the shallows, you never know where your next step will fall. Such water breeds mystery, legend. Fear.

We kept trudging across the expanse, reaching the foamy slurp of the waterline. Soon we were cradled in the surf, belly-deep, casting our lines. White shreds of bait—squid—flew like tiny ghosts from our poles, twisting and fluttering through the air. They landed beyond the shelf of the bar. They sank into the darkness, their pale flesh hiding the stainless gleam of hooks.

Green mountain chains of surf rose before us, again and again, only to tumble and crash in our wake, lathering the sands in foam. Soon my pain began to dissipate. I was lightened. I rode the swells with my hips, bouncing from the bottom in slow motion. I had the strange buoyancy of an astronaut.

In reality, I didn’t care much about catching fish. For me, on the walk out, this outing had ceased to be about fishing or adventure or even friendship. It had become a test. The same as most any outdoor concert or school dance or Boy Scout hike—anything that required me to stand or walk for longer than an hour. I didn’t care about the fish, like I didn’t care about the band or the football game or the destination of the trail. I cared about getting it done, the same as everyone else.

Lee was different. He had come with ambition. He was here to catch fish. He squinted over the breakers, his face freckled and sun-pinked. He had the easy grace of the gifted athlete, which I envied. He seemed born to wield baseball bats and golf clubs and fishing rods. I had watched him knock the red clay from his cleats and lift his Easton Black Magic bat swirling over his shoulder and rope the first pitch straight over the centerfield fence. Meanwhile, I was stuck in right field, last on the batting order.

I envied Lee, but I respected him. We used to play one-on-one tackle football in his front yard, with his father for all-time quarterback. I remember Lee catching an accidental forearm shiver while going for a sack. We were maybe ten. Lee rose grinning, licking the blood from his mouth. You can only love a kid like that.

Still, he wasn’t accustomed to striking out, even if he was up against the ocean. He was getting frustrated. His eyes had turned to firing slits. The muscles flickered in his temples and cheeks. Meanwhile, the sun was beginning to slip, falling slanted at our backs. Soon the tide would rise, slipping over this vast peninsula of sand. It already was. We’d moved our tackle farther up the beach, twice.

Lee reeled in his line. The twin hooks were naked, like steely question marks.

“What you think?” I asked.

Lee’s gaze remained fixed on the surf, the dark valley beyond the breakers.

“Ten more minutes,” he said, rebaiting his hooks.

I shrugged. “Sure.”

Ten minutes. Fifteen. I felt the tide crawling higher up my belly, but I wasn’t worried. The sun had lulled me, the roll of surf. I was not in pain. Still, I was about ready to go. I wanted to get started on the hike back to the car—to get past it.

Twenty minutes. Lee reeled in his line, his teeth gritted. Defeat in his face. I was looking at him, hoping he was ready to leave, when the black antenna of my rod snapped double, nearly yanked from hands.

“I got something, Lee! I got something!”

Lee’s eyes jumped open. He came wading and splashing toward me, holding his rod over the water.

“Big mother!” I told him.

I could feel the strength of the creature through the line. A whip of muscle, cracking with power. The fury of a hooked jaw was wired right into my palms, zero distortion. The fish was talking to me, saying I am deep and mad and strong. The message was wordless and pure.

A swell broke around my chest, that high, and I knew—quick as the stab of a knife—that I was out of my element, trapped in alien country. You were not supposed to get scared fishing, I thought. Not supposed to go squid-soft and pale.

Lee looked at the tortured graphite, the singing line. I looked at him.

“What should I do?”

“Let him run,” said Lee. “Whenever he lets up, tighten the drag and reel like a sonofabitch.”

“He ain’t letting up. He’s a whale, Lee.”

“Whales ain’t got teeth, son.”

Whatever this fish was, it was unbelievably strong. I pictured a big stingray, shooting along the bottom like a stealth bomber, trailing that spiked whip of tail. Or something else. I thought of the yellowy Polaroids tacked up in a nearby bait shop, showing the bloody red mouths of sharks caught off the municipal pier. People said that Saint Simons Sound—the strait between here and Jekyll Island, one mile south—was the largest shark breeding ground on the east coast.

The fish streaked laterally across the horizon, pulling the line dangerously taut. Swells were rolling against my chest. I could reel only in jerks. I started staggering backward, backpedaling, dragging the fish toward shallower water. I was soft from the surgery, out of shape. The tendons of my arms burned like lit fuses. My breath was fast and hoarse, my saliva thick enough to chew. I could feel my heart in my ears, throbbing. Lee kept shouting instructions.

“I’m trying, goddammit!”

The tug-of-war continued. Five yards, ten. Fifteen. Then a long wave rose before us, rolling high and green into the sun. The line skittered up through the rising water, and there, silhouetted inside the sunshot greenhouse of the swell, was the fish I’d hooked.

“Shark!”

The silhouette was unmistakable: sharp as the point of a spear, finned like a jet fighter. Fear broke through my blood. I could feel my own kidneys dangling in the red sea of my blood. My newly-sutured foot felt small and twisted, my wasted calf glowing like a fish belly in the dark water, just asking for teeth. I’d heard of sharks attacking beachgoers in waist-deep surf.

Still, I didn’t think to cut the line. It was not courage or fear or pride. It simply didn’t occur to me, as if I’d been hooked myself—a stainless barb in my own jaw or hands or heart. I could feel every twitch and throttle of the creature through the thin white sinew of the line. I could picture him whipping through the darkness, trailing a red string of blood from his mouth.

I kept staggering backward in the surf, heaving the rod like a giant lever. I could hardly get enough air. My arms no longer burned. They felt willowy and strange, spent. But it was working. The surf crashed and foamed around our waists. Then our thighs, our knees. We were rising taller from the water, step after step. Retreating toward dry land. Supremacy.

When my heel struck the exposed sand of the bar, I dug into a crouch, straining against the line. The fish had tired, but it seemed made of pure lead or iron now, like I was hauling in an anchor. I reeled and heaved, reeled and heaved. At the height of my pull, just when my tendons seemed ready to break, the line went sudden-soft, spiraling into a long curly-cue. At the other end, a panicked splashing in the surf. Lee jumped in place, sighting over the foam.

“He’s grounded!”

We approached on our tiptoes, the tide swirling around our ankles. The shark was beached in two inches of water. He flopped weakly, near-dead from the fight. He wasn’t as big as I thought—possibly four feet long. His iron-gray fuselage gleamed in the sun. His fins carried dark points, as if dipped in ink.

“Blacktip,” said Lee.

The fish lay flat on his belly, gills flared. Asphyxiating. The hook hung from a ragged cavity of mouth flesh. The black fins flailed like undergrown wings. The eyes were buttonlike, wide. This deadly creature, which I had torn from the surf, was dying at my feet.

Guilt stabbed through my chest, sucking out my breath. I felt a sudden panic. Lee was squatting beside the fish, twisting the hook free with a pair of needle-nose pliers. Without thinking, I dropped to one knee and scooped my hands under the fish’s belly. Lee raised the freed hook like a question.

“The hell?”

Before he could stop me, I’d hefted the fish high from the beach and gone running back into the surf. I ran high-kneed, holding the fish at arm’s length, belly-up, like some offering to the sea kings. Neptune or Poseidon. Lee had told me about tonic immobility—the hypnotic state that sharks and rays entered when inverted. In the Farallon Islands, off San Francisco, killer whales were known to hold great white sharks upside down, killing them.

It didn’t work. The shark exploded to life in my hands, whipping and thrashing with astonishing violence, his teeth flashing bright. I could hardly hold him. I was hardly knee-deep in the surf when I heaved the shark from my hands like a bomb. I remember the fish whirling toward me in midair, flashing his wicked grin, but I was already wheeling in the opposite direction. I ran for my damn life, imagining those selfsame teeth snapping my Achilles tendons like rubber bands.

Back on the beach, I collapsed with dramatic effect. Lee squatted over me.

“That, boy, was probably the dumbest shit I have ever seen.”

When I got up, I saw that the tide had crept high up the bar, swirling and foaming around our tackle. Likely, it would have reached the shark in time. Likely. As for us, we now faced a mile-long hike to shore, the surf eating up the sandbar in our wake.

We gathered up our gear and started across the sand. We marched toward the afternoon sun, trailing long tails of shadow. I thought I could feel the steel staples in my foot, aching in the bone. The mouth-shaped wound in my heel, where they pulled out the steel pin, howled. But the pain was different now. A choice I had made. I could limp with pride.

Then we reached the tidal cut. The stream, ankle-deep on the hike out, had swelled with the incoming tide. It was as wide as a small river now, dark with depth. Who knew how deep. The surface was wind-riffled, sliding between the banks like the scaled skin of a snake. That fast.

I looked at Lee.

“You think we can cross okay?”

Lee looked back at the crashing line of surf, so much closer now.

“I don’t think we have a choice.”

He hefted the five-gallon bucket of tackle onto his head and stepped into the shallows.

“Wade with your feet wide,” he said. “Straddle-legged.”

I nodded, followed. The current tugged at our ankles, our calves, our knees. The tide seemed to have fingers. They curled around our legs, drawing us toward the sucking mouth of the inlet. We waded deeper, deeper, descending toward the middle of the stream.

When the water reached our waists, I started thinking about sharks again. We grew up knowing they were around, but I could feel their proximity now, as if I were still wired to that blacktip. Sharks were no longer abstractions. They were throbbing through the darkness, fierce and strong. They were here. I sensed my power sinking with every step, every inch of depth. In two feet of water, I was a king. In four feet, meat.

At midstream, the tide reached our chests. We held our gear over our heads. The current bumped and eddied at our throats, threatening to topple us. We could be sucked out into the deep black water of the inlet, drowned, or my blacktip shark could come for revenge, tearing into our bellies or underparts. Or both. The water brushed my chin.

Then we were rising again, climbing the far bank, the bottom ridged beneath us like steps. We emerged onto the soft sand of the upper beach, man-tall, breathing hard. The sunbathers were all but gone, fled from the lengthening shadows. We made for the boardwalk, the sand squeaking beneath our feet.

Soon we were standing at the Jeep, looking back at the sandbar. It was nearly gone, a spit of sand at the mouth of the inlet. An island barely escaped. The tide was moving fast like a river, flooding the place. I thought of the living weapon we had pulled from the dark country of that water, then put back.

That day, we were kings.