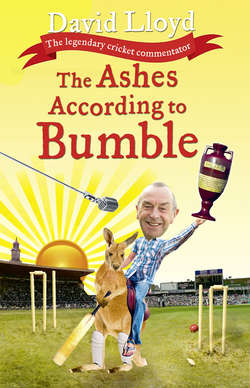

Читать книгу The Ashes According to Bumble - David Lloyd - Страница 13

Exploding the Myth

ОглавлениеDespite all of the pain inflicted, being on an Ashes tour was a great experience. The reality was that I was not good enough as an individual and neither was the team collectively, but being a part of a tour like that, travelling all over Australia on Ansett Airlines’ internal flights, getting acquainted with the Australian way of life, and the subtle differences between the cities was a real career high and a great life experience. A tour like that was long and, against superior opposition, provided no respite. I know the current players talk about the length of tours, and the stretch of time they are expected to be away from home, but what you can’t appreciate now is just how tightly the games were shoehorned into the schedule between late October and early February. Physically it was very demanding, particularly given the fact that we were still playing under the old Australian regulation of eight-ball overs.

Those eight-ball overs were an important dynamic in the flow of matches. Australia hit us hard with pace, and with a few deliveries an over sailing past your nose end, it felt as though we were being pinned down. At the start of an over, we knew that if we got through the first couple of deliveries from Lillee or Thomson there were still half-a-dozen more to come. Talk about dispiriting. On our side we only had Bob Willis with genuine speed, but his dodgy knees only allowed him one burst at full tilt. This in itself came with a caveat: if he over-stepped a couple of times he was suddenly looking at 10 balls before he got his breather, and his run-up was one of the longest the game has witnessed.

While aggression was one of the keys, if not the key component, of the captaincy of Ian Chappell – or Chappelli as he is more commonly known – the competitive edge never turned into abuse. Don’t get me wrong, the will to win was unmistakable but you sensed he wanted it to be done fairly, even against the English. As a cricketer, I found him as honest as they came, and I am not sure he would have stood for unbridled nastiness from his players. I certainly respected him, and would call him ‘captain’ or ‘skipper’ as was the common practice towards the figurehead of your opposition in those times.

In fact, he was too generous on occasion, and I might have avoided my crisis in the Balkans had the Australians bothered to appeal when, on 17, I shaped up to a Thomson delivery; the extra bounce meant the ball got too big on me, and ran up the face of my bat on its way through to wicketkeeper Rod Marsh. I immediately went to put the bat under my arm – as English players you walked in those days – only to realise there was no appeal forthcoming. I waited another split second to listen for the ‘HOWZEE?!’ and the ball being thrown up in the air. But it never came. There was nothing, other than a ‘well bowled Thommo’ and so, as I had turned 270 degrees, there was nothing for it but to let out an apologetic cough and begin some phantom pitch prodding.

This respect for Chappell, held by our team collectively, was in no small part for what he had done for Australia since they had lost the urn in 1970–71. In 1972, they had come to England and earned a draw, and now he was going up a level. He had got this team together and it gelled beautifully – you could tell they were playing for their captain too. Didn’t they flippin’ just.

Like any other team during that generation they had financial issues with their governing body; they were not too enamoured with their appearance fees, because of the insubstantial proportion of the revenue generated from the huge crowds of that series ending up in their pockets. Chappelli’s trick was arguably to spend as much time off the field batting for his men – negotiating better rates of remuneration – as he did on it.

Because once they crossed the white line, boy did those eleven men answer to his tune. They were supremely fit and a very well-balanced side. They had guys who carried out unheralded roles such as Max Walker, who, arms and legs akimbo, would run in and bowl all day. Walker possessed great stamina, a facet which allowed Chappell to rotate Lillee and Thomson at the other end. Then there was Ashley Mallett, a wonderfully steady bowler, who offered that spinner’s gold – control. Although some of the edges from the short balls flew just out of reach, the Australian slip cordon caught just about everything that you would deem a chance, and so they were always going to beat us over a six-match series.

Although we had some feisty fighters, most notably Greig and Alan Knott, there was undoubtedly only one team in it, and despite the drawn third match, Melbourne’s Boxing Day Test, going down to the wire with all three results still possible – Australia needed six runs, us two wickets – the only match we won was the last, and one of the two I missed.

Having begun the campaign late following that broken digit, I was forced back onto the sidelines and onto an early flight back to the UK, boarding it shortly after the second MCG match had got underway. The injury, a long-standing one to my neck, was aggravated taking evasive action at short-leg in a game against New South Wales, and although I subsequently played in Adelaide, my pair of single-figure scores there were to be my last in Test cricket. So as I flew back to the UK nursing two damaged vertebrae, my team-mates cashed in. Thomson was ruled out of the series finale through injury and that other menace Lillee lasted half a dozen overs before breaking down. I believe it is called the law of the sod.