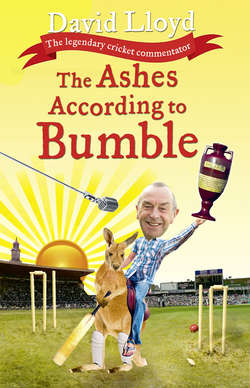

Читать книгу The Ashes According to Bumble - David Lloyd - Страница 7

Chapter 1

ОглавлениеCan there be anything in sport so small that creates such a big fuss? After all, when you break it all down, us English and those Australians have spent one and a quarter centuries skirmishing over a six-inch terracotta urn. If it’s in your possession – metaphorically speaking, of course, because it never leaves its safehouse at Lord’s – then everything is fine and dandy in the world. But if the opposition have their mucky paws on it, then start drawing up the battle plans because we want it back.

It is the primary rivalry in cricket and dates back to 1882, when England’s sorry chase of 85 to beat Australia at the Oval fell short, leaving star man WG Grace embarrassed and The Sporting Times bemoaning the death of English cricket in a mock obituary.

‘In Affectionate Remembrance of English cricket, which died at the Oval on 29 August 1882, Deeply lamented by a large circle of sorrowing friends and acquaintances – R.I.P. – N.B. The body will be cremated and the ashes taken to Australia,’ wrote Reginald Shirley Brooks. I am unsure he can have imagined what his words would lead to.

Players from both countries have made their names on the back of performances in this greatest of series, and some of the attitudes of the greatest names have recurred in subsequent generations. Grace was quite a character of course, and one who used to inform opposition bowlers: ‘They’ve come to watch me bat, not you bowl.’ Sounds familiar, does that. I am sure there is some bespectacled bloke who played for Yorkshire for donkey’s years who used to say exactly the same, who now believes folk turn on the radio rather than TV for similar reasons. I actually got him out a couple of times but the name escapes me.

Grace was a beauty. You had to uproot his stumps to get rid of him apparently, as a nick of the bails would simply result in him setting the timber up again and carrying on as if nothing had happened. No wonder he scored more than 50,000 first-class runs in his career. Sounds like it was three strikes and you’re out in his rulebook. ‘I’ll have another go, if you don’t mind. Oh, you do mind? Well, I’ll be having another go, anyway.’

Then there was the godfather of bowlers Sydney Barnes, who, plucked from the Lancashire League, used to scowl and complain if asked to bowl from the ‘wrong’ end. He had a frightful temper, it was said, and aimed it at his own team-mates as much as he did at opponents. ‘There’s only one captain of a side when I’m bowling,’ he brashly once declared. ‘Me!’

Technically, England were the first winners of the Ashes 130 years ago under the captaincy of the Hon. Ivo Bligh, who announced his intention to put Skippy on the hop upon arrival in Australia. ‘We have come to beard the kangaroo in his den – and try to recover those Ashes,’ he is said to have told an audience at an early dinner on the tour. He did just that, returning to Blighty with a commemorative urn full of ashes of some sort, which was then bequeathed to the Marylebone Cricket Club upon his death in 1927.

Bligh’s victory began a period of dominance of eight England wins on the trot, a record sequence that the Australian teams that straddled the Millennium managed to equal but not surpass. Eight series victories in a row sounds as if it would dilute the intensity, but not a bit of it because in this duel you simply cannot get bored of coming out on top.

If there is one thing I really love about England v Australia clashes it is the win-at-all-costs mentality that prevails. I’ll declare my hand here. I hate losing, always have done, always will do. Bunkum to the stiff-upper-lip brigade who believe it is all about the way the cricket is played rather than the result. For my mind, as long as you do not transgress into the territory of disrepute, as long as you behave as you would if your parents were stood at mid-on and mid-off, and as long as you are acting within the laws of the game it’s all a fair do to me. In short, play as hard as possible.

Of course, there have been times when this ship’s sailed a bit close to the wind, but the history of the Ashes is richer for its great conflicts. Growing up as a cricket fan, there were some legendary tales to take in. As series that outdate me go there are none more memorable than that of 1932–33. So memorable in fact that it took on a name of its own: Bodyline.

During its course, the Australian captain Bill Woodfull exclaimed: ‘There are two teams out there on the oval. One is playing cricket, the other is not.’

Now that Douglas Jardine, the man in charge of the team alleged to be not playing cricket, sounds like an intriguing character. One who went around treating everyone else with utter disdain. Seems he didn’t like the Australians much, and didn’t have a great deal of time for his own lot either if they were ‘players’ rather than ‘gentlemen’. England captain he may have been, but he was from the age of teams being split between the upper classes and those ditching hard labour for graft on a sporting field. But as an amateur, he had little time for those who sought to make cricket their profession.

His task was fairly simple: to stop Don Bradman’s free-flowing bat in its tracks. His mind was devoted to curbing Bradman’s almost god-given skill, and he was chastised for coming up with a solution that served his England team’s purpose. One of the phrases I like in cricket is ‘find a way’. It is after all a game of tactics and, in Jardine, an Indian-born public schoolboy, England had a master tactician who found a way to win.

I guess he was the first in a long list of uncompromising captains in what is undoubtedly the greatest rivalry in cricket. From both English and Australian perspectives it is the series that matters. The number one. Possibly the only one to some.

There is no point downplaying its appeal because here is a series that draws the biggest crowds, the largest television audiences and generates the most chat down the local. Others are simply incomparable. In political terms our historical arch enemy has been Germany. The sporting equivalent is Australia.

Sounds to me like Jardine treated the Ashes as a war. Or perhaps more accurately, he tried to turn it into one. In his mind, all Australians were ‘uneducated’ and together they made ‘an unruly mob’. He lived up to this air of superiority by wearing a Harlequins cap to bat in. I guess that was the 1930s equivalent to go-faster stripes on your boots, peacock hair, diamond earrings and half-sleeve tattoos. I am not sure Jardine needed a look-at-me fashion statement, though, to draw attention to himself.

There was something more significant in Jardine’s behaviour that put him ahead of his era, though, and that was his use of previous footage to prepare for that 1932–33 tour. He watched film of Bradman caressing the ball along the carpet to the boundary during the Australians’ 1930 tour to England, and most probably grimaced. Bradman piled up 974 runs in Australia’s 2–1 victory that summer. But, having reviewed the action, Jardine is said to have noticed something from the final Test at the Oval. Although he took evasive action, Bradman apparently looked uncomfortable at short-pitched stuff sent down by that most renowned of fast bowlers Harold Larwood. He did well to spot it amongst the flurry of fours, I guess – Bradman scored a double hundred – but he was prepared to test the theory that Bradman did not like it up him.

The planning stage took in a meeting in Piccadilly with Larwood and others in August 1932, and continued in September when the England team set off on their month-long voyage down under. You can just imagine Jardine on the deck of the ship, rubbing his hands together, scheming like a James Bond villain. The evil henchmen that would make Bodyline famous were the Nottinghamshire pair Bill Voce and Larwood, a barrel-chested left-armer and a lithe, fairly short paceman whose cricket career rescued him from the daily grind of the pit. It was said that Larwood’s work as a miner gave him the extra strength to generate extreme pace. Just as now, pace has always been the ingredient that worries top batsmen most, and the one that made the Bodyline tactic successful.

The Ashes has had a habit of bringing out the dark arts and series like that have taken on almost mythical status. It seems like another world when you read about Mr Jardine but you can’t help chuckle at his behaviour. It’s like one of those 1930s talkies at the local cinema. This bloke turns up from down pit and is met by the villainous boss. ‘Now this is what I want you to do for me, Larwood. Are you clear?’

‘Certainly, sir, no problem. I’ll knock their heads off, if that’s what you want?’

These days a short one into the ribs is a shock weapon for a fast bowler but in Jardine’s tactical notebook it was a stock delivery. They say that the potency of Bodyline was evident even in the final warm-up matches of the tour when Bradman began to lose his wicket in unusual ways. In attempting to duck one bouncer, he left the periscope up and was caught at mid-on. Another piece of evasive action had resulted in him being bowled middle-stump. Suddenly, Bradman’s batting was no longer Bradman-esque.

Uncertainty does strange things to players and the photograph of Bradman’s first ball of the series – he had missed the first Test defeat citing ill health – shows it can even infiltrate the very best. The great man is well outside off-stump as he bottom-edges a Voce long-hop to dislodge the bails and complete the very first and very last golden duck of his international career.

Australia actually levelled the series in that second match at Melbourne. But it was in the next Test at Adelaide, upon the liveliest of pitches, where it all kicked off. Big style. It was from the dressing room at the Adelaide Oval, where he was laid out recovering from a blow to his solar plexus administered by Larwood, that Woodfull’s famous assertion that England had fallen short of the necessary spirit of the game made its way into the world.

To suggest the crowd were unhappy with the bombardment sent down to a leg-side trap would be like saying Marmite polarises opinion. In an age when the crowd reaction tended to be rounds of applause and hip hip hoorays, imagine how collective chants of ‘get off you bar steward’ or words to that effect would have sounded. From some pockets of the stands came the 10 count, as used in boxing, to suggest that the bouncer assault should be stopped.

Good old Jardine thrived on the confrontation, and could not give a hoot that the locals were sufficiently roused to tear down their own ground. An England captain in Australia has to have a thick skin. Luckily, Jardine’s exterior was the human equivalent of a rhino’s hide. Even his own tour manager, Pelham Warner, was uneasy about the conduct of the tourists in setting leg-side fields and aiming for the line of the body. It boiled over, of course, when Aussie wicketkeeper Bert Oldfield was felled by a top edge into his own skull, shaping to hook a Larwood bouncer. With blood on the pitch, no wonder Larwood and Co feared being lynched by the mob.

The best players through history adapt, yet when Bradman did in this particular series, eschewing conventional technique for shuffling this way or that as the bowler hit his delivery stride, he copped criticism. There were even calls for him to be dropped. This bloke, a flippin’ genius whose career Test average of 99.94 put him as close to cricket immortality as anyone has got, finished the series as Australia’s leading run-scorer. But there were still those questioning him, and whether he had the stomach for the fight against the fast stuff. The triumph of Larwood, who claimed 33 series wickets, over the boy from Bowral was key to England’s 4–1 win.

I would suggest that Anglo-Antipodean relations were at an all-time low that winter, and the Australian board’s wire back to the MCC claiming that the bodyline bowling had challenged the best interests of the game only added gasoline to the barbie. There is nothing like the use of the term ‘unsportsmanlike’ to ignite things. Unless the practice was stopped at once, it warned, the friendliness between the two countries was under threat. The MCC response was to insist no infringement of the laws, or indeed the spirit, of the game had taken place and that if the Australian board wished to propose a new law that was a different matter.

The MCC even volunteered culling the remainder of England’s tour. But that would only have halted the best theatre Australia had to offer. Of course, when there is some niggle, when the cricket is at its most hostile or spectacular, out they come. Think of the crowds shoehorned in during 2005 and the incredible television viewing figures that went with that, or even those of the following series in Australia when Ricky Ponting’s team sought and exacted their ultimate revenge. When the entertainment is box office, up go the attendances.

Some players like to stoke themselves up by engaging in chat with opponents, not necessarily with ball in hand but with bat, and Jardine was one for seeking out pleasantries with the crowd as well as members of the fielding side. He used to bait the masses on the famous hill at Sydney by calling for the 12th man to bring him a glass of water. It was all part of the pantomime, of course.

I reckon it would have made his trip had there been WANTED posters slapped on billboards all over Australia that year. But he didn’t have to leave the pavilion of their premier cricket grounds to discover he went down about as well as gherkin and ice cream sandwiches to your average Aussie. Legend has it that after taking exception to one on-field exchange, Jardine marched into the home dressing room to remonstrate with the opposition. He claimed he had heard one of them call him a ‘pommie bastard’ under their breath. He was met at the door by Vic Richardson, Australia’s vice-captain, who is said to have addressed the rest of the room with: ‘Alright, which one of you bastards called this bastard a bastard?’ Just about the right tone, that. What goes on, on the pitch, stays on the pitch – unless the stump microphones are turned on, of course.

Bradman was the major draw card for a couple of decades of Ashes conflict, and what an anomaly he was in the history of our great game. Name any team you want, any decade you want and there is no-one to come close to what he did on the world stage. At 20 years of age he became the youngest player to score an Ashes hundred, and from that point forth he made records tumble like dominoes down a hill.

At Headingley in 1930, he scored 309 runs in a day. That must have felt like one man against 11 for that particular England team. When he took over the captaincy for the 1936–37 series, he became the first man in history to lead a team to victory having been two Tests down. With this Clark Kent-esque figure around there was not much room for others to breathe.

Len Hutton registered the highest individual Ashes score of 364 at the Oval in 1938, in England’s whopping innings-and-579-runs victory, but still Bradman’s Australia held the urn. The great Wally Hammond went on into his 40s in his bid to finally overthrow him. As Jack Hobbs said: ‘The Don was too good: he spoilt the game.’

In his final series, Bradman fronted the 1948 ‘Invincibles’ – what a team they were. Not only did they win the Ashes 4–0 that summer, they also went 34 matches undefeated on the tour, led by fearsome fast bowlers like Ray Lindwall and Keith Miller. In the 1950–51 series that followed, attendance figures were down by more than 25% on the previous one down under. Although my old mate Warnie sports the nickname ‘Hollywood’ it is fair to say that Bradman was exactly that. As soon as Australia’s A-list performer hung up his boots, folk appeared less keen to turn out. And what a way to go – bowled by a googly from Eric Hollies second ball in his final Test innings when only requiring four runs to finish with an average in three figures. No matter how you dress it up those numbers are absolutely mind-boggling.