Читать книгу A Parliament of Owls - David Tipling - Страница 18

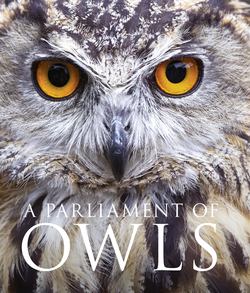

ОглавлениеA Striped Owl perches on a palm frond, revealing the prominent ear tufts typical of the Asio genus.

02 | CENTRAL & SOUTH AMERICA

FOR THE ORNITHOLOGIST, THE NEOTROPICS— that is to say, the combined continents of South and Central America— offer riches beyond those of any other continent. Although South America may be only two-thirds the size of North America, covering an area of some 6.9 million square miles (17.8 million sq km), it is home to around three times as many bird species: more than 3,200 in total. Indeed, the world’s three most bird-rich countries, in terms of number of species, are Colombia, Peru, and Brazil, in that order.

This general avian profusion is hardly surprising, given that much of the region is carpeted with tropical rain forest, the world’s most biodiverse habitat. It centers upon the Amazon Basin, the world’s largest forest, but also extends north into Central America and down the Atlantic west coast of Brazil. Within this world of green, owls play their part in the grand avian assemblage, with some fifty-five species recorded in South America and twenty-nine (including some that overlap the two) in Central America.

Many neotropical owls are relatively little known, however, compared with their relatives in the northern hemisphere. This is precisely because they occur largely in dense, remote tropical forest that does not give up its secrets easily. It is, perhaps, for the same reason that they have not generally attracted the equivalent wealth of literature, folklore, and imagery as have owls in some other parts of the world.

The prolific biodiversity supported by tropical rain forest reflects the year-round supply of rain, warmth, and sunlight, which in turn fuels ceaseless plant growth, thus creating an inexhaustible food supply and a huge variety of ecological niches. From the stratified layers of a tree canopy to the aquatic carpet of a flooded swamp forest, the forest teems with invertebrates, reptiles, birds, and small mammals, all of which offer rich pickings for a variety of owls. This constancy of weather and food supply means that, like most other rain forest birds, the owls have no need to migrate or wander far in search of prey. In addition, the cat’s cradle of the canopy, with its creepers, epiphytes, and rotten wood—riddled with the excavations of woodpeckers and other arboreal animals—leaves them spoilt for choice when it comes to places in which to roost and nest.

Typical rain forest owls include such charismatic species as the Spectacled Owl, with its unmistakable facial markings, and the Crested Owl, with its bizarre headgear. Others include a wide variety of pygmy owls, such as the Ferruginous Pygmy Owl, which take up prominent perches in forest clearings and edges, often by day, and hunt with great agility for birds and other small vertebrates. Members of the wood owl (Strix) genus are also well represented, with species such as the Black-banded Owl, which often finds a home in banana plantations and other cultivated areas in the forest, and the Mottled Owl, which calls with a characteristic frog-like hooting.

The calls of rain forest owls, although many and various, are generally heard against a rich background chorus of insects, amphibians, and other nocturnal songsters. This may partly explain why these calls have acquired a little less cultural prominence than those of species in northern climes, where the voice of an owl in a forest after dark—especially during winter—often has the added impact of being the only voice.

South America has many other landscapes beside forest. Running down the western flank of the continent, spanning some 4,300 miles (7,000 km) from top to bottom, are the Andes. This enormous mountain chain, the world’s longest, offers its own rich mosaic of habitats, from misty cloud forest to snow-capped peaks and high tundra-like páramo. Owl species that inhabit these higher elevations include the Andean Pygmy Owl (Glaucidium jardinii), the Buff-fronted Owl (Aegolius harrisii), and the endangered Long-whiskered Owlet (Xenoglaux loweryi), the last of which is a tiny species that hunts among the mosses, orchids, and epiphytes of the Peruvian cloud forest.

South America also harbors large areas of grassland, graduating from the tropical Cerrado savanna of Brazil to the more arid plains further south. These open habitats are well suited to owls of the Asio genus, which breed largely on the ground and hunt by quartering the grass on long wings for small prey below. Tropical grasslands are home to the handsome Striped Owl, which resembles the Long-eared Owl of the northern hemisphere. Further south, the Short-eared Owl, one of the world’s most widely distributed species, makes its home alongside the rheas and guanacos of the pampas. This bird, perhaps greatest wanderer in the owl family, has even colonized the Galápagos Islands, some 620 miles (1,000 km) off the coast of Ecuador, where a number of scientists now believe it has evolved into a new species, the Galápagos Short-eared Owl (Asio galapagoensis).

Some owls even find a home at the tip of the continent in the cold wastes of Tierra del Fuego. These hardy species include the Rufous-legged Owl (Strix rufipes), which occasionally makes its way across to the Falkland Islands from Argentina, and the Magellanic Horned Owl (Bubo magellanicus), a southern relative of the very similar Great Horned Owl, found across much of the Americas. The latter is a generalist, making itself at home in a variety of habitats, from pampas to farmland and the coastal dunes of Patagonia.

Sadly, the birds of the world’s most bird-rich continent are far from secure. Vast swathes of tropical forest have been lost to logging, mining, and slash-and-burn agriculture, and today more than 300 species face extinction. Owls are no exception, and those species that continue to do well tend to be the ones that have adapted to cultivation and human settlement.

A family of Tropical Screech Owls regard the photographer with collective curiosity.

The impressive talons of the Ferruginous Pygmy Owl provide more power than its diminutive size might suggest.

Typical habitat for the Spectacled Owl is the tangled mid-story of lowland tropical rain forest.

SPECTACLED OWL

PULSATRIX PERSPICILLATA

APPEARANCE

Medium-large, with rounded head and no ear tufts; upper parts plain chocolate-brown to black; under parts pale yellowish to fawn, with broad brown breast band; black head with white throat band; black facial disk boldly marked with white eyebrows and lores that create spectacles effect around bright yellow eyes.

SIZE

length 16 – 20.6 in. (41 – 52.3 cm)

weight 1 – 2.76 lb (460 – 1,075 g)

wingspan 49 – 59 in. (125 – 150 cm)

DISTRIBUTION

From southern Mexico south through Central America and across the northern two-thirds of South America, south to northern Argentina.

STATUS

Least Concern

THE SCIENTIFIC SPECIES NAME OF THIS BIRD—perspicillata—translates as “sharp-sighted,” which rather suggests that it has no need to wear spectacles. Nonetheless, there is no denying that the bold white markings around its large yellow eyes recall a pair of glasses perched on its sharply hooked bill.

The Spectacled Owl is the largest truly tropical owl of the Americas, and one of the most recognizable owls anywhere. It does not have the cryptic camouflage patterning common to most of the owls described in this book: the upper parts are a plain chocolate-brown to black, while the under parts, below the dark brown breast band, are pale yellowish to fawn. However, it is the bird’s face that grabs the attention: bold white eyebrows and lores almost completely encircle the bright yellow eyes, as though the bird has pressed a pair of binoculars to its face with the eye-pieces covered in chalk. A broad white band runs across the throat and beneath the bill like a chinstrap: against the otherwise sooty black face and head, the effect is very striking.