Читать книгу A Parliament of Owls - David Tipling - Страница 7

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеOWL ENCOUNTERS ARE ALWAYS SPECIAL. My most memorable came while camping on a remote island in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. After whiling away the midday heat by stick-scribbling in the sand some of the wildlife I hoped to see—a hippo, a giraffe, and a big-eyed bird—my guide, a fisherman who spoke little English but who had clearly been paying attention, beckoned me to follow him. We tramped through a shallow lagoon to a tangle of forest, where he stopped and pointed up into a towering sycamore fig tree. It took me two minutes with binoculars before I spotted what his sharper eyes had seen immediately: a huge, ginger-orange owl staring from its roost, its inky-black eyes wide in suspicion. It was my first Pel’s Fishing Owl, the African birder’s holy grail.

Owl encounters need not be deep in the African bush. My childhood in the United Kingdom was littered with memorable moments: hearing the shrill hoot and “kiwick” of duetting Tawny Owls, a bird I had hitherto encountered only in books, outside my bedroom window; and watching Short-eared Owls quartering a winter marsh, then finding their pellets beneath a fence post and carefully extracting four perfect vole skulls. Something about these enigmatic birds commands attention and fires the imagination, which is why owls have loomed large in human culture across the ages.

That “something” is not hard to break down. First, owls are largely nocturnal and so carry all the mystery of creatures that move unseen in darkness, betrayed only by their unearthly calls. Second, when owls make themselves visible, their large, forward-facing eyes give them more of a “face” than other birds: a face upon which we cannot resist bestowing such human qualities as anger, surprise, and wisdom. And third, perhaps, are their hunting skills, deployed in pitch darkness with such stealth and perception that it fills observers with awe. In some places, awe has become fear. Traditional cultures have long associated owls with sinister forces. Similar myths recur, from African villages to Mediterranean olive groves: typically, that an owl’s presence, or even just its call, near a human dwelling foretells a death in the family or some such disaster. Elsewhere, though, owls have come to embody more positive qualities, including wisdom and prosperity. This association runs from the ancient Greek reverence for the Little Owl as companion of the goddess Athene to the role of owls in such literary classics as Edward Lear’s The Owl and the Pussycat and J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter novels.

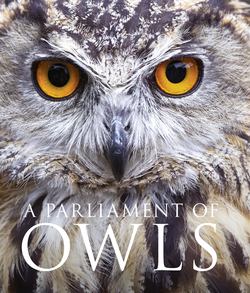

Today, the allure of the owl is also reflected in the work of many wildlife photographers who are drawn to this challenging subject. It is an allure celebrated here in David Tipling’s stunning images, and those of the other photographers he has assembled. Famously, it is a calling that also led to the loss of an eye for pioneering British photographer Eric Hosking, attacked by a female Tawny Owl whose nest site he was trying to photograph. Owls may be beautiful, but you underestimate them at your peril.

Owls in order

An owl—to allay the fears of the superstitious—is simply a bird. However, it is a bird uniquely adapted to the challenges of a predatory and mostly nocturnal lifestyle. In scientific terms, owls make up the Strigiformes, one of twenty-eight orders of bird. Although equipped with piercing talons and hooked bills, they are unrelated to diurnal birds of prey, such as eagles and hawks, which belong to the Falconiformes, an entirely separate order. The fossil record suggests that owls first appeared some 65 to 56 million years ago, and are among the oldest known groups of non-Galloanserae land birds (the Galloanserae are the game birds and wildfowl that emerged even earlier). Many species have since come and gone: one barn owl from the Pleistocene stood 3 feet (1 m) tall and may have weighed twice as much as today’s largest eagle owls.

Today’s owls fall into two families: the barn owls (Tytonidae) and the typical owls (Strigidae). Between them, these comprise some twenty-six genera and up to 250 species. The taxonomy has undergone extensive revision since the advent of DNA sequencing, producing new genera and prompting the movement of numerous species between existing genera. For example, the African fishing and Asian fish owls, each once assigned its own separate genus, are today grouped with eagle owls in Bubo. Conversely, the New World screech owls, once classified alongside Old World scops owls in Otus, now have their own genus, Megascops. Molecular studies and improved analyses of vocalizations have also brought to light the existence of many new species and have led scientists to elevate to full species status many owls that were previously thought to be geographical variations (subspecies) of existing species. The whole business of taxonomy is complex and contentious, and it remains a work in progress. This book reflects the taxonomy that is accepted by most authorities at the time of going to print, but new owl species are added to the list as research continues.

Owls depicted as cultural icons in a Punch cartoon from 1888, an Ancient Greek coin, and a clay plaque from Iraq, c. 1792–1750 BCE.

Taxonomy aside, you need not be a scientist to appreciate the extraordinary variety among owls. They range in size from the bijou Elf Owl, which at 1.4 ounces (40 g) is no larger than a sparrow, to the formidable Eurasian Eagle Owl, which, at a top weight of 10.1 pounds (4.6 kg), is big enough to kill a young deer. Owls occur on every continent except Antarctica, with 68 percent of species found in the southern hemisphere. The majority are forest birds, adapted to hunting among trees, which also provide them with nest sites and roosts. However, owls also thrive in savannas, deserts, and even the Arctic tundra, each with its own particular survival adaptations. Some species have evolved to live alongside humans, in agricultural and even urban landscapes; the Barn Owl gets its name for a reason.

Owls up close

It is easy to recognize an owl. Although individual species may be hard to tell apart, the big head, round face, and forward-facing eyes make all owls instantly recognizable as such and immediately distinguish them from other birds. In order to appreciate just how unusual these predators are, however, you need to take a closer look.

An owl’s distinctive face holds several clues to its unusual way of life. The eyes are proportionally among the largest of any animal—up to 2.2 times the size of those of similar-size birds—and, in the largest species, larger even than our own eyes. They are more tubular than spherical, thereby allowing the maximum area for the retina, which is packed with the rods that allow the acute low-light sensitivity required to operate in near-darkness (although owls do not have high-resolution color vision). Forward-facing, like human eyes, these eyes also provide the binocular vision essential for depth perception when targeting prey. You will often see an owl bob and weave its head, in order to improve this focus. However, you will not see it turn its eyes, as they are locked into their sockets by sclerotic rings of bone. Instead, therefore, owls have evolved the celebrated ability to turn their heads by up to 270 degrees in order to view objects around and behind them.

A Barn Owl hunting over a cattle pasture proves that owls can thrive in human landscapes, if suitably managed.

Perhaps even more impressive than an owl’s eyesight is its hearing. This is powered by unique adaptations, of which the most obvious is the facial disk: the circular arrangement of feathers, bordered by a raised rim, which forms a concave saucer around each eye and gives an owl its distinctive face. The facial disk works like a satellite dish, capturing sound and directing it to the ears. These are not the feathered tufts on top of the head, however, but large vertical openings at either side of the facial disk, hidden from view by feathers. Not only are they proportionally the largest ear openings of any bird, with an exceptionally large inner ear, but they are also—unusually among vertebrates—positioned asymmetrically, with one higher than the other. This produces a time lag in the auditory signals reaching an owl in both the vertical and the horizontal plane, thus giving the bird an exceptional ability to pinpoint the direction of a sound. The hearing of a Barn Owl is at least ten times more powerful than our own, and laboratory experiments have proven that it can locate and strike prey in pitch darkness by sound alone.

Contrary to popular belief, owls do not use echolocation, the technique employed by bats to navigate in darkness by bouncing sounds off their surroundings. Owls have no need with such astonishing hearing. A Great Grey Owl perched on top of a tree can hear the movement of an invisible vole beneath a layer of snow, 30 feet (10 m) below, and swoop down to it, through the snow, with unerring precision.

An owl’s hunting weaponry is similar to that of a diurnal raptor. The beak is longer than it appears, concealed behind a spray of fine feathers. Its sharply hooked tip serves both to kill prey with a bite and to tear it into pieces. It is set a little below eye level, and tilted downward to avoid impeding the binocular vision. The talons have long, needle-sharp claws, which seize, crush, and kill prey, and also provide a vice-like grip while the bill gets to work. Larger owls have frighteningly powerful feet: the talons of a Great Horned Owl may exert a pressure that is around the same as the bite of a Rottweiler and at least eight times stronger than a human hand. Owls’ toes have a zygodactyl arrangement, with two facing forward and two facing back, unlike most other birds, which have three forward and one back. Some owls’ feet have specific adaptations: the toes of fishing owls, for example, are lined with sharp scales called spicules, which help to grip their slippery prey.

This hardware is protected by feathers, and an owl’s plumage is remarkable for various reasons. Most species sport cryptic camouflage markings, with a complex tapestry of spots, bars, streaks, and vermiculations in various tones of brown, gray, ocher, and cream that serve both to replicate the birds’ background—typically a roosting spot against fissured, lichen-covered bark in dappled forest light—and to obliterate any impression of form. The ear tufts of many species, which can be lowered or erected as required, are thought to enhance this camouflage by increasing the “broken stump” appearance. It has been suggested that they make the owl’s outline appear more like that of a potentially dangerous mammal, such as a marten, and may also help to express mood. Some owl species come in different color morphs, typically brown, gray, and rufous, which tend to reflect geography, the gray morphs occurring further north. Alongside this camouflage, owls also have markings that are designed to be seen. Bold white eyebrows and black eye-rings make the facial expression all the more intimidating, while a white throat puffed out while calling may help attract a mate and deter a rival. Some species in the Glaucidium genus of pygmy owls even have false eye-markings on their nape, creating an occipital face that may give a potential predator pause for thought.

An owl’s plumage also has some very practical adaptations. Many species have tarsi (lower legs) feathered down to the toes, which protects them both from the bites of their prey and from the extremes of the cold climate in which they hunt. Fine hair-like feathers around the bill, called filoplumes, provide extra tactile sensitivity in tackling prey. In addition, and uniquely among birds, the flight feathers of most owls have special sound-proofing modifications—fine feather filaments that dampen onrushing air and a downy surface layer that absorbs high-frequency sound—that enable them, like silent assassins, to approach prey noiselessly. The wings of many species are long and broad, giving them the low-wing loading (body weight to wing area ratio) necessary to stay airborne while slowly quartering the ground for prey.

A Snowy Owl coughs up a pellet containing the indigestible parts of its prey.

How owls live

Owls, famously, fly by night, although not exclusively and not all of them. Some 69 percent of species are primarily nocturnal. Many others are more crepuscular, hunting by dusk and dawn, while 3 percent are properly diurnal. By day, most hide away in a roost, usually individually or in pairs, but a few species, such as the Long-eared Owl, form small colonies outside the breeding season. Most owls are also sedentary, remaining more or less in the same place all their life. A few northern species are nomadic, however, making irregular seasonal movements if the weather turns against them or if their prey disappears, and a few are full migrants, including the Common Scops Owl, which migrates every year between southern Europe and central Africa.

Most owls hunt either by swooping down from a perch upon unsuspecting prey or by flying slowly over open ground and dropping upon anything that their sharp hearing and eyesight detect. There are numerous other techniques: some species use agile flight to capture moths, bats, and even birds in flight; others pluck insects and frogs from the forest foliage or pull earthworms from the ground. Fishing owls are especially adapted for their task, watching for the ripples of their slippery prey, then pouncing into the shallows to grab it; these owls have bare legs, to prevent water-logging, and no full facial disk, as they do not need hearing to make a catch.

The variety of prey taken across the owl group is extraordinary, ranging from flying ants to mammals as big as foxes and birds as large as eagles. Many species take prey larger than themselves, with the smallest owls punching well above their weight when targeting birds such as doves. The availability or otherwise of certain prey species can be critical to owls’ fortunes, none more so than voles, which in northern regions provide the staple diet for species such as the Short-eared Owl. In vole “boom” years, owl populations may soar; conversely, in “bust” years, they may crash, with the owls failing to breed or moving away en masse in search of food.

A fledgling Ural Owl still in its downy juvenile plumage.

Among the more surprising items on the owl menu are other owls, with species such as the Tawny Owl and Eurasian Eagle Owl frequently preying upon smaller relatives, such as the Long-eared Owl. The practice of one predatory bird feeding upon its cousins is known as intraguild predation, and certain owls—notably the Eurasian Eagle Owl, again—are notorious in this respect, often taking hawks, buzzards, and other diurnal raptors from their nighttime roosts. Owls tend to swallow smaller prey in a single gulp, while larger prey is dismembered using the bill and talons. Either way, they cough up the indigestible parts—bones, fur, feathers, insect heads and wing cases—in a sausage-shape pellet, which takes about six hours to form. Regular owl roosts and nest sites are often betrayed by the piles of pellets that accumulate beneath. They can prove very useful to scientists, both identifying the species and shedding light on its prey and feeding habits.

Being nocturnal, many owls are more often heard than seen. The best-known calls are the hoots of the eagle owl (Bubo) and wood owl (Strix) genera, notably the Tawny Owl, whose fabled “too-whit to-whoo” has become the universal voice of spooky graveyard thrillers. However, many owls do not hoot at all. Other sounds vary from the hissing screams of barn owls to the insect-like chirruping of scops owls, the metronomic whistles of pygmy owls and the dog-like yapping of the aptly named Barking Owl. Calls are unique to each species and, for the scientist and birdwatcher, they provide diagnostic clues to an owl’s identity.

Owls are unusual among birds in that most do not visibly open their bills when calling but rather inflate their throats, like a frog. They are most vocal at the start of the breeding season, as males reclaim their territories and attract females. Most species are monogamous, and many form lifelong pairs, retaining the same territory and nest sites for numerous years. In addition to calls, pairs consolidate their bonds with mutual preening, gifts of food from male to female, and choreographed courtship rituals, including wing-clapping display flights.

Males show their mates around potential nest sites, but females generally make the choice. Most nest in tree holes, especially those excavated by woodpeckers, but some use crevices among rocks and tree roots. Many will also reappropriate the old stick nest of another bird, such as a crow or raptor, and a few even nest in a crude hollow on the ground, trampled into the long grass. None constructs a nest, and few provide any kind of lining. Owls’ eggs are generally white and quite spherical in shape, with the clutch size ranging from one or two in many species to an amazing dozen or more, during peak years, for those whose breeding is tied to the abundance of prey such as voles. The female generally incubates the clutch, while the male hunts to provide for her. Once the hatchlings have grown strong enough, both parents hunt together in order to provision their voracious brood. Although owls may be poor nest builders, they are excellent nest defenders, and species such as the Tawny Owl and Ural Owl are notorious for the attacks they launch on intruders. Other tactics are deployed, including puffing up the feathers to exaggerate their size, and feigning injury to distract an approaching predator away from the vulnerable chicks.

The youngsters grow quickly and generally leave the nest before they are fully fledged, hanging around for a while in a downy mesoptile stage before they perfect their flying and start to hunt for themselves. The young of some larger owls may remain with their parents for several months, sometimes long enough to prevent the parents from breeding the following year. In many species, especially those found in colder northern regions, breeding success is dictated by weather and food supply, and in poor years they may not attempt to breed. Once an owl gets through its tricky early years, many species go on to live long lives. Longevity records among captive owls have topped fifty years for both the Eurasian Eagle Owl and the Great Horned Owl.

Owls and people

Owls have played a significant part in human culture since before recorded history, their all-seeing eyes inspiring both fear and reverence, and prompting their symbolic depiction as, variously, harbingers of doom and emblems of wisdom and prosperity. They appear in French cave paintings dating back 15,000 to 20,000 years and in the hieroglyphics of the ancient Egyptians. In the United Kingdom, the spectral appearance and eerie call of the Barn Owl has led to numerous ghost stories, while in Jamaica the presence of a Jamaican Owl outside a house has occupants reciting an incantation to avert disaster. In Japan, conversely, Blakiston’s Fish Owl is revered by the Ainu people as “The God that Protects the Village.”

Whatever we think of owls, humans have given them plenty to contend with. In some parts of the world, owls have suffered direct persecution, either killed to ward off evil spirits or hunted for the pot. More serious, however, is the damage done to their environments. Deforestation, commercial agriculture, and river pollution have robbed owls of the habitats they need for breeding and hunting, while the use of rodenticides and other toxins have not only depleted the owls’ prey but often caused secondary poisoning to the birds themselves. Modern hazards also include man-made obstacles such as power lines and road traffic. Today, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature lists six owl species as Critically Endangered, twenty-six as Endangered, and another forty-three as Vulnerable or Near Threatened. As indicator species of a healthy environment, it is therefore the disappearance of owls, rather than their presence, that we should fear as a harbinger of doom.

Conservationists are doing their bit. BirdLife International and its partners are working hard to protect owls, whether through increased protection for their habitats or lobbying and education to prevent their persecution. More enlightened landowners, realizing that owls themselves are the farmer’s best natural rodenticide, are managing land for owls, setting aside rough pasture and other key habitat features they require, and providing nest boxes. Meanwhile, owls continue to bring great pleasure to numerous people, from fanatical “owlaholics” who devote their lives to collecting anything that depicts the birds, to hardened “world listers,” who race around the globe trying to tick off as many of its owl species as they can manage. Furthermore, there are those of us who simply love the wild, for whom that haunting voice in the darkness or unexpected flare of silent wings over a moonlit hedgerow represents all that is magical about these most enigmatic of birds.

BIOGEOGRAPHIC REGIONS (ECOZONES)

This map shows the world’s principal biogeographic regions as reflected in chapters one to five of this book. Chapter Six (Oceanic Islands) comprises parts of several other regions.

A note about the selection of owls

This book is a photographic celebration of the world’s owls, and the fifty-three species accounts describe the appearance, distribution, behavior, and something of the cultural associations of each owl. The selection aims to offer a broad picture of owls as a group, with the representatives drawn from most key genera, and covering all continents and all habitats in which they are found. However, it is impossible to strike a perfectly representative balance: the best-known owls—to science and recorded culture—tend to be found in the northern hemisphere, especially in Europe and North America. Northern parts of the world are therefore better represented than some tropical regions, which may have a greater diversity of owls, but offer less information with which to tell their story. The final chapter bucks the trend in that it is not a single biogeographical area. Instead, it comprises a particular suite of shared environmental conditions and challenges to which the owls that live on Oceanic islands, from the Caribbean to the South Pacific, have evolved and adapted in similar ways.

A hovering Barn Owl trains all its senses on prey below.