Читать книгу The Idiot Gods - David Zindell, David Zindell - Страница 11

4

ОглавлениеFor three days of wind and storm, I ranged about the channel hunting salmon to my belly’s contentment. I came across many boats. Most of these, while moving across the greenish surface of the bay, emitted a nearly deafening buzz from their underbellies, near their rear. How could these human things make such an obnoxious noise? An impulse drove me toward one of the boat’s vibrating parts, obscured by churning water and clouds of silvery bubbles. I wanted to press my face against this organ of sound as I might touch my mouth to the swim bladder of a toadfish to determine how it could be so loud. A second impulse, however, held me back. In a revulsion of ambivalence that was to flavor my interactions with the humans, I realized that I did not want to get too near the boat, which was made of excrescence as were so many of the things associated with the humans.

At other times, however, my curiosity carried me very close to these strange, two-legged beings. On a day of gentle swells, when the sky had cleared to a pale blue, I came upon a boat whose humans busied themselves with using strands of excrescence to pull salmon out of the sea. What a clever hunting technique! I thought. I swam in close to the boat to investigate.

One of the humans sighted me, and barked out what seemed to be the human danger cry: ‘Orca! Orca! Orca!’

How could I show them that I posed them no threat? Perhaps if I snatched a salmon from the excrescence strands and presented it to them, they would perceive my good intentions. I swam through the rippling water.

‘That damned blackfish is after our catch!’ A hairy-faced human called out.

His top half nearly doubled over the lower in that disturbingly human way of exercising their strangely-jointed bodies. When he straightened up, he clasped some sort of wooden and metallic stick in his hands.

‘What are you doing?’ his pink-faced companion called out.

‘Just shooting at that damned blackfish!’

‘I can see that – but what are you doing? Do you want to go to prison for killing a whale?’

‘Who would know? Anyway, I’m just going to have a little target practice to scare him off.’

‘Put your goddamned gun away!’

‘Don’t worry, I’m not going to kill him – unless he tries to take our salmon.’

A great noise cracked out; just beside me, the water opened with a small hole which almost immediately closed.

‘How did you do that?’ I shouted as I moved in toward the boat.

Again the stick made its hideous noise, and again the water jumped in response.

‘Once more!’ I said, taking a great liking to this game. ‘Make the water dance once more!’

I swam in even closer, and the holes touched the water scarcely a tongue’s lick from my face. What beguiling powers these humans had! Orcas can stun a fish with a zang of sonar, and the deep gods – who have the Great Voice, the voice of death – kill swarms of squid in this manner. No whale, however, can speak and make the very waters part.

‘If you shoot that orca,’ the pink-face called out, ‘I’m going to shoot you!’

The human holding the wood and metal stick lowered it, and the water moved no more.

‘Please, please!’ I said. ‘Let us play!’

If the humans, though, could not understand the simple word for water, how could they comprehend my more complex request? To show my gratitude that they had possessed the wit to play at all, I caught a salmon and swam right up to the edge of the boat.

‘I think he wants us to have it!’ the pink-faced human said. ‘He’s giving us his fish!’

I pushed up out of the water, with the salmon still thrashing between my teeth. Hands reached out to grasp it and take it from me. Then I dove and caught another salmon for the humans, and another. They seemed to like this game.

During the days that followed, I ranged the channel and played games with other humans. Some were as trifling as balancing pieces of driftwood on my face, while others demanded planning and coordination. The humans seemed titillated when I rose up from the deeps near their boats and flew unannounced high into the air. Many times, I surprised their littlest boats, propelled across the channel by lone humans pushing sticks through the water. It was great sport to leap over both boat and human in the same way that Kajam had once leaped over Alnitak’s back.

In the course of nearly all these encounters, the humans involved made various vocalizations, for they proved to be among the noisiest of animals. Their voices seemed to reach out to me with a terrible longing, as if the humans hoped to find in me some ineffable thing they could not appreciate within themselves. I sucked up every sound they made and examined their incessant barking and crooning for pattern and possible meaning:

‘Hey, look it’s Bobo! You can tell it’s him by the scar over his eye.’

‘I hear he likes to play.’

‘What a joyful spirit!’

‘He’s the spirit of my grandfather who has come to tell us something.’

‘I heard that some fisherman took shots at him.’

‘He was brought here for some purpose.’

‘Look in his eyes – there’s more there than in most people.’

‘Why is Bobo all alone? What happened to the rest of his pod?’

‘I think he’s lonely.’

‘When he looks at me that way, I can feel my soul dancing.’

As the days shortened toward another winter of cloud and storm, I felt a growing urge to understand the mystery of the humans. Buried inside me, like a pearl in an oyster, I felt a hard realization pressing against my softer tissues of doubt. More and more, I wanted to draw out the pearl and hold it up sparkling in the sun.

I wondered what might explain what I experienced in my forays up and down the channel. I assumed that the humans really did have a keen intelligence, though of a different and lesser quality than that of whales. They must have some sort of language, too, for how else could they organize so many complex activities? During quiet moments when the cold ocean stilled to a vast blue clarity, I could see the intelligence lighting up the humans’ eyes just as I could feel their desire to communicate with me. Do not the Old Ones say that the eyes sing with the sound of the soul?

My ancestors also tell of the forming of all things in the eternal creation of the world. From out of the oneness of water and its accompanying sound comes love, which can never be wholly distinct from its source. From out of love, in turn, emanate the sacred triadic harmonies of goodness, beauty, and truth. How could one ever marvel ecstatic at the beauty of the rising of the Thallow constellation over the starlit sea without the goodness of the heart to let in the tinkling luminosity? How know goodness absent the truth that all the horrors of life find validation in the love of life that all creatures embrace? The journey to the deepest of love, my grandmother once told me, must always lead through truth, beauty, and goodness. And of these, the waters of truth are much the hardest to navigate.

‘Only through quenging into utter honesty with ourselves,’ she had said, ‘can we hope to become more fully and consciously ourselves. Is this not what the world wants of us? If not, why did the sea separate itself into individual peals of life in the first place? That is why we must always tell the truth. For if we do not, the great song that we make of ourselves will ring false. But, Arjuna, who has the courage to really listen to the cry of one’s heart and to embrace the totality of one’s own being? Who can even behold it?’

It is a truth universally acknowledged among my kind that one can never hear completely the truth of one’s own soul. We cannot make out the ridges and troughs that form the seascapes of our deepest selves, any more than we can zang through miles of dark, turbid waters to study the bottom of the ocean. Then, too, the eye can never see itself, just as I could not look directly at the scar marking my forehead. Worst of all, we avoid doing so with a will toward the expunging of our best senses. As seals seek dark and narrow coves in which to flee the teeth of the orcas, we hide from our truest selves for we do not want to be devoured by the most primeval of all our passions.

‘What does any whale really want?’ my grandmother had asked. ‘Were we not born to be the mightiest of hunters? Do we not, in the end, pursue greater life in ourselves that we might know the infinitely vaster life of the world around us?’

We do, we do – of course we do! And yet in this glorious becoming of our greater selves, as streamlined and lovely as the orcas of Agathange, we must leave behind our lesser selves. This realization of the best and truest within us, though it yields eternal life, always feels like death. One thing only emboldens us to make the journey through life’s terrors and agonies to the end of time and the beginning of the world.

How, though, was I to achieve this greatest of purposes absent my family’s devotion and encouragement? How, without my mother, Alnitak, Mira, and everyone else, would I come by the pellucid honesty through which I would find my way through the great ocean of truth?

Although I had no answers to these questions, I knew what my grandmother would say: I must begin with the truth that I had grasped but which I was reluctant to really sink my teeth into. After playing many games with the humans, I not only hypothesized that they were intelligent, I zanged it in my heart. Why, though, had I not listened to what I had zanged so deeply?

I thought I knew the reason, and it had to do with an essential paradox: that only through looking out at all the manifold forms and features of the world can we ever apprehend the much stranger phenomena of ourselves. Just as we can see stars only against the blackness of the nighttime sky, so we need others to show us the many ways that we shine as unique sparks of creation. The greater the contrast in this relationship, the deeper the understanding.

For instance, were not females, such as lovely Mother Agena, a part of the great unknown? No other work of nature was more like a male orca such as I, and yet so utterly different. How should I then long to find myself within the wild, wet clutch of her body and even the wilder ocean of her soul? Would it not be, I wondered, that precisely in closing the difference between us and daring to enter the most dangerous place in the universe I would discover an exalted and ecstatic Arjuna whom I might otherwise not ever know?

So it was with the humans. To a whale such as I, their kind beckoned as the Great Other in whom I might discover secrets about myself that I had never suspected. Although it seemed absurd that the humans’ intelligence could in any way illuminate my own, I came to realize that I had been hiding from the truth that the humans had something precious to give me.

‘O Arjuna, Arjuna!’ I cried out, ‘that is why you have not wanted to believe what you have zanged so clearly!’

Even as I said these words, however, I knew that I was still evading myself, for I had carried through the waters a deeper reason for denying the humans’ obvious intelligence. To admit to myself that humans might have minds anything like those of whales would impel me to want to touch those minds – to need to touch them. How could I allow myself to be so weak? How could I bear the terrible truth that I was desperately, desperately lonely?

I had to bear it. I had to accept it, for my grandmother had also said this to me: ‘If you bring forth what is inside you, what you bring forth will save you. If you do not bring forth what is inside you, what you do not bring forth will destroy you.’

After that, I renewed my efforts to speak with the two-leggeds and enter their psyches. One day, when the clear cerulean sky almost perfectly matched the blueness of the sea, I came upon the boat carrying the humans I had first met in the bay. They waved their arms and whistled and called out their warning cry, which seemed completely absent of warning or apprehension:

‘Orca! Orca! Orca!’

‘Look, it’s Bobo! He’s come back to us!’

I swam up to their bobbing boat and said hello.

‘Lil’ Bobo,’ the longer of the two males said. ‘We’re sorry we scared you off last time. I guess you don’t like acid rap.’

The shorter of the males, who had blue eyes and golden hair like that of the female surfer who stood next to him, drank from a metallic shell and let out a belch. He said, ‘Who does like it? Why don’t we try something else?’

‘What about Radiohead?’ the longer male said.

The female surfer used her writhing fingers to pull back her golden hair. She lay belly-flat on the front of the boat, and dipped her hand into the water to stroke my head.

‘Let’s play him some classical music.’

‘I don’t have anything like that,’ the golden-haired male said. I guessed he must be the surfer’s brother.

‘I downloaded a bunch of classical a few weeks ago,’ the surfer said, ‘just in case.’

‘Like what?’

‘I don’t know – I don’t really know anything about classical.’

‘Let me see,’ the longer male said.

He bent over, and when he straightened, he held in his hand a shiny metallic thing, like half of an abalone shell.

‘What about the Rite of Spring?’ he said. ‘That sounds like some nice, soft music.’

A few moments later, from another shiny object that seemed all stark planes and hard surfaces like so many human things, a beguiling call filled the air. In its high notes, I heard a deep mystery and the promise of life’s power, almost as if a whale were keening out a long-held desire to love and mate. Soon came crashing chords and complicated rhythms, which felt like a dozen kinds of fish thrashing inside my belly. Various themes, as jagged as a shark’s teeth, tore into one another, interacted for a moment, and then gave birth to new expressions which incorporated the old. Brooding harmonies collided, moved apart, and then invited in a higher order of chaos. Such a brutal beauty! So much blood, exaltation, splendor! The human-made sounds touched the air with a magnificent dissonance and pressed deep into the water in adoration of the earth.

‘What kind of crap is that?’ the golden-haired male said. ‘Turn off that noise before you drive Bobo away again!’

O music! The humans had music: strange, powerful, and complex!

And then, as suddenly as it had begun, the music died.

‘No, no!’ I cried out. ‘More, please – I want to hear more!’

The longer male’s fingers stroked the abalone-like thing for a few moments. He said, ‘What about Beethoven?’

A new music sounded. So very different from the first it was, and yet so alike, for within its simpler melodies and purer beauty dwelled an immense affirmation of life. As the sun moved higher in the sky and the surfer female on the boat stroked my skin, I listened and drank in this lovely music for a long, long time.

Finally, near the end of the composition, a great choir of human voices picked up a heart-opening melody. I listened, stunned. It was almost as if the Old Ones were calling to me.

O the stars! O the sea! They sang of joy!

This realization confirmed all that I had suspected to be true. Although the ability to compose complex music could not be equated with the speaking of language itself, does not all language begin in the impulse of the very ocean to sing?

‘All right, so he likes Beethoven. Let’s try Bach and Brahms.’

As the sun reached its zenith in the blue eggshell of the sky and began its descent into its birth place in the sea, the humans regaled me with other musics. I listened and listened, lost in a sweet, sonic rapture.

‘I think he loves Mozart,’ the shorter male said.

‘I think he loves me,’ the golden-haired surfer said. ‘And I love him.’

To the murmurs of a new melody, the female leaned far out over the boat and pressed her mouth against the skin over my mouth.

‘Bobo, Bobo, Bobo – I wish I could talk to you!’ she said.

‘I wish I could talk to you,’ I told her. I wished I could understand anything of what she or any human said. ‘Can you not even say water?’

I slapped the surface of the sea with my flukes, and carefully enunciated, ‘Water. W-a-t-e-r.’

‘It’s like he wants to talk to me,’ she said.

Having grown frustrated in my desire to touch her with the most fundamental of utterances, I drank in a mouthful of water and sprayed it over her face.

‘Oh, my God! You soaked me! How would you like it if I did that to you?’

Again, I sprayed her and said, ‘Water.’ And then she dipped her hand into the bay, brought it up to her mouth, and sprayed me.

‘So you like playing with water don’t you?’ she said. ‘Well, you’re a whale, so why shouldn’t you? Water, water, everywhere you go.’

Her hand, her hideous but lovely hand that had sent waves of pleasure rippling along my skin, slapped the water much as I had done with my tail. And with each slap, she made a sound with her mouth, which had touched my mouth: ‘Water, water, water.’

The great discoveries in life often come in a moment’s burst like the thunderbolt that flashes out of a long-building storm. I listened as the golden-haired surfer said to me, ‘I wish I could teach you to say water.’ And all the while her clever hand touched the sea in perfect coordination with the sound that poured from her mouth: ‘Water, water, water.’ I realized all at once that she was trying to teach me to speak, in the human way. I realized something else, something astonishing that would open the secret to communicating with these strange animals:

One set of sounds, one word! The humans do not inflect their words according to circumstance, context, or the art of variation! Not even our babies speak so primitively!

‘Water,’ the surfer said again. ‘You understand that, don’t you, Bobo?’

Water, water, water – she kept repeating the simple sequence of taps and tones with an excruciating sameness. I tried to return the favor, trilling out one of the myriad expressions for water in a single way: water.

‘I don’t understand you, though,’ she said to me. ‘I don’t think human beings will ever be able to speak whale.’

The brightness in the surfer’s blue eyes faded, as when a cloud passes over the moon. I feared that she did not understand me.

‘No one can speak to a whale,’ the longer of the males said. ‘They probably don’t even have real language.’

The surfer female looked at me. She thumped her hand against the smooth excrescence upon which she lay and said, ‘Boat.’ And so I learned another word. This game went on until dusk. I collected human words as a magpie gathers up colorful bits of driftglass: Shirt. Fork. Beer. Hair. Ice. Teeth. Lips.

Finally, as the sun sank down into the crimson and pink clouds along the western horizon, the female pressed her hand over her heart and said, ‘Kelly,’ which I supposed must be what the humans call their own kind. The longer of the two male kellies made a similar gesture and said, ‘Zach.’ I laughed then at my stupidity. They were obviously giving me their names.

I gave them mine, but they seemed not to understand what I was doing. Just as the underside of the boat roared into motion, Kelly said to me, ‘Goodbye, Bobo. I love you!’

The next day, and for the remainder of the late summer moon, I had similar encounters with other humans. Strangely, they all seemed to have taken up the game played by Kelly and Zach. I learned many more human words: Lightbulb. Fish. Rifle. Bullet. Knife. Dog. Life preserver. Surfboard. Mouth. Eyes. Penis. I learned many names, too: Jake. Susan. Nika. Keegan. Ayanna. Alex. Jillian. Justine. Most of these humans called me Bobo, and sometimes for fun I returned the misnomer by exercising a willful obtuseness in persisting to think of the humans as male or female kellies.

In the vocalizations of all these many kellies, I began to pick out words that I had mastered. However, the meaning of their communications still largely eluded me. Even so, I memorized all that the kellies said, against the day that I might make sense of what still seemed like gobbledygook:

‘Bobo is back! Hey Lilly, he seems to like talking to you the best. Maybe you can use this for your college essay.’

‘Maybe I can sell the rights to all this, and they can make a movie.’

‘They say Bobo is the smartest orca anyone has ever seen.’

‘I hear he understands everything you say.’

‘Of course he’s trying to communicate with us, and he’s been getting more aggressive, too.’

‘Hey, Bobo, how does it work to mate with a whale?’

‘I’m going to play him some Radiohead. I hear he likes that.’

‘Do you just poop and pee in the water and swim through it?’

‘What do you think Bobo – is there a God?’

‘They’re saying Bobo might hurt someone or injure himself, so they might have to capture him and sell him to Sea Circus.’

‘I love Bobo, and I know he loves me.’

‘If he’s so smart, how come he can’t speak a single word of English?’

How frustrated I was! Not only did I fail to form a single human word, I could not make a single human understand the simplest orca word for water. Upon considering the problem, I realized that much of my success in recognizing the few human words I had been taught lay in the curious power of the human hand. If the humans had not been able to touch or stroke the various objects they presented to me, how would I ever have learned their names?

With this in mind, I broadened my strategy of instructing the humans in the basics of orca speech. I opened my mouth and put tongue to teeth in order to indicate the part of the body that I then named. As well, I licked a human hand and said, ‘Tentacle,’ and with a beat of my flukes I flicked a salmon into one of their boats and said, ‘Fish.’ When that did not avail, I took to nudging various things with my head and calling out sounds that I desperately wished the humans might understand: Driftwood; kelp; sandbar; clam shell. Sadly, the humans still seemed unable to grasp the meaning of what I said – or even that I was trying to teach them.

One gray morning when the sea had calmed and flattened out like the silvery-clear glass that the humans made, I came upon a small boat gliding across the bay. Quiet it was, nearly as quiet as a stealth whale stalking a seal. A lone human male dipped a double-bladed splinter of wood into the water in rhythmic strokes. A violet and green shell of excrescence encased his head. I expected his boat to be made of one of this material’s many manifestations, but when I zanged the boat, I found it was made of skin stretched over a wooden skeleton. I swam in close to make the male’s acquaintance.

‘Hello, brave human, my name is Arjuna.’ I often thought of the humans as brave, for what other land animal who swims so poorly ventures out into the ocean – and alone at that? ‘What are you called?’

This male, however, unlike most humans, remained as quiet as his boat. I came up out of the water, the better to look at him. I liked his black eyes, nearly as large and liquid and full of light as my mother’s eyes. I liked it that he sat within a skin boat. I grew so weary of listening to the echoes of excrescence, which it seemed the humans called plastic.

‘Skin,’ I called out, touching my face to the body of his boat. ‘Your boat is covered with skin, as am I, as are you!’

I did not really think I could teach him this word, any more than I had been able to teach other humans other words. Having been thwarted so many times in my increasingly desperate need to communicate, I pursued accord with this male too strenuously. My pent-up desire to teach one human one orca sound impelled me to nudge the boat as I might one of my own family. It surprised me how insubstantial the boat proved to be. I looked on in dismay as the boat flipped over like a leaf tossed by a wave.

‘Hold your breath!’ I called to the human suspended upside down beneath the boat.

Although I assumed the human must know that he would drown if he breathed water, I could not be sure. I dove beneath the water to help him.

‘Hold onto me!’

I found the male beating his stick through the water. It would have been an easy thing for him to have grasped my fin or tail so that I could pull him around through the gelid sea to return him to the air. Instead, he began beating his stick at me. He thrashed about like a frightened fish. Silver bubbles churned the water. I caught the sound of the human’s heart beating as quickly as a bird’s wings. Through the froth and the fury of the human’s struggle, I gazed at his glorious eyes, grown dark and jumping with a dread of death. Now he did not seem so brave.

‘Wait, wait, wait!’ I told him. ‘I will save you!’

I pressed my head against his side; as gently as I could, I used my much greater substance to move his slight body around and up through the water. This had the effect of turning the boat still attached to him. A moment later, the human breached and choked in a great lungful of air. Water streamed from his face and from the blue plastic skin encasing him. He coughed and sputtered out a spray of spit, for he had sucked water into his blowhole.

After a while, his coughing subsided. His belly, though, tensed up as tight as the skin that covered his little boat. And he called out to me: ‘Goddamned whale! Why can’t you leave us alone?’

Why could I not speak with the humans, I wondered as I swam off in dismay? Through days of clouds and dark nights, I swam back and forth across the bay pondering this problem. I dove deep into the inky waters, believing that if I did so, I might somehow zang how I might talk to the humans – and how, indeed, I might sound the much deeper mystery of how anything spoke with anything at all. What was language, really? For the humans, it seemed nothing more than an arbitrary set of sounds that they attached like so many barnacles to various people, objects, and ideas. From where did these sounds, though, come? What principle or passion ordered them? Could it be, as I very much wanted it to be, that the human language had a deeper structure and intelligence that I could not quite perceive? And that a higher and secret language engendered all the utterances of every individual or every species in the world? And not just of our world, Ocean, but of other worlds such as Agathange, Simoom, and Scutarix? Might there not be, at the very bottom of things, concordant and melodious, a single and universal language through which all beings could communicate?

I felt sure that they must be. One evening, as I lay in deep meditation beneath many fathoms of cold water, it came to me with all the suddenness of a bubble bursting that my approach to speaking with the humans had been all wrong. Before trying to teach them the rudiments of orca speech, which their lips, tongues, and other vocal apparatus might not be able to duplicate, might it not be possible to share with them the impulse beneath language, even as they had shared their musics with me? Yes, I decided, it would be possible. And, yes, yes, I would share with the humans all that I had so far held inside: I would drink in the deepest of breaths and gather up the greatest of inspiration, and I would sing to the humans as no whale had ever sung before!

Some days later, I entered a cove in which floated a large fishing boat. The humans had covered the front of it with gray and white paints in a shape that looked something like the head of a shark. Buoyed as I was by bonhomie and zest for the newfound possibilities of my mission, I paid little attention to the peculiarities of this boat or to the many strands of excrescence that surrounded it like intertangled growths of kelp. Nets, the humans called these fish traps. Today, however, the empty nets had trapped not a single salmon. It seemed that the many noisy humans gesticulating atop the boat had not really come here to fish, but rather to make music for me.

And what music they made! And how they made it! I swam in toward the boat, drawn by the mighty Beethoven chords that somehow sounded from beneath the water. The density of this marvelous blue substance magnified the marvel of the music. Joy, pure joy, zanged straight through my skin. I moved even closer to the boat and to the music’s mysterious source beneath the rippling waves.

‘O what a song I have for you!’ I said to the humans. I knew that if I was to touch their hearts as they had touched mine, I must go deep inside myself to speak with the monsters and the angels that dwelled there. ‘Here, humans, here, here – please listen to this song of myself!’

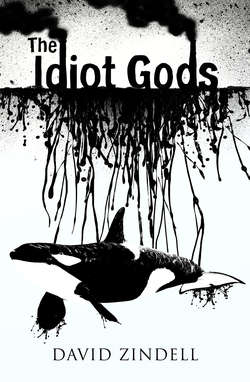

I breached and breathed in a great breath in order to sing. Before the first sound vibrated in my flute, however, the boat began to shudder and shake and to issue sounds of its own. The air sickened with a clanking and grinding. Quicker than I could believe, the nets of excrescence began closing in on me from all sides, like a pack of sharks intent on a feeding frenzy. My heart leaped, not with song but with a fire like that which had burned the waters of the northern sea. I swam to the east, but encountered a web of excrescence in that direction. A dart to the west led straight into yet more netting. I dove, seeking a way beneath the closing nets, but I could not find an escape to the open ocean. In a rage to get away, I swam down through the bitter blue water and then hurled myself in steep arc into the air and over the shrinking sweep of the net. I plunged down with a great splash. For a moment, I thought I was free. It turned out, though, that I had landed within a second layer of netting, which quickly ensnared my tail and fins. The humans – the insightful, intelligent, and treacherous human beings – had considered very carefully how to trap a whale such as I.

As the net tightened around me and pulled me toward the boat and the flensing knives and the teeth that must await me there, I began singing a different song than I had intended: the thunderous and terrible universal song of death that I knew the humans would understand all too well.