Читать книгу The Idiot Gods - David Zindell, David Zindell - Страница 7

Translators’ Note

ОглавлениеIt was our privilege and happy destiny to enjoy the friendship of one of the most remarkable beings ever to have come out of our little blue and white planet. Many have tried to make the orca named Arjuna into a Buddha or a Jesus, but he certainly never thought of himself as such – and not even as a teacher. Despite all insistence to the contrary, he remains an orca, however extraordinary, with all an orca’s sometimes strange and disturbing sensibilities. It is true that those who spent time with him often forgot that they were conversing with a cetacean possessing a magnitude of intelligence that we are still trying to comprehend. The consciousness of all creatures differs so greatly, yet at its source remains one and the same, as of a white light shined through a prism and refracted it into radiances of red, yellow, violet, and blue. Arjuna’s consciousness, to the extent that it illuminates his communications, can often seem pellucidly and sanely human, and at other times, psychopathic or utterly alien. We who have translated his ‘words’ faced the problem of necessarily regarding a non-human being through very human eyes; we have tried to convey a sense of Arjuna’s magnificent soul without making him seem too human. It would be well for anyone to see Arjuna for what he really is: a whale who just wanted to talk to human beings.

That Arjuna, born in the cold ocean, could have learned to ‘speak’ various human languages many still doubt, even after the seemingly miraculous events the whole world witnessed. They say that we linguists and biologists of the Institute for Advanced Cetacean Studies either misconstrued basic hunting, mating, or warning cries as language or interpreted them through our natural wish to communicate with an obviously intelligent but nevertheless inarticulate animal. Human beings, these skeptics believe, are by definition the only of earth’s creatures capable of symbolic and therefore true language. Our harshest critics – and we should hesitate before calling then conspiracy formulators – have accused us of simply inventing our translations of the thousands of communications that the orcas of the Institute confided in us. They accuse us of conspiring to excite compassion for these great beings toward the vain hope of ‘saving the whales’. This account is not for those deniers. Even if one were to read Arjuna’s account as a fiction, however, one should keep in mind that fictions often reveal the deepest of truths. In many ways, this is the truest story we know, and Arjuna had the truest of hearts. Anyone eager to know more about his life will lose little in skipping this introduction and going right to the words Arjuna chose to convey it. It is indeed a remarkable story. In the end, it is his story, and ours: that of the whole human race.

We would like to say more about those words that Arjuna selected to denote meanings that human beings could comprehend. In no way should these be considered to be ‘whale words’; whales do not communicate to each other through what we know as words, but rather through sound pictures. Arjuna offers as good an explanation of cetacean language as we could hope, and we cannot improve it. Sadly, we know almost nothing of what we sometimes informally call Orcalish. To date, even with the aid of the fastest of computers and the most elegant of mathematical models, we have managed to identify and interpret perhaps a twelfth of a percent of the meanings of the thousands of orca utterances. It should be remembered that we human beings still have not learned to speak with the whales, though they have readily, if painfully, learned to speak with us.

How, then, did Arjuna and the other orcas of his adopted family accomplish such a feat? The Institute’s former chief linguist, Helen Agar, initially worked with him in developing a constructed language through which orcas and humans could communicate. Various utterances natural to orcas – whistles, trills, clicks, chirrups, pulsed calls, and pops – were agreed upon to represent the ninety-one syllables of the language that Arjuna named Wordsong. Helen Agar had no need to speak Wordsong to Arjuna, for he understood English (and many other human languages) very well; however, while engaged in natural communication with Arjuna and the other orcas, Helen chose to communicate in this imaginative language out of solidarity with the whales and the ideal of making the crude vowels and consonants of a human language somehow ‘sing.’ Only one of the Institute’s other linguists (Prasad Choudhary) reached fluency in this language that has been popularly mischaracterized as ‘Baby Orcalish.’ In reality, Wordsong is more like a spoken Morse Code. It assigns meanings to orca sounds usually employed by the orcas very differently. Anyone can ‘talk’ Morse Code, for instance saying, ‘Pop, pop, pop; sprong, sprong, sprong; pop, pop, pop,’ to denote the SOS message meaning ‘help.’ While conversing in Wordsong is much more difficult, the rules for doing so follow a similar principle. Alone of non-linguists, the orca trainer Gabrielle Jones did come to understand Wordsong when Arjuna spoke it to her, even if she was unable to speak it back to him. English remained her only language, and it was she who encouraged Arjuna to communicate to the human race in what has become a de facto, if very limited, world language.

Most of Arjuna’s story, then, he recorded in English through an extension and adaptation of the Wordsong’s syllabary to English. As English contains, by some counts, more than 15,000 syllables, not even Helen Agar came close to understanding Arjuna when he was speaking it. Instead, as we have continued to do, she relied on the Institute’s computers to translate Arjuna’s vocalizations into more or less standard English.

This last statement must be qualified. When Arjuna could not find the word he wanted in the language of Shakespeare, Blake, and Eliot, he turned to others, peppering his account with words from Spanish, Japanese, Diné, Arabic, and Basque – and even from Quenya, Fravashi, and one of the many dialects of Tlön. He particularly liked Chinese for its tones and !Xoon for its clicks. All these needed to be re-translated into English; and even his English needed extensive editing. While his locutions at times could be eloquent and even poetic, they contained many quirks, for instance incorporating his curious prejudice against using contractions. Because orcas in their own language, as far as we can understand, transcend time through obscuring the boundaries between past, present, and future, Arjuna liked to meld together different diction levels and styles from different periods of human history. Bizarrely, he rendered entire sections of his communication of the story of his life into somewhat turgid verse aping the Latinate cadences of John Milton’s Paradise Lost.

All this needed smoothing into prose accessible to those Arjuna most wanted to address. [The Institute has published the original document in all its babel of magnificence for anyone capable of deciphering it in hopes of reaching a deeper understanding of Arjuna’s mind.] As well, we took the liberty of cutting many strained metaphors and converting sound imagery to sight imagery, which predominated throughout the original document in a ratio of 77 to 23. Human beings, as Arjuna realized very early, are creatures of sight, and he would not have minded our attempts to make his story as readable as possible.

We found it more difficult and too distracting in the published English document to add cites in the many places where Arjuna ‘borrowed’ the sensibilities or the words of human authors. [The entire footnoted document is available upon request.] Arjuna plagiarized without shame. He considered copying or paraphrasing another’s words as honoring dead authors. He had no sense of property, either intellectual or any other kind. The only thing orcas ‘own’ are the compositions of themselves, which they call rhapsodies – and in a way, not even those, since the songs of all orcas belong to their families in much the same way that their souls belong to the sea.

Similarly, we hesitated to cut or change the many repetitions, such as Arjuna’s overuse of the words ‘splendor’ and ‘song’ – and most particularly, ‘soul.’ Arjuna found it difficult to settle on a single English word that could encompass a fluid orca concept. Certainly, he meant by soul many of the same things we usually call by different names but regard as intrinsic to ourselves: personality, memory, mind. In no way, however, did he intend soul to connote some sort of immaterial or supernatural essence. He might just as easily have used the words song, water, or wave. For orcas, soul is a substance no different than the water that forms up on the surface of the sea from which the whales take their greater being. If the orcas could be said to have a goal that they seek to achieve, it would be the shaping of themselves into perfect waves that share the same water of life with all others. So vital is this imperative to bring forth the most beautiful manifestation of true nature that Arjuna speaks of the soul dozens of times. He liked to say that he was involved with the soul of humankind.

Of course, Orcas don’t mind repetition in their communications to each other. Or rather, the nature of the orcas’ ever-flowing language, as far as we understand it, makes boring repetitions nearly impossible, in much the same way it is impossible to step twice into the same surging stream. Each sound picture that an orca paints – even one so commonplace as that of a salmon – differs from all others in nuance, inflection, and the many colors of sound. The nearly infinite complexity of these sound pictures, like variations of themes in an open-ended cerebral symphony, engages an orca’s full attention at the same time that it discourages human examination. Sadly, human beings remain bound to essentially one-dimensional sequences of syllables spoken in time, and despite Arjuna’s assurances to the contrary, it is extremely unlikely that we will ever comprehend the three-dimensional language of the whales. We simply don’t have the mental machinery to do so.

More must be said about the human brain – its deficiencies and limitations – in comparison with the brains of orcas and other toothed whales. The mammalian brain has been built up by evolution in layers over millions of years. The foundational structure, the primordial paleocortex or reptile brain (called the rhinic), recalls the similar structures of the brains of fish, amphibians, and reptiles such as lizards and snakes. (Though it must be stressed that this does not imply that mammals evolved from reptiles, for instance, any more than humans did from chimpanzees. Both mammals and reptiles share a common ancestor in the Carboniferous period 300 million years ago.) The limbic lobe overlays this structure, as the supralimbic lobe does both. The outer lamination of brain matter is called the§ neocortex, whose growth over vast periods of time has enabled the leaps in intelligence of the mammals.

This ‘new brain’ – with its convolutions, fissures, and folds somewhat resembling those of a shelled walnut – is the pride of humanity. The brains of no other creature, it was thought for a long time, approach those of the human in differentiation, neural connectivity, sectional specialization, complexity, and power. Few of our kind have welcomed the discovery that the orcas’ (and other whales’) gyrification exceeds that of human beings. The surface area of a typical adult human’s neocortex measures about 2,275 cm2, while in dolphins, it is 3,745 cm2, and in orcas and sperm whales much greater. It is true that the orca neocortex is thinner than the human, but there is simply more of it folded up with greater complexity. To add insult to the injury of wounded human vanity is the fact that orca brains weigh in at three times the size of human brains – and the brains of sperm whales exceed in size our own by a factor of six.

For many decades, various scientists have thought to obscure this glaring and embarrassing reality. They have conjured up various ‘fudge factors’ in a desperate attempt to ensure than human beings will be number one in any ranking of species’ relative intelligence. Arjuna, in his account, with a simple thought experiment, demolishes the long-respected though ridiculous brain/body mass ratio as a measure of intelligence. (If this ratio proved true, the hummingbird would be the world’s smartest animal.) Realizing the limitations of the older metric, so-called scientists have invented a new one: the Encephalization Quotient (EQ), which measures the actual brain mass against the predicted brain mass for an animal of a given size. Of course, human beings with our large brains relative to our small bodies, again, come out on top. This, however, is not science; it is bosh. First, and most importantly, absent a method of universally measuring intelligence and correlating it with the EQ, it is just another voodoo statistic, sounding impressive but possessing no meaning. Second, while the EQ does an excellent job of fulfilling its purpose of distinguishing human intelligence from that of supposedly lesser beings, it fails in providing meaningful comparisons among other species. For example, the EQ of a capuchin monkey, about two, more than doubles that of supposedly much smarter gorillas and chimpanzees. Third, if some species are over-encephalized, mathematics necessitates that some species must be under-encephalized, therefore lacking the mental machinery to perform the basic cognitive functions necessary for survival. The usage of the EQ attempts to obscure the rather obvious fact that only a certain percentage of the brain is used to operate the gross functionings of the body, no matter how large (or small) that body might be. As it turns out, very little amounts of brain can account for rather amazing powers of muscle, bone, feather, and flesh. The peregrine falcon, the fastest bird in the sky, manages to perform its aerial acrobatics and compute its 250mph dives through the air to catch a darting dove by virtue of a brain the size of a peanut.

A better question, too little asked when considering what we think of as intelligence, would be to inquire how much of an animal’s brain can be devoted to the interconnectivity and association of ideas? In rats, this associative skill has been measured at approximately 10%. A cat tests out at 50% while a chimpanzee scores a 75%. Human beings, at 90%, thus need only 10% of our brains to operate our sensory and motive capabilities. What about the whales? The average associative skill measure estimated for cetaceans, at 96%, much exceeds our own, while orcas have available approximately 97.5% of their very large brains for a very wide range of cognitive functions.

More recently, Suzana Herculano-Houzel has argued in favor of another way to estimate intelligence, hitherto impossible to measure correctly. Citing the work of Williams and Herrup, she points out the reasonableness of assuming that the computational capacity of the brain should correlate with the absolute number of neurons in that brain, specifically in the neocortex, the supposed seat of animals’ higher cognitive abilities. How, though, to actually count the number of neurons in a brain?

In a brilliant piece of science, Herculano-Houzel succeeded in using detergent to dissolve the brains of various species to make a ‘brain soup’ in which neurons’ nuclei could be separated out and counted. The computations that resulted cleared up several mysteries. It turned out, for instance, that the elephant, with a brain more than three times as massive as that of the human being, does have more neurons; about 257 billion neurons compared to a human’s 86 billion. However, 98% of those neurons are to be found in the cerebellum; the elephant’s cerebrum contains a paltry 5.6 billion neurons compared to the 16 billion in the human cerebral cortex. That seems to explain our experience that human beings are a good deal smarter than the admittedly still-smart elephant. As Herculano-Houzel likes to say, ‘Not all brains are made the same.’ As she puts it, brains scale differently in different species and in different orders. The primate brain, and particularly the human brain, has evolved to pack more neurons more efficiently into a smaller volume, thus giving humans an advantage in intelligence over other species.

What, then, of the whales? Cetaceans share a rather close phylogenetic relationship with Artiodactyls such as pigs, deer, and giraffes. Based upon the scaling for those species, Herculano-Houzel predicted that the count of neurons in the much larger cerebral cortexes of several kinds of cetaceans would actually come out to a significantly lower number than that of humans. The largest cetacean cortex, that of the sperm whale, would contain fewer than 10 billion neurons, still much less than that of a human. It seemed that human beings’ ranking of number one would remain unchallenged.

There the matter stood until a whale hunt happened to deliver the brains of ten long-finned pilot whales into researchers’ hands. Using the techniques of optical dissector stereology, it was discovered that the neurons in the pilot whale neocortex numbered 37.2 billion – more than twice the human’s 16 billion. Heidi S. Mortensen, Bente Pakkenberg, and five others described the quantitative relationships in the delphinid neocortex in a paper published in Frontiers of Neuroanatomy. Their discovery should rank among the greatest in importance in the history of science. Instead, this very great breakthrough remains largely unknown. The cortical neurons of the orca have yet to be counted, but it would not be surprising if they topped out at over 75 billion.

As if all this weren’t enough to dethrone Man as the King of Creation, one more humbling discovery should be considered. In addition to the previously mentioned three primary structures of the mammalian brain – the rhinic, the limbic, and the supralimbic – cetaceans have evolved a fourth cortical lobe absent in any land mammal, human beings included. Although we do not yet know the precise functioning of this paralimbic lobe, it has been speculated that it integrates and enhances perceptions of sound, sight, taste, and touch. This would make sense of the orcas’ synesthetic powers, what Arjuna calls ‘the fiery splendor of sound and the music of light.’ It may also have something to do with orientation in space and time and the orcas’ perception that they can journey at will through the one as readily as the other.

Given the limitations of science and our ignorance of what really goes on inside the minds of whales, we believe that it would be as silly to try to calculate the cetaceans’ intelligence as it would be to count the number of angels that can dance on the head of a pin. Were one to attempt to do so, however, considering the enormous size of the cetacean brain, considering its differentiation, sectional specialization, neural connectivity, and complexity (to say nothing of various orca feats such as the truly astounding acquisition of numerous languages), it would be enticing to come up with a rather large number. If the average human IQ can be measured at 100, with Economics Nobel Prize winners at 153 and geniuses on the order of an Einstein or a Goethe perhaps coming out at around 200, then an orca would score five times that while a sperm whale topped out at over 2,000.

What do orcas do with such massive intelligence? We have already mentioned their astonishing ability to learn languages (a sponge absorbing water is not an inaccurate metaphor), and Arjuna has much to say about the musical/philosophical compositions that the orcas call rhapsodies. All the whales have powers of the mind of which we have only the dimmest of intimations. How else can the seeming Miracle of the Solstice be explained? The speed of sound in water at 20 degrees Celsius is 1,482 meters per second – far too slow to account for what otherwise can be explained only by positing some sort of instantaneous planetary communication.

That we must accept the existence of certain so far inexplicable abilities and phenomena in the lives of whales does not imply that we should not question Arjuna’s interpretation of some of them. What are we to make of the impossible creatures that he calls the Seveners? Certainly many strange species dwell as yet undiscovered in the vast reaches of the oceans. In many ways, we know much more about planets millions of miles from earth than we do the perpetually dark deeps of our own oceans. Could a complex animal assemble itself out of tiny multi-cellular organisms in a matter of minutes? Could such a creature possess the sort of intelligence that Arjuna accords it?

To the first question, we have a hint of an answer in the pyrosomes: colonies of thousands of zooids a few millimeters in size that associate with each other in huge, bioluminescent tubes up to twenty meters long and two meters in diameter – capacious enough to fit a grown human being inside. To the second question, we must incline toward a resounding ‘no’ because pyrosomes and any other conceivably similar species are not complex and lack anything resembling a brain.

And yet. And yet. Compendiums of findings about the Plantae kingdom (see Tompkins’s and Bird’s The Secret Life of Plants and Mancuso’s and Viola’s Brilliant Green) suggest that trees, flowers, ferns, mosses, and the like can be said to possess a real intelligence completely absent in a brain. And then there is the recent discovery of bacteria that might need to be classified as an entirely new and seventh kingdom of life. It seems that the species of Geobacter metallireducens and Shewanella, found in certain estuaries and other aquatic environments, have evolved to strip and deposit electrons from metals and various minerals, thereby essentially eating and breathing electricity. As well, they have the ability to interconnect with each other in ‘cables’ of thousands of individual cells. It is thought that this association is facilitated by ‘nanowires’ that are an extension of the cell membrane and which can conduct electricity in a biological circuit.

Might Arjuna’s Seveners be some sort of very intelligent colonial organism assembled from bacteria similar to Geobacter metallireducens and Shewanella? We have no evidence of that, and we are skeptical that such a creature either does or could exist. It seems much more likely that Arjuna encountered (and ate) some sort of organism whose tissues produce alkaloids similar to those found in Psilocybe cubensis or Lophophora willamsii. Very intense hallucinations would account for Arjuna’s insistence that what he experienced in the South Pacific was as real as his birth or any other event of his remarkable life.

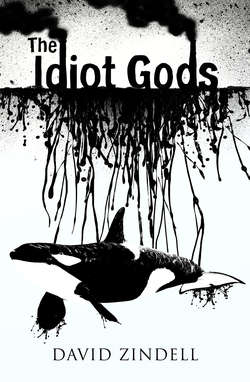

Before closing this introduction to that life, we would like to say something about two terms that Arjuna uses at various times throughout his account. The first is the name he often used to describe human beings: the idiot gods. He thought long and deep before deciding on this sobriquet. At times, he thought it much more apt to call our species the mad gods or the insane gods. However, madness can too easily be associated with anger, and although Arjuna certainly saw human beings as afflicted with wrath, as a rabid dog is lyssavirus, he did not see this as humanity’s greatest sin. Neither did he think of our kind as purely insane. Rather, he perceived in our derangement of sense and soul a willful debilitation, as if we human beings are an entire race of sleepwalkers moving through a nightmare from which we refuse to awaken. We are, he once said, like lost children wandering through a dark landscape without markers or boundaries. He had great compassion for (and dread of) our innocence. Given the horrors that Arjuna recounts, that seems a strange word to apply to the human kind, but it motivates his choice to call us idiots. It is the holy fool kind of innocence of Prince Myshkin in Dostoevsky’s The Idiot as well as the deadly innocence of the young man Lone in Sturgeon’s The Fabulous Idiot, incorporated into the great work known as More Than Human. Of all humanity’s failings that Arjuna enumerates in such painstaking and painful detail, he counts as the very worst our refusal to embrace our best possibilities and so to live as gods.

The second term we would like to define is quenge, the most quintessential part of a whale’s true nature. Arjuna himself coined the word to represent a nearly ineffable cetacean sensibility and prowess. We would like to explain this strange word, though of course it remains inexplicable. One might as well try to describe a magnificent city on a hill, bright with sunlit cathedrals and great spires, to a band of cave-dwellers. The best course for anyone wishing to know more is to make one’s way into Arjuna’s story. But please do so with an open mind, and even more, with an open heart. Readers who reach the end without having any idea of what it is to quenge will have wasted their time – and Arjuna’s.