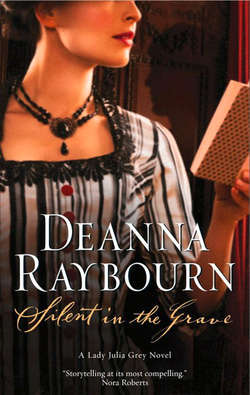

Читать книгу Silent In The Grave - Deanna Raybourn, Deanna Raybourn - Страница 11

THE SIXTH CHAPTER

ОглавлениеFor sweetest things turn sourest by their deeds; Lilies that fester smell far worse than weeds.

—William Shakespeare

“Sonnet 94”

Of course, it did not seem like anything of an adventure at the time. Despite Portia’s efforts with my appearance, I still spent most of my time at Grey House, reading to Simon, listening to Aunt Ursula detail her newest remedy for constipation, or waiting for Val to return home from his evergrowing number of social engagements. My year of widowhood was nearly at an end and I was beginning to chafe under the restrictions. I had not been to the theatre or the opera since Edward’s death. I had not entertained, and had been invited to only the most intimate of family parties. I felt sometimes as though I might as well have been locked up in a Musselman’s harim considering how little I was actually outside of Grey House.

As for Portia’s suggestion that I take a lover, the very idea was laughable. I saw few men, save those I employed or to whom I was related by blood or marriage. I had only the notion of Italy to sustain me. I had mapped out my plans to the last detail, dispatching letters to delightful innkeepers and receiving particulars on their accommodations. I had applied myself diligently to the study of Italian, and with Simon to tutor me I made rather good progress. He had always had a good ear for languages, and was enormously patient with my mistakes.

“You are a natural,” he told me more than once. “I could close my eyes and believe you were Venetian.”

“Liar,” I said happily.

And we were happy, I think, in spite of his bouts of breathlessness and the fevers that left him too weak to hold a book. I used to look up quickly and catch him, a hand pressed quietly to his chest as he stilled his jagged breathing. But even then he would not forgo our lesson.

“It is all up here, my darling,” he said, tapping his brow. “Now, tell me, how would you say, ‘these gardens are beautiful’?”

“Questi giardini sono belli,” I replied.

“Very good. Now ask what sort of tree this is.”

“Che albero è questo? But Simon, I’m not terribly interested in trees, I’m afraid.”

He smiled up at me, his face pink with exertion and pleasure. “Ah, Julia. You are going to Italy. You must be interested in everything. You must be open to every possibility.”

Strange that both he and Portia should parrot the same theme. Change, possibility, opportunity … but as I looked at Simon, I remembered that this particular opportunity would not come my way until he had passed from my life.

I think he remembered it, too, for he looked away then and told me to begin counting, a skill I had mastered a month before.

It did not matter. It was something safe to speak of when we dared not speak of other things.

“Uno, due, tre …”

And so the year passed away, dully, though not entirely unpleasantly, until the April morning I decided to clean out Edward’s desk. I had not entered his study in months, certain that the maids were keeping it tidy, but now, as the spring sunlight streamed into the room for the first time in weeks, I saw what a halfhearted effort they had made.

Stacks of books and old correspondence remained where Edward had left them, organized in his own peculiar system and bound with coloured tapes. I had leafed through them once to make certain that the letters did not require a response—and for any sign of the notes Mr. Brisbane had mentioned as well. I had found nothing. I had been relieved, so relieved that I had simply shut the room up and left it, much as I had left his bedchamber and dressing room. It had been very easy to turn my attention to more pressing matters, and very easy to convince myself that anything was more pressing than sorting Edward’s things. The spring had been a wet one, and I had spent many long hours curled in my old dressing gown, lazing by the fire with a book. But days of chilly rain had given way to watery sunshine, cold, but nonetheless bright, and I was determined to take advantage of it. I ordered a pot of fresh tea and a plate of sandwiches and set to work.

An hour later I had made quite good progress. The papers were sorted, the books organized and the sandwiches almost all eaten. Only the drawers themselves were left.

Briskly, I set to work, emptying the contents of the tightly packed drawers onto the desk. There was little Edward had not saved. Programs from theatre evenings, his private betting book, ticket stubs, letters dating back several years at least. His account books had been given over to the solicitors, but everything else was still packed into those five drawers. I went through them all, sorting the detritus to be burned and the few small tokens worth keeping. It was painful and sad to reduce a man to a handful of things—among them a pen with a nub broken to his hand. I should have thrown that away; it never wrote properly for me, skipping and stuttering ink across the page. There was a thin volume of poetry I did not remember him owning, a small sketch he had made of a ruined courtyard long forgotten, a broken watch chain, a molting black feather. A few bits and bobs, and nothing of importance, I realized sadly. The rest was tipped into a basket for rubbish to be hauled away by one of the footmen. The drawers fresh and empty, I prepared to replace them back onto their runners. I had never cared for the desk itself—it was a very large piece, thick with Jacobean carving, but it would likely fetch a good price at auction.

I had just slotted the last drawer into place when I realized that it would not shut. I pushed at it again, but it was caught on something and I pulled it out. My fingers touched a tightly wedged twist of paper, far at the back, hidden in shadow. I worked at it a moment with my fingers and a paper knife before I wrested it loose. A program from the opera, like a dozen others, scribbled over with the names of likely horses. I turned it over, and from inside its leaves fell a small piece of paper, violently creased, as though it had been thrust into the progam in a tremendous hurry and stuffed at the back of the drawer. I smoothed it out, thinking that it was very probably a scrap of a poem that Edward wanted to remember or a note to try a particular wine.

But I was very wrong. It was plain paper, inexpensive, with a bit of verse cut from a book pasted onto it.

“Let me not be ashamed, O Lord; for I have called upon Thee; let the wicked be ashamed, and let them be silent in the grave.”

Below it was a rough drawing in pen and ink, only a few lines, but its shape was unmistakable. It was a coffin. And on the stone sketched at its head was a tiny inscription.

Edward Grey. 1854-1886. Now he is silent.

I stared at the page, wishing fervently that I had never found it. Although Mr. Brisbane had never described the notes to me, I felt certain that I had found one. And having seen one, I was also certain that Portia was wrong—this was no jest. Malice fairly emanated from the paper.

I held on to it for a long time, fighting the temptation to throw it into the wastepaper basket and let the footman cart it away to be burned. I could not simply crumple it back into the depths of the desk, pretending I had not found it at all. It would linger there, like a canker, and I knew that my fingers would go to it again and again. No, if I were going to be rid of it, it must be destroyed entirely. I could do it myself, I realized with a glance at the brisk fire crackling away on the grate. No one would ever know—it was a small thing; it would be consumed in a matter of seconds.

But no amount of burning would change what I had seen. And having seen it, I could not forget what it meant. Someone had wished Edward dead, enough to terrorize him with vicious notes, making his last days fearful ones. At the very least, the sender of these notes had harmed his peace of mind.

But what else might this malicious hand have done? Had it done murder? I would never have credited such a thought had Nicholas Brisbane not put it into my mind, but there it was. Edward was a perfect victim in so many ways. He was very nearly the last member of a family famed for its ill health. Neither his father nor grandfather had lived to see thirty-five. Edward was almost thirty-two. He had never been robust, even as a child. And in the year before his death, his health had grown dramatically worse, manifesting the same symptoms that had taken his grandfather and father before him. It would be a small matter to introduce some poison to such a delicate constitution; perhaps it would even work more quickly on one so weakened by poor health. How simple it would have been for some unknown villain to send along a box of chocolates or a bottle of wine laced with something unspeakable.

But why the notes, then? Would they not serve as a warning to Edward? He would have been on his guard, surely, against such an attack. Or would he have been naive enough to believe that his murderer would strike openly, that he would have a chance to defend himself? I knew nothing of his thoughts, his fears during those days. Edward kept no diary, no written record of his days. And he had clearly felt incapable of confiding in me, I thought bitterly.

I looked at my hands and realized that I must have already decided upon a course of action whether I realized it or not. I had folded the note carefully and placed it in a plain envelope. There was only one person to whom I could turn now.