Читать книгу Fat Chance - Deborah Blumenthal - Страница 9

two

ОглавлениеTo know Tex Ramsey is to love him. I’m perched on the corner of the Metro desk—he’s the big honcho, Metro editor—with my legs crossed coquettishly, chewing a wad of purple bubble gum to get myself noticed, reading People magazine and waiting. You always have to wait for Tex, especially when it’s dinnertime. It’s not that he doesn’t have an appetite. Just the opposite. It’s just that dinnertime is synonymous with deadline, and the phone next to him rings constantly. He glares at it momentarily and then looks back at the computer screen.

“Don’t we have a secretary around here?”

“Out sick, Tex.”

“Sick of what, this joint? Anyone think to call a temp?”

“Don’t think.”

Business as usual.

“T E X, you cut half the story,” the police reporter’s whine fills the room. “I spent three hours with the commissioner and you give me four hundred words?”

“No space. We’ll do a follow.”

“Follow? He won’t spit at me after this abortion.”

“Bring me a hankie.”

A general assignment reporter shows up next, a Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism graduate, with no obvious pathology, who in two short years at the paper has developed a tic. He’s smacking a copy of the newspaper against his hand in fury and grousing about a typo in his story about a hero cop. He closes his eyes, dropping his head in despair.

“We said he’s been with the department for ONE HUNDRED years.”

“Only an extra zero,” Tex says, waving it away with his hand. “Look at the bright side. Now the department thinks they owe him 90 years of back pay, the guy’s rich, and he’s eligible for immediate retirement.”

He winks at me, then fogs his glasses, wiping them on the sleeve of his shirt, before turning back to the lead story on his screen about a supposed affair between the mayor and his press secretary. At the press briefing, they decided, uncharacteristically, to take the high road and play it down, hiding it deep inside. The mayor already hated the press. They had alienated him sufficiently with their in-depth probe right before the election. But now that every gossipmonger in the city had weighed in, it would be the cover.

Tex stretches his legs up over the desk, crossing his scuffed Tony Lamas. “Here’s our head: CITY HALL HOTBED. What the hell—it would sell papers. If the megalomaniac mayor couldn’t stand the…”

“I’m starving….” I sing out sweetly. “Ribs encrusted with honey and teriyaki glaze.” I dangle the thought before him. If that doesn’t work, I’m going to start filing my nails. Bingo. He looks out at the copy desk.

“Okay, bro’s, put it to bed. I’ll be at Virgil’s if you need me.”

“You and Maggie eatin’ Pritikin again, eh?”

Tex snorts. “Not likely. No spinach salads and Diet Sprites for her,” he says, punching my arm. “She’s the only girl I ever met who knows how to eat.” That’s a compliment, I think. He grabs his coat and we hail a cab. I can’t wait to tell him about California.

I gnaw off all of the red caramelized beef on the baby back ribs and then soak up the remaining droplets of amber glaze on my plate with a slab of doughy bread. The oval platter between us that had been heaped with crisp golden brown shoestring fries is now bare except for a sprinkling of burned crumbs and flakes of coarse salt.

I lean back on the thick wine velvet banquette and sigh. “So then the phone rings, and guess who called yours truly?”

“The papal nuncio?”

“Negative.”

“Temptation Island?”

“No, and I’ll spare you your remaining eighteen questions. A hotshot from L.A. who wants me to fly out there and help with a movie they’re making.”

Tex closes his eyes and looks down. “You’re such a pushover. It was Alan Barsky.”

“It was not Alan Barsky.”

“How can you be so sure?”

“Alan Barsky would have said he was Steven Spielberg.”

“Hmmm…I see your point…so what did you say?”

“I said I’d drop everything and be there in a heartbeat.”

Tex guffaws. “They sending a Lear?”

“No, a Peter Pan Bus ticket.”

He shrugs. “Hell…you’re on a roll, why not? You’ve got the media eating out of your hand, go for it. It could beef up your career even more. Celebrity fat columnist reaches to the stars. Definitely a sound career move.”

I’m suspicious now. “Why are you so gung ho?” I can’t help but think of Tex as, well, my protector. Maybe it’s his build. Former star tackle—the kind of guy who’d smile as he was hauling your couch up a flight of stairs. He hoists his beer bottle and drains it. That’s the sum total of his daily exercise, not counting the jaw work of the job.

“You’ll be the next IT girl and I can say I knew you when.”

“Naw, it’s not me…. I’ll just forget the whole thing,” I say, flicking bread crumbs into a miniature replica of the pyramid at Giza. “I mean, even though it probably means mega bucks—you know how these movie companies pay consultant fees when they want help—I despise L.A. anyway. I mean who doesn’t?”

“Remember that Woody Allen movie?” He works at keeping a straight face, but his own stories always set him off. He leans back into the seat to get more comfortable before he starts spinning the yarn.

“You know where he’s in the car with Tony Roberts who’s got on this space-age, silver Mylar jumpsuit? Roberts zips up the hood that just about engulfs his entire head, like he’s going to be launched to Mars, and Woody turns to him, deadpan, and asks, ‘Are we driving through plutonium?’” Tex almost doubles over with his loud, roaring laughter. I give him a small tolerant smile.

“Yeah, the clothes, the cars, you can’t walk anywhere,” I say, “except for the treadmill in your home gym. And then there’s the Freeway. What an oxymoron. The Freeway, where you sit in traffic, looking at the guy in the next lane. How did he get that car? What does he have that you don’t? The car and the phone, the phone and the car, that’s their whole shtick. I think they all have phones jammed up their asses, I swear. What a disgusting way of life!”

“Maybe you’ll get into it, who knows?”

I look at Tex and wonder. What if he got a call from, say, someone like Gwyneth Paltrow or Kim Basinger asking him, in a breathy voice, if he could tutor her for an upcoming role as a newspaper editor? Would he go? I can only imagine his reply. “Let ’em try.”

“So,” he says, slapping his hand on the table, “how about we go to that Italian bakery on Third Avenue for tiramisu?”

We walk across town and up Madison Avenue. The trees in front of the Giorgio Armani shop are laced with tiny sapphire Christmas lights, arboretum couture, while window-lit mannequins wear strapless gowns and tuxedos of tissue-thin silks and crepes, and high-heeled sling-backs encrusted with ruby crystals. We pass candlelit restaurants where dark-haired men with romantic eyes face blondes in white wool suits with minks draped over the backs of their chairs, while just outside on frosty street corners open to the sharp wind lie vagrants with unkempt hair under cardboard shelters offering bent paper cups for spare change. The fragmented New York mosaic.

For all its opulence, and all its shortcomings, the city tapestry seduces me. Why would I want to leave it for L.A.? Who wants to spend half a day flying out to a place where nobody thought about anything but competing for parts and coveting awards for pretending that you were someone you weren’t? They were all bent out of shape, pretentious. The whole damn place was pretentious.

We walk to Third Avenue, passing the Tower East movie theater and a Victoria’s Secret. The long expanse of windows is devoted to sherbet-colored Miracle Bras that can incrementally ratchet up your cleavage, a “have it your way” for bras instead of burgers. They’re paired with matching thongs as sheer as snowflakes. I’m watching Tex.

“So what was the name of the movie anyway?” he says, raking a hand through his dark, curly hair as he finally turns from a blond mannequin in a sea-green thong.

“What movie?”

He shakes his head in disbelief. “The one they asked you to help on, darlin’.”

“Oh…. I forgot…. Hmmm…dangerous, dangerous something…oh…I think Dangerous Ways, Dangerous Lies. That was it.”

“Gossip’s doing an item on it tomorrow,” he says offhandedly, and snorts. “The sleazy jerk who’s starring in it has this global fan club that issues daily reports on ‘sightings,’” he says. “Get this. Never mind that he was busted once for drunk driving, and likes coke, Hollywood doesn’t hold that against him. They paid him twenty mil for his last movie. And you know what he tells Cindy?”

I shake my head.

“‘Money doesn’t mean that much to me. It doesn’t buy spiritual fulfillment. It’s something that you barter with. It has no intrinsic worth.’” He laughs out loud. “I’m going to use that on my landlord when he asks for the rent,” he says, deadpan. “‘It has no intrinsic worth.’”

For some reason my skin is starting to prickle. “Exactly who are you talking about?”

“The guy from that TV show…that hustler astronaut from The High Life.”

I slow my pace. “What?”

“Yeah,” he says. “Gelled hair, what’s his name?”

“Mike Taylor?”

“Yeah.”

I’ve fallen out of step with him now, dragging my feet. “Would you mind if I took a rain check on dessert?”

“You okay? You’re lookin’ a little pale.”

“I’m fine…it’s just been a really long day, and suddenly it’s all hitting me.”

Later on, I sit back and go over my phone messages. Shortly after I started the column, my phone started ringing with offers to do TV. Initially, I ducked them. How would it feel to be in front of the TV camera? I had this frightening scenario in my head: I was in an electronics store and everywhere I looked I saw my full face on all the screens of the demo models. Twenty different Maggies, starting with a ten-inch screen, graduating up to one the size of the eight-story Sony Imax screen, all in different gradations of harsh, artificial color. A too-red me, a pink-and-fuchsia me, a yellow-green me, a harsh black-and-white version, all color leached out. A flat-screened Maggie, a fat-screened Maggie. A United Nations of Maggie O’Learys. A fun-house house of horror come to life. Halloween. The vision makes me cringe.

Then there’s the business of speaking my mind without the safety net of print. Would I start to stutter and stammer? Could happen. There was no delete key on a live TV show, and I wasn’t used to expressing myself in sound bites. It was safe to work behind a computer screen. But ultimately, what it came down to was that I was never one to retreat in the face of a challenge…so…

First stop on the AM with Susie show is makeup. They redden my cheeks, add more lipstick to return the color that the lights wash out, then dust me with a giant powder brush to cut the shine. I’m ushered into the studio, and seated in front of the audience. The camera rolls up, the eyes of America are on me, and I feel as though the spotlight will imbue my words with greater meaning. I envision viewers alone in their kitchens or bedrooms, sipping coffee and eating coffee cake. They stop in the middle of paying bills or maybe cleaning the sink, hoping to come away with some moral or inspiration that will elevate them from the state of feeling disembodied, alienated, in perpetual despair about their weight and their lot in life. The effect I can have on TV dwarfs anything I can offer in print.

Susie cross-examines me. In a nice way.

“As America’s antidieting guru, Maggie, tell us a little about your own struggle. Was being overweight an issue for you all your life?”

“Well, I got my workouts in the family bakery in Prospect Park, instead of the playground, as a child,” I say, evoking sympathetic smiles from the audience. “I blame my weight problems as a kid on after-school snacks of hot cross buns, crullers and scones instead of carrot sticks and celery. And then, rather than climbing monkey bars and getting real exercise, I rolled dough in my parents’ bakery. Arts and crafts was decorating cookies with colored frosting and rainbow sprinkles, then gobbling up my jewels.”

“Didn’t your parents see what was happening?”

“In those days, feeding your kids was a way of showing you could love and provide.”

“So they were blind to what food had become to you?”

I weigh that for a moment. “Let’s say their gift was disproportionate. When you take a vitamin in the recommended dose, it keeps you healthy. Overdose, and it can be lethal.”

The discussion opens up to the audience, with no time to describe how I continued to overeat as I grew up. In my teens, I got my just desserts—Saturday nights in my room staring at rock-star posters on the walls, and listening to a blaring boom box while entwined in marathon confessional conversations on my pink princess telephone with desperate girlfriends. The secondhand stationary bike that my parents bought me soon became invisible, slipcovered with rejected clothes. If only abandoned exercise equipment could speak.

I was incarcerated in my room under self-imposed house arrest. Everyone else was out on the weekends, at movies, parties or concerts, and I was a prisoner of both my body and the four walls. One night, after going to a dance with my best friend Rhoda, wearing too much makeup and high platform shoes, we ended up in a back booth of Tony’s Pizza parlor at eleven o’clock. There sat Rhoda, black eyeliner melting, sipping Diet Coke and reaching for a third slice of pepperoni pizza. She smirked.

“At least it doesn’t walk away from you.”

It didn’t. Food was the gift that kept on giving.

To make things worse, my parents lightly brushed aside my preoccupation with my weight like crumbs on the counter, seemingly unaware of the pain and disappointment of growing up invisible to boys.

“Just use a little willpower,” my mother would say. “Learn to control yourself.”

Not my sister Kelly’s problem. Like our father, she could eat anything she wanted, and never gain. But I took after my mother. Our bodies followed some Manifest Destiny theory, expanding beyond appropriate borders and nothing could be done about it. Once the fat cells developed during early childhood, the number stayed constant for life. All that diet could do was shrink them down.

“Have you always been at war with your body?” Susie asks after a commercial.

“I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t wending my way through cycles of gorging, deprivation, self-punishment, anger, resentment and rebellion, all of it siphoning off feelings of self-worth.”

Susie turns to the audience for reactions, and a teenage girl in tight jeans with short wavy hair stands.

“I was chubby, as my mom put it, in elementary school and my body made me feel like I was a living sin.” She pauses, taking a breath, then stares into the camera.

“I’m four-nine and I weigh 142 pounds. I feel suffocated, trapped in a dark hole, hopeless.” She looks out beyond the audience. “At first I isolated myself from everybody and all I did was eat, then at the age of thirteen, everything changed.”

“What happened?” Susie asks.

“I became anorexic. I was so paranoid about my unhappiness, I went on for two years being like that. It got to the point where if I had more than thirty calories a day, I would literally hurt myself.” She pushes up the sleeve of a baggy gray sweatshirt to reveal an arm disfigured by the rubbery red scars. “I am a cutter.”

There is stunned silence in the audience. Susie says nothing, as though participating in a moment of respectful observance.

“I know that wasn’t easy,” she says finally. “Thank you.” Thunderous applause rings out, then she turns back to me. “At what point did your thinking change?”

“Staring down at the scale one day. The numbers hadn’t changed and I was ready to smash it to see if that would make it budge. Maybe it was broken. I wanted to pick it up and see, the way you check the phone to see if it’s working when the boy you’re in love with doesn’t call. But then it struck me that there was another option. I could triumph over that meaningless rectangle of steel that I had inveighed with so much of my self-worth by ignoring it and taking back charge of my life. Instead of wallowing in embarrassment and self-hatred, I would take my liability and flaunt it. It was time to fight back against the western world’s prejudice toward a condition that most people couldn’t change. From then on, I refused to dress like a mourner in black to look thinner. I opted for hot pink, chartreuse. I didn’t care if it had horizontal stripes and made my waistline as wide as the equator. I’d go over the top. ‘Too much of a good thing can be wonderful,’ as Mae West said. Diets were a sham, biology was destiny, so I ran with it.”

“What did you do?”

“Aside from shopping sprees in plus-size stores where things actually fit, I turned my attention to my soul. It was time to get in touch with who I really was because everything inside of me that was real and vulnerable had been buried. I started going to Overeaters Anonymous where they began each session by holding hands and saying a prayer: ‘God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can and wisdom to know the difference.’”

“The same prayer that AA uses,” Susie says.

“Yes. And that environment made me realize how much I needed spirituality in my life because I had become so closed off to love and meaning outside of myself. I was turning to a higher power for the love, strength and generosity that I couldn’t find in myself anymore. Until then, I was locked in a one-dimensional life that was consumed with what I weighed and ate, not who I was or could become.”

There are murmurs of agreement from the audience.

“I had lost my place in the universe. Everything in my life was out of proportion.” In the eye of the camera, it all comes back to me. The hot TV lights shine down on me like heavenly beacons there to illuminate the truth, and I’m sweating as if I’m arriving at some religious epiphany. The studio is silent.

“Night after night, I sat in a windowless basement of an East Side church where compulsive eaters shared their stories. One night a withdrawn teenager told of being afraid to fall asleep at night, staying up listening for the sound of her abusive father’s footsteps approaching her room. Strawberry ice-cream sundaes in the kitchen after school were the only thing that made her feel good, and forget his touch, at least for a while.

“A bearded man, very overweight, spoke of atrocities in Vietnam. He had nightmares of seeing the bullet that ripped through his buddy’s chest, and getting there too late to save him. Eating was his escape from the guilt he had over his own survival. Others described stultifying days filled with nursing aging, bedridden parents; facing job loss; empty existence after retirement; the death of a spouse, all tales offering pinholes of light into their intimate worlds of grief and despair. So many people felt orphaned, split off from a world where everyone else seemed to be living purposeful, fulfilling lives.

“Eating filled them all with comfort and satisfaction, but like a euphoric drug, once the high wore off, it left them more despondent than when they started. Watching these people reveal themselves helped me. So did the idea of living life one day at a time, and drawing strength from this community.”

A Clairol commercial prevents me from talking about how science writing connected me to the outside world in a more concrete, expansive way, and how the column and my like-minded thinking with Wharton later propelled me, Maggie O’Leary from Brooklyn, New York, to cult celebrity. Back in the eye of the camera I end by telling viewers:

“Eat to appetite instead of eating to extreme. I’m not saying don’t lose weight if you want to, but I think you should do it without making your life miserable and impossible and unfortunately that’s what very restrictive regimens do. And if you choose to remain at a weight that America deems ‘fat,’ well, that’s okay too if you’re okay with it because in the long run it just might be better than cycling over and over.

“What I hate to see are people subsisting on diet foods that they hate. Food is a source of pleasure, and we should enjoy it. I’m not saying that many of us don’t have terribly serious food issues—it would be disrespectful to be glib about it. There are suicide eaters out there, and they need therapy, not chocolate Kisses.”

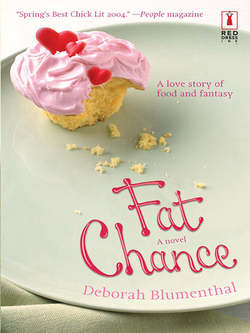

“And, Maggie, let’s talk about your column,” Susie says. “Isn’t ‘Fat Chance’ really a rallying cry for women all over America? Isn’t it really about a lot more than the issue of fat?” As I nod, she goes on.

“Isn’t it about accepting yourself no matter what it is in life that you’re at war with? Isn’t it about giving yourself a break and loving yourself no matter what kind of pressures you perceive that society is putting on you to change, even when those changes may be biologically impossible for you?”

“That’s exactly it, Susie. Fat is something of a metaphor for pain and unhappiness in a world that appears to be filled with people who have it all. The truth is that women everywhere, no matter where they come from, no matter what they do for a living, no matter whether they’re married, or single, rich or poor, famous or utterly anonymous, have issues to deal with and things about themselves that they’d like to change. Ultimately, though, they must come to terms with those issues, because if they can’t or they won’t, they’re destined to be at war with their—”

“And, Maggie—”

But I’m fired up now, and I don’t let her break in.

“And despite liposuction, dieting, exercise, plastic surgery, or what have you, we are a product of our genes and our environments, and the whole business of living the best life that we possibly can means making peace with who we are and overcoming our private saboteurs.”

The audience bursts into applause, and I feel the color in my face rising.

“Thank you, Maggie,” Susie says. “Thank you for being with us today. You’ve brought a very sober perspective to the issues that plague all of us.”

I walk out, surprised with all that I said. A biology teacher of mine once told me that he never really understood his subject until he had to teach it. Now I know what he meant.

Out of the Running

The widespread ill will toward the obese leads to discrimination in schools and the workplace, and reduces chances of women going the old-fashioned route and climbing the social ladder through marriage.

When was the last time a society column pictured a fat woman at a social event? Or sitting on the board of a major corporation?

Undoubtedly, being overweight sabotages success. Ninety-seven million of us are overweight, but when it comes to fame, celebrity, recognition and status, we are invisible.

Over and over again, I hear about discrimination at the office—how women are passed over for promotions. Some are too embarrassed to sue, unable to handle the attention that would put them in the spotlight. Instead, they endure lower-level jobs, less pay and the anger that comes from being victimized and unable or unwilling to fight back.

But should you have the courage to stand up and fight back, the sad truth is that juries often show the same lack of sympathy toward the overweight that is mirrored in the real world. Out of the entire United States, only Michigan, Washington, D.C., San Francisco and Santa Cruz, California, make it illegal to discriminate against the overweight. Every place else, society is largely off the hook. The rationale: If you’re fat, it’s your own fault.

And here’s the saddest evidence yet of how much society despises overweight. In a national survey done by Dorothy C. Wertz, an ethicist and sociologist at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, 16 percent of the general adult population said they would abort a child if they found out that it would be untreatably obese. By comparison, the survey found that 17 percent would abort if the child would be mildly retarded.