Читать книгу No Ordinary Heroes: - Demaree Inglese - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 6

ОглавлениеEvening:

The National Hurricane Center warns that Katrina is “potentially catastrophic,” and the levees may be “overtopped.”

Some 36,000 evacuees crowd into the Superdome.

Mayor Nagin orders a 6 p.m. curfew.

The sight of so many people waiting to get into the Superdome had a sobering effect on Gary and me, and we both tried to hide our uneasiness as we unloaded the patrol car in front of the Correctional Center.

“We’ll have to make three trips, maybe four.” Gary stared at the stuff piled in the trunk and picked up a carton of bottled water.

“We have all night.” I lifted two boxes of food and led the way up the two dozen front steps.

“This water is really heavy,” Gary said, panting when we reached the wide porch that surrounded the building. The first floor was twenty feet smaller than the nine stories above, and large cement columns supported the upper stories, creating an overhang that formed a ceiling for the porch.

“Don’t complain. It’s good exercise.” I halted as two grade school boys ran past me, laughing and shrieking. When an elderly man walked around the corner, the boys stopped to pet his small dog.

Here we go again, I thought. Every time we had a hurricane alert the deputies brought spouses, children, or parents to shelter at the jail. That was understandable; unlike most houses in New Orleans, these buildings were made to withstand the weather. But the thought of all those civilians made me uncomfortable. I worried for their safety. I didn’t like the idea of inmates sleeping in such close proximity to children and their animals. Cats in cages were bad enough, but some of the families even brought pet rabbits!

It looked like fifty to a hundred people had already arrived. They would probably number close to two hundred in the end, and if the storm was as bad as predicted, we might have some neighborhood residents, too, before long. Several people gathered on the porch, watching and waiting as they did before every storm.

Inside, civilians and their belongings crowded the lobby. It looked like a flea market free-for-all with grocery bags, cases of water, suitcases, electronic gear, toys, pet carriers, and bedding stashed along the walls. People of all ages sat on the fixed plastic chairs where family members waited to see inmates on visiting days. Kids and teenagers sprawled on the floor. They played cards and board games, listened to radios, or just talked. For many, conversation and laughter were ways to take one’s mind off the storm.

Gary followed me across the lobby and through a metal detector to the elevator. We had too much to carry up the stairs. When the elevator door opened on 2, I was surprised to see people sitting on the floor of the large foyer. They were sorting through supplies, arranging pillows and blankets, and plugging TVs and game systems they had brought from home into whatever outlets they could find.

The hubbub of noise and activity was muted when we entered the door to Medical Administration. I put the food on a chair in my office, while Gary stashed the water in the cramped filing room down the hall.

“Hey, look who’s here.” Mike stood by his office. The psychiatrist had piled boxes in the open doorway to keep his dogs inside. One of the animals barked. “I bet Dem just can’t wait to give you boys a big hug.”

“Let’s skip the hug.” I glanced over the barrier. As long as I didn’t get too close, my eyes wouldn’t start watering. Moby, a black-and-auburn English bulldog, was short and solid with a squashed face. The bearded collie, Georgie, resembled a small sheepdog, taller with long gray-and-white hair. They were making themselves right at home.

“Maybe it’s a good thing you brought them,” I said. “If the storm is as bad as they say, we can always eat them.”

“I’d sooner eat you,” Mike replied indignantly.

“In fact, we should change their names. Let’s call them Lunch and Dinner.” I loved to bait Mike.

He rolled his eyes. Mike enjoyed verbal sparring with his friends, and he could take it as well as he could dish it out. Neither of us missed a chance to zing the other.

Paul called out from Mike’s office, ready as always to pass along the latest warnings and bulletins. “The mayor just set a six p.m. curfew. There’s almost no chance Katrina will miss us.”

He and Brady were glued to a television on Mike’s desk. We hadn’t used the TV since 9/11, when we were all riveted to the news coverage. Now the set was tuned to the Weather Channel.

Gary and I made a few more trips to finish unloading the patrol car, then I drove it to a raised parking lot two blocks away and jogged back in steadily falling rain. But the wind wasn’t bad, and I didn’t even bother to change my damp clothes when I returned to Medical Administration.

The mood there was surprisingly light. None of us had actually been through a hurricane of significant size before. Despite numerous threats, previous storms had all veered off at the last minute to wreak their havoc somewhere else. Even now we still had a hard time accepting that Katrina would be different, though the predictions of 160-mile-an-hour winds and double-digit storm surges pouring out of the radio and TV were starting to grate on me.

Dire forecasts aside, we talked and joked while we inventoried our supplies. I looked around the group. If someone didn’t know us, I had to admit it might be hard to tell us apart. All of us were white, with short dark hair, predominantly in our thirties, mostly ex-military, and in good physical shape. But when it came to personalities, our differences emerged.

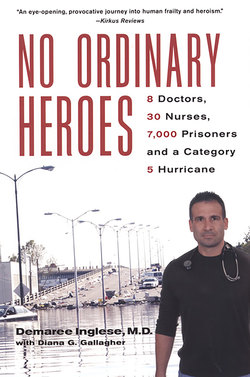

I was the extrovert, perhaps due in part to the same Italian heritage that accounted for my Roman nose and my last name, Inglese. My nickname, Dem, was short for my middle name, Demaree, the result of a whimsical impulse on my parents’ part.

Mike, a clean freak, was almost obsessive about what he ate. He opened a large tub of low-fat bagel chips, took a handful, and passed the container. Then he pulled low-fat crackers and no-added-sugar peanut butter out of a grocery bag.

“Do you ever eat anything that’s not low-fat?” Paul asked.

“Ha!” Brady laughed heartily. “He even brought low-fat dog food for Moby and Georgie.”

Gary grinned. “Are you sure you want to go on The Amazing Race with this guy, Dem?”

Every Tuesday, Mike, Gary, and I got together to watch the reality TV show that pitted teams in round-the-world competitions that were part treasure hunt and part Fear Factor. When the call went out for contestants for the upcoming season, Mike and I had dressed in scrubs and recorded an audition video inside a jail cell. We thought our comical introduction and clever repartee—and the fact that the show had never featured physicians, let alone jail employees—might do the trick. We hadn’t heard back…yet.

“Looks like we have plenty of food.” Gary closed the cooler he had brought and pushed it aside.

“And water,” Brady added.

Among us, we had nearly twenty gallons. Paul had found more bottled water and a half-case of Gatorade in the file room. That would be more than enough. Once the storm had passed over, we expected to be back at home within a few days, back to normal.

“Did everyone bring batteries?” Paul asked.

We all had some, mostly Ds for flashlights.

After we finished our inventory, I went into my office. In spite of the mounting tension, the calm professional in me took over the moment I sat at my desk. I picked up the phone to check in with the physicians at Intake and Templeman. At the infirmary in Templeman 1, Victor Tuckler, a moonlighting ER physician from Charity Hospital, had reported an hour early for his 7 p.m.–to–7 a.m. shift.

“Landfall at dawn,” Paul announced, sticking his head in my doorway for a second before ducking back out. We could expect Katrina to come ashore in less than twelve hours.

Victor might be staying longer than usual tomorrow, I thought, but, with 7000 inmates to care for, I could use the extra help. Templeman 1 and 2 housed 1,500 general population inmates, along with the 200 seriously ill infirmary patients. During the emergency, Sam and Victor could look after them all.

Gary and I could handle the 800 inmates housed at the Correctional Center. Some were immigration detainees who spoke only Spanish, but Gary was fluent. He had spent two years as a Mormon missionary in the Dominican Republic.

Mike came in and perched on the edge of my desk. “Dr. Shantha brought her son, Vinnie, here on her way to the Psych Unit in the House of Detention. He’s staying in an office on the second floor, near the guys in the Communications office.”

I nodded approval. Vinnie was nineteen, and he’d be more comfortable with us than at the building where his mother had charge of the jail’s most serious mental patients, psychotic inmates and patients with suicidal and homicidal tendencies.

Paul appeared in the doorway again. “The clinic nurses are putting together a week’s worth of pills for the inmates who’re on medications. If we lose power or have a problem, the patients will be set.”

Brady barged in past Paul. “Sam just called wanting more IV fluids for the infirmary. I’ll take what he needs from Medical Supply and bring some to the other clinics, too.”

“Wait a minute.” Paul left without explanation and immediately returned with a dozen handheld yellow radios. He looked at Brady. “I got a bunch of these from the warehouse and was just getting ready to pass them out. Can you take them to the clinics? Then we can talk to each other if the phones go down.”

After everyone left, I concentrated on my paperwork, including the case review of Carl Davis’s death. The paper records on my desk had gone limp in the oppressive humidity, a side effect of the faulty second-floor air-conditioning. Water stains marred the ceiling, and paint was peeling off the wall. Every building in the jail—all of them steel and cinderblock structures—showed signs of age; the Correctional Center had leaky plumbing, too. Despite the dismal decor, I had never regretted my decision to become medical director. The past six years had brought satisfaction that far exceeded the difficulties.

We’d improved the health care tremendously, adding laboratory services, treadmill testing, and X-ray imaging to the clinics. In addition we had increased the numbers of doctors and nurses, hiring well-qualified full-time providers, despite the lack of recognition, poor salaries, and less than appreciative patients…dangerous patients.

Of course, we’d never actually had to face a hurricane like Katrina. Whatever lay in store, we’d have to deal with it. My office was quiet, and putting aside thoughts of inmates, sheltering civilians, and possible emergencies, I turned my attention back to the medical records. I wanted to finish them before dinner.