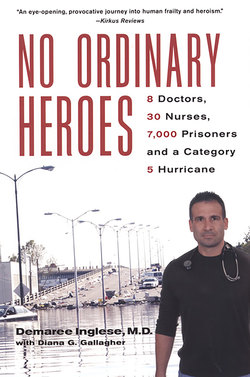

Читать книгу No Ordinary Heroes: - Demaree Inglese - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 1

ОглавлениеMorning:

Hurricane Katrina is declared a category 5 storm, with winds at 160 mph.

The eye is still 250 miles from the mouth of the Mississippi River.

The Superdome opens as a shelter at 8 a.m.

At 10 a.m. Mayor Ray Nagin orders a mandatory evacuation of New Orleans.

“He died?” I coughed to clear my throat. The phone call from the jail had awakened me from a deep sleep, and my thoughts were fuzzy. No wonder, I realized with a glance at the clock on my bedside table. It was 6:54 a.m. After a Saturday-night foray to a club on Bourbon Street, I had slept less than four hours.

“Yes, Dr. Inglese,” a deputy sheriff said. “At Charity Hospital, half an hour ago.”

“I’ll be right there.” I groaned when he hung up. Next-of-kin notification was one of my more unpleasant duties as the head physician at the New Orleans jail.

Swinging my legs off the bed, I rubbed my eyes. Carl Davis, a violent repeat offender with advanced cirrhosis, had spent the past two and a half years in the jail infirmary, and though my medical staff worked hard to give all our inmates excellent care, his death had been inevitable.

A hot shower washed away the remnants of Bourbon Street dirt and smoke, and I checked a mirror. My close-cropped hair needed barely any attention, but beneath my dark, thick eyebrows, my eyes kept trying to close. The stubble on my square jaw could stay. I hated to shave.

By the time I put on green scrubs and went to the kitchen, I was almost awake. Except for a few packets of instant grits, my cupboards and refrigerator held few promising prospects for breakfast. My house had just gone on the market, and the realtor was starting to show it. I didn’t have the time or patience to clean the kitchen on a moment’s notice.

It wasn’t that I wanted to leave town. I had put a lot of time and effort into this house. A hundred years old, near Tulane University, it had hardwood floors, ceiling medallions, elaborate moldings, a veranda, a slate courtyard, gardens—all the elegant charm of historic New Orleans, plus two newly renovated floors, the result of hours of my free time over the past eighteen months. But I no longer wanted to spend my weekends and evenings working in the yard or making repairs. A condo was much more practical for a thirty-nine-year-old single man with two jobs and an active social life, and I eagerly wanted to move into a new place I’d found on the river.

The condo, close to the gym where I worked out almost every day, was also near my favorite restaurants and the park where I ran—and a quick ten minutes to my haunts in the French Quarter. And it didn’t hurt that the condo provided an excellent view of the Mardi Gras parades. When it came to being a doctor, I took my work seriously, but I also loved New Orleans and its lively party scene.

I wolfed down a bowl of grits and listened to the latest weather report. Tracking the progress of Hurricane Katrina had engrossed the entire city over the past few days. But because New Orleans had a two-decade history of bad storms swerving away at the last moment, most residents retained a devil-may-care attitude that was at odds with the increasingly serious predictions and the hurricane’s current path. Despite the morning’s sun, Katrina was still bearing down on New Orleans, and it had just been upgraded to a category 5—potentially catastrophic.

It was only about three miles and a ten-minute ride to my office at the Community Correctional Center. But I hadn’t bothered to fill up my Mercedes yesterday, foolishly assuming I’d have all day today to do that. Instead, I took the patrol car I used for official business, but its gas gauge, too, hovered near empty. Procrastination was one of my bad habits. Though I made sure everything at the jail ran like clockwork, I tended to put off mundane personal tasks, like paying house bills and filling gas tanks.

As I drove down the oak-lined roads of my uptown neighborhood, I was struck by how deserted it was. No one was out on the porches that wrapped around the gracious Victorian homes. The boisterous Tulane students who normally clustered on the streets were absent. Even more worrisome, every gas station I passed was closed and boarded up.

I caught a glimpse of the Broad Street pumping station, which kept below-sea-level New Orleans dry in ordinary weather. Katrina would undoubtedly give those pumps a real workout over the next few days.

A twinge of panic pierced my fatigue. I couldn’t have known an inmate would die, but I was beginning to regret going out last night. A more prudent man would have gotten gas and gone shopping instead. Too late now, I thought, as I turned onto Tulane Avenue, a main city thoroughfare, which led right past the jail complex. Notifying Carl Davis’s next of kin and preparing the necessary reports had priority over gas and hurricane supplies.

Since Davis had died of natural causes, telling his family might be easier than when I had to explain an unexpected or violent death. He had cirrhosis of the liver, an incurable disease, and the inmate’s condition had deteriorated steadily despite aggressive medical treatment. That didn’t mean, however, the family would take the news calmly. After six years at the jail, I hadn’t been able to alter the public misconception that inmates were given inadequate care. That belief was too entrenched to dislodge.

Maybe the hurricane would keep the story off the front page, though. Newspapers and television routinely presented a skewed account when reporting the death of an inmate, ignoring critical facts that exonerated the medical staff. The New Orleans jail booked 105,000 arrestees per year and averaged only eight deaths, one-third the national average. The low death rate was even more impressive considering the nature of our jail’s population. Most of the inmates came from an impoverished, drug-using, inner-city environment, and almost all had medical problems: 5 percent had HIV, 20 percent latent tuberculosis, and 29 percent hepatitis. A quarter of the inmates suffered from mental illness, and 70 percent had drugs in their blood at the time of booking. The homeless and indigent lacked primary care, and some deliberately committed minor crimes to get access to the jail’s medical services.

I was proud of what we’d accomplished. In 2000, Charles C. Foti Jr., the sheriff of Orleans Parish for thirty years—later Louisiana’s attorney general—had hired me to reorganize and improve the jail’s medical department. I instituted many new programs, including screening and treating inmates for communicable diseases, which significantly curtailed the spread of infections throughout the city. Just last September, in 2004, the National Commission on Correctional Health Care had recognized the jail for providing outstanding medical care at a low cost. Unfortunately, most of the public hadn’t noticed.

Bad publicity plunged to the bottom of my things-to-worry-about list as I parked across the street from the Correctional Center’s glass-fronted entrance. Its towering ten stories underscored the building’s importance as the command center for the thirteen buildings that made up the jail. Slamming the car door, I ran up the front steps and took the elevator to Medical Administration on the second floor.

Paul Thomas, the director of nursing, stepped out of his office as I walked through the door. “What are you doing here so early?”

“Carl Davis died at Charity Hospital an hour ago.” I walked past the bathroom and into my office, one of seven spartan rooms that opened off the center hallway. Fluorescent lights lit the corridor, which ended at a small barred window. My office was like most of the others: a computer stood on a cheap pressed-wood desk that took up much of the stained tile floor.

“Like you don’t have enough to do today.” Paul paused, his burly frame filling my doorway.

“I have to notify Davis’s family before I do anything else.” I sank into my desk chair and looked up. “Did the mayor order a mandatory evacuation?”

“Not yet, but he will,” Paul said. The soft-spoken fifty-two-year-old was the department hurricane fanatic and de facto alarmist. Whenever a tropical depression was upgraded and named, tracking charts went up on his office wall. He logged on to weather websites, made meticulous contingency plans, and kept everyone in Medical Administration advised of course changes and projections. The downside of Paul’s obsession was his insistence that every new storm would be the one to finally ravage New Orleans.

“I decided to bring the nurses in at three instead of six,” he said. “If we don’t get everyone here early, some of them might not show. This storm’s a bad one, and people are starting to panic.”

The gravity of the approaching storm made my windowless cinderblock office seem smaller and more cramped than usual. I called a deputy in the Communications Division, which relayed calls and information throughout the jail complex, then talked to someone in the Special Investigation Division. SID deputies handled the detective functions of the sheriff’s office, and they were already looking for Carl Davis’s next-of-kin.

I began collecting all the records pertaining to his illness, treatment, and death, including a download from Charity Hospital. The massive, free-care medical center stood a mile and a half down Tulane Avenue past the courthouse. Staffed by the Schools of Medicine at Tulane and LSU, the facility was a Level 1 trauma center. That was where we sent inmates who were too sick to be cared for in the jail’s infirmary.

As the hospital record printed out, I called the infirmary, where Davis had been housed. Every inmate had a medical chart, containing doctor’s notes, X-rays, lab results, and medication records. I would need the complete file to conduct a thorough case review. Two hours later—with periodic interruptions by Paul to let me know of Katrina’s worsening outlook—I had all the necessary paperwork on Davis, but SID had still not located any family member. Assuming they had evacuated, we postponed the notification until after the hurricane.

On my way out of the building, I ran into Captain Allen Verret, the associate warden of the Correctional Center. A barrel-chested man of forty-three, with a mustache and brown hair flecked with gray, he had the calm, assured presence of a born leader. He instilled confidence and treated his deputies with the same respect they felt for him.

“How’s it going?” I asked. The Correctional Center warden—each building in the jail complex had its own—was away on vacation, and Verret was in charge.

“It’s been a busy couple of days. I barely had enough time to see my wife and son off to Mississippi and pack a bag for myself.” Verret’s manner was off-hand, but deep worry lines creased his face. He was obviously preoccupied with serious matters.

“I don’t really believe all this,” I confessed.

“You’re not the only one,” Verret said. “I just came from a meeting with the sheriff and his officers.”

Verret told me he and several others had voiced serious reservations about keeping the inmates at the jail. I had raised similar concerns myself yesterday, and I certainly wouldn’t have been shy about arguing had I been invited to the meeting. I could be insistent and even headstrong when pressed.

But now that Jail Administration was certain that Katrina would hit, they felt there was no longer time to evacuate almost 7,000 prisoners. In addition to the usual 6,400 inmates, the facility had taken in 374 prisoners from neighboring St. Bernard Parish, which was considered more likely to flood.

“We don’t have enough food, water, flashlights, and batteries stored in the warehouse,” Verret continued. “If we’re here longer than a couple of days…”

“We’re as prepared as possible in Medical,” I assured him. We’d been implementing our disaster plans for a couple of days. “The clinics have been stocked with supplies, and the nurses will pass out extra meds just in case.”

“Good.” Verret nodded. “Jim Beach wanted to distribute food and water to all the buildings before the storm, but Administration decided to wait.”

As the director of Food Services, Major Jim Beach was responsible for providing 20,000 meals a day to the prisoners. On a routine day, three cooks and two dozen inmate workers prepared breakfast, lunch, and dinner in the kitchen, then transported the food—one hot meal and two cold ones daily—to each of the jail buildings, where deputies and inmates carried it to the tiers, as the barracks-like cells were known. The hurricane would undoubtedly create problems, and Beach was trying to anticipate them.

As I left Verret and walked outside, Paul Thomas’s latest bulletin weighed on my mind: “The Mayor just ordered a mandatory evacuation of the city. This is going to be brutal.”

Katrina was the worst storm to threaten the Louisiana coast in recorded history. There was nothing more I could do to prepare at the jail, and I still had to gas up two cars, buy food and water, and pack.