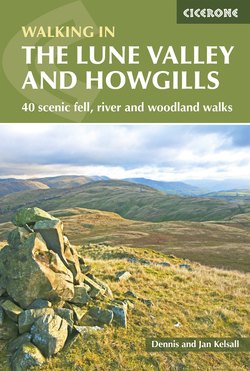

Читать книгу The Lune Valley and Howgills - Dennis Kelsall - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеWALK 2

Newbiggin-on-Lune

| Start | Ravenstonedale (NY 722 042) |

| Distance | 6½ miles (10.5km) |

| Time | 3hr |

| Terrain | Field paths and disused railway |

| Height gain | 240m (787ft) |

| Maps | Explorer OL19 – Howgill Fells and Upper Eden Valley |

| Refreshments | Black Swan at Ravenstonedale, Lune Spring Garden Centre café in Newbiggin-on-Lune |

| Toilets | None |

| Parking | Parking in front of St Oswald’s Church |

This walk straddles the subtle watershed between Lunesdale and neighbouring Smardale, where Scandal Beck is one of the principal tributaries of the Eden, a northerly flowing river that enters the Solway Firth below Carlisle. The country here is underlain by limestone, its pale grey countenance reflected in the farm buildings, cottages and dry-stone walls that enclose the fields, but brightened in spring and summer by the flowers that abound in the hedgerows and banks. Beginning in Ravenstonedale, the walk crosses the fields to Newbiggin, where a spring is traditionally held to be the source of the Lune. Following the course of a former railway into the pretty valley of Smardale, it returns to the village past medieval earthworks.

ST OSWALD’S CHURCH, RAVENSTONEDALE

Ravenstonedale’s churchyard is home to the village’s most ancient monument, the base of a Saxon cross, indicating the existence of Christian settlement well before the arrival of the Normans. Towards the end of the 12th century, the manor was gifted to the Gilbertine priory at Watton in Yorkshire, part of the only religious order to have been founded by an Englishman.

The son of a Norman knight and born at Sempringham in Lincolnshire, Gilbert died in 1189, having lived to be over 100. He was revered for his piety and his work with women and the poor, and over 30 houses were established in his name, although the priory at Ravenstonedale is the only one known west of the Pennines.

The ruins, which lie beside the church, date from around 1200 and once housed a small community of canons and lay brethren. Little remains apart from the excavated foundations, and it is likely that when St Oswald’s Church was rebuilt in 1744 the ruins were plundered as a convenient quarry of ready-cut stone.

A splendid building from the outside, the church is even more remarkable within, being one of few in the country that adopt the collegiate plan, where the pews face inward to a centre aisle. The most spectacular feature is undoubtedly the grand three-decker pulpit, rendered even more imposing by a massive sounding-board suspended above. It came from the earlier building and commands the attention of all.

The interior layout of St Oswald’s, unusually, is based on the collegiate plan

From the front of St Oswald’sChurch, head into the village, following the lane signed to Sedbergh. At a junction by the Black Swan, turn right and then, at the next junction, fork right past a raised green. At the end, go right again to Town Head Farm. Bear left through a gate to pass beside cattle sheds and then bend left along a short walled track into a field. Strike a right diagonal to the far corner and head down to a bridge spanning the usually dry bed of Scandal Beck. A few steps beyond, watch for a squeeze-stile in the wall above. Walk out to the corner and continue up the next field.

At the top, go left through a gate and follow the boundary away. To the south, beyond Greenside Tarn, the northern slopes of the Howgills rise to Green Bell, from whose flank springs Dale Gill, the Lune’s most distant tributary from the sea. At a protruding stub of wall, part-way along the second field, swing right through a squeeze-gap towards a cottage. Wind left and right out of the fields onto a narrow lane.

Follow it left for ¼ mile (400m), leaving after the second cattle-grid for a stile on the right. Pass behind High Greenside Farm, crossing a succession of fences to a wall-stile at its far side. Over that go right above Greenside Beck. Entering the third field by a barn, turn left to a bridge spanning the stream and leave the pasture along a drive from a cottage. Newbiggin-on-Lune is signed right beside the stream past a well-preserved lime kiln.

The 18th century was an age of agricultural improvements, which included the use of lime as a fertiliser. Thousands of field kilns were built up and down the country, in which limestone was burned using culm, a poor quality coal, as a fuel. The process took a couple of days, after which the quicklime was raked out and left to weather before being laboriously spread over the fields to counteract acidity in the soil.

At Beckstones Farm, cross a bridge to the other bank, but where the track then shortly swings right, keep ahead on a narrow path into thicket. Parting company with the stream, mount a stile and walk the length of a field to meet a lane at the edge of Newbiggin-on-Lune. Head towards the village, but go right at the first junction to reach the main road beside the Lune Spring Garden Centre. Taking the narrow lane diagonally opposite, look over the left wall to see a grass mound, the site of St Helen’s Chapel, and a stream that upwells beside it, the River Lune. A stile a little further along gives access to the field.

The perpetual spring of St Helen’s Well was probably revered long before the arrival of Christianity and, as was often the case, adopted by the new religion with the foundation of a chapel. The resurgence has traditionally been regarded as the true source of the Lune, a Celtic name meaning ‘pure’ or ‘healthy’. St Helen was the mother of Constantine I, the first Roman emperor to embrace Christianity, and she was credited with discovering the ’true cross’ on which Christ was crucified.

Cross the field, through which runs a second stream, to a track at the far side and follow it right beneath a disused railway bridge to a junction at the entrance to Brownber Hall. Turn right again, the way signed to Smardale. Winding past a barn, meet the course of the Stainmore Railway, which ran across the Pennines between Tebay and Darlington. Join the former railway through a gate on the left, shortly passing the ruin of Sandy Bank signal box, which marked the summit separating Lunesdale and Smardale. The line runs on into a cutting, the banks resplendent in spring with wood anemone, celandine, coltsfoot, primrose, cowslip and violet. After passing beneath a bridge, its parapet still blackened by soot, the track winds past an abandoned limestone quarry and kilns before curving across an impressive viaduct straddling the gorge.

The Smardale Gill Viaduct is an impressive example of Victorian engineering

SMARDALE QUARRY AND SMARDALE GILL VIADUCT

The quarry opened shortly after the Stainmore Railway in 1861, providing stone for the massive lime kilns that were built beside the track. The unprecedented industrial expansion and urbanisation of the 19th century created a huge demand for burnt lime, since it was used not only for fertiliser but also for mortar and cement and in the production of glass and the smelting of iron. The lime here was destined for the steelworks at Barrow and Darlington, but the quality proved inferior, and the quarry was abandoned before the end of the 19th century.

The viaduct, a little further along, was an impressive demonstration of Victorian engineering, its 14 arches spanning 168m and carrying the track 27m above the river. It was built with the foresight to accommodate twin lines as traffic increased, but although much of the route was soon upgraded to two-way operation, the section here remained single track. With the closure of the Barrow steelworks in 1961, the line was shut and the rails removed, along with several viaducts, including that across the River Belah, which lay 9 miles (14.5km) to the east. At 60m high, it was the tallest bridge in Britain. The Smardale Gill Viaduct almost shared the same fate, for by 1980 its condition had deteriorated to the point of becoming dangerous. However, British Rail offered a grant reflecting the cost of demolition for its restoration, and the bridge was re-opened in 1992 as a link to the Smardale Nature Reserve along the valley.

On the far side of the viaduct leave over a stile on the right, from which a path runs back up the valley, giving a superb retrospective view to the viaduct. After passing the limestone quarries over on the other side, watch for a fork and climb to a stile above. Those with their noses to the ground will have noticed the rock underfoot change from limestone to sandstone, which was cut from the hillside a little further along for the construction of the viaduct. Beyond the quarries, cross a stile and follow a bridleway down to Smardale Bridge.

Climb away to a stile a short distance up on the left and head out across the hillside to meet a low earthen dyke. It was part of a boundary enclosing the valley and was raised by monks from the small Gilbertine priory at Ravenstonedale to protect their timber and fishing rights. The hillside terraces above are lynchets, which were created by medieval strip ploughing. Follow the dyke past the end of a stand of timber above a narrowing of the gorge. Later, the path loses height across an open field, where low grass pillow-mounds are the remains of conies or warrens, built during the Middle Ages to encourage breeding rabbits to provide a ready source of meat. At the far end, posts mark the path down a steep bank to a footbridge across a side-stream from Hag Mire.

Walk up to join a rising track towards Park House, but after 100m branch down beside a fence. Through gates, cross a second track coming from a bridge and carry on past a byre beside the river. Through a gate on the right by a footbridge join the adjacent track and follow it beneath the road bridge into Ravenstonedale. Reaching the main lane, cross Coldbeck Bridge, and at the junction immediately beyond bear right between buildings, from which a path leads across a playing field back to St Oswald’s Church.