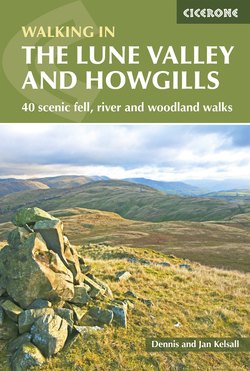

Читать книгу The Lune Valley and Howgills - Dennis Kelsall - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Looking back past the Lune Viaduct towards Arant Haw (Walk 14)

The area of the Lune valley, nestled between the Lake District and the Yorkshire Dales, begs discovery and presents no shortage of inviting walks to suit every taste and inclination. The selection of walks in this guide reveals its many facets, with routes that clamber onto the hills overlooking the main valley, delve into the tributary dales that feed it, or simply follow the River Lune itself. Further downstream the routes wander the two promontories between which the Lune finally meets the sea near Lancaster, seeking out the many picturesque and interesting corners there. In some walks, aspects of the area’s rich history are revealed, while few rambles lack opportunities to observe wildlife at any time of year. Walking is one of the best forms of physical exercise, and in a setting such as this, it cannot help but be good for the mind and soul too.

Although it gives its name to Lancashire, the River Lune is born in what was Westmorland, a historic county that was swallowed up within Cumbria during the reorganisation of local government in 1974. The river’s higher reaches fall from the Howgill Fells in a fold that separates the western dales of Yorkshire from the rolling hills of south-east Lakeland. The river enters Lancashire only below Kirkby Lonsdale, but immediately encounters some of the county’s prettiest countryside. Lower down it skirts the Forest of Bowland before passing through Lancaster to find eventual release into Morecambe Bay and the Irish Sea.

Although surrounded by hills, it is the Howgill Fells to which the Lune is most intimately related, that distinctive massif of high ground rising dramatically to the east of the M6 as it passes through the deep trough of the Lune Gorge. The tentacles of the river’s upper tributaries completely encircle this compact group and effectively set it apart from the neighbouring Pennine and Lakeland hills.

The Lune is a relatively short river, yet it embraces a considerable upland sweep that includes The Calf and all the other high tops of the Howgills, a corner of the Shap Fells, as well as the southern aspect of Great Asby Scar. Further south, Whernside and most of Ingleborough also lie within its reach, the catchment curving around to include the northern slopes of the Forest of Bowland. But the area explored within this book is not confined to the high hills, and there is much of interest too within the main valley and its tributaries. Borrowdale, Dentdale and the secluded valleys of Bowland are particularly beautiful, while the estuarine marshes and coast reveal other aspects of the area’s character.

Beached boats indicate that the high tide covers the salt marsh (Walk 40)

Besides Lancaster, Kirkby Lonsdale and Sedbergh are the only towns situated by the river, and the area is largely untouched by conurbation or industry. The beckoning landscape ranges from the untamed, expansive moorlands of the high tops to secluded woods, bucolic countryside and tide-washed coast, all combining to offer walking that is both varied and rewarding. Although there are undoubtedly challenges to be found, none of the routes included here is overly demanding. They focus upon walking for enjoyment to appreciate the scenery, wildlife and plants encountered while the text also offers background to some of the features and curiosities passed along the way.

Traditionally, the river is regarded as upwelling from the ground beside the mound of an ancient chapel dedicated to St Helen in the hamlet of Newbiggin-on-Lune, although higher and longer tributaries complicate any discussion of its source. The river’s 50-odd mile journey to the coast winds almost entirely through unspoiled countryside, and along its length the river subtly exchanges the wild scenery of rolling, deserted moorland hills for a more intimate pastoral setting of waterside meadows and woodland.

Scattered throughout the upper Lune Valley are attractive farmsteads, hamlets and villages, with only two settlements large enough to claim the status of town, Kirkby Lonsdale and Sedbergh (the latter being set back a couple of miles from the main flow). Both ancient market centres, they retain a delightful individuality that is becoming increasingly hard to find in today’s towns. They make ideal bases for a few days’ exploration of the area or convenient stopping-off points for those wishing to create an ’end-to-end’ trek along the valley.

The only major conurbation within the river’s entire catchment is Lancaster, founded by the Romans as a garrisoned port at the river’s lowest bridging point. Throughout the Middle Ages the County Palatine of Lancaster was governed from its intimidating medieval castle and, although the county’s administrative centre has now shifted south to Preston, Lancaster is still considered the county town. During the 18th century it rivalled Liverpool as a great seaport, trading with the Baltic States, Africa and the Americas, but with a silting estuary and shifting centres of economic activity, Lancaster’s maritime importance faded into history. Downstream, the city is quickly left behind and the river, tidal from this point, winds to a lonely estuary across an expanse of largely empty coastal plain, where extensive salt marsh and mud flats attract a host of birds to feed at low water.

The landscape through which the river flows boasts great beauty and diversity, yet much of the main valley, let alone its many tributary dales, is relatively unknown and little visited, overshadowed by the proximity of more well-publicised neighbours. Few of those passing through to the Lake District, the Yorkshire Dales or points further north afford it little more than a passing glance and most are largely oblivious to the loveliness of its uncluttered countryside. The Howgill Fells and the Forest of Bowland are among the country’s least frequented hills, and few but locals are aware of the attractive hamlets and villages scattered along the length of the valley.

Looking back to Beckside from the path to Harprigg (Walk 19)

The rewards of such relative obscurity are found in unfrequented hills and vales, an absence of the trappings of commercialism, and a freedom from the obligation to undertake a handful of ’must do’ routes. In and around the Lune there are no ’highest peaks’ to climb or ’longest ridges’ to traverse, and the one or two spots that have gained a justified popularity have yet to succumb to over-exploitation. Travelling from one end of the valley to the other reveals an ever-changing scene that is constantly and subtly altering to offer something uniquely special.

Much of the upland catchment is open-access land where walkers can roam at will, while miles of paths, trackways and quiet lanes offer endless scope for inquisitive and uncrowded explorations. The revelation of far-reaching views from the tops contrasts with the intimacy of secluded woodlands and deep, winding valleys, while the abundance of plant and wildlife and endless wayside curiosities more than matches that to be found along the well-worn trails of the more popular haunts.

Across the Lune Valley from the top of Firbank (Walk 14)

Origins and landscape

The waters of the Lune

Identifying the origin of any river depends upon the rules by which you want to play – highest point, longest course, farthest from the sea and so on. An unambiguous answer is rare, and the River Lune is no exception.

The first reference to its name on the map is the hamlet of Newbiggin-on-Lune, where the river is held to bubble up from the ancient and holy perennial spring of St Helen’s Well. Other authorities point out that the stream below the village is called Sandwath Beck, and only beyond its confluence with Weasdale Beck, a mile downstream at Wath, does it become the Lune. Yet by the time its reaches Newbiggin, Sandwath Beck is already into its third name, having started life out as Dale Gill and then become Greenside Beck. Up the hill behind Newbiggin, Dale Gill issues from a couple of uncertain springs, just below the summit of Green Bell, and it is from here that longest meandering course to the sea can be traced.

Built in the 18th century, Smardale Bridge straddles Scandal Beck (Walk 2)

However, the consideration of height adds yet another factor to the debate. Without doubt, at 723m Ingleborough is the river’s most lofty source, although any rain falling on the summit is immediately sucked into the labyrinth of fissures, pots and caves beneath the mountain and only reappears much lower down its flanks. The beginning of the highest continuous stream is a shallow tarn at around 665m on the summit of Baugh Fell, from which flows the River Rawthey. Perhaps the only way to be certain of having dipped your toe in the river’s source is to visit all five locations.

Whatever its beginnings, the River Lune has a catchment extending over 430 square miles (1114km2), but it is peculiarly one-sided in that, for much of its length, the western watershed is less than two miles from the river, so all major input is from the east. The only significant streams that contradict this lopsidedness are Birk Beck and Borrowdale, which fall from the Shap Fells on the fringe of the Lake District National Park, and Chapel Beck and Raise Beck, springs seeping from the limestone of Great Asby Scar, which overlooks the budding river from the north. The Lune’s infant tendrils almost completely encircle the Howgill massif, with only a couple of streams that feed Scandal Beck escaping capture to flow northwards into the River Eden. Further south the Lune’s tributaries penetrate deep into the western dales of North Yorkshire, stealing all the rills and rivulets from Baugh Fell, Whernside and the majority of those from Ingleborough too. Even in its final stages, the Lune maintains its intimacy with the high hills, for the northern slopes of the Bowland fells also come within its grasp.

Landscape

While the Lune catchment lacks the unified identity that designation as a national park or AONB creates, it impinges upon the existing national parks of the Lake District and Yorkshire Dales, as well as the Forest of Bowland Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. Since the national park boundary changes of 2016, virtually all the catchment north of Kirkby Lonsdale now lies within one or other of the national parks and is a formal recognition of its special qualities. The catchment compares well with both the scale and character of such designated areas in Britain, for although only half the size of the Lake District, it is double that of the New Forest. The sheer variety of its unblemished landscape is compelling, and ranges from remote upland fell, crag and rambling moor through ancient woodland and rolling pasture to tidal marsh and coast. Threading through it all is the Lune itself, a river of ever-changing mood sustained by countless springs, becks, streams and lesser rivers, which each display a different facet of the valley’s beguiling character.

A moment’s pause to enjoy the view along Bowderdale (Walk 4)

Although surrounded by mountainous ground, the abrupt mass of the Howgill Fells stands apart and is obviously different from all around. Severed from the volcanic rocks of the Lakeland hills by the Lune Gorge, and from the Dales limestone by the Dent Fault, the daunting flanks guard a citadel of high plateau grounded on ancient shales and sandstones, which is deeply incised by steep-sided, narrow valleys that penetrate its heart. Any approach from the south demands a stiff climb to gain the broad, grassy ridges that radiate from its high point, The Calf, but if you settle for a longer walk the more gently inclined fingers that extend to the north offer something less energetic but equally rewarding. The tops have been rounded smooth by erosion over countless millennia to leave few crags or rocky faces; however, where they occur, they can be dramatic and create impressive waterfalls. Unlike the neighbouring hills, the fells have never been fenced or walled, and grazing livestock and wild ponies wander unimpeded across the slopes. The walker, too, can range at will and experience a wonderful sense of remoteness, although a paucity of unambiguous landmarks and the confusing geography of the ridges can make navigation something of a challenge when the cloud is down.

Flanking the infant Lune to the north are the more gently rising slopes of Great Asby Scar, which is protected as a National Nature Reserve for its expanse of limestone pavement. Scoured of their overburden by the moving ice sheet, and subsequently littered with erratic boulders as the ice retreated at the end of the last ice age, the bare limestone beds are crazed by grikes (fissures created as the slight acidity of rainwater exploits natural cracks and crevices). The deep fissures separating the clints (blocks) collect windblown soil and moisture, and harbour a surprising range of plants and even occasional trees that would otherwise be unable to survive these desert-like conditions.

Looking back to Grayrigg Common and Tebay Fell (Walk 13)

Collecting the waters flowing from the peaty mosses flanking the Shap Fells, the river turns abruptly south at Tebay to enter the Lune Gorge. Squeezed between steeply rising hills, the valley follows the line of a geological fault, which was further deepened by ice moving from the north. It is perhaps the Lune’s most dramatic section, and, despite the fact that both railway and motorway have been shoehorned in alongside the original road, the river retains a delightful separateness and one can meander through, oblivious of the intrusion. The heights on either side offer superb views across the valley, and the twisting gorge of Carlin Gill is one of the Howgills’ particular gems. Entering from the west, Borrowdale is another little-known delight. Simply wandering along the base of the secluded valley is enjoyment in itself, but include the traverse across Whinfell Common and the day could not be more complete.

Motorway and inter-city rail break out of the valley at Lowgill, leaving the river to a gently wooded passage below the lesser hills of Firbank Fell. As the gorge then opens out beyond the Howgills, the River Rawthey joins the flow, bringing with it the River Dee from Dentdale and Clough River out of Garsdale. The hills now take a step back, allowing the river to snake across a broad floodplain that extends all the way south until the valley of the Lune is abruptly constricted once more at Kirkby Lonsdale. The heights of Middleton Fell are a fine vantage, revealing a dramatic glimpse into Barbondale and across to Crag Hill and Whernside, while the dales converging on Sedbergh and the lower hills around Killington offer alternative perspectives on the river’s middle course.

Below Kirkby Lonsdale the valley opens wide again, and the bluffs on the western bank – although lower than the hills rising to the east – tend to nudge the river on its way. Things were not always so, for the Lune’s course over time has been erratic, and old banks, stranded pools and dry channels betray where it once flowed. Rivers from the limestone heart of the Yorkshire Dales enter from the east, where the flat-topped summit of Ingleborough erupts as a dominant landmark. The karst landscape of the area is noted as much for what lies below the surface as above, and an amble into the valley of Leck Beck reveals some of the portals to this hidden world. Further south lie the Bowland fells, another neglected moorland upland where walkers can experience unfettered wandering and expansive panoramas, a contrast to the tracts of ancient woodland to be found in the deep vales that drain it.

Beyond Springs Wood, the path briefly closes with Leck Beck (Walk 25)

Approaching Lancaster, the River Lune becomes tidal and enters its final phase. At the city’s maritime height, the riverbanks were hives of activity, lined with mills, shipyards, quays and warehouses. Some of the old buildings remain, having found new life as residential accommodation, but elsewhere today’s commercial enterprise no longer depends upon the river and instead faces towards the streets and roads. The riverbank now forms part of a Millennium Park that follows the Lune from Caton to Glasson, a pleasant, traffic-free conduit for walkers and cyclists to and from the heart of the city along the line of a former railway. Its centrepiece is a striking modern bridge spanning the river at Lancaster that brings in another trail from the coast at Morecambe.

Skirting a belt of low drumlins, formed from till deposited along the coastal fringe of glaciation, the Lune winds on to its estuary, where it finally breaks free of the land. Enclosure and drainage during the 19th century have reclaimed some of the low-lying moss (coastal marsh) as farmland, but beyond the flood dikes there remains a vast area of tide-washed mud, sandbanks and grazing salt marsh. The Plover Scar Light marks the obvious end of the river, but its channel is mapped between the sands for a further 4 miles (6.4km) to the Point of Lune, where it finally loses its identity within Morecambe Bay.

History

Man’s impact on the Lune catchment and corridor has been, in many ways, less intrusive than it has on many of Britain’s other rivers. Nevertheless, it remains very much a man-made landscape. Prehistoric climate change and clearance of the upland forests for farming have created the open moorland we value today, and the network of field and pasture along the valleys is the product of generations of agricultural management.

Although meagre, visible evidence of man’s ancient presence can be found upon the landscape. While not rivalling the scale of Stonehenge, there are stone circles on the flank of Orton Fell and above Casterton, and there are several known settlement sites, including an area above Cowan Bridge and, of course, the massive fort on top of Ingleborough.

The Romans used the trough of the Lune as a route north from forts at Lancaster and Ribchester. Their road followed the valley all the way to Tebay before climbing over Crosby Ravensworth Fell, and there were camps beside the River Lune opposite Whittington and at the foot of Borrowdale.

Later, the valley fell under the authority of Tostig, Earl of Northumberland and brother of Harold Godwinson, the last Anglo-Saxon king of England. Tostig’s ambitions for the throne ended with his death at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in September 1066, but Harold’s victory was short-lived, for within the month William, Duke of Normandy landed at Pevensey, and on 14 October defeated Harold at Hastings.

St Mary’s Church in Kirkby Lonsdale is a fine Norman building, although an even older church previously stood on the site (Walk 23)

The Normans quickly established their authority in the southern part of England, but the north was a different matter. The Lune Valley became seen as a strategic frontier passage, and for a time, the Welsh Marches apart, it was one of the most heavily fortified areas in the country, with some ten motte and bailey castles being built in and around the valley between Tebay and Lancaster.

But normality slowly returned, and the Norman age saw the founding of many religious communities up and down the country, with isolated riverside settings often chosen as the site of an abbey. Much of the upper Lune was incorporated within the estates of monasteries as far away as Byland in Yorkshire, yet only three houses were established within the valley itself. The ruins of a small Gilbertine priory can be seen at Ravenstonedale, while St Mary’s at Lancaster is a priory church founded under the Benedictines. The third monastery was on the coast at Cockersand, established by the Premonstratensian order.

The only significant settlement along the river’s course, Lancaster developed as a port and centre of manufacture, but the power of the river and its side-streams was never exploited on an industrial scale in the way of other Lancashire and Yorkshire rivers. As the river was not navigable above Lancaster, the hinterland was left relatively remote from other areas, and any small centres served largely local needs. Thus, when the canal age arrived, there was no industry to justify investment in extending the Lancaster Canal into the Lune Valley. The railway engineers, like the Romans, saw it purely as a convenient route to the north, although Tebay and Barbon saw a brief expansion with the line’s arrival, and the brick industry at Claughton benefited from its passing.

Completed in 1860, the Lune Viaduct carried the railway between Ingleton and Lowgill (Walk 14)

Today’s travellers often pass through the area on the way to the better-known attractions of the Lake District and the Yorkshire Dales, and earlier travellers were no different. William Gilpin had his sights set upon the lands beyond the ’bay of Cartmel’, and passed through Lancaster on his way to Kendal. The castle failed to impress, ’an indifferent object from any point’, but the Lune he regarded as a ’notable piece of water, [which] when the tide is full, sufficiently adorns the landscape’.

In 1772 Lancaster’s quay was busy with ships, and Gilpin ventured a little way upriver to describe its passage through Lonsdale. His words might very well apply today, ’where quietly, and unobserved, it winds around projecting rocks – forms circling boundaries to meadows, pastured with cattle – and passes through groves and thickets, which in fabulous times, might have been the haunt of wood-gods. In one part, taking a sudden turn, it circles a little, delicious spot, forming into a peninsula called vulgarly, “the wheel of Lune”.’

Three years earlier while on his way to Settle, Thomas Gray had gazed up the valley towards Ingleborough and been moved to pen ’every feature which constitutes a perfect landscape of the extensive sort is here not only boldly marked, but in its best position’. JMW Turner stayed a little longer to capture the scene at the Crook o’Lune and painted a landscape from beside the church at Kirkby Lonsdale. The picture so impressed Ruskin that he took the trouble to go and see for himself and the spot became known as ’Ruskin’s View’ and not Turner’s.

Wildlife

With little habitation and no industry along its course, the River Lune is one of England’s cleanest rivers and consequently rich in wildlife. It is one of the most important salmon rivers in the country, and the fish returning upriver from the Atlantic to breed can sometimes be seen leaping from the water. Sea and river trout are also among the fish frequenting the river. Once abundant, too, were eels that breed in the Sargasso Sea but grow and mature in the estuaries and rivers of western Europe. Rare, but still present, are colonies of white crayfish and pearl mussels, and conservation projects are being undertaken to improve their habitats.

Otters might be spotted, and there are known to be several holts from Halton all the way up to Tebay, although the Crook o’Lune is a good place to watch for them. Badger, roe deer, fox and hare all roam the surrounding countryside as, of course, do rabbit and grey squirrel. Britain’s native red squirrel, however, is now rare, but remains precariously established at the top end of the river around Newbiggin.

A hare in Bretherdale (Walk 8)

Above all, birds can be seen wherever you go, and a field guide is an indispensable companion. Beside the river, heron, oystercatcher, sandmartin, goosandar and ducks are all common, but keep a look out as well for the kingfisher. Wander into the wooded tributary valleys to find warblers, flycatchers and woodpeckers, with dippers and wagtails flitting around the streams. Barn owls, too, roam the area, their main food being small mammals such as voles. The moors are important nesting sites for lapwing, curlew and golden plover, and upon the Bowland hills can be found the merlin, Britain’s smallest falcon, and the hen harrier, which the AONB has adopted for its logo. Many species come to the estuary to feed and, dependent upon the tide, you may well see flocks of waders, geese and swans.

Even at the edge of Lancaster, there is plenty of bird life to be seen by the river (Walk 35)

Grazing and agriculture have displaced the flower meadows that would once have spilled across the valley, but hedgerows and an abundance of small natural woodlands in the many deep side-branches mean that the area remains rich in wildflowers. Oak, ash, hazel, alder, holly and hawthorn provide cover for a wide range of flowers, with carpets of snowdrops, ransoms and bluebells as well as many other species being commonly found. Flowers are at their best in spring and early summer, but late summer is the time to appreciate the full glory of the moors, when the heather is in flower. Autumn brings the rich colour of turning leaves, but is also the time when the mysterious world of fungi comes into its own.

Transport

All sections of the Lune Valley are readily accessible from the M6 motorway, and Lancaster, Oxenholme (on the eastern fringe of Kendal) and Penrith stations are all on the West Coast line.

Local bus services visit some villages, but rural timetables are not always geared to the needs of walkers, and it is as well to check details in advance (www.traveline.org.uk).

If you travel by car, be aware that the lanes of the area are generally narrow, winding and occasionally steep and were never intended for today’s traffic. Extra care is needed as slow-moving farm vehicles, animals, pedestrians, horse riders and cyclists may lie around any corner. Wherever possible use official car parks, but if none is available, park considerately and ensure that you do not obstruct field or farm access or cause damage to the verge.

Farmers have their ways and means of herding sheep – you never know what might be round the next bend in the road (Walk 19)

Accommodation and facilities

Hotels, bed and breakfast and self-catering cottages are widely available at the main centres of Lancaster, Kirkby Lonsdale and Sedbergh, as well as in many of the villages. There is also a good selection of camping and caravan sites. (For websites giving accommodation details, see Appendix C.) The many local pubs, restaurants and cafés offer appetising menus, often based around locally produced foods and specialities. There are banks and post offices at the main centres, but several hamlets have regrettably lost all their services, including the local shop and pub. As elsewhere in the country, mobile phone coverage is biased towards centres of population, and in the hill areas reception can be patchy.

The tiny hamlet of Aughton (Walk 32)

Navigation and maps

The mapping extracts (1:50,000) accompanying each walk in this guide indicate the outline of the route and are not intended as a substitute for taking the map itself with you. The context of the wider area given by the larger scale (1:25,000) OS Explorer maps will not only add to the enjoyment of identifying neighbouring hills and other features, but is vital should you wander off course or need to find an alternative way back. Reference to the route description and appropriate map will avoid most navigational difficulties, but on upland routes competence in the use of a compass is necessary, particularly if there is a risk of poor visibility.

A view across the foot of Lunesdale from a splendid stone stile (Walk 5)

A GPS receiver (and spare batteries) can be a useful additional aid, but you should know how to use it and be conscious of its shortcomings. Be aware of your own limitations and do not start out if anticipated conditions are likely to be beyond your experience. If the weather unexpectedly deteriorates, always be prepared to turn back.

The area is covered by Ordnance Survey maps at both 1:25,000 and 1:50,000 scales, but the larger scale shows a greater detail that is often invaluable.

The Ordnance Survey Explorer maps for the walks in this guide are listed below.

OL19 (Howgill Fells and Upper Eden Valley)

OL7 (The English Lakes, South Eastern area)

OL2 (Yorkshire Dales, Southern and Western areas)

OL41 (Forest of Bowland and Ribblesdale)

296 (Lancaster, Morecambe and Fleetwood)

Planning your walk

Safety

None of the routes described in this book is technically demanding, but be aware that after very heavy rain rivers and streams can flood, rendering paths beside them temporarily impassable. A handful of walks venture onto upland moors, where paths may be vague or non-existent and conditions can be very different from those experienced in the valley. The weather can rapidly deteriorate at any time of year and inexperienced walkers should be aware that it is easy to become disorientated in mist.

Walking with a companion can add to the enjoyment of the day and provide an element of safety. If you venture out alone, it is a good idea to notify someone of your intended route and return time, rather than leave a note on the dashboard of your car as an open invitation to a thief.

Following the simple and common-sense advice below will help ensure that you get the best out of the day.

Timings

Plan your walk in advance, bearing in mind your own and your companions’ capabilities and the anticipated weather conditions for the day. The times given in the box at the start of each walk are based on distance (2½ miles per hour) and height gain (1 minute per 10m of ascent), but make no allowance for rest or photographic stops along the way. They are provided merely as a guide, and in practice your own time may significantly differ, depending upon your level of fitness, ability to cope with the terrain and other factors such as weather.

Heading towards Arant Haw in the Howgills under glowering skies (Walk 15)

Gradient, poor conditions underfoot and lousy weather can add considerably to both time and effort. If you are new to walking, begin with some of the shorter or less demanding walks to gain a measure of your performance.

Footpaths and tracks

The network of public footpaths and tracks in the area is extensive, and signposts and waymarks are generally well positioned to confirm the route. On the upper moors, and indeed across many of the valley meadows, the actual line of the path is not always distinct, but the way is often discernible along a ‘trod’. Defined as a ‘mark made by treading’, a trod, by its nature, becomes increasingly obvious the more it is walked, and indeed may develop over time as a path. But on the upper slopes it is a less tangible thing – a slight flattening of the grass punctuated by an occasional boot print. A trod may differ from a sheep track only in that it has purposeful direction, and an element of concentration is often required to stay on the right course.

Clothing and footwear

Wear appropriate clothing and footwear and carry a comfortable rucksack. The variability of British weather can pack all four seasons into a single day – sun, rain, wind and snow, with the temperature bobbing up and down like a yo-yo. All this makes deciding what to wear potentially difficult, but the best advice is to be prepared for everything, and with today’s technical fabrics this is not as hard as it may seem.

Lightweight jackets and trousers can be both windproof and waterproof, without being too cumbersome should the weather improve. Efficient underlayers of manmade fabric wick away the damp to keep you warm and dry, and throwing in an extra fleece takes up little extra room. Good quality socks will help keep feet comfortable and warm, and don’t forget gloves and a hat. In summer, a sun hat and lotion offer protection against UV, and shorts aren’t always a good idea, particularly where there are nettles and brambles.

Whether you choose leather or fabric boots is a matter of personal preference, but ensure that they are waterproof rather than merely water-resistant. Boots should, of course, be comfortable and offer both good ankle support and grip.

Food and drink

A number of walks pass a pub or a café at some stage, but if you are intending to rely on them check in advance that they will be open. Even so, it is always a good idea to carry extra ’emergency rations’ in case of the unforeseen. Ensure, too, that you carry plenty to drink, particularly when the weather is warmer, as dehydration can be a significant problem.

Using this guide

This collection of walks includes something for everyone, from novices to experienced ramblers, and the routes range in distance from 3 to 11 miles (4.8 to 17.7km). While the lengthier walks require an appropriate degree of physical fitness, none demands scrambling or climbing ability. The area is hilly rather than mountainous, and gradients are generally moderate, with any steep sections usually brief.

All the walks are either circular or there-and-back walks, and so return to the starting point. They are arranged geographically in the guide, starting with the walks in the north of the region and gradually following the river southwards to the sea.

Each route description begins with a box that provides essential information about the walk, including the distance and time, as well as details of useful facilities such as refreshments, toilets and parking. In the route description, key navigational places and features are shown in bold.

Three appendixes provide a route summary table (Appendix A), a description of a longer route from one end of the Lune Valley to the other (Appendix B), and a list of contact details (Appendix C).

Enjoying a walk beside the Lancaster Canal (Walk 37)