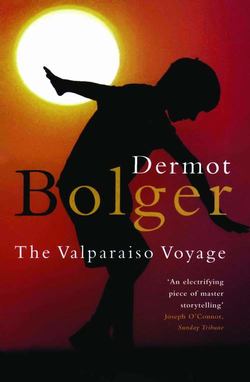

Читать книгу The Valparaiso Voyage - Dermot Bolger - Страница 7

I SATURDAY

ОглавлениеNavan, Co. Meath. Thriving hometown of carpets and wooden furniture. Warehouses and showrooms, neat factories dotting its outskirts. Strong farmers’ wives who would arrive in during my childhood to search for bargains, while their husbands belched and, with top buttons undone, slept off enormous lunches in broad armchairs in the hotel lounge.

Navan. With narrow streets as tight as a nun’s arse, falling downwards to where the Boyne and Blackwater meet. The fulcrum of Market Square where a kindly barber had clipped hair for half a century, discussing painting and amateur drama, rarely mentioning his nights on the run in an Old IRA flying column. An unlovely trinity of streets spreading out from it: Ludlow, Watergate and Trimgate.

Their medieval gates are long felled, their town walls disappeared. An ugly motorway scars the landscape now, necklaced by new estates with Mickey Mouse names. Dublin commuters forced into exile here by rising house prices, resenting their daily drive thirty miles back into the capital and suspicious of locals who are more suspicious of them. Outsiders and blow-ins circling each other around the closed fist of my native town.

‘Navan itself has little to detain you,’ The Rough Guide to Ireland says. A pity that one unfortunate black sailor at the start of the nineteenth century didn’t heed this advice. Hiring a rig of horses when his ship docked in Dublin after a voyage from some exotic foreign port, he took off through the morning rain to explore this land. It was noon when his black horses trotted into Market Square in Navan. He climbed down, his black boots and cloak startling the gaping locals. He found the local tavern and ordered. The innkeeper served him with true Irish hospitality, then withdrew to join the throng on the street, none of whom had ever seen a black man before.

They decided that there was only one person he could be. Old Nick, Lucifer himself come to tempt them. A rope was fetched, a horse chestnut tree selected in the field where my street was later built. It was the final lynching in the Royal County of Meath. This story doesn’t make The Rough Guide, nor any of the historical brochures welcoming visitors in the tourist office on Railway Street. Perhaps it was just a myth invented by Pete Clancy to frighten me as a boy. It certainly succeeded, hearing the creak of a tree at night beyond the outhouse where I slept, expecting to see a dark body still twitching in mid-air if I peeped out through the chicken wire.

Who ordains which stories are remembered and what tales discreetly forgotten in any town? Were there many in Navan who recalled mine, with my family gone? Few would wish to be reminded, in this new traffic-choked prosperity they live in. Yet nobody can control the ghosts that haunt these streets. Lost foreign sailors; starved serving girls who shivered, waiting for their muscles to be felt at hiring fairs; barefoot messenger boys who contracted gangrene by running with open sores through worm-infested horse dung on the cobbles; our local poet, Ledwidge, killed by a stray shell at Ypres and appearing to a friend that same night outside the Meath Chronicle printing works. I just knew that such ghosts existed, because, walking up Flower Hill, I was taking my first step amongst them.

Opening her garden gate everything looked the same, even the way the estate agent watched me from the doorway. Lisa Hanlon’s father had stood in that spot once, an old man who avoided my eye, wary of finally admitting me onto the premises.

I took the estate agent’s brochure and gave a false name and phone number. Not that anyone was likely to recognize me, but I still felt nervous pushing open the sitting-room door. The electric heater set into the old fireplace remained in place, as did the nest of small tables, the thickset re-upholstered armchairs and the long sofa with its lace frills. This room was always too choked with reminders of Lisa’s childhood and mine.

It had felt strange making love to her here, when we were both twenty-two, while her younger self looked down from a gold-framed communion photo. That mouth, which looked so devout after receiving its first wafer of Christ, surprising me by its sudden wantonness.

But at twenty-two I wasn’t that interested in Lisa, to be honest; the attraction behind our brief affair was more about gaining access to this sitting-room. Listening to her parents ascending the staircase, enjoying the sense of danger that they might come back down. I remember Lisa’s astonishment at my ability to grow erect again so quickly after I came. She was quiet and plain. Possibly no man had ever been this passionate in her presence before. But I couldn’t explain how it wasn’t her tiny breasts, still pert as a schoolgirl’s, which excited me. It was being able to fondle the furniture – the uncomfortable cushions on the sofa, the patterned carpet faintly reeking of mothballs, the never-to-be-touched china plates in the sideboard, the ornaments from the parish’s first Diocesan Pilgrimage to Lourdes. The cloying scent of small-town respectability that I was always excluded from.

If Lisa had left me alone on those nights I might have simply carried on making love to the furniture. Here on the lit side of Hanlon’s sitting-room window at last. Not crouched outside in the cold, like on the evenings when I had risked climbing from our outhouse roof down into Casey’s garden next door. Creeping from there into Hanlon’s garden to peep through apple branches at Lisa’s mother drying her only daughter’s hair, reading her bedtime stories, bringing in hot milk and biscuits while they watched television together in winter.

She would switch the light off so that the sitting-room was lit by a glowing coal fire, with images from the unseen television literally transposed across their faces. At least that was how I saw it from outside, at the age of ten and eleven, living out those television programmes at second hand by mimicking the expressions on their faces. I laughed when they laughed and ducked down if they glanced towards the window, even though I knew they could not see me crouched against the hedge.

I could always tap against Casey’s kitchen window and Mr Casey would chance taking me in for an hour to get warm. Some nights I was hungry enough to swallow my pride and risk doing that, though twice I was discovered and beaten for it, with my father shouting at our next-door neighbour across the hedge to mind his own business. But the fact that sanctuary was obtainable in his kitchen made me view Mr Casey as inferior. Hanlon’s house was impenetrable, with its warmth as unimaginable as sex. Hunger didn’t lure me to spy on Lisa’s window. It was to live out a fantasy where I imagined myself allowed to add coal to the fire with the brass tongs and have someone brush my hair instead of yanking at it with a steel comb.

The estate agent coughed in the doorway behind me now. I had forgotten about his presence. Other viewers moved noisily around upstairs, testing the floorboards, checking walls for dry rot, envisaging attic conversions and PVC windows.

‘Why is it for auction?’ I asked.

‘An executor’s sale. The old woman who lived here died. Her daughter lives in England.’

‘Is she home now?’

‘Why do you ask?’ The estate agent was careful of his profit margin. Too many tales of under-the-table bribes to owners, desperate illegal bids from desperate people trapped by the housing shortage in this new booming economy.

‘I’d just feel self-conscious looking around a house if I felt the owner could be watching.’

‘We encourage people to stay away while their homes are being shown,’ the man replied. ‘It’s better for everyone. She’s coming home on Thursday morning for the auction in the Ard Boyne Hotel that afternoon.’ He scrutinized me carefully. ‘At three thirty. You’re leaving it late if you want to bid. Most people have already had it surveyed and are just taking a last look.’

‘I’ve been abroad. I only saw it in the paper today.’

They were the first true words I had spoken. The ad was in the property section of a discarded Irish Independent, which I pocketed at Dublin airport this morning when passing through the first-class section of an Aer Lingus flight from Lisbon. Maybe it was cold feet at actually being back in Dublin, but after the airport coach reached Busaris I’d sat on a bench, too terrified to venture out. When a bus to Navan was announced I had left my bags in a locker and boarded it, thinking that Navan seemed as good a place as any to start my homecoming.

The estate agent walked back out into the hallway to hand a brochure to a young couple, launching into his patter about the south-facing garden and how, with the motorway, it was less than an hour’s drive from Dublin.

Why had I asked him about Lisa? The dead cannot intrude on the living, even to apologize. She was one of the few people to have ever loved me. In return I had abandoned her, lacking the self-confidence to believe that anyone could truly care for me. Before meeting Miriam I had been afraid to let people get close, feeling they would only be disgusted when they uncovered the lice-ridden Hen Boy beneath the thin veneer of normality I’d gained in Dublin. At twenty-two I had been acting out a role every Thursday evening for seven weeks when I had washed and shaved and took the provincial bus back out here from the capital to visit Lisa. One of many roles I’d taught myself to hide behind, whereas Lisa was simply always just herself. Would she have understood if I had broken down and tried to explain the insidious stench of dirt and disgrace I carried inside? How could I, when I didn’t fully understand it myself back then? Instead – after enduring two hours of Country’n’Irish music down the town while we waited for Lisa’s parents to retire to bed – I would make love to her in this sitting-room, never slackening off in my terror that some tenderness might develop if we lay motionless for too long.

Now I pulled out the electric fire to examine the grate behind it. On the first night she brought me home I had been intensely disappointed to discover this two-bar monstrosity blocking the fireplace where flames used to light her face. We’d only met by fluke when snow prevented racing at Newton Abbot and I was forced to return to Navan dog track for the first time in a decade because it was the only place where I could place a bet on a freezing January evening.

‘This heats the room in no time,’ Lisa had said, plugging in the fire, tipsy from the champagne I’d splashed out on after sharing the tote jackpot with six other punters. ‘Don’t worry, I’ve warned my parents never to come down here when I’m with someone.’

But the fire’s dry heat didn’t feel right that night, nor her white skin or deep French kisses. Being real and available, they could never hope to match my gnawing hunger, any more than the gesture of buying champagne could change who I knew I was inside.

‘I used to wonder about you,’ Lisa had whispered afterwards. ‘The way people avoided mentioning you. What did you do to deserve all that?’

As a child I didn’t exactly know what I had done, just that I deserved such punishment and more. Wicked, dirty and dumb. ‘The Hen Boy,’ as Barney Clancy’s son, Pete, christened me at primary school. ‘Chuck, chuck, chuck, chuck – here comes the Hen Boy. Get up the yard and lay an egg, Hen Boy, there’s a smell of shite off you here!’ His taunting voice, two years older, four inches taller, and a dozen social castes above me. The son of my father’s Lord and Master. Children don’t talk in whispers. They understand small-town distinctions and lack adult inhibition about openly shouting them out.

The estate agent returned to hover behind me, concerned lest I damage the electric fire. He probably had a sixth sense to distinguish between potential bidders and nuisance viewers.

‘The house needs work, of course,’ he said, steering me from the sitting-room. ‘But just think what you could do with a little imagination.’

I had no interest in seeing the other rooms, but felt that it would look suspicious to depart. Old people leave something behind them in a house. Not a physical smell or even miasma, but the aftertaste of lonely hours spent waiting for a phone to ring. Everything about the kitchen looked sad – a yellowing calendar from the Holy Ghost Fathers, an ancient kettle, a Formica table that belonged in some museum. Its creeping shabbiness stung me, like a tainting of paradise. One should never go back, especially to Navan – a town so inward-looking it spelt its own name backwards.

Wallpaper had started to droop on the landing, with faint specks of mildew caused by a lack of heat in winter. Finally I was going to see upstairs. Lisa’s voice returned from nineteen years before: ‘Wait till they go on the pilgrimage to Fatima this summer. You can stay over, sleep in my bed. We can really do fun things then.’

A Dublin family clogged the stairwell as I squeezed past, sandwich-board people togged out in an array of expensive logos, trailing an aura of casual affluence behind them. Lisa’s room was empty. I knew it was her room. I had watched her here often enough as a child when she seemed unaware that if she closed the blinds by slanting them down instead of up her outline remained visible. Lisa who spent ten minutes each night brushing her long straight hair; who often stared into space, half-undressed, like her mind was switched off. Lisa aged eleven, twelve and thirteen, when her breasts made that single surge outward so that her body had looked the same silhouetted in this window as when I first saw her properly naked. Some nights she had remained at the window for so long that I feared she suspected me of spying on her. Eventually I had realized that she, in turn, was peeping through her blinds at the outhouse where she presumed that I was sleeping. Perhaps she had been as fascinated by my life back then as I was by hers.

I switched off the bedroom light which the estate agent had left on and raised the blind fully. Hanlon’s garden was now a wilderness with one apple tree cut down and the other besieged by sour cooking apples rotting in the unkempt grass. There was no way that I was going back out there. I had never quite banished their sour taste and the nausea that replaced my night-time hunger if I stole them.

Whoever now owned Casey’s house had built on a Victorian-style conservatory and a patio. A barbecue unit stood against the pebble-dashed wall replacing the hedge which once screened off my old garden next door. My father’s crude outhouse had been knocked down. A pristine building stood in its place, with a slated roof and arched windows strategically angled for light. A trail of granite stepping-stones twisted through a sea of white pebbles up to the newly extended kitchen. A Zen-like calmness pervaded the whole garden. I found my fingernails scraping against the glass.

Two elderly women entered the bedroom behind me, their Meath accents achingly familiar. I knew their names but didn’t turn around in case they recognized something about my face. As a weekend pastime, house viewing seemed like solitary sex – it was cheap and you didn’t need to dress up for it. With no intention of bidding, they gossiped about how much Hanlon’s house would fetch and what their own modernized homes were worth in comparison – immeasurable fortunes, leaving them weak-kneed at the very thought of auctions. I could imagine Cormac mimicking their accents: ‘I don’t know how you held out until it reached the reserve, Mrs Mulready, I’d already had my first orgasm just after the guiding price.’

‘God help any young couple starting out,’ one of them remarked, moving to stand beside me at the window. ‘Didn’t that American computer programmer make a lovely office for himself out in the Brogans’ garden?’

‘Poor Mr Brogan.’ Her companion blessed herself. ‘There was a lovely crowd at his funeral. A terrible way to meet your death. The guttersnipes they have in Dublin now, out of their heads on drugs!’

‘Maybe with all these scandals it’s just as well that he’s gone,’ the first woman said. ‘Mr Brogan was from the old school, not some “me féiner”.’

Her companion tut-tutted dismissively. ‘Sure the Dublin papers would make a scandal out of a paper bag these days. You get sick of reading them. They can say what they like about Barney Clancy now that he’s dead, but they’ve never proved a single thing. That man did a lot for Navan and the more they snipe at his memory the more people here will vote for his son.’

‘Don’t I know it.’ The first woman turned to go, sneaking a quick glance in my direction before dismissing me as another Dublin blow-in. ‘Still you’d feel sorry for Mrs Brogan, no matter what two ends of a stuck-up Jackeen bitch she could be in her day. The papers say she’s not long for this world with cancer.’

They moved on to the front bedroom, talking over my head like I didn’t exist.

I was almost fourteen when I left Navan. By seventeen I’d cultivated a poor excuse for a beard to conceal the onslaught of acne. It was never shaved off until the age of thirty-one. Clean-shaven and bespectacled now (even if the frames only contained plain glass), my dyed hair had receded so much that my forehead resembled my father’s. But I found that I had still sweated in their presence – perhaps half-hoping to be recognized. I touched Lisa’s single bed, kept made up for her during all the years she was away in England. I had never lain between its sheets, as she wanted. Nineteen years ago, on the final night when we returned here from the pub, her mother intruded upon the spell, overcome by curiosity or guilt as she blundered into the sitting-room with a tray of tea and biscuits that I knew Lisa didn’t want.

‘How are you keeping since the family moved to Dublin, Brendan?’

‘I’m keeping well, Mrs Hanlon.’

Her pause, then in a quiet voice: ‘I knew your mother. We went to Lourdes together. The first ever pilgrimage from this parish.’

Mrs Hanlon didn’t say any more. She didn’t need to, the pity in her eyes destroying everything. Their sly plea for forgiveness at having never lifted a finger to help. Suddenly I had ceased to belong in that room. I was an object of sympathy dragged in from outside; the boy raised by his stepmother in an outhouse. Indifference would have made me her equal. Hatred or distrust might have given me strength to screw her precious daughter so hard that Lisa’s cries would summon her mother back down to gape at us among the communion photographs and smashed china and knick-knacks from Lourdes. But her pity had rendered me impotent. Lisa’s parents might have been horrified by what my father did, but – like the rest of this town – they never stood out against him. Only Mr Casey ever did, and he got no thanks from anyone back then in their turn-a-blind-eye world.

After her mother left the room, I knew that Lisa was too nervous to make love. I hadn’t wanted to either. I’d simply longed to vanish back to the anonymity of flatland Dublin where no one knew or cared about me, except that I was Cormac’s slow-witted gambler of a brother, always in the bookies. It hurt me now to recall Lisa’s face as I left that night, aware that something beyond her comprehension was wrong as she urged me to phone and probably continued waving even when I was out of sight. And how I walked out along the blackness of the Dublin road after missing the last bus, although I knew how hard it was to hitch a lift after leaving the streetlights behind.

But I had needed to escape from Navan that night, just like I had to flee from Lisa’s house now. I descended the stairs, left the estate agent’s brochure in the hall, closed the gate and refused to glance towards the house, two doors down, into which my parents had once driven me home with such pride from the Maternity Hospital in Drogheda.

Athlumney graveyard on the Duleek Road out of Navan. Twice a year my father came here – on Christmas Eve and 12 November, my mother’s anniversary. He always arranged for 7 a.m. mass to be said for her on that day, calling me from sleep in the outhouse with an awkwardness that verged on being tender. He’d have rashers and sausages cooked for us to share in silence before anyone else was awake, watching the clock to ensure that we still managed to fast for an hour before communion. We drove, in our private club of two, to the freezing cathedral where the scattering of old women who knelt there glanced up at us. Afterwards in the doorway people might whisper to him, with supplications for Barney Clancy, our local minister in Government, to be passed on through his trusted lieutenant. An old woman sometimes touched my arm in a muted token of sympathy, as I shivered in the uneasy role of being a rightful son again. On our return from visiting the grave, my stepmother Phyllis would be up with the radio on and the spell dissipated for another year.

Standing now beside the ruined castle in this closed graveside I wondered what had possessed him to be buried with his first wife? Was it an act of atonement or another example of miserliness? My father, careful with his pence, even in death. In recent days the doctored version of his life had been freshly carved in gold letters on the polished black marble: Also, her loving husband, Eamonn, died in Dublin…

The wreaths from his funeral were not long withered, the earth still subsiding slightly so that the marble surround had yet to be put back in place. I hadn’t anticipated his body being laid here, where only the old Navan families retained rights, nor that I would feel a surge of anger at him for seizing the last possession that my mother owned.

I should remember something about her, a blur of skirts or just a memory of being hugged. It’s not that I haven’t tried to recall her, but I was either too young or have blocked them out. My first memory is here in Athlumney. Her coffin must have been carried three times around the outer boundaries, as was the tradition then, before being lowered into the earth. But all I recall is adult feet shuffling back from the graveside as someone let go my hand. I stand alone, a giddy sensation. A green awning covers the opened grave but through a gap I can see down – shiny wood and a brass plaque. When I scuff the earth with my shoe, pebbles shower down. I do this repeatedly until a neighbour touches my shoulder. I am three years and eight months of age.

It is night-time in the memory which occurs next. I wake up crying, with the street quiet outside and my room in darkness. Yellow light spills onto a wallpaper pattern of roses as my door opens. My father enters and bends over my bed, wrenched away perhaps from his own grief. He climbs in, rough stubble against my neck as his arms soothe me. How secure it feels as we lie together. I want to stay awake. A truck’s headlights start to slide across the ceiling, with cattle being ferried out along the Nobber Road. I love having this strong man beside me in the dark. I don’t remember waking to find if he was still there in the morning.

The polished floorboards in the outhouse come to mind next. I am playing with discarded sheets of transparent paper, crammed with lines and angular patterns which he allows me to colour in with crayons. Lying on my tummy to breathe in the scent of Player’s and Major cigarettes. His only visitors are men with yellow-stained fingers who laugh knowingly and wink at me as they talk. The extension bell on his phone frightens me, ringing so loudly down in the shed that it can be heard by half the street who are waiting the seven or eight years of wrangling, lobbying and political pull that it takes to have a phone line installed back then.

This was before my father was headhunted by Meath County Council as a planning official. He was simply a quantity surveyor, running his own business from a converted shed, which had been constructed in our garden by a previous owner as a hen-house. Here he received courtiers in a black leather swivel chair, men who tossed my hair, slipped me coins and excitedly discussed rumours of a seam of mineable zinc being located outside the town.

Some had business there, like Slab McGuirk and Mossy Egan – apprentice builders knocking up lean-to extensions and milking parlours for the bogmen of Athboy and Ballivor. Others, like old Joey Kerwin, with a hundred and forty acres under pasture near Tara, simply sauntered up the lane in search of an audience for their stories, like the mock announcement of a neighbour’s death to the handful of men present. ‘All his life JohnJo wanted an outdoor toilet, but sure wasn’t he too fecking lazy to dig it himself. He waited till the mining engineers sunk a borehole on his land, then built a bloody hut over it, with a big plank inside and a hole cut into it to fit the queer shape of his arse. The poor fecker would be alive still if he hadn’t got into the habit of holding his breath until he heard the fecking plop!’

I remember still the roars of male laughter that I didn’t understand. New York might have Wall Street but Navan had my father’s doorway, with men leaning against it to spit into their palms as they shook hands on deals. Occasionally raised voices were heard as Slab McGuirk and Mossy Egan squabbled about one undercutting the other. It took Barney Clancy to bang their heads together, creating an uneasy shotgun marriage where they submitted joint tenders for local jobs that the big Dublin firms normally had sewn up.

My first memories of Clancy are in that outhouse: the squeak of patent leather shoes that set him apart, the distinctive stench of cigar smoke, deeper and richer like his voice could be. The way the other men’s voices were lowered when he arrived and how his own accent could change after they left and himself and my father were alone. Often, after Clancy in turn departed, my father’s sudden good humour could be infectious. I would laugh along with him, wanting to feel in on his private joke, while he let me sit on his swivel chair. With my knees tucked in, the makeshift office spun around in a blur of wallcharts, site maps, year-planners and calendars from auctioneers; all the paraphernalia of that adult world of cigarettes and rolled banknotes, winks and knowing grins.

But I remember sudden intense anger from my father there too, how I grew to dread his raised voice. Just turned eight, how could I know which architectural plans were important and which were discarded drafts? A gust of wind must have blown through the opened door that day when my father saw Slab McGuirk out. Half-costed plans slid from his desk onto the floor. I still remember unfathomable shapes on the wafer-thin sheet as I began to colour them in, absorbed in my fantasy world. That was the only time he ever struck me until Phyllis entered our lives. Curses poured forth, like a boil of frustration bursting open. Curled up on the floor, I understood suddenly that everything was my fault. I was the nuisance son he was stranded with, perpetually holding him back.

Then his voice changed, calling me to him. Tentatively I dared to glance up at this man who was my entire world. His arms were held out. Old familiar Dada, beckoning and forgiving. Then the black phone rang. He picked it up. From his tone I knew that it was Barney Clancy. I might not have been there. His swivel chair was empty. I sat in it, with my ear throbbing. But I didn’t cry. Instead I spun myself round until the whole world was flying except for me, safe on my magic carpet.

The revolving slows to a halt in my mind. A bell rings, a crowd rising. Zigzagging on a metal track with its fake tail bobbing, I fret for the mechanical hare. The steel traps open, greyhounds pound past. Floodlights make the grass greener, the packed sand on the track sandier, the sky bluer above the immaculate bowl of light that was Navan dog track.

Men jostled around gesticulating bookmakers with their leather bags of cash. A young blonde woman laughed, teasing my father. I couldn’t stop staring at her, like somebody who seemed to have stepped through the television screen from an American programme into our humdrum world, except that her Dublin accent was wrong. The woman teased him again for not risking a small bet on each race, as she laughed off her loss of a few bob each time the bell went. But my father would have regarded the reverse forecasts on the tote as a mug’s game, when an average dog could be body-checked by some mongrel on the first bend. He would have been holding off to place one large bet on a sure tip handed to him on the back of a Player’s cigarette packet.

I was an eight-year-old chaperone on that night of endless crisps and lemonade when I first saw Phyllis. Hair so blonde that I wanted to touch it, her fingers stroked the curved stem of a gin and tonic glass. She didn’t smoke back then, her palms were marble-white. Her long red nails gripped my father’s arm when one of her dogs finally won, leaving an imprint on his wrist as we sat in silence while she collected her winnings.

I had four winners that night. If a dog broke cleanly from trap six with sufficient speed to avoid the scrum on the first bend it invariably featured in the shake-up at the end. Dogs in trap five generally faded, but trap four always seemed to get pulled along and challenged late if they had closing strength. The knowledge and thrill were instinctive within me, my heart quickening at the bell, my breath held for twenty-nine point five seconds, my ears pounding as time moved differently along the closing straight. Except that all my winners were in my head – they never asked if I wished to place a bet. Indeed, all night I had a sense of being airbrushed out as they spoke in whispers. They didn’t even spot my tears as I jigged on a plastic chair after soiling myself. It was my fault. I should have touched his arm to ask him could I go to the toilet on time, but was afraid to intrude on their private world until the stench alerted Phyllis.

I remember the cubicle door slamming and the marble pattern on the stone floor as shiny toilet paper chaffed my soiled legs. My father hissed in frustration while I gagged on the reek of ammonia cubes from the flooded urinals. Most of all I remember my shame as men turned their heads when he led me from the cubicle. Outside the final race was being run, with discarded betting slips blown about on the concrete and whining coming from dog boxes. Phyllis waited, shivering in a knee-length coat.

‘How is he now?’ Her voice was disconcerting as she glanced at me, then looked away. On the few occasions during the evening when I had caught her watching me I’d felt under inspection, but the brittle uncertainty in her tone made her sound like a child herself.

They walked together without touching, edging ever more fractionally apart as they passed through the gates. Lines of parked cars, the greasy aroma of a van selling burgers. I kept well back, suffocating in the stench of self-disgrace. They whispered together but never kissed. Then she was gone, turning men’s heads as she ran out between parked cars to flag down the late bus to Dublin. I didn’t know whether to wave because she never looked back.

It was Josie who cleaned me up properly before school next morning, standing me in the bath to scrub my flesh pink with thick bristles digging into me like a penance. My father didn’t have to warn me not to mention the blonde woman. Of late Josie was paid to walk me to school each morning and wait for me among the mothers at the gate. My afternoons were increasingly spent in her damp terraced cottage in a lane behind Emma Terrace, playing house with her seven-year-old granddaughter or being held captive by pirates and escaping in time to eat soda bread and watch F-Troop on the black-and-white television.

Cigarette smoke rarely filled the outhouse now, with the telephone jangling unanswered. The first mineshaft was being dug on the Kells side of town, the streets awash with gigantic machines, unknown faces and rumours of inside-track fortunes being made on lands that had changed hands. My father was away every second night, working in Dublin, while I slept beneath the sloping ceiling of Josie’s cottage. Her granddaughter shared her teddies, snuggling half of them down at the end of my bed after she swore never to tell my father or any boy from my school that I played with them.

It was Josie who found the first letter in the hall, opening up the house to light a fire for his return. She tut-tutted at the sender’s insensitivity in addressing it to ‘Mr and Mrs Brogan’. It was an invite for a reception in Dublin to announce details of the next phase of the mine. Some weeks later a second envelope arrived, this time simply addressed to ‘Mrs Phyllis Brogan’. Josie stopped in mid-tut, her tone scaring me. ‘But your mother’s name wasn’t Phyllis?’

It was Renee to her neighbours, but spelt ‘Irene’ on this gravestone in the quietude of Athlumney cemetery. Below my father’s recently carved name space existed for one more, but surely Phyllis could not intend to join them?

I knelt to read through the withered wreaths left there three weeks ago. ‘Deepest sympathy from Peter Clancy, TD and Minister for State’. ‘With sympathy from his former colleagues in Meath County Council’. A tacky arrangement of flowers contorted to form the word DAD could only have come from my half-sister Sarah-Jane. It resembled something out of a gangland funeral. Rain had made the ink run on the card attached to a bunch of faded lilies beside it, but I could discern the blurred words, ‘with love from Miriam and Conor’. I fingered their names over and over like an explorer finding the map of a vanished continent. Next to it lay a cheap bouquet, ‘In sympathy, Simon McGuirk’. It took a moment for the Christian name to register. Then the distant memory returned of a teacher in the yard labelling McGuirk as ‘Simple Simon’. Pete Clancy had battered the first boy who repeated that name as he offered McGuirk the protection of his gang and rechristened him ‘Slick’. It was only the thuggish simpleton himself who did not grasp that his nickname was coined in mockery.

Meanness and premature baldness were passed on like heirlooms in the McGuirk family. Slab’s son resorting to such extravagance perturbed me, but not as much as the small wooden cross placed like a stake through the heart of the grave. I only spotted it as I rearranged the wreaths. My father must have placed it here some time in the past decade. The unexpected gesture shocked me. I knelt to read the inscription: Pray also for her son, Brendan, killed, aged thirty-one, in a train crash in Scotland.

Market Square. The old barbershop was gone; its proprietor one of the few kindly faces I remember. A boiled sweet slipped into my palm on those rare occasions when I was allowed to accompany Cormac there. Mostly my father cut my hair himself, shearing along the rim of an upturned bowl. A video outlet stood in its place, between a mobile phone store and a discreet lingerie window display in a UK High Street chain-store. Shiny new toys for the Celtic Tiger. McCall’s wooden-floored emporium had disappeared, with its display of rosary beads threaded by starved Irish orphans with bleeding fingers who were beaten by nuns. Instead, music blared from a sports store displaying cheap footballs handsewn by starved children with bleeding fingers in safely anonymous countries.

The Dublin buses still stopped outside McAndrew’s pub, where an ‘advice clinic’ caravan was double-parked, belonging to Pete Clancy. No election had yet been called, but with the delicately balanced coalition only hanging by a thread, more experienced politicians were getting their retaliation in early. Pete Clancy’s face stared from a poster, like a touched-up death mask of his father. I recognised the two men dispensing newsletters outside the caravan, though their faces had aged since their days as young Turks laughing in my father’s outhouse. They were mere footsoldiers now, ignored by the younger men in suits talking on mobile phones in the caravan doorway.

Jimmy Mahon was the older of the two. A teetotaller barman, he had been nicknamed ‘the donkey’ by Barney Clancy who got my father to dole out the most remote hamlets for him to canvass. Mahon was known to work all night on the eve of an election, leaflet-bombing letterboxes. He would have happily died for Barney Clancy and reappeared as a ghost to cast a final vote for him. At one time there were dozens like him in Navan, but now he cut a lonely figure as he approached the bus queue, impassive to the cynicism and indifference of Saturday afternoon shoppers. He reached me and held out a leaflet.

I stared back, almost willing him to recognize me without the beard. Three weeks ago he had probably followed the cortege here from Dublin at my father’s funeral and perhaps knelt unwittingly in the same pew as the man who killed him. He glanced at me with no recognition in his eyes, then passed on. The four-page leaflet contained eleven pictures of Pete Clancy, claiming personal credit for every new traffic light, road widening, tree planting, speed ramp, public phone or streetlight installed in Meath over the past six months. As old Joey Kerwin used to joke, the Clancys only just stopped short of claiming credit for every child conceived in the constituency. Help me to help you, a headline proclaimed on the last page. Contact me at any time at my home phone number or by e-mail. I almost discarded the leaflet like most of the bus queue, but then pocketed it, deciding that the e-mail address would be useful.

The first bus to arrive was a private coach from Shercock. I boarded it, wondering if anyone in that small town still remembered Peter Mathews, a petty thief who limped into town on a crutch and got caught withdrawing money from a stolen post office book, which he hid before the guards came. He found himself stripped and bent over a chair in the police station. He found himself dead from a heart attack with his pancreas bleeding from a blow to the stomach. Guards who’d had better ways to spend their Saturday afternoon contradicted each other in court. Swearing in the jury, the judge asked anyone if they had to declare an interest in the case. One juryman had spoken up. ‘I have no interest in the case, Your Honour, I’m not interested in it at all.’ He might have been a spokesman for my father’s generation. ‘I have no interest in seeing what’s in front of my eyes, no interest in things I don’t want to know about. If people didn’t turn a blind eye, Your Honour, we’d all be fucked.’

Half the bus would be fucked tonight if they got the chance, I suspected as I looked around it. Thick-calved Cavan girls wearing skirts the size of a mouse’s parachute and platform heels that needed health warnings for acrophobia. They shared lipstick and gossip in a suffocating reek of perfume. A radio almost drowned out the lads behind me discussing the new satellite channel a local consortium had set up to beam video highlights of junior local hurling matches into selected pubs until 10 p.m., when the frequency was taken over by a porn channel from Prague.

We crossed the Boyne near the turn for Johnstown. To the left a line of mature trees blocked out any view of the Clancy family residence, a Palladian mansion with an additional wing built on by Slab McGuirk and Mossy Egan the year my father left private employment. County Council workers had extended a six-foot stone boundary wall for free when the road was being widened. Beyond it the road grew lonely, broken by the lights of isolated homesteads and livestock huddled in the corners of fields. I stared out into the dusk as we reached the first turn for Tara, the dung-splattered seat of the ancient High Kings.

‘Let’s stop at Tara, I’ve never seen it,’ Phyllis had pleaded as we passed here on the second occasion I met her, six months after our night at the dog track. By then, the secret was all over Navan about my father having remarried. Nobody seemed sure about how long he had been living a double life in Dublin or why he told none of his old friends. But people were impressed by stories of Barney Clancy being best man at the wedding and treating them to dinner in the Shelbourne Hotel. Brian Lenihan and two other Government ministers were rumoured to have joined in their celebrations, which became a near riot when Donough O’Malley arrived and my father reluctantly allowed his wedding night to be hi-jacked, flattered by the attention of such great men.

My father ignored Phyllis’s request to stop at Tara in the car that day. Her interest in seeing it would have been negligible. But her apprehension and self-doubt about having to confront her new neighbours was evident, even to me, two months past my ninth birthday. Even the way she spoke was different from how I remembered her Dublin accent at the dog track, so that she seemed like a child unsuccessfully trying to sound posh.

My father, on the other hand, wanted the business finished, with his new bride installed and the whispers of neighbours faced down. He had accepted the job of heading a special development task-force within the planning department of Meath County Council and needed to live in Meath full-time. A more than respectable period of mourning had passed since my mother was knocked down by a truck on Ludlow Street, and it was several years since Phyllis’s first husband, a Mr Morgan, passed away in his native Glasgow, leaving her with one son, Cormac, a year younger than me.

Neither Cormac nor I spoke to each other on that first journey into Navan. Cormac looked soft enough to crush, pointing out cattle to his teddy bear through the window and keeping up an incessant, lisping commentary. We shared the same freckles and teeth but his hair was a gingery red. Even though I was preoccupied in struggling against back-seat nausea, I could see the effect that his whispered babbling and the unmanly teddy bear were having on my father.

‘Does this mean we’ll be going to see the dogs again?’ I asked.

‘You never saw your mother at the dog track. She was never there. Do you understand?’

My father didn’t turn as he spoke, but his eyes found mine in the rear-view mirror. Mother. Was that what I was meant to call her? Half the town probably saw them at the dog track, but to my father power was about controlling perceptions and this was to be his wife’s stage-managed arrival into Navan.

Some time during their first night in the house I cried out. Perhaps my tears were caused by a sense of everything changing or maybe the inaudible shriek of a ghost being banished woke me, with no untouched corner left for my mother to hide in. All evening the house – already immaculately cleaned by Josie, whose services were now dispensed with – had been scrubbed by Phyllis. Neat cupboards were pulled apart like an exorcism, old curtains torn down before her new Venetian blinds had even arrived, and alien sounds filled up the house.

I just know that I cried out again, waiting for the creak of his bed in response and for yellow light to spill across the pattern of roses. Cormac’s eyes watched like a cat in the dark from the new camp-bed set up across the room. But it was Phyllis who entered to hover over my bed. My crying stopped. How often have I relived that moment, asking myself who Phyllis was and just how insecure she must have felt? A young twenty-five years of age to his settled, confident thirty-eight. Had they been making love, or did I startle her from sleep to find this house – twice the size of the artisan’s cottage she was reared in – closing in around her like a mausoleum to the goodness conferred by death onto another woman, knowing she would have to constantly walk in that other woman’s footsteps, an inappropriately dressed outsider perpetually scrutinized and compared.

Her hand reached out tentatively towards my wet cheeks, her white knuckle showing off a thickset ring. I flinched and drew back, startling Phyllis who was possibly more scared than me. Eyeball to eyeball with a new life, sudden responsibilities and guilts. We were like two explorers wary of each other, as she stretched out her fingers a second time, hesitantly, as if waiting for me to duck away.

‘Why were you crying?’ Her voice, kept low as if afraid of wakening my father, didn’t sound like a grown woman’s. I didn’t know what to say. ‘Were you scared?’

‘Yes.’

It wasn’t me who replied; it was Cormac, his tears deliberately staking his claim to her. Phyllis turned from my bed, crooning as she hugged her son, her only constant in this unfamiliar world of Meath men.

I never knew proper hatred before Cormac’s arrival. Josie’s granddaughter and I had played as equals, conquering foes in the imaginary continent of her back garden. But soon Cormac and I were fighting for real territory, possession of the hearthrug or ownership of Dinky cars and torn comics. He watched me constantly in those first weeks, imitating my every action and discovering my favourite places to play in, then getting there before me. ‘It’s mine, mine, mine!’ Our chorus would bring Phyllis screeching from the kitchen.

It was the same in the schoolyard, where he shadowed me from a distance. Phyllis watched from the gate, making sure I held his hand until the last minute. But once she was gone I let him stew in the stigma of his different accent, refusing to stand up for him when boys asked if he was my new brother. The funny thing was that I had always wanted a brother, but I could only see Cormac as a threat, walking into my life, being made a fuss of by people who should have been making a fuss of me. Previously my father had been away in Dublin a lot, but I’d always had him to myself when he got home. Now Phyllis was there every evening in the hallway before me, perpetually in my way like a puppy dog needing attention. I was put to bed early just so they could be alone and even then I had to share my room with a usurper.

It was more than cowardice therefore that stopped me intervening when Pete Clancy’s gang started picking on Cormac. They were doing my work for me. I would slip away into a corner of the yard and experience a guilty thrill at hearing the distant sounds of him being shoved and kicked. Only when a teacher’s whistle blew would I charge into their midst, always arriving too late to help.

That ruse didn’t stop me being blamed to my face by Phyllis and blamed to my father when he came home from his new offices in Trim, which seemed to have been deliberately set apart from the main Navan Council headquarters. The outhouse lay idle, with his private practice gone. The box-room had been filled with my father’s old records and papers, ever since the morning, some months previously, when Josie and I found the outhouse door forced and the place ransacked. My father had dismissed it as a prank by flyboys from down the town, refusing to phone the police. But that night after Josie was gone Barney Clancy and he had spent hours down there clearing boxes out.

Any extra paperwork at home was done from a new office in the box-room now, though generally he preferred to work late in Trim where he had a small staff under him. News of an outsider being parachuted into this new position – created in a snap vote by councillors at a sparsely attended meeting – had surpassed even his second bride in making him the talk of Navan. Some claimed that the two in-house rivals for the new post had built up such mini-empires of internal support that a schism would have occurred within the planning office had either of them got the job. An honest broker was required, without baggage or ties, to focus on new developments. But others muttered begrudgingly about clout, political connections and jobs being created to undermine the structures already in place.

These whispers went over my head. I just knew that he came home later, seemed more tired and was more prone to snap. Joey Kerwin stopped one Saturday to watch Phyllis’s hips sway into the house ahead of us as though wading through water. ‘You know what they say about marriage, Eamonn?’ he gibed. ‘It’s the only feast where they serve the dessert first!’ My father ushered us in, ignoring the old farmer’s laugh. But sometimes I now woke to hear voices raised downstairs and muffled references to Cormac’s name and mine. Once there was a screaming match halted by a loud slap. One set of footsteps rushed up the stairs, followed some time after by a heavier tread. Then I heard bedsprings and a different sort of cry.

But I experienced no violence, at least not at first. Perhaps the unseen eyes of my mother’s ghost still haunted him from the brighter squares of wallpaper where old photos had been taken down. Once I woke to find him on the edge of my bed watching me. This isn’t easy, you’ve got to help me, son. I didn’t want to help. I wanted Cormac beaten up so badly by Pete Clancy that Phyllis would pack and leave. I wanted my father to myself, like in the old days when we’d walk out along the Boyne or I’d stand beside him as he swapped jokes in shop doorways in the glamorous male world of cigarettes and betting tips. But Cormac merely dug in deeper, accepting Clancy’s assaults with a mute, disarming bewilderment that was painful to watch and was countered by an increasingly strident assertiveness at home. Why can’t I drink from the blue cup? Why does Brendan say it belongs to him? I thought you owned everything now, Mammy? Why can’t I sleep in the proper bed?

Why couldn’t he? The question began to fixate Phyllis. If her own son wasn’t good enough for the best, then, by reflection, neither was she. Why didn’t her new husband take her side? Was it because he did not respect her as much as his first wife who had been the nuns’ pet, educated with the big shopkeepers’ daughters in the local Loreto convent? I can only imagine what accusations she threw at him at night, the ways she found to needle him with her insecurities, the sexual favours she may have withheld – favours not taught in home economics by the Loreto nuns.

I woke one Monday to find two bags packed in the hallway and raised voices downstairs. I pushed the kitchen door open. Startled, my father turned and slapped me. ‘Get out, you!’ I stood in the hallway and stuck my tongue out at Cormac who was spying through the banisters.

My father silently walked me to school that day while Cormac stayed at home. It was the last year before they stopped having the weekly fair in the square, with fattened-up cattle herded in from the big farms at 6 a.m. and already sold and dispatched for slaughter by the time school began. I remember the fire brigade hosing down the square that morning, forcing a sea of cow-shite towards the flooded drains, and how the shite itself was green as if the terrified cattle had already known their fate.

I was happy when nobody came to collect me after school. I walked alone through the square, which shone by now although the stink still lingered from the drains. I didn’t know if anyone would be at home. On my third knock Phyllis opened the door. Her bags were gone from the hall. Cormac was watching television with an empty lemonade bottle beside him. Upstairs, his coloured quilt lay on my bed, his teddies peering through the brass bars at the end. My pillow rested on the smaller camp-bed in the corner. Two empty fertilizer bags lay beside the door, filled to the brim with shredded wallpaper. Scraps of yellowing roses, stems and thorns. On the bare plaster faded adult writing in black ink that I couldn’t read had been uncovered. I changed the beds back to the way they should have been. Then I locked the bedroom door, determined to keep it shut until my father returned home to this sacrilege.

I don’t know how long it took Phyllis to notice that I had not come down for my dinner. Furtively I played with Cormac’s teddies, then stood by the window, watching children outside playing hopscotch and skipping. I didn’t hear her footsteps, just a sudden twist of the handle. She pushed against the door with all her weight. There was the briefest pause before her first tentative knock. Almost immediately a furious banging commenced.

‘Open this door at once! Open this door!’

The children on the street could hear. The skipping ropes and chanting stopped as every eye turned. I put my hand on each pane of glass in succession, trying to stop my legs shaking. Cormac’s voice came from the landing, crying for some teddy on the bed. Phyllis hissed at him to go downstairs. A man with a greyhound pup looked up as he knocked on Casey’s door. Phyllis was screaming now. Mr Casey came out, glanced up and then winked at me. He turned back to the man who held the puppy tight between his legs while Mr Casey leaned over with a sharp iron instrument to snip off his tail. The greyhound howled, drowning out Phyllis’s voice and distracting the children who gathered around to enjoy his distress, asking could they keep his tail to play with.

I desperately needed to use the toilet. I wanted my father to come home. I wanted Phyllis gone and her red-haired brat with her. Lisa Hanlon came out of her driveway, nine years of age with ringlets, white socks and a patterned dress. Watching her, I felt something I could not understand or had never experienced before. It was in the way she stared up, still as a china doll while her mother glanced disapprovingly at Mr Casey and the greyhound and then briskly took her hand. I wanted Lisa as my prisoner, to make her take off that patterned dress and step outside her perfect world.

Then Lisa was gone, along with the man and his whimpering pup. Mr Casey glanced up once more, then went indoors. I had to wee or it would run down my leg. There was a teacup on the chest of drawers, with a cigarette butt smeared with lipstick stubbed out on the saucer. Smoking was the first habit Phyllis had taken up after arriving in Navan, her fingers starting to blend in with the local colour. But I couldn’t stop weeing, even when the teacup and saucer overflowed so that drops spilled out onto the lino.

Phyllis’s screams had ceased. Loud footsteps descended the stairs. I wanted to unlock the door and empty the cup and saucer down the toilet before I was caught, but I couldn’t be sure that she hadn’t crept back upstairs to lie in wait for me. I was too ashamed to empty them out of the window where the children might see. Ten minutes passed, twenty – I don’t know how long. My hand gripped the lock, praying for my father’s return. I had already risked opening the bedroom door when I heard her footsteps ascend the stairs. I locked it again and sank onto the floor, putting the cup and saucer down beside me.

‘Brendan. Open this door, please, pet. You must be starving.’ This was the soft voice she used when addressing Cormac, her Dublin accent more pronounced than when speaking to strangers. ‘Let’s forget this ever happened, eh? It can be our secret. Your dinner is waiting downstairs. Don’t be afraid, I promise not to harm you.’

Sometimes in dreams I still hear her words and watch myself slowly rise as if hypnotized. I try to warn myself but each time the hope persists that she means what she says. Her voice was coaxing, like a snake charmer’s. I turned the key with the softest click. Everything was still as I twisted the black doorknob, which suddenly dug into my chest as she pushed forward, throwing me back against the bed. I tried to crawl under it, but was too slow. She grabbed my hair, dragging me across the lino.

Her shoe had come off. She used the sole to beat me across my bare legs. I thought of Lisa Hanlon and her doll-like body. I thought of Cormac, sitting on the stairs, listening. My foot made contact with her knee as I thrashed out. Phyllis screamed and raised her shoe again, its heel striking my forehead above the eye. I bit her hand and she fell back, knocking over the cup and saucer. From under the bed where I had crawled, I watched a lake of urine slowly spread across the lino to soak into her dress. Even in my terror, something about how she lay with her dress up above her thighs and her breasts heaving excited me. Suddenly I wanted to be held by her, I wanted to be safe. Phyllis slowly drew herself up so I could only see her hands and knees. Cormac’s feet appeared, his thick shoes stopping just short of the puddle.

‘I’ll not mind you!’ she screamed down. ‘You’re worse than an animal. I was free once. I won’t stay in this stinking, stuck-up, dead-end, boghole of a town, not for him or any of yous!’

She was crying. I felt ashamed for her, knowing that the children on the street could hear. Cormac stood uselessly beside her. ‘Can I get my teddy now, Mammy?’

I closed my eyes, dreading my father’s return home. The lake of urine had almost reached me. I could smell it, as I pressed myself tight against the wall, but soon it began to seep into my jumper. My temple ached from the impact of her shoe. My legs stung where she had beaten them. When I opened my eyes Phyllis and Cormac were gone.

Dublin – the most ungainly of capital cities, forever spreading like chicken pox. A rash of slate roofs protruded from unlikely gaps along the motorway. Cul-de-sacs crammed into every niche, with curved roads and Mind Our Children signs. Watching from the bus it was hard to know where Meath ended and the Dublin county border began. Or at least it would have been for somebody whose father hadn’t virtually ruled a small but influential sub-section of the planning department within Meath County Council.

Dunshaughlin, Black Bush, Dunboyne, Clonee. Every field and ditch in every townland seemed to be memorized in my father’s head. Each illegally sited septic tank, every dirt road on which some tiny estate appeared as if dropped from the sky, with startled city children peering into fields that bordered their rubble-strewn back gardens. He knew every stream piped underground and the ditches where they resurfaced as if by magic. Within a couple of years he had become Mr Mastermind, able to track in his head the labyrinth of shell companies that builders operated behind, and willing, if necessary, to pass on their home phone numbers to residents’ groups wondering whatever happened to the landscaping that had looked so inviting in the artist’s impression in their advance brochures.

Fifteen years ago these townlands had seemed like a half-finished quilt that only he understood the pattern for. But by the time he retired surely not even my father could have kept track of the chaotic development that made these satellite towns resemble a box of Lego carelessly spilled by a child. Builders from Dublin, Meath, Kildare, Northern Ireland and the West vying with each other for the smallest plot of land. Men who once spat into palms in my father’s outhouse to seal deals to build lean-tos and cowsheds, were now rich beyond their imagination. The sands of their retirements would be golden were it not for the tribunals into corruption currently sitting in Dublin Castle to investigate hundreds of frenzied re-zoning motions by councillors against County Development Plans around Leinster.

The new motorway petered out at the Half Way House pub, beside the old Phoenix Park racecourse which had mysteriously burnt down. I was back among familiar Dublin streets, with chock-a-block traffic being funnelled down past my old flat in Phibsborough. The bus crawled past an ugly triumphalist church, then onto the North Circular Road, before turning down Eccles Street. The driver stopped to drop off a girl with two bags and I slipped away too.

It was 7 p.m. Visiting time at the Mater Private Hospital across the road. A discreet trickle passed through the smoked-glass doors into a lobby that looked like a hotel, with plush sofas and soft piped music. I could never pass such buildings without remembering how we tried to nurse Miriam’s dying mother in her rented house at the Broadstone.

An elderly man in a black leather jacket leaned on a crutch beside the railings, so circumspect that from a distance you wouldn’t know he was begging. He had my father’s eyes. The older I got the more I found that old beggars always had, staring up slyly as if only they could recognize me. I slipped a coin into his hand and walked past, up the street to where people streamed towards the huge public hospital, with cars and taxis competing for space outside. The open glass doors drew me towards them. I scanned the lists of wards with saints’ names and quickly wagered on Saint Brigid’s, then leaned over the porter’s desk before I lost my nerve.

‘Brogan?’ I asked. ‘Have you a Mrs Phyllis Brogan here?’

He checked his list, then scrutinized me. ‘You’re not a journalist?’

‘No.’

‘Family?’

‘An old acquaintance.’

‘Second floor, Saint Martha’s ward.’

I cursed myself, having wanted to change my bet to Saint Martha’s, but the first rule in any gambling system was never to switch once a choice was made. A familiar stab of self-disgust swamped me, though it was only a wager in my mind. For two years I had managed to avoid placing a bet, except for the dozens of imaginary ones that I tortured myself with daily.

‘Do you get many journalists?’ I enquired.

‘Just one from a tabloid and some bogman who became aggressive. Her daughter-in-law asked us to keep a check. It’s distressing, in the woman’s condition.’

I noted how Miriam had made the arrangements and not Sarah-Jane. The porter was directing me towards the lift.

‘I’m just waiting for my brother,’ I lied. ‘He’s getting flowers. We said we’d go up together.’

It was the first excuse to enter my head. He nodded towards the sofas. It felt strange to be under the same roof as Phyllis, but I needed to ensure that she was out of the way and hadn’t moved back home. I picked up an Evening Herald somebody had left on the sofa. Romanian Choir Hoax, the headline read. Organizers of a choral festival in Westport were left red-faced today after the thirty-five-strong Romanian choir they invited into Ireland turned out to be bogus. While a two-hundred-strong audience waited in Westport church, the alleged singers took taxis from the airport to join the queue of illegal immigrants seeking asylum outside the Department of Foreign Affairs. I pretended to read on, awaiting a chance to slip away when the porter left his desk.

It was a more comfortable wait than others I had known involving Phyllis. The eternity of that evening I spent as a child soaked in urine beneath my bed came back to me. Afraid to venture out, even after Phyllis went sobbing downstairs, with Cormac like a dog behind her. Teatime came and the playing children were called in, their skipping ropes stilled and the silence unbroken by the thud of a ball. Afterwards nobody ran back out as usual, still clutching their bread and jam. It felt like the whole street was awaiting the judgement of my father’s car.

Finally he arrived home. The car engine was turned off and the front door opened. I expected screaming from Phyllis, but it was so quiet that I prayed she had left. Then my father ascended the stairs, his polished shoes stopping short of the pool of urine. He sat on the camp-bed so that all I could see were his suit trousers.

‘Come out.’

‘I’m scared.’

‘I’m not going to hit you.’

I clambered stiffly out, my clothes and hair stinking of piss. ‘I want my wallpaper back,’ I said. ‘I’ve always had it.’

‘You’ll speak when I tell you to. Your mother says you threw wee over her.’

‘She’s not my mother.’

The slap came from nowhere. I didn’t cry out or even lift a hand to my cheek.

‘If she doesn’t become your mother then it will be your choice. This isn’t easy for any of us. Since she arrived you’ve done nothing but cause trouble. I’ll not come home to shouting matches. This is my wife you’re insulting. She doesn’t have to keep you. Did you think of that? When I was growing up I never saw my older half-sister. She was farmed out back to her mother’s people up the Ox Mountains when Daddy’s first wife died. That was the way back then. My own mother had enough to be doing looking after her own children without raising somebody else’s leavings. Few women would take on the task of raising a brat like you. Because that’s what you’ve become. You understand? If you don’t want a mother then try a few nights without one. Go on, take those fecking blankets off the precious bed that you’re so fond of. This is a family house again and you can roost in the outhouse until you decide to become one of us.’

Even when he repeated the instructions they still didn’t register. My father had to bundle the blankets up into my arms before I started moving. I could hardly see where I was going. The stairs seemed endlessly steep in my terror of tripping. The hallway was empty. In the kitchen Cormac sat quietly. There was no sign of Phyllis. Eighteen steps brought me to the door of the outhouse. My father walked behind me, then suddenly his footsteps weren’t there. I undid the bolt, then looked back. He had retreated to watch from the kitchen doorway, framed by the light. I couldn’t comprehend his expression. A blur ofblue cloth appeared behind him. Phyllis hung back, observing us. He closed the door, leaving me in the gloom.

I turned the light on in the outhouse and looked around. Anything of value had been removed to the box-room after the break-in some months before. The place had become a repository for obsolete items like the two rusty filing cabinets – one still locked and the other containing scraps of old building plans, a buckled ruler and a compass. Among the old copies of the Meath Chronicle in the bottom drawer I found a memorial card for my mother, her face cut from a photo on Laytown beach. One pane of glass in the wall was cracked. The other had been broken in the break-in and was replaced by chicken wire to keep cats out. The darkness frightened me, yet I turned the light out again, wanting nobody on the street to know I was there.

Casey’s kitchen window looked bright and inviting. The back of our own house was in darkness, but I knew The Fugitive was on television in the front-room, with Richard Kimble chasing the one-armed man. Cormac would be lying there on the hearthrug, savouring every moment of my favourite programme.

I listened to the beat of a tack hammer from the lean-to with a corrugated roof, built against the back wall of Casey’s house. It was answered by other tappings from other back gardens, like a secret code. The official knock-off time marked the start of real work for most of our neighbours who worked in the town’s furniture factories. They rushed their dinners so they could spend each evening working on nixers, producing chairs and coffee tables, bookcases or hybrid furniture invented by themselves. Sawdust forever blew across the gardens, with their tapping eventually dying out until only one distant hammer would be left like a ghost in the dark.

Hanlon’s cat arched her back as she jumped onto our wall, then sprang down. I miaowed softly but she stalked past. A late bird called somewhere and another answered. The back door opened. My father appeared with a tray. I hunched against the wall. He entered and stood in the dark, not wanting to put the light on either.

‘Bread and cheese,’ he said. ‘And you’re lucky to get it.’

‘When can I come in?’

‘Not tonight.’

‘Has he got my bed?’

‘He has a name. My wife decides who sleeps where from now on.’ He put down the tray and stood over me. ‘Don’t make me have to choose, Brendan. If you do you’ll lose.’

‘I hate her. I want them to go.’

‘She’s going nowhere, Brendan. I’ll make this family work if it kills me. A man needs a wife. I can’t mind you alone. You understand?’

I didn’t reply and he didn’t expect me to. He sat on the edge of his old desk for what seemed an eternity. Perhaps he was the most lost of us all that night, torn between desire and guilt, remembering simpler times when he was fully in control, the monarch of this makeshift office. I just know that I never felt so close to him again as during that half-hour when he sat as if turned to stone, until Phyllis’s voice finally called from the kitchen.

‘Make yourself a bed,’ he said. ‘Let’s have no fuss.’

As he stood up his hands fiddled with something in the dark. When he opened the door I saw in the half-light how he had removed his belt and held it folded in half. I watched through the chicken wire as he walked up the path, elaborately running the leather belt back through his trouser loops and fixing the buckle as she watched. He nodded to her. They went in and I heard the heavy bolt on the kitchen door.

The glass doors opened in the hospital foyer. An ambulance, with its siren turned off and blue light flashing, had pulled up outside. The porter disappeared through a doorway while staff bustled about, allowing me to slip away unnoticed. The beggar was gone. I crossed Dorset Street – a blocked artery of Dublin which had always refused to become civilized. Shuttered charity shops and gaudy take-aways. Pubs on every corner, alleys leading down to ugly blocks of flats. People walked quickly here, trying to look like they knew where they’re going.

Where was I heading, with just two bags waiting for me in a luggage locker at the bus station? But what other sort of homecoming had I any right to expect? I was putting more than just myself at risk by being here, but even without my father’s murder I always knew that one day I would push the self-destruct button by turning up again.

I crossed into Hardwick Street and passed an old Protestant church that seemed to have become a dance club. Across the road a tall black girl stood at a phone box, smoking as she spoke into the receiver. I don’t think she saw the two Dublin girls emerge through an archway from the flats, with a stunted hybrid of a fighting dog straining on his lead. At first I thought they were asking her for a light, until I saw the black girl’s hair being jerked back. She screamed. I stopped. There was nobody else on the wide bend of footpath. Music blared from a pub on the corner. Two lads came out from the flats as well, as the black girl tried to run. The Dublin girls held her by the hair as the youths strolled up.

‘Nigger! Why don’t you fuck off back home, you sponging nigger!’

There were four of them, with the dog terrifying their victim even further. One youth grabbed her purse, scattering its contents onto the ground – keys, some sort of card, scraps of paper and a few loose coins which they ignored. They weren’t even interested in robbing her. I knew the rules of city life and how to melt away. But something – perhaps the look in the black girl’s eyes, which brought back another woman’s terror on a distant night in this city – made me snap. I found myself running without any plan about what to do next, shouldering into the first youth to knock him off balance.

I grabbed the second youth around the neck in a headlock, twisting his arm behind his back. The girls let go their victim in surprise, while the dog circled and barked, too inbred and stupid to know who to bite. The black girl leaned down, trying to collect her belongings from the ground.

‘Don’t be stupid, just run, for God’s sake, run!’

‘Don’t call me stupid!’ she screamed at me, like I was her attacker. One girl swung a hand at her, nails outspread as if to claw at her eyes. The black girl caught the arm in mid-flight, sinking her teeth into the wrist. The first youth had risen to leap onto my back, raining blows at my face as I fell forward, crushing the youth I was still holding. I heard his arm snap as he toppled to the ground. He screamed as the first youth cursed.

‘You nigger-loving bastard! You cunt!’

My forehead was grazed where it hit the pavement, with my glasses sliding off. Their aggression was purely focused on me now, although the second youth was in too much pain to do much. I heard running footsteps and knew that I was for it. But when the thud of a boot came it landed inches above my head. The youth on top of me groaned and rolled off. I heard him pick himself up and run away. The other youth broke free, limping off with the shrieking girls following.

Only now did the dog realize that he was meant to attack us. I sensed him come for me and raised my arms over my face. His teeth had brushed my jacket when I heard a thump of a steel pole against his flank. He turned to snarl at his attacker as somebody pulled me up. It was a tall black man, around thirty years of age. The black girl knelt beside us, crying, cramming items into her purse. A smaller, stockier black man banged a steel pole along the concrete, holding the dog off. The black girl turned to me.

‘Don’t you call me stupid! Don’t you ever!’

‘Stop it, Ebun,’ the man holding me said. He looked into my face. ‘E ma bínú. Can you walk?’

‘Just give me a second.’

‘We haven’t got a second. More of your sort will be back.’

‘They’re not my sort.’

‘They’re hardly mine.’ He bent down to retrieve my glasses from the ground. ‘You should get out of here. Have you a car?’

‘No.’

‘Where do you live?’

‘Abroad.’

‘Where are you staying then?’

‘I don’t know yet. Somewhere.’

The girl, Ebun, looked over her shoulder towards the windows of the flats. ‘He’s the one who’s stupid,’ she said. ‘He jumped right in.’

With a final snarl the dog loped off back towards the entrance. There was a shout from a stairwell. I knew they wanted to get away from there.

‘He’d better come with us,’ the man told Ebun.

She answered in a language I couldn’t understand. My courage had vanished now that the fight was over, I was unsure if my legs would support me.

‘I know,’ the man replied. ‘But we can’t leave him here.’

The stockier man put the steel pole back inside his coat. Arguing in their own language, they half-led and half-carried me back onto Dorset Street, past a row of rundown shops and around the corner into Gardner Street. Their flat was at the top of a narrow Georgian house, with wooden steps crumbling away and rickety woodwormed banisters. I had once haunted the warrens of bedsits around here, knowing every card school in the anonymity of flatland where one could sit up all night to play poker and smoke dope.

But the journey up the stairs now had a dream-like quality. Every face that appeared on each landing was black or Eastern European. I had spent a decade abroad, but somehow in my mind Ireland had never changed. Maybe they didn’t hang black people in Navan for being the Devil any more, but before I left the occasional black visitor was still a novelty, a chance to show our patronizing tolerance which distinguished us from racist Britain. We had always been an exporter of people, our politicians pleading the special case of illegal Irish immigrants living out subterranean existences in Boston and New York. So, with our new-found prosperity, why did I not expect the boot to be on the other foot? Ebun unlocked a door and they helped me onto a chair in their one-room flat. She put some ice from the tiny fridge into a plastic supermarket bag. Kneeling beside the chair she held it against my forehead.

‘To keep the swelling down,’ she said. ‘You were crazy brave. I should not have shouted at you.’

‘I didn’t mean to call you names. I just wanted to make you run.’

‘I don’t run,’ she said. ‘No more running. I see too much to run any more.’

The men talked in low voices in their own language. Another man joined them, staring at me with open curiosity. I tried to stand up, wanting to escape back down onto the street. These damp walls reminded me too much of things I had spent a lifetime fleeing. I wondered at what time the bus station closed.

‘Where are you going?’ Ebun pushed me back. ‘You have been hit. You must rest.’ She adjusted the ice-pack slightly.

‘He saw everything,’ the stocky man said. ‘I know those kids. This time we have a witness. I say we call the police.’

‘No,’ I said quickly. ‘I can’t.’

‘Can’t what? Go against your own kind?’

‘It’s not that.’

‘Leave him alone,’ Ebun said. ‘What’s the use of a court case in six months’ time? By then we could have all been put on a plane back to Nigeria. Besides, a policeman anywhere is still a policeman. We should never trust them.’

‘We thank you for your help,’ the man who had picked me up said. ‘This should not have happened. I tell my sister not to go out alone, but do you think she listens? Have you eaten?’

‘No.’

‘We have something. It is hot.’

I had smelt the spices when I entered the flat. The stocky man went to the cooker and ladled something into a soup dish. ‘E gba,’ he said, handing me what looked like a sort of oily soup. ‘It is called egusi. My name is Niyi.’ He smiled but I knew he was uneasy with my presence. Ebun removed the ice-pack and they talked among themselves as I ate. Finally her brother approached.

‘Tonight you have nowhere to stay?’

‘Nowhere arranged as yet.’

‘Then we have a mattress. You are welcome.’

I had enough money for a hotel. I was about to say this when I looked at Ebun’s face and the still half-antagonistic Niyi. Strangers adrift in a strange land, refugees who had left everything behind, who lived by queuing, never knowing when news would come of their asylum application being turned down. This flat was all they possessed.

‘I would be grateful,’ I replied.

‘Lekan ni oruko mi. My name is Lekan.’ He held his hand out. I shook it.

‘My name is Cormac,’ I lied, with the ease of ten years’ practice.

Lekan led me across the landing to a small bathroom. The seat was broken on the toilet, which had an ancient cistern and long chain. I washed my face, gazing in the mirror at my slightly grazed forehead. Then I peered out of the small window: rooftops with broken slates, blocks of flats in the distance, old church spires dwarfed by an army of building cranes, the achingly familiar sounds of this hurtful city.

A few streets away the woman I had been taught to call ‘Mother’ lay dying in hospital. Out in the suburbs beyond these old streets the woman I had once called ‘wife’ lived with the boy who once called me ‘Father’. Conor’s seventeenth birthday was in two months’ time, yet he lived on in my mind the way he had looked when he was seven.

On the landing the Nigerians were bargaining in a language I could not understand and then in English as they borrowed blankets to make up a spare bed. My forehead hurt. Everywhere my eyes strayed across the rooftops brought memories of pain, so why was my body swamped by the bittersweet elation of having come home?