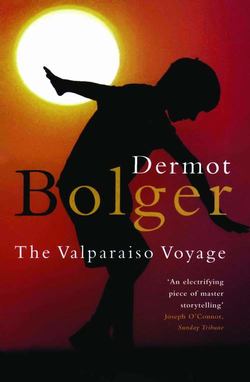

Читать книгу The Valparaiso Voyage - Dermot Bolger - Страница 8

II SUNDAY

ОглавлениеAsofa with scratched wooden arms that probably even looked cheap when purchased in the 1970s; a purple flower-patterned carpet; one battered armchair; a Formica table that belonged in some 1960s fish and chip shop; an ancient windowpane with its paint and putty almost fully peeled away. I woke up on Sunday morning in Ebun’s flat and felt more at home than I had done for years.

A solitary shaft of dusty light squeezed between a gap in the two blankets tacked across the window as makeshift curtains. It fell on Niyi’s bare feet as he sat on the floor against the far wall watching me. He nodded, his gaze not unfriendly but territorial in the way of a male wary of predators in the presence of his woman.

I looked around. One sleeping-bag was already rolled up against the wall. Ebun occupied the double bed, her hair spilling out from the blankets as she slept on, curled in a ball. Niyi followed my gaze. Maybe he had just left the double bed or perhaps the empty sleeping-bag was his. I’d no idea of where anyone had slept. All three Nigerians had still been talking softly when I fell asleep last night.

‘Lekan?’ I enquired in a whisper.

‘Gone. To help man prepare for his appeal interview, then to queue.’

‘What queue?’

‘Refugee Application Centre. He needs our rent form signed.’

‘But it’s Sunday?’

‘On Friday staff refuse to open doors. They say they frightened by too many of us outside. Scared of diseases I never hear of. By Monday morning queue will be too long. Best to start queue on Sunday afternoon, and hope that when your night-clubs finish there is less trouble with drunks. Lekan does not like trouble.’

‘How will he eat?’

Niyi shrugged. ‘We bring him food. Lekan is good queuer. I only get angry. Too cold. Already I am sick of your country.’

He pulled a blanket tighter around him. We had been whispering so as not to wake the girl. It was seven-twenty on my watch. There would be nowhere open at this time in Dublin, not even a café for breakfast. I turned over. My pillow was comfortable, the rough blanket warm. My limbs were only slightly stiff from the thin mattress. I could go back asleep if I wished to. From an early age I had trained myself to fall asleep anywhere.

Not that this ability was easily learned. I spent five years sleeping in the outhouse as a child, yet the first few nights, when I barely slept at all, remain most vivid in my mind. My terror at being alone and the growing sensation of how worthless and dirty I was. Throughout the first night I was too afraid to sleep. I knelt up on the desk to watch lights go out in every back bedroom along the street. My father’s light was among the first. Yet several times during the night I thought I glimpsed a blurred outline against the hammered glass of the bathroom window. I didn’t know whether it was my father or a ghost. But someone seemed to flit about, watching over me or watching that I didn’t escape.

I’d never known how loud the darkness could be. Apple trees creaking in Hanlon’s garden, a rustling among Casey’s gooseberry bushes. Paws suddenly landing on the outhouse roof. Footsteps – real or imagined – stopping halfway down the lane. Every ghost story I had ever heard became real in that darkness. Dawn eventually lit the sky like a fantastically slow firework, and, secure in its light, I must have blacked into sleep because I woke suddenly, huddled on the floor with my neck stiff. My father filled the doorway.

‘School starts soon. You’d better come in and wash.’

He didn’t have to tell me not to mention my night in the outhouse at school. Instinctively I understood shame. Cormac sat at the kitchen table. He didn’t seem pleased at his victory, he looked scared. Phyllis refused to glance at me. She placed a bowl of porridge on the table, which I ate greedily, barely caring if it scalded my throat.

‘Comb his hair,’ my father instructed her. ‘He can’t go looking like he slept in a haystack.’

But the tufts would not sit down, no matter how hard Phyllis yanked at them. Finally she pushed my head under the tap, then combed the drenched hair back into shape. Her fingers trembled, her eyes avoiding mine. She snapped at Cormac to hurry up, pushing us both out the door. We were late, trotting in silence at her heels. Lisa Hanlon stared at me as she passed with her mother. Phyllis took my hand, squeezing my fingers so tightly that they hurt. Every passer-by seemed to be gazing at me and whispering.

‘You mind your brother this time.’ Her hiss was sharp as she joined our hands together, pushing us through the gate. We walked awkwardly towards the lines of boys starting to be marched in.

I glanced at Cormac whose eyes were round with tears. ‘If you slept in my bed I’ll kill you, you little gick,’ I whispered. He released his hand from mine once Phyllis was out of sight.

It was hard to stay awake. My eyes hurt when I rubbed them. I avoided Cormac at small break, while a boy jeered at me in the long concrete shelter: ‘What was your mother screaming about yesterday?’

‘She’s not my mother.’

Cormac moved alone through the hordes of boys, being pushed by some who stumbled into his path. But he seemed content and almost oblivious to them, absorbed in some imaginary world. I watched him walk, his red hair, his skin so white. He was the only boy I knew who washed his hands at the leaky tap after pissing in the shed which served as a school toilet. At that moment I wanted him as my prisoner too, himself and Lisa Hanlon with tied hands forced to do my bidding on some secret island on a lake in the Boyne. I don’t know what I really wanted or felt, just that the thought provided a thrill of power, allowing me to escape in my mind from my growing sense of worthlessness.

When lunchtime came I knew Cormac was about to get hurt. Bombs were exploding in the North of Ireland, with internment and riots and barbed wire across roads. I didn’t understand the news footage that my father was watching so intently at night. But Pete Clancy’s gang had started to jeer at Cormac, chanting ‘Look out, here comes a Brit’ and talking as though the British army was a private militia for which he was personally responsible.

Yet I had never heard him mention his father or living in Scotland. It was like he had no previous existence before gatecrashing my life in Navan. He spoke with a softer version of his mother’s inner-city Dublin accent, but this made no difference to Pete Clancy, who detested Dubliners anyway. Cormac was the nearest available scapegoat and therefore had to suffer the consequences.

I watched from the shed as a circle of older boys closed in on him, while younger lads ran to warn me that he was in trouble. The prospect of violence spread like an electric current through the yard. I wanted Cormac hurt, yet something about his lost manner made me snap. The huddle of boys seemed impenetrable as they scrambled for a look. They let me through as if sensing I meant business. But even if I could have helped him I had left it too late. Cormac’s shirt was torn, his nose a mass of blood. Pete Clancy stopped, knowing he had gone too far. Behind him Slick McGuirk and P. J. Egan stood like shadows, suddenly scared. Slick was trembling, unable to take his eyes off Cormac, maybe because when they had nobody else to torment the two companions always tormented him. Pete Clancy let go of Cormac’s hair and all three stepped back, leaving him kneeling there.

The circle was dispersing, voices suddenly quiet. I knew Mr Kenny was standing behind me, the tongue of a brass bell held in his left fist and his right hand clenching a leather strap with coins stitched into it. He looked directly at Pete Clancy. ‘What’s been going on here?’

‘Two brothers, a Mháistir, they were fighting.’

Clancy’s eyes warned me about what could happen afterwards if I contradicted him. McGuirk and Egan took his lead, staring intimidatingly at me.

‘Did you try to stop them, Clancy?’

‘I tried, a Mháistir.’

The Low Babies and High Babies were sharing a single classroom that year, while the leaky prefab, which previously housed two classrooms, was being demolished to make room for a new extension. Every boy knew that the school would never have leapfrogged the queue for grant aid if Barney Clancy hadn’t pulled serious strings within the Department of Education. My father might be respected but my word held no currency against a TD’s son. I looked at Pete Clancy’s closed fist which still held a thread of Cormac’s hair.

‘Is this true, Brogan?’ Mr Kenny asked me.

‘No, sir. He’s not my brother.’

Someone sniggered, then went silent at the thud of Mr Kenny’s leather against my thigh. The stitched coins left a series of impressions along my reddened flesh.

‘Don’t come the comedian with me, Brogan!’

It was hard to believe that two hundred boys could be this quiet, their breath held as they anticipated violence being done to somebody else. Pete Clancy eyed me coldly.

‘Did you strike this boy?’ Mr Kenny asked me again.

Cormac looked up from where he knelt, trying to wipe blood from his nose. ‘No, he didn’t.’

‘I did so!’ I contradicted him, not knowing if I was trying to save Cormac or myself or us both. Clancy’s henchmen haunted every lane in Navan, whereas with Kenny it would simply be one beating. ‘He’s a little Brit,’ I said, parroting Clancy’s phrases. ‘They’re only scum over there in Scumland.’

‘Brendan didn’t touch me, sir,’ Cormac protested. ‘Please leave him alone.’

‘Stand up,’ Kenny told him. Cormac rose. I knew he was crazy, only making things worse. But Clancy and the others stepped back, suddenly anxious. Cormac’s honesty was illogical. There was no place for it in that schoolyard and they were suddenly scared of him as if confronted by somebody deformed or spastic.

‘You needn’t be afraid of what he’ll do to you at home. I’ll make sure your mother knows about this,’ Mr Kenny said, beckoning us to follow him.

A large wooden crucifix dominated the corridor outside the head brother’s office, framed by a proclamation of the Republic and a photo of a visiting bishop at confirmation time. I stood outside the office while Slick McGuirk and P. J. Egan pressed their faces against the window on their way home, muttering, ‘You’re dead, fecking dead!’

Their threats weren’t directed at Cormac sitting on a chair near the statue of Saint Martin de Pours, but at me. They ignored the child who had defied them, but, in acquiescing, I had become their new bait.

Phyllis didn’t even glance at me when she emerged from the head brother’s office. Her silence lasted all the way home as she gripped Cormac’s hand and I fell back, one step, two step, three steps behind them. Conscious of watching eyes and sniggers. Aware of hunger and of how my palms stung so badly that I could hardly unclench my knuckles after my caning by the head brother. Cormac didn’t speak either. Perhaps he realized that the truth was of no use or maybe he was exacting revenge for every sly pinch I’d ever given him.

The grass needed a final autumn cut in the back garden. I remember that leaves had blown in from the lane to cover the small lawn with a riot of colour. They looked like the sails of boats on a crowded river. I wanted nothing more than to block the real world out by kneeling to open my bruised hands and play with them.

‘Tháinig long ó Valparaiso, Scaoileadh téad a seol sa chuan…’

I remembered Brother Ambrose’s voice in class a few weeks before, losing its usual gruffness and becoming surprisingly soft as he seduced us with a poem in Irish about a local man who sees a ship from Valparaiso letting down its anchor in a Galway bay and longs in vain to leave his ordinary life behind by sailing away on it to the distant port it had come from.

Phyllis had left us alone in the garden. I knelt to gather up a crinkled fleet of russet and brown leaves and cast them adrift. Cormac watched behind me, then knelt to help by sorting out more leaves and pushing them into my hands.

‘What are they?’ he asked.

‘A fleet of ships. Sailing across the world to Valparaiso.’

‘Where’s that?’

‘Somewhere that’s not here.’

He nodded companionably as if the confrontation in the schoolyard had finally given us something in common. It was the first time we became absorbed in playing together, our hands sorting out the leaves excitedly.

‘The purple ones can be pirates,’ he suggested, ‘slaughtering the goody-goody ones that are brown.’

‘Did you come from Scotland on a ship?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘What was it like, Scotland?’

‘I don’t know.’

Footsteps made us turn. Phyllis was struggling with a spare mattress she had taken down from the attic, trying to force it out the kitchen door. Mutely we watched her haul it down the path. My blankets were already in the outhouse from last night. I have a memory of Cormac and I holding hands as we stood together. But this couldn’t be possible, because when she ordered me into the outhouse I was still clutching a pile of leaves tightly in both fists.

‘Put those down before you litter the place,’ she said. ‘Make a bed for yourself. I’ll not have a thug under the same roof as my son.’

Her make-up was streaked from tears. I didn’t want to simply drop the leaves. Cormac opened his hands and I passed them to him so that he could continue the game. He was still holding them, solemn-faced, when Phyllis slammed the door.

I don’t know at what hour my father came home, but it was long after the chorus of wood saws and the tic-tic-tic of upholstery tacks had died out in the garden sheds. He brought down a tray with water and a bowl of lukewarm stew. I told him the truth about Pete Clancy, crying my eyes out, desperate for someone to believe me. The terrible thing is that I think he did believe me, but just couldn’t afford to admit it to me or to himself.

Barney Clancy had dominated that outhouse on every occasion he stood there. His rich cigar smoke, the shiny braces, the shirts he was rumoured to have specially made in Paris. After years of hard times Clancy was putting Navan on the map. Without him there would be no Tara mines or queue-skipping for telephones or factories set up to keep the 1950s IRA men out of mischief. The new wing for Our Lady’s Hospital would not have been built, nor the Classical School resurrected from the slum of Saint Finian’s, and the promise of a municipal swimming pool would have remained just a promise.

Dynasties like the Fitzsimons, Wallaces and Hillards were among the decent honest politicians who would be easily elected for generations to come, but Barney Clancy was different from them and dangerous and special. People talked as if the River Blackwater would stop flowing into the Boyne below the town if he was not there like some Colossus to watch over us. Things were happening to Navan that the aborigines of Kells or Trim could only have wet dreams about. And my father played his part too, not just helping out with constituency matters but increasingly looking after domestic finance and bills and other mundane matters that Clancy no longer had time for. He was respected in the town as a lieutenant to the whirlwind whose audacity was making us the envy of Ireland.

‘I want no more trouble,’ my father said quietly when I finished crying. ‘If and when your mother forgives you you will come back in and stop behaving like a brat.’

He slipped me an old comic from his pocket as he left. It was crumpled and I’d read it a dozen times before. But I studied every word repeatedly to keep the darkness away. Dennis the Menace and the Bash Street Kids. I spoke their lines aloud, imagining myself at one with them for whole moments inside each story, caught up within their anarchic freedom. Then I’d reach the final page and sounds from the street intruded into my loneliness. Toilets flushing, canned laughter from television sets, a woman throwing tea leaves out the back door and banging the empty pot three times like a code.

After undressing I lay in the dark. I thought of Cormac’s white skin snuggled against mine as sleep overcame us on our ship with billowing sails of autumn leaves, which we had steered out along the Boyne to the open sea to sail towards Valparaiso.

Time is not a concept any child can properly understand. One night can last an eternity while several years fuse into a blur. Did my father and Phyllis decide on that first night to permanently exile me, or did my punishment simply become a habit, a decision they never got around to reversing? Maybe they rowed for months over it or perhaps my father simply let Phyllis get on with running the house. He was too swamped by internal County Council sniping with the main planning department and his recently acquired voluntary weekend role of trying to balance the household books of Barney Clancy so as to leave the great man free to focus on politics.

I once overheard my father tell Phyllis about Barney Clancy’s advice to a businessman moving to Athlone. ‘Make them sit up and quake in their boots at the sight of you. Look down your nose on every last Westmeath bog-warrior. Fear is the only way to get Athlone people to respect you.’ Respect. The word rankled with Phyllis, gnawing at her dreams like a cancer. She craved respect in the same way as women in Navan had started yearning to entertain at home with steak fondue evenings or to take foreign holidays that didn’t involve pilgrimages or fasting.

But the hardchaw Dublin workmen erecting a new fluorescent sign over O’Kelly’s butcher’s in Trimgate Street instinctively recognized one of their own as they wolfwhistled after her every morning, and other mothers at the school gate kept a clannish distance. Phyllis mimicked their accents, despising what she regarded as their bog fashions, headscarves and plump safely-married figures that were ‘beef to the heel like a herd of Meath heifers’. Yet she clung to any casual remark addressed to her, desperate for some sign of acceptance.

Back then neighbours counted how many tacks a man used to upholster an armchair, knew if the postman delivered a brown Jiffy bag from England or whose wife was spied visiting a chemist shop in an outlying town. It must have been obvious, even to Phyllis, that people knew and disapproved of my growing ostracism at home. Children from first marriages were sometimes treated as second-class citizens within Irish families, but never to this extreme. Furthermore, for all her airs, I was still a local and they regarded Phyllis as just a blow-in, tarting herself up like a woman on the chase for a husband instead of one securely married.

But the more they ignored her the more I bore the brunt of her frustration. Each day I came home from school, ate dinner at the same table as Cormac and was banished to the shed before she produced ice-cream for his dessert from the new refrigerator which gave itself up to convoluted multiple orgasms every few hours. When my father eventually arrived home he was sent down to harangue me over my latest alleged insult to his wife – Phyllis having abandoned the pretence of me calling her mother.

Some nights he lashed out at me with a fury that – even at the age of ten and eleven – I knew had little to do with my ‘offence’ or even the inconvenience of my existence. At such moments he became like a savage, needing to dominate me because I was the last thing he could control with life starting to spin beyond him. I’d seen him taunted on the street as ‘Clancy’s lap-dog in the Council’ and heard Pete Clancy’s joke about his father taking my father and Jimmy Mahon for a slap-up meal where he ordered steak and onions and when the waiter enquired, ‘What about the vegetables, sir?’ Clancy replied, ‘They can order for themselves.’

The only place where he still felt in command was the outhouse, in which he began to lock papers away in the filing cabinet again, warning me never to mention them to Phyllis. This made me suspect that they were related to my mother, photographs or other souvenirs of her unmentionable absence. Feeling that I was in the same room as them gave me a certain comfort at night.

Mostly, however, he didn’t hit me. After some half-hearted shouting he simply smoked in silence or questioned me about school, joking about the soft time pupils had now compared to his youth. ‘You’re happier down here with your bit of space,’ he observed once, more to himself than me. ‘Few boys your age have so much freedom.’

Often it felt like he was putting off his return back up to the rigid game of happy families being orchestrated in that house. Mama Bear, Dada Bear and room for only one Baby Bear. ‘She’s a good woman,’ he remarked after a long silence one night. ‘It’s not easy for her in this town.’ He looked at me as if wanting a reply, like he ached for reassurance or justification. Yet I knew he was so wound up that if I opened my mouth his fists would fly.

Some evenings I peered through the chicken wire to watch them play their roles in the sitting-room window. Except that nobody seemed to have told Cormac the plot. He had sole possession of the hearthrug and bedroom, but increasingly he wore the distant look I had first seen in the schoolyard. Self-absorbed, no longer clinging to his mother but largely ignoring them by escaping into his own inner world. He seemed the only one of us not to be bent and twisted like a divining rod by unseen tensions.

With the mines creating an influx of jobs, boom times were hitting Navan. Building sites sprang up. Anxious developers, farmers with land to sell and total strangers would call to the house at all hours, hoping in vain for a quiet word with my father after having no joy with the main planning department. Phyllis had instructions to run people like Slab McGuirk from the door, savouring her status at being able to exclude prominent citizens which made her feel as omnipotent as a doctor’s wife or priest’s housekeeper. Very occasionally she attended sod-turnings and ribbon-cuttings with my father if there was a slap-up meal later in the Ard Boyne Hotel or Conyngham Arms in Slane. A girl was paid to babysit Cormac on those occasions, while I was allowed up into the house, for the sake of appearances.

But the outings were rarely a success. The tension was so electric on their return that the babysitter was barely gone before the rows started. ‘What are you sulking about now?’ she would nag in a tipsy voice. ‘How I held my wineglass or laughed too loud or upstaged Clancy’s pig of a wife – the only woman in Navan who doesn’t know about his mistress in Dublin?’ Phyllis’s voice followed me, spoiling for a fight, as I was dispatched to the shed: ‘Come on! Tell me to start behaving like a grown woman. But you like me as a girl when it suits you, don’t you eh, Mr Respectable?’

I was eleven on the night when they grew so caught up in their row – which now seemed almost like a ritualized game leading to subsequent peace-offerings – that they forgot to properly close the bedroom curtains. The gap was small where they shifted in and out of the light. My father was naked, with black hair down his chest and his belly swelling slightly outwards. I didn’t know what an erection was, just that Phyllis knelt, wearing just a white bra, to cure it in the way that you sucked poison from a wasp sting. I should have been disturbed, but everything about the scene – the way they were framed by the slat of light, his stillness with his hands holding her hair and his face turned away – made it seem like a ceremony from some distant world that I would always be forced to witness from outside.

But I was outside everything now. The whole of Navan – and even the Nobber bogmen arriving in bangers with shiny suits crusted in dandruff – knew it. Pete Clancy perpetually devised new means of public ridicule. His fawning cronies brought in soiled straw to fling at me and shout that I had left my bedding behind. They held their noses when I passed, making chucking noises and perching like roosting hens on the bench in the concrete shelter.

The funny thing was that – although Navan would never accept a blow-in like Phyllis – Cormac had blended in, accepted and even slyly admired for his oddity. From the day that he contradicted Pete Clancy any bullying of him had switched to me instead, although I noticed that in the yard Slick rarely took his eyes off Cormac. He even made a few friends, boys who similarly seemed to inhabit their own imaginations out on the fringe of things. But for every friend Cormac made a dozen of mine melted away, aware that even association with me could put them at risk of being bullied too.

The town whispered about what was happening to me at home, with neighbours always on the verge of doing something. Teachers after I fell asleep in class, my mother’s only brother who arrived home from England and threatened to call to the barracks. A policeman spent twenty minutes in the front-room waiting to speak to my father, with not even Phyllis daring to send him packing. On another night a young priest came, very new to the parish, after spotting me at school. There was a brief and strained conversation before he left and never came back. Old Joey Kerwin probably called upon the curate with a bottle of whiskey and the advice that he would earn more respect in Navan for not stirring up unnecessary trouble and maybe leaving his guitar in the presbytery instead of flashing it around the altar.

Had my father been unemployed or a mere labourer I would have been taken away to be placed in the chronic brutality which passed for childcare. I would have shared a dormitory with forty other starving boys; been hired out as slave labour to local farmers; taught some rudimentary trade and lain awake, if lucky, listening as naked boys were flogged on the stone stairs while two Christian Brothers stood on their outstretched hands to prevent them moving. After the state subsidy for my upkeep dried up on my sixteenth birthday, the Brothers would have shown me the door, ordering me to fend for myself and keep my mouth shut.

When boys disappeared into those schools they never reappeared as the same people. Something died inside them, caused by more than just beatings and starvation. But that system was designed to keep the lower orders in check and provide the Christian Brothers with an income. For the son of a senior County Council official to be sent to an industrial school was as unthinkable as for a priest to bugger a Loreto convent girl. The middle classes managed our own affairs, with minor convictions squashed by quiet words in politicians’ ears and noses kept out of other people’s business. No action was ever taken about my confinement, my occasional bruises or burst lip, or the fact that neighbours must have sometimes heard me crying. My father just got busier at work and – corralled in the home – Phyllis grew ever more paranoid about ‘the interfering bitches of the town’.

‘What were you saying to that Josie woman from the terrace?’ she would demand if I was a minute late home from school. ‘Don’t think I didn’t see you gabbing to her when I picked up Cormac in the car. Does she think we’re so poor she needs to give you food from her scabby cottage that should have been bulldozed long ago? You get home here on time tomorrow.’

Shortly before my eleventh birthday Mr Casey had begun to interfere. Trenchantly at first, after a long period of simmering observation, and then in subtle ways which made us both conspirators. His garden was an ordered world of potato beds, gooseberry bushes and cabbage plants. A compost heap stood in the far corner, away from the lean-to where he made furniture most evenings. Close to the wall of my father’s outhouse he’d erected a small circle of cement blocks, used to burn withered stalks and half his household rubbish. Before Phyllis’s arrival I remember accompanying my father and Mr Casey on occasional outings to his brother’s farm near Trim on a Saturday morning, returning with a trailer full of logs. Long into the evening his electric saw would be at work, with sparks dancing like fireflies, logs thrown over the hedge into our garden and the softest pile of sawdust for me to play with.

Their joint ventures stopped however after Phyllis perceived some real or imagined slight in Mrs Casey’s tone towards her. Afterwards both men kept each other at bay behind a facade of hearty greetings shouted over the hedge. But they hadn’t properly spoken for two years before the winter evening when Mr Casey heard me crying through the outhouse wall. I recall the sudden thump of his hand against the corrugated iron and my shock, after being so self-absorbed in my shell, that an outsider could overhear me.

‘Is that you, Brendan? Surely to God he hasn’t still got you out there on a bitter night like this?’

His voice made me hold my breath, afraid to reply. I knew I had let my father down and done wrong by allowing Mr Casey to hear me, I wanted him to go away but he kept asking if I was all right. Was I thirsty, scared, had they given me anything to eat? ‘I know you’re in there,’ he shouted. ‘Will you for God’s sake say something, child.’

Possibly my inability to reply finally made him snap. But there was nothing I could say that wouldn’t make matters worse. I huddled against the corrugated iron, hearing the dying crackle of his bonfire and longing for him to go indoors so that I could creep out and sit near it for a time until the embers died. Injun Brendan who roamed the gardens at night, forever on the trail with no time for tepees or squaws.

When Mr Casey’s voice eventually died away I stopped shaking. Too scared to leave the outhouse, I closed my eyes, imagining that my fist – pressed for comfort between my tightly clenched legs – was the feel of a horse beneath me. I rocked back and forth, forcing the warmth of the fantasy to claim me. Injun Brendan, always moving along to stay free. The bruises on my legs were no longer caused by Pete Clancy’s gang lashing out at me as I raced past to get home from school in time. Instead they were rope burns after escaping from cattle rustlers. I fled bareback along trails known only to myself, seeking out the recently constructed makeshift wigwam of corrugated iron sheets which Clancy’s gang met in by the river so that I could tear it to the ground. I had seen it one night among bushes by the Boyne but even in the dark I hadn’t dared approach it. Now the fantasy of destroying it filled the ache in my stomach, blocking reality out until the sound of raised adult voices intruded.

‘Don’t you tell me how I can or cannot punish my own son!’

‘Punish him for what? He’s been two years down in that blasted shed. If his poor mother was alive…’

The voices were so loud I thought they were in the garden. But when I checked through the chicken wire I could see Mr Casey in the dining-room window, with my father looking like he was only moments away from coming to blows with him.

‘It’s no concern of yours, Seamus.’

‘It’s a scandal to the whole bloody town.’

‘There’s never been cause of scandal in this house.’ Phyllis’s voice entered the fray, suddenly enraged. ‘Just work for idle tongues in this God-forsaken town.’

The more they argued, the more frightened of retribution I became. I looked up to see that their voices had woken Cormac. He entered the back bedroom and sleepily looked out of the window. By this time I didn’t begrudge him owning my old bedroom. He looked perfect in that light, gazing down towards the shed, with his patterned pyjamas and combed hair. I was sure he couldn’t see me in the dark but he began to wave and kept waving. We never really spoke now. Phyllis discouraged contact at home and at school we had nothing left to say to each other. The adult voices threw accusations at each other. Cormac stayed at the window until I forced my hand through a gap in the chicken wire, scraping my flesh as I managed to wave back to him. Then he smiled and was gone. When the voices stopped I lay awake for hours, with the memory of Cormac’s body framed in the window keeping me warm as I waited for vengeful footsteps that never came.

It was half-nine before Ebun stirred. Niyi had made coffee and quietly left a mug on the floor beside me, before relaxing his vigilance long enough to disappear down the corridor to the bathroom. That was when I became aware of Ebun languidly watching me slip into my jeans. I hurriedly did up the zip.

‘You slept well,’ I remarked.

Ebun curled her body back up into a ball, lifting her head slightly off the pillow. ‘Where do you go now, Irishman?’

‘I have business in Dublin.’

‘Have you?’ It was hard to tell how serious her expression was, but I found myself loving the way her eyes watched me. ‘I think you are a criminal, a crook.’

‘Crooks generally find better accommodation than this.’

‘Do they? Are you married?’

‘Are you?’

She turned her head as Niyi returned. ‘I think he is a gangster, like the men who smuggled us onto their truck in Spain. He has their look. I think we are lucky not to be killed in our beds.’

The man admonished her in their own language, glancing uneasily across, but Ebun simply laughed and turned back to me. ‘I don’t really think you are much of a crook, Irishman. I should know, after the people we have had to deal with.’

‘This is stupid talk,’ Niyi butted in.

‘I enjoy a joke,’ I told him.

Ebun stopped smiling and regarded me caustically. ‘I wish to dress. It is time you left.’

I stood up to pull on my shirt, thrown by her curt tone. When I arrived in Ireland yesterday I had been nobody, a ghost, ready to do what had to be done and disappear again without trace. The last thing I needed was attachments, but I found myself lingering in the doorway, not wanting to leave just yet. ‘Thanks for taking me in.’

‘Forgive us for not being used to your customs,’ she replied. ‘We didn’t make you queue.’

Niyi muttered something sharply, caught between embarrassment and relief that I was going.

‘She means no harm,’ he said in English. ‘But in Nigeria I did not live this way. I had a good job in my village, yet here I must queue with gypsies.’

‘They have the same rights as us Yorubas,’ Ebun contradicted him from the bed. ‘None.’

Niyi accompanied me out onto the landing and had already started down the stairs when I glanced back. Ebun’s expression was different in his absence as she quietly called out, ‘E sheé. Thank you for last night. Call again, Irishman.’

Her words caught me off guard. I was unable to disguise my look of pleasure from Niyi who escorted me down to the front door.

‘Thank you again. Ò dábò.’ He shook my hand formally, as if entreating me to ignore Ebun’s invitation and regard our encounter as finished. He watched from the doorway until I reached the corner into Dorset Street.

There were more cars heading into town at this early hour than I remembered. Walton’s music shop still stood on North Frederick Street, but the shabby cafe on the corner was gone, with workmen even on a Sunday morning swarming over steel girders to erect new apartments there. The bustle of O’Connell Street felt disturbing for 10 a.m. Tourists moved about even in late autumn and there was a striking preponderance of black faces compared to ten years ago, although one could still spot the standard fleet of Sunday fathers queuing at bus stops. I would probably be among them if I had stayed, although, approaching seventeen, Conor would be too old for weekly treats now, more concerned about having his weekends to himself.

Those separated fathers on route to exercise their visiting rights were a standard feature of the streetscape in every city I had lived in over the past decade. Too neatly dressed for a casual Sunday morning as they felt themselves to be on weekly inspection. Their limbo in Ireland would have been especially grim, with divorce only just now coming into law. Existing in bedsits on the edge of town with most of their wages still paying the mortgage of the family home, arriving there each weekend at the appointed hour to walk a tightrope between being accused of spoiling the children or neglecting them. Living out fraught hours in the bright desolation of McDonald’s or pacing the zoo while the clock ticked away their allotted time.

I knew that I could never have coped with such rationed-out fatherhood. It was all or nothing for me and the only gifts that my gambling could have brought Conor were disgrace, eviction and penury. My feelings for the boy had grown more intense as my love affair with Miriam died. Died isn’t the right word. Our marriage suffocated instead inside successive rings of guilt and failure, disappointments and petty recrimination. The pale sprig of first love remained buried at the gnarled core of that tree, but it was only after the axe struck it that I glimpsed the delicate lush bud again when it was too late. One final gamble, a lunatic moment of temptation had cast me adrift from them like a sepal.

Ten years ago when I flew out to visit Cormac in Scotland there was graffiti scrawled in the toilet in Dublin airport: Would the last person emigrating please turn out all the lights. Half the passengers on that flight were emigrants, fleeing from a clapped-out economy. I had been on protective notice for two months already at that stage, knowing that soon I would receive the minimum statutory redundancy from the Japanese company I worked for in Tallaght who insisted on blaring their bizarre company anthem every morning. Together our workers lighten up the world…

The world needed serious lightening up back then, with life conspiring to make us bitter before our time. Mortgage rates spiralled out of control and the Government cutbacks were so severe that Miriam’s mother died in lingering agony on a trolley in a hospital corridor with barely enough nurses, never mind the miracle of a bed. Miriam didn’t know that it was only a matter of time before we would be forced to sell our house or see it repossessed because of my gambling. There were many things Miriam didn’t know back then, so much she should not have trusted me to do.

At seven Conor knew more than her, or at least saw more of my other world. The places where us men went, places men didn’t mention to Mammy, even if she dealt with them in her work. Our male secret. Bribed with crisps to sit still while I screamed inwardly as my hopes faded yet again in the four-forty race at Doncaster, Warwick or Kempton. ‘What’s wrong, Daddy? Why is your face like that?’ ‘Eat your crisps, son, there’s nothing wrong.’ Nothing’s wrong except that half of my wages had just followed the other half down a black hole. Nothing’s wrong except that I kept chasing a mirage where more banknotes than I could ever count were pushed through a grille at me, where Conor had every toy he ever wanted, Miriam would smile again and the shabby punters in the pox-ridden betting shop would finally look at me with the respect that I craved from them.

No seven-year-old should have to carry secrets, be made to wait outside doorways when a bookie enforced the no-children rule, see his Daddy bang his fists against the window of a television shop while his horse lost on eleven different screens inside. I lacked the vocabulary to be a good father, gave too little or too much of myself. I simply wanted to make people happy and be respected. I hoarded gadgets, any possession that might confer status. I loved Miriam because she could simply be herself and I wanted Conor to be every single thing that I could never be.

Possibly Miriam and I could have turned our marriage around if I had been honest to her about my addiction. Perhaps we would now radiate the same self-satisfied affluence as that Dublin family yesterday on the stairwell of Lisa Hanlon’s house. I might even have been around to disturb the intruders at my father’s house, with him still alive and all of us reconciled. Father, son and grandson. The pair of us taking Conor fishing on the Boyne, watching him walk ahead with the rods while my father put a hand on my shoulder. ‘You know I’m sorry for everything I did, son.’ ‘That’s in the past, Dad, let’s enjoy our time now.’

How often in dreams had I heard those words spoken, savouring the relief on his lined face, our silence as we walked companionably on? The sense of healing was invariably replaced by anger when I woke. The only skills my father taught me were how to keep secrets and abandon a son. There was never a moment of apology or acknowledgement of having done wrong. Nothing to release that burden of anger as I paced the streets of those foreign towns where I found work as a barman or a teacher of English, an object of mistrust like all solitary men.

In the early years I sometimes convinced myself that a passing child was Conor, even though I knew he was older by then. The pain of separation and guilt never eased, drinking beer beside the river in Antwerp or climbing the steep hill at Bom Jesus in Braga to stare down over that Portuguese town. It was always on Sundays that my resolve broke and several times I had phoned our old number in Ireland, hoping that just for once Conor, and not his mother, would puzzle at the silence on the line. But on the fifth such call a recorded message informed me that the number was no longer in service. I had panicked upon hearing the message, smashing the receiver against the callbox wall and feeling that the final, slender umbilical cord was snapped. I didn’t sleep for days, unsure if Miriam and Conor had moved house with my insurance payout or if there had been an accident. Miriam could have been dead or remarried or they might have moved abroad. Yet deep down I knew she had simply grown tired of mysterious six-monthly calls. She was not a woman for secrets or intrigues, which was why she should never have married me.

I crossed the Liffey by a new bridge now and found myself wandering through Temple Bar, a mishmash of designer buildings that looked like King Kong had wrenched them up from different cities and randomly plonked them down among the maze of narrow streets there. I bought an Irish Sunday paper and sat among the tourists on the steps of a desolate new square. The inside pages were filled with rumours of the Government being about to topple because of revelations at the planning and payments to politicians tribunals, along with reports of split communities and resistance committees being formed in isolated villages that found themselves earmarked to cater for refugees.

I stared at the small farmers and shopkeepers in one photograph, picketing the sole hotel in their village which had been block-booked by the Government who planned to squeeze thirty-nine asylum-seekers from Somalia, Latvia, Poland and Slovakia into its eleven bedrooms. Racists, the headline by some Dublin journalist screamed, but their faces might have belonged to my old neighbours in Navan, bewildered and scared by the speed at which the outside world had finally caught up with them. The village had a population of two hundred and forty, with no playground or amenities and a bus into the nearest town just once a day. A report of the public meeting was stormy, with many welcoming voices being shouted down by fearful ones. ‘You’ll kill this village,’ one protester had shouted. ‘What do we have except tourism and without a hotel what American tour coach will ever stop here again?’

This confused reaction was exemplified in the picture of a second picket further down the page. This showed local people in Tramore protesting against attempts to deport a refugee and her children who had actually spent the past year in their midst.

There were no naked quotes from the South Dublin Middle Classes. A discreet paragraph outlined their method of dealing with the situation. There were no pickets here, just a High Court injunction by residents against a refugee reception centre being located in their area, with their spokesman dismissing any notion that racism was involved in what he claimed was purely a planning-permission matter.

Two Eastern European women in head-dresses sat on the step beside me, dividing out a meagre meal between their children. I closed the paper and, leaving it behind me, located a cyber cafe down a cobbled sidestreet which was empty at that hour.

My new Hotmail account had no messages, but there again whenever I left a city I was careful to leave no trace behind. I got Pete Clancy’s e-mail address from the leaflet in my pocket, sipped my coffee and began to type:

Dear Mr Clancy,

‘Help me to help you’, you say. Maybe we can help each other. Your problem in the next election could be how to know you have reached the quota if you’re not sure that you have all the magic numbers. Your father once joked that death should not get in the way of people voting. It need not get in the way of the recently deceased talking either.

Fond memories,

Shyroyal@hotmail.com

I stared at the message for twenty minutes before clicking ‘send’. It was a hook but also a gamble, pretending to know more than I did. What would Clancy make of it – a local crank, a probing journalist shooting in the dark, a canvasser for another party trying to snare him? Some party hack might check on the messages for him, scratch his head and just delete it. But I figured that the odds were two-to-one on Clancy himself reading it and five-to-two that the word ‘Shyroyal’ might capture his attention.

I had only heard it once in childhood, when Barney Clancy turned up in a gleaming suit, slapped his braces and joked to my father: ‘This is my Shyroyal outfit. Sure isn’t Meath the Royal County and don’t I look shy and retiring?’ Something about his laugh made me glance at him as I came up the path, after running a message for Phyllis, and something in my father’s eyes made me look away, knowing it had a buried meaning not meant for the likes of me.

By the age of twelve I had learnt to pick the lock on the filing cabinet, opening the drawers gingerly at night, uncertain of what I hoped to find there. Secrets that would make me feel special, photos of my mother or some other token to break the loneliness. The letterheads were torn off the sheaf of paper in the top drawer but, even at that age, I recognized them as bank statements for something called Shyroyal Holdings Ltd, with an address on an island I had never heard of. The rows of figures meant nothing to me, but I could read the scrap of writing on the cigarette packet stapled to them: Keep safe until I ask for them. It was unsigned, but I would have recognized Barney Clancy’s handwriting anywhere.

Not that I had considered the statements as suspicious back then. Funds were constantly being raised for the party on the chicken-and-chips circuit or by good men like Jimmy Mahon at church-gate collections. This seemed just another component of the adult world where important people were making things happen for the town. If I hadn’t previously overheard Barney Clancy’s joke to my father the Shyroyal name would not even have registered. Indeed, at the time I just felt disappointment that nothing belonging to my mother was actually concealed in the drawers.

Even today I couldn’t be certain if my suspicions were correct or the product of a need for revenge. I could barely even recognize the country outside the cyber cafe window and felt doubly a foreigner for half-knowing everything. I found myself thinking of Ebun again, how she had looked calling out from her bed this morning and how Niyi too had looked, staring back at us both.

The cafe was starting to fill up. I finished my coffee, collected my bags from the bus station, found a hardware shop open on a Sunday where I could purchase a crowbar and booked myself into an anonymous new hotel on the edge of Temple Bar. It was important that I shaved at least once a day to ensure that black stubble didn’t clash with my hair. Lying on the bed afterwards, I repeated the name Brendan out loud, as if trying to step back inside it. I remembered how Miriam and Cormac used to say it, the way Phyllis had twisted the vowels, and tried to imagine Ebun pronouncing it. But each time it sounded like a phrase from a dead tongue last spoken on some island where the only sound left was rain beating on bare rafters and collapsed gable ends.

During the first fortnight after the train crash a sensation of invisibility swamped me. All bets were suddenly off, because not even bookies could collect debts from a dead man. Our endowment policy ensured that once my death was confirmed, the house belonged to Miriam with the outstanding balance of the mortgage written off. A company scheme in work meant that, because I died while still employed by them, my Japanese masters would have to grudgingly cough up a small fortune. That was before taking my own life assurance policy into account, not to mention the discussion in the newspapers that I carefully read every day about a compensation fund for victims. My name was there among the list of the missing. There was even security footage of me splashing out on a first-class ticket at the booth ten minutes before the train left Perth. Death had finally given Brendan Brogan some cherished status. He was virtually a celebrity, but he wasn’t me any more.

I was free of all responsibilities, shunting quietly across borders on another man’s passport. Not that my initial decision was clear-cut. In the hours after the crash I wasn’t sure what I had wanted, except perhaps to make Miriam suffer a foretaste of what it might be like to lose me. Little enough beyond recriminations still held us together. But I knew that her anxiety would be intense as she listened to reports of the crash and prayed for the phone to ring, aware I was supposed to be on the train.

Rarely had I experienced such a sense of power. For months I had helplessly waited on word of the factory closing. At night I had kept dreaming of horses that I knew had no chance of winning, but next day I would back them in suicidal doubles and trebles, waiting for that one magic bet to come up that might buy me space to breathe. By night I woke in a sweat, thinking that I’d heard the doorbell ring with a debt-collector outside. By day I hovered inside the doorway of betting shops in case some neighbour passed who might mention seeing me to Miriam. On buses I found myself incessantly saying to Conor, ‘I bet you the next car is black,’ ‘I bet you we make the lights before they turn red,’ ‘I bet you…I bet you…I bet you…’

Brendan Brogan was a man who couldn’t stop betting. But wandering through Perth on the morning of the crash I had the bizarre sense of having stepped outside myself. I wasn’t that pathetic gambler any more. Suddenly I was the man in control who could choose when to release Miriam from her anxiety by phoning home. I imagined the relief in her voice and, with it, an echo of her earlier love. Yet once I made that call my new-found power would be gone. I would have to explain my getting off the train before it started, how I had chickened out of meeting Phyllis in Glasgow. I would return to Ireland to face the hire-purchase men and money-lenders, the pawnbroker who held all of Miriam’s mother’s jewellery which she believed I had put in the bank for safe keeping, and my seven-year-old son baffled by the civil war fought out in the silences around him.

I knew that my not phoning her was cruel and petty, but it was also a confused attempt to reach Miriam by letting her understand powerlessness. It was not that I hadn’t wanted to tell her about my childhood, but I had never found the words that wouldn’t make me feel dirty by discussing it. Her mind was too practical to understand why people had done nothing. But the hang-ups were totally on my part. I could never cope with her lack of guile and she had felt hurt by how I clammed up on nights when the memories turned my knuckles white.

Before Conor was born I genuinely believed I had outgrown that hurt. But the older he got the more I found myself forced to relive my childhood, imagining if Conor ever had to endure the same. Surely at some stage my father must have felt this same love for me as I felt for Conor, an overwhelming desire to protect him at any cost, to kill for him if necessary. Yet every time Conor laughed I remembered nights when I cried, with every meal he refused to eat I recalled ravenous hunger. Carrying a glass of milk up the stairs for him in bed I remembered creeping from the outhouse to cup my hands under the waste pipe from the kitchen sink. What father simply abandons his first child? On some nights Miriam would find me cradling Conor in bed, his sleeping cheeks smudged by my unexplained tears. I would want to go to Cremore where my father now lived and punch his face, screaming, ‘Why, you bastard, why?’

I did actually mean to phone Miriam from Perth after I had scored my point. But somewhere along the line I left it too late. By 9.15 the phones would already be buzzing, with Phyllis calling my father from Glasgow airport and him contacting Miriam. By half-ten I knew her anxiety would be tinged with anger. If I phoned now she would know that I had deliberately been playing games.

And it was a game until then. Partly I was in shock from the realization of how close I had come to still being onboard the train when it left Perth. But my mind was also in turmoil from trying to comprehend the events that had occurred since my arrival in Scotland two days before.

Eleven a.m. had found me outside a TV shop in Perth, watching live pictures of firemen frantically working. Reports were booming from the radio in the pound shop next door, with talk of signal failure and dazed survivors found wandering half a mile from the track. I had more cash on me than I had ever handled before, money nobody else knew about. Enough for a man to live on for a year, but not enough to do more than temporarily bandage over the cracks at home, even if I didn’t blow it in the first betting shop in Dublin. I had needed time alone to mourn and come to terms with Cormac’s last words to me that called for some new start, some resolution. I had also needed time to deal with Cormac’s revelations about my father. The facts should have been self-evident had I wished to see them, but in my ambiguity of both hating him and craving his respect, I had always shied away from over-scrutinizing my father’s relationship with Barney Clancy.

I had bought shaving foam in a mini-market, sharp scissors and a disposable razor. Nobody came into the gents’ toilets in the small hotel beside the bus station while I was removing my beard there. I cleaned the sink afterwards until it shone, putting the scraggly hair and foam and used razor in a plastic bag. The air felt freezing against my cheeks as I dumped them in a waste bin.

People stood around the station in numbed silence as I caught a coach at half-eleven, barely aware of my destination until I saw ‘Aberdeen’ printed on the ticket. Cormac’s voice seemed to be in my ear, giving me strength. Go for it, brother, take them all for the big one. Twenty-four hours before I had cradled his body in his flat, trying to hold him up even though I knew from the way he hung on the rope that his neck was broken. But suddenly it felt like we were together in this, thick as thieves, the inseparable duo that strangers thought we were when we first moved into a flat together in Dublin. I had felt as if I was outside my body when the bus pulled away from the station. I was Agatha Christie faking amnesia to scare her husband. I fingered the first-class train ticket that was still in my pocket. After all the useless bookies’ slips cradled in my palm there, this was the magic card which I had acquired without even knowing. With it I could fill a royal flush, turn over the card that made twenty-one, see the most impossible treble come up. Cormac’s ghost and I were hatching the biggest scam in the history of Navan, laying down the ultimate bet and the ultimate revenge on my father too. This buzz was more electric than seeing any horse win. I didn’t crave respect from the other passengers, it was already there because I was someone else now, free in a way that I thought only people like Cormac could ever know.

When we had reached Aberdeen my nerve almost failed. I spent twenty minutes in a phone box, constantly dialling Miriam’s number, then stopping at the last digit, biting my knuckles and starting all over again. Cormac’s ghost didn’t seem inside me any more. I was my old insecure self, about to muddle my way through some excuse, when I glimpsed a hoarding advertising a ferry about to leave to the Orkney Islands from Victoria Quay. Go for it, go for it. Cormac’s tone of voice was the same as when he had dared me to do things in the outhouse.

An hour into the voyage it started to rain and the wind was bitter, but I stayed up on deck on the ferry, all the way past the Moray Firth and beyond John O’Groats. Eventually in the darkness Stromness port came into view on the island called Mainland. From there I had taken a taxi to a hotel in Kirkwall, where I sat alone in the bar to watch an extended late-night news bulletin about charred bodies still being located among the train wreckage and the death count rising.

Even then it wasn’t too late to change my mind. Miriam would be frantic, with Conor crying as he sensed her anxiety. But life without me was going to occur for them soon enough anyway. The Japanese factory would be the fifth major closure in Dublin since the start of that summer. Every day I had endured the torture of other workers looking for the return of borrowed money. Even if I used the cash in my pocket to clear every debt, how long would it take me to return to the equilibrium of being in the gutter again? It was the one place I felt safe in, where I had nothing more to lose. Winning always unhinged me. Even amidst the euphoria at seeing my horse cross the line I had always been panicked by the money being counted into my hands, knowing that life was toying with me, tauntingly postponing the inevitability of being broke again.

Fragments of my last conversation with Cormac had entered my head:

Maybe you just think you’d blow it becaus you’ve never felt the power of fifteen thousand pounds cash in your hands…Make something of yourself. Ask yourself who you want to be. Suddenly I didn’t have to be a loser whose son would learn to cross the street with his mates to avoid me. I could become someone else in his eyes, revered like my mother in a society where goodness was instantly conferred by early death.

I realize now that I wasn’t thinking straight back then, still in shock from Cormac’s suicide. But as I sat in that hotel bar and listened to the experts being interviewed, it seemed that my getting off the train had been a miracle of Cormac’s doing. There had been no cameras that I was aware of on the platform or at the station’s side entrance. I could never explain to Miriam where the fifteen thousand pounds had come from, nestling in the envelope between the two passports in my jacket pocket. She would think I had been gambling again and I was. I was taking the biggest gamble of my life to provide every penny they would need for years to come.

Another pundit was talking on television as I left the hotel bar long after midnight. He repeated the only fact that the experts seemed able to agree on. The heat inside the first-class carriages had been so intense that investigators would never establish just how many bodies were reduced to ash inside them.

The old sandstone buildings beside the quay at Kirkwall had an almost Dutch feel in the dark as I walked along the pier. An elderly man and his dog reached the end and turned to walk slowly back. Normally I didn’t smoke but I had purchased a packet of the tipped cigars which Cormac liked. I would need to buy red dye for my hair tomorrow and glasses like Cormac wore in his photo, but already with the beard gone a vague resemblance was there. I was an inch taller, but did officials really check such details? I hadn’t known where this voyage would take me, but surely far enough away from my old life that if I had to end it nobody could trace me back.

The paper inside my own passport was thick. At first the cigar merely singed it, making the edge of the pages curl up. Then suddenly a flame took hold. I glanced behind. The old man was out of sight, the tied-up fishing boats were deserted. Gulls scavenged under the harbour lights for whatever entrails of mackerel and cod had not been washed away. The flames licked around my photograph, consuming my hair, then my forehead, eyes and mouth. The cover was getting too hot to hold, my date of birth burnt away, my height, colour of eyes. I had flung my old self out into the North Sea and saw the passport’s charred remains bob on the waves before slowly sinking from sight.

At half-two I got dressed again, ripped the lining inside my jacket so that the crowbar fitted into it without attracting attention, and left the hotel to stroll up towards Phibsborough. That familiar Sunday-afternoon malaise lingered around the backstreets here, but new apartments crammed into every gap along Phibsborough Road itself, standing out like gold fillings in a row of bad teeth.

The tiny grocer’s opposite my old flat had been replaced by a discreet one-stop-shop for transvestites. A single-storey country dairy still stood beside it, from which an old man used to emerge each morning on a horse-and-cart. But it looked long closed down, a quaint anomaly which – by fluke or quirk of messy will – the developers had overlooked in their frenzy.

A new stand had been built in Dalymount Park, but little else appeared to have changed to suggest that the ground wouldn’t pass for a provincial Albanian stadium. Bohemians were playing Cork City at home. I paid in at the Connacht Street entrance and, once inside, paused to lean against the wall of the ugly concrete passageway beneath the terraces which was empty except for a late straggle of die-hard fans.

Nostalgia brought you to the funniest places. The game had already started but I had no interest in climbing up to the terraces. I wanted to forget the bitter finale of my love affair with Miriam and recall the magic of its origins. Everything about the Ireland I had left seemed summed up in the haphazard disorganization of that February night of mayhem and terror in 1983, when Italy arrived as reigning World Champions to play a friendly international. Rossi was playing that night as well as Conti and Altobelli who scored their second goal. Yet nobody in authority bothered to print tickets for the match. The crowd simply drank in the pubs around Phibsborough until shortly before kick-off, then spilled out, fumbling for change as we formed the sort of scrum which passed for an Irish queue.

As a nation we knew we were down and out – with Barney Clancy, by then a senior cabinet minister, hectoring us about living beyond our means. The World Bank hovered in the wings, itching to take over the running of the country. But there seemed a sense of anarchic freedom about those years as well. Half an hour before kick-off I was still drinking in the Hut pub with Cormac and his friends; some of them urging us to finish up while others clamoured for a final round.

The crowd was already huge as we approached the stadium, clogging up the alleyway which led to the ground. Yet it might have been okay had an ambulance not passed down Connacht Street with its siren blaring. We squeezed even further up the alleyway to let it pass, but more latecomers surged into the cleared space in its wake, causing a swollen crush. People responded with good-humoured jokes at first, shouts of ‘Shift your hand’ and ‘Mind that chiseller!’ But soon it became difficult to breathe.

The tall girl with permed hair was the first person I saw who panicked. But she was not even going to the game; I’d seen her emerge from a nearby house and she was unable to prevent herself getting caught in the crowd. A roar erupted inside the ground as the whistle blew for kick-off. I had ten pounds on Italy to win two–nil, with Rossi to score the opener. The crowd pushed harder, anxious to miss nothing. One minute Cormac was by my side, the next we were separated in the turmoil. But my only interest was in rescuing that brown-haired girl. I couldn’t explain the attraction, I just knew I had to reach her.

She turned around, trying to plead with people to let her out. But another surge pushed everyone forward, knocking her off-balance. Her hands flailed out helplessly. She was ten feet away and suddenly I hadn’t cared who I hurt in attempting to reach her. Not that etiquette mattered any more. Her panic infected the crowd who realized they were likely to be crushed against the walls long before reaching the turnstiles. There was no way out. Fathers held their children tight, using elbows and fists to try and generate more space.

We were twenty feet from the stadium, nearing the zenith of the crush, when I lost sight of her. Her mouth opened as if to scream, her head went down and never reappeared. I took a blow to my skull as I clawed my way through. Then I was lifted up, my feet no longer touching the ground. People trapped against the wall screamed in terror. I saw her blue coat through a mass of legs. She seemed to be lying on something. My feet trod on somebody, then briefly touched the ground before I was pushed forward, landing on top of her. Her head turned. She looked at me, wild-eyed, terror-stricken.

‘It’s okay,’ I wheezed, ‘I’ve come to help.’

I don’t know if she heard or understood. I was just another man crushing her. I couldn’t save her or myself or anyone. When I tried to shield her head she pushed me off like an attacker. I wanted to explain, but the breath was knocked from my body.

Then my legs found space in the current of people. I felt myself being lifted off her. The police had managed to open the exit gates and bodies were suddenly sluiced into the ground. I put my arms around her, half-lifting and half-dragging her. She had been lying on a collapsed crowd barrier, in which her shoe was entangled. The wire cut into her trapped foot. I pushed against the crowd, making enough space to free her foot, then tried to help her up but she seemed unable to walk. We were carried inside the ground by the crowd’s momentum, before people broke away, rushing in different directions. I found a wall and helped her hunch down against it, trying to offer comfort with my arm around her as she cried. She looked up suddenly, pushing me off.

‘Just leave me alone! Leave me!’

She almost spat out the words. I had backed away, finding that my own legs could barely support me. I sat against the opposite wall, watching her cry. The passageway was quiet except for more latecomers wandering in, delighted they didn’t have to pay. Parents were leaving, holding sobbing children. Policemen argued with officials. I walked out into the alleyway, wondering how many would have died if the gates hadn’t been opened in time. Few clues were left to suggest that panic, except for some lost scarves and, here and there, the odd shoe. I found hers beside the barrier, with its heel broken, carried it back inside and waited until she looked up before offering it to her. She wiped her eyes with a sleeve and tried to smile.

‘Stupid bloody match. Who’s playing anyway?’

‘Italy. The World Champions. Your heel is broken.’

‘Only for you my neck would be too. Thanks.’

‘That’s all right.’

And everything was, too that night, like magic. Rossi scored first with Italy winning two-nil, a fourteen-to-one double off a ten-pound bet. We laughed all the way down Phibsborough Road to the Broadstone. At twenty Miriam Darcy was two years younger than me, just finishing her training as a social worker and ready to change the whole world. She leaned on my shoulder, limping slightly and carrying both shoes in her hand. Double-deckers pulled into the bus depot, with its statue of the Virgin high up on the wall. The King’s Inn rose to our left and blocks of Corporation flats to our right. Glass was smashed on the corner where winos had occupied a bench. I gave Miriam a piggyback over it, laughing as she slapped me like a horse when I stalled and threatened to throw her off. We reached Great Western Way, with its boxing club and row of ancient trees, then the Black Church, around which Miriam’s mother was afraid as a child to run three times in case the devil appeared. Every step had seemed magical as I bore her into the old L-shaped street where she lived with her mother.