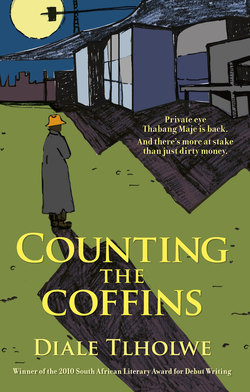

Читать книгу Counting the Coffins - Diale Tlholwe - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 6

ОглавлениеThe last time I had been in this Berea flat was the time I had brought her home drunk. Strangely, maybe through some instinct of self-preservation or ingrained self-respect, that time Tolo had sobered up just as we had parked outside her building. Perhaps the gusty late-summer’s rain had helped. She had walked quite steadily right up past the security man, towards the lifts and into her fifth-floor flat before passing out on the sofa. I had let myself out after making sure that the door would lock itself behind me.

Today she was different, very sober, almost alarmingly animated – manic, some people might have said. Drunk without the benefit or the trouble of drinking, others might have said.

She went straight through to her bedroom, leaving me in the small sitting room. She left the door ajar and carried on talking. I was not really listening, as I was trying to work out how to dissuade her from her reckless intention to get involved in my plans. It was out of the question, my partners would be far from pleased and she might get hurt or put others in danger. There was something not altogether right with her attitude and behaviour. Her reasons were good and her arguments admirable but . . . this had been too sudden.

Was she not acting a little like I had during my last days as a teacher, when I had accidentally got into this type of work? I had been full of vinegar then, disregarding rules and despising regulations.

She was still talking, but not to me. She was arguing fiercely with someone over the phone and was running a bath at the same time, so I only heard broken snatches of a conversation about a party. This was it, I decided. I am not taking her to any party. I waited for her to return with this firm resolve burning in my breast. I was not going to help her get back into the bottle. I was still struggling with it myself and I’d be damned if I’d help anybody else backslide.

She came striding back in a completely different outfit. It was pretty and she looked terrific, but that was nothing to me now. I would put her straight as soon as she stopped talking.

“We are going to some lousy party, but it does not matter how you are dressed. As a man you can get away with anything as long as you occasionally say something amusing or intelligent. Or better still, don’t say anything at all. The old mysterious-male act still works, you know. Or gajwang?”

“I don’t know and I have no interest –”

“You are right, of course, because that strong, silent alpha-male routine can also mean dull, moody and slow.”

Man, she had always been good at taking what you said, turning it inside out and giving it her own spin. The party was becoming definite and I was weakening. I had had no social life and light-hearted fun for some time. Breaking out for once and rejoining the absurd social whirl did not seem like a bad idea. Some good might even come out of it. It was in the course of duty, after all, the interests of justice; the reasons were crowding in at an alarming rate.

I put on a last half-hearted show of resistance.

“We are not going to a party,” I said in my best schoolmaster tone.

She took no notice of me and continued transferring odds and ends from her large, battered day bag to a smaller, prettier party bag.

“I was talking to someone just now, you see. He is connected. He is always going to these things and he meets all sorts of interesting people. He mentioned something about a party this weekend where some of the same people who were involved in that mall thing would be present. It’s tonight. So let’s go and take a look at them. I know the place.”

“Hey, hey, hey, Tolo. Slow down, now. Nkosi might be there and he knows me.”

“He won’t be there. These are the people who lost out, so they are not his fans.”

“Why are you doing this?”

“I told you on the way here. I’m tired of sitting on the fence with my genteel private-school education, interviewing genteel people who have never seen ninety-nine per cent of their own city or country.”

She sat down on the sofa and looked at me stalking around the room. I was going over the plan I had tried to hammer out back at the office with Thekiso and Ditoro. It still had too many rough edges and would not kick in till next week, so I had two days of virtual inactivity. Why not take advantage of Tolo’s suggestion and get started? It was only a party and I was merely going to observe, be part of the background furniture. But it could wreck everything if these people remembered me when I approached them in another guise. Was this not sabotaging my own operation?

“The place will be overflowing. No one will pay you the slightest attention. They won’t remember your face or name tomorrow. They’ll pass you on the street in broad daylight on Saturday without even a blink,” Tolo said, as if reading my mind. “They meet crowds of people every day, hangers-on and the like. So unless you do something incredibly stupid they will not –”

“Okay, Tolo. Enough! Who is this connected friend of yours?”

“Oh, Jacky. He used to be a journalist too. Now he is a spokesperson for some high official.”

“Which one? The official, I mean.”

“There’s been so many of them. Jacky is always moving around, advocating one cause today and another the next. He is a typical new South African. Right now, I think it’s small-business enterprise. After the mall mess he was in public works. Anyway, the same people are usually involved in all these things in different ways – public, private and everything in between.”

“It’s not my mess,” I said, still pacing the floor.

“Then why are you trying to clean it up when the people who were worst hit are lying low? It’s your mess because it’s personal.”

“So why are you getting excited about it?”

“It’s personal too,” she said in a strange, subdued voice. I stopped and looked at her sharply. Her eyes were on the ceiling, her feet on the low coffee table and her hands draped over the back of the sofa. Completely at ease, yet giving the impression of intense suppressed excitement, the idea of a compressed spring that could explode into activity at any moment.

“Tell me about it,” I invited her.

She took a long time responding. So long I knew she was not going to, had in fact forgotten about me and my intrusive question. I was not going to beg her to share her private demons. I had enough of my own. If she was still engaged in the war of attrition with her editor and her father and wanted to show them she was a good investigative journalist, it was her affair. It might even help me corner Sandile. I had given her unattributable leads in the past and she had fed me unpublishable information in return. We trusted each other to use whatever we learnt with discretion.

“Where is this party? I hope it’s not too far or out of the way,” I said at last, to bring her back from whatever dark place she had gone to.

“Glenvista is not out of anybody’s way,” she said as she roused herself. “It’s right in the middle.”

“It is not,” I objected. “If I have to drive there and bring you back here, then drive myself home, who knows when that will be.”

“Who said anything about you driving me? I have my own car, you know.”

“So we arrive as a couple but in different cars?” I said sceptically.

“Who said we are a couple? But I see your point. It’s your investigation,” she shrugged and stood up, “so you should not complain about a little inconvenience. We’ll take your car.”

We left together at eight. Like I said, she was good. When my daughter starts looking around, I’ll get her to sit on Tolo’s knee and take some lessons on one-upmanship and street diplomacy.