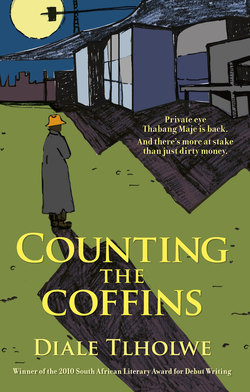

Читать книгу Counting the Coffins - Diale Tlholwe - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 1

ОглавлениеThe depth of the pain of loss, the breadth of its torment, is far greater than all the plagues in the entire expanse of the universe, its permanence too obvious to ignore.

Some insensitive fool once said work is the best way to take your mind off your troubles. A multitude of pathetic fools parroted the one who had first said it until it became an established truth that allowed no contradiction. It always happens with all these old sayings, incubated in the brains of halfwits.

So I was allowed no break in my work – to do so would be an admission of weakness on my part. I could read all this in the eyes of my comforters. It was now almost a month since the dreadful accident had happened and I was expected to have snapped out of it and moved on.

So, on this Tuesday morning, I sat at my desk in my disorderly cubicle (which I call an office when I feel grand) and looked blankly at an orange file. All I could see was the Lesego I had left at the hospital that morning. The inconsolable Lesego had lost our unborn child when her car skidded and rammed into a concrete wall while trying to avoid a drugged, misbegotten teenager in his father’s car. That the boy had overturned the car and killed himself trying to flee the scene did not comfort me. He was now just another body in another coffin in a country of coffins, beyond all recrimination and blame.

It was the parents I had found objectionable.

I had listened to them trying to justify their child’s actions at the scene. They went so far as to almost blame Lesego for the tragedy. Modimo – God! How I nearly went for that stupid man, the father, but Thekiso’s stern eye had been on me as he shook his head in warning. And, of course, the police, the media and the paramedics had been all over the place. It was not the right time or place to be hysterical. Not with Lesego on a stretcher looking at me with pained and questioning eyes. So I had got into the ambulance with her and held her hand, even after she slipped into merciful unconsciousness.

We had not even been properly married yet, according to our more censorious relatives and other like-minded types. We had had just a small private ceremony and lunch and a limp party afterwards with close relatives and a few friends. The Big Bang Wedding was scheduled for after the babies were born. Only the girl twin had survived the crash and was now clinging desperately to flickering life in an incubator in the same hospital in which Lesego was confined.

“Have you started on that file?” Thekiso’s uncompromising voice interrupted my thoughts. He is a firm believer in the “work as a palliative” adage. He is also the chief partner of our firm – Thekiso and Ditoro: Security Consultants and Private Investigators, a highly elastic and useful tag that encompasses everything from providing bodyguards to minor celebrities and politicians with delusions of grandeur, to investigating dubious business people on behalf of suspicious associates. But there are genuinely frightened people out there with real enemies, just as there are indeed virulent human viruses polluting the ethical bloodstream of this city, if not the country.

“I thought you might find it interesting, Thabang,” he went on in a softer tone. A tone I did not like at all. Surely Thekiso was not going to go mawkish and sentimental on me? I could not handle that. I would take a leave of absence if that was the way things were going. I would resign. I would lock my personal desk drawer. I would work from home. I would call a staff meeting and tell them . . . I fumed and did nothing.

Though Tex Thekiso was a fully qualified lawyer, he had never practised. Still, I did not expect this kind of putting-a-fragile-witness-at-ease tone from him. It was vaguely disorienting.

But I was reading all the while as these furious ideas churned and tumbled in my head. A name caught my eye. Here was a name I would never forget: the name of the drugged boy’s father.

I turned around sharply but Thekiso had already left. I nearly overturned my chair as I leapt after him. He was seated behind his desk when I burst into his large, comfortable office.

“What is it now? You want to go home?” he asked with a straight face.

“What is this?” I dumped the orange file on his desk.

He frowned and then, unbelievably, he smiled. Once, maybe twice since I began working with him had I seen that crazy, lopsided smile. It was boyish, disarming in its own wry way, and removed a dozen years from his forty-year-old face. Why he was so stingy with this asset was not the point now.

“This is a file, if I am not mistaken,” he said.

“But where did you get it?”

“You mean the notes? I wrote them. The information I got in the usual way. Someone wanted us to check on something.”

“When was this? It can’t –”

“It is an old file. The client never turned up for a meeting and we put it aside and forgot about it. No client, no money, no investigation.”

“But you remembered.”

“I always remember.”

“Was the investigation going anywhere?”

“It could have. But no client, no –”

“No money, no investigation,” I finished for him. I grinned sourly, but he had retreated into his usual impassible self.

“We are not a government agency or the United Nations peacekeeping force,” he rebuked me. I didn’t mind. We were back on familiar ground – slightly cordial and mildly acerbic.

“Right, then, can you fill me in?”

“You can still read, can’t you?”

“Why did you give it to me?”

“You have motivation and that’s usually half the battle won right there.”

“Even so –” I started to protest that we would be saving time and I’d be better prepared if he just told me. That same motivation might make me see things less clearly – but I was not going to tell him that. He saw it coming, and stopped me before I began. The torrent of my impatience dried up before I had said a word of it.

“Go and read the damn thing first. Thoroughly. Then we’ll discuss it. I will also want Ditoro in on it.”

He was talking about our own resident ex-policeman and intimidation expert, Tau Ditoro. I sometimes wonder how many of Tau’s type are out there. Sometimes it seems to me they are all over the place, toiling diligently on both sides of the legal fence.

I left him staring morosely out of the window before him at his favourite view: a dirty old brick wall. What did he see or read in it? The changing history of our society recorded on its slimy dampness? I used to wonder. I personally preferred the view out of the window behind him. It offered a more congenial and attractive skyline of Johannesburg – the sight of brave new buildings thrusting ever upwards. But destined to be consumed by smoggy skies if they were ever finished. Still, for a moment you could believe in the human spirit . . . an unstoppable force in everlasting upward motion.

These days, I sometimes think I can also catch a glimpse of the future in the dreary and scarred griminess of the wall.