Читать книгу Finding Lucy - Diana Finley - Страница 17

Chapter Eleven

ОглавлениеThe time came when I had to admit to myself that the initial period with Lucy was not easy, not easy at all. Should I have expected such difficulties? Yes, I realised, perhaps I should, but my direct experience of small children and their responses had been extremely limited.

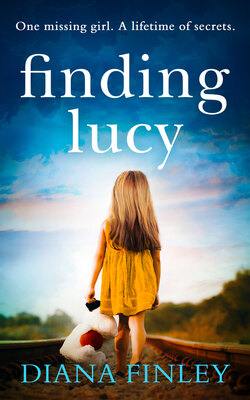

It took my little daughter much longer to settle in her new home than I had anticipated. All my careful preparations – with Lucy’s happiness in mind – seemed to mean nothing to her. The pretty bedroom with its colourful matching curtains, cushions and bedding depicting amusing cartoon-like jungle scenes; the carefully chosen toys and books; the cheerful pictures and friezes decorating the walls: none of these things elicited the slightest interest or pleasure in Lucy.

The first week was the hardest. During the daytime, Lucy mostly lay on the floor, crying and moaning. She would kick and scream when I tried to comfort or even approach her. She woke frequently during the night, and her screams were pitiful. So often did she wake with soaking sheets that in the end I had to put nappies on her during the night.

For some days after her arrival, she would eat and drink nothing but a little water, and I began to fear seriously for her health. At last, in desperation, I added a little sugar to a saucepan of milk, warmed it and filled a baby’s bottle. I lifted her onto my knee. At first she arched her back and howled like a wild creature, but I persisted, holding her firm, and after a while she submitted to being rocked gently on my lap. She sucked rhythmically on the teat, and took the whole bottle, her eyes rolling up into their lids. Her body went limp with exhaustion. At last she fell into a deep sleep.

This was a turning point. I realised that perhaps Lucy had missed out on some crucial early stages of babyhood. Of course she had, with neglectful parents like hers. Why had I not thought of it before? I endeavoured to restore these vital experiences to Lucy, even though she was now about two or two and a half years old – hardly a tiny baby. Yet, what did it matter if, in private, I rocked Lucy to sleep like an infant, hummed and sang to her when she was distressed, allowed her a dummy and fed her with a baby bottle?

Lucy talked little at first, but every now and then she repeated a tedious little litany in a plaintive questioning voice.

‘Mam? Dad? Wy-yan? Polly …? Tacy … Mam?’

By this time I had learned more of Lucy’s former family from television and newspaper reports. I knew that “Tacy” referred to her previous name. What a fortunate chance that Stacy and Lucy sounded not totally dissimilar. Surely she would soon adjust? “Wy-yan” of course was Ryan, the brother nearest to Lucy in age – whom I had witnessed paying her little enough attention, indeed, abandoning her on the pavement outside her former house. He was, in my opinion, quite undeserving of her affection. It took me a while to remember that Polly was the name of the filthy, naked and disfigured doll, with which Lucy had been playing when I first set eyes on her.

* * *

The first time I dared to take Lucy out of the house was many weeks after her arrival. I suggested we should go and buy a “new Polly” for her. Lucy’s little face lit up, and she actually smiled! My heart turned to liquid and I nearly wept aloud.

‘Buy Polly,’ she said, nodding eagerly.

We made our way to the High Street, where I had noticed a small toyshop. The assistant immediately stepped forwards and asked how she could help us.

‘We’re looking for a doll,’ I explained. ‘In fact, my little girl has lost a favourite old doll, and I’m hoping to find a similar one for her.’

We were shown the rows of baby dolls, brown dolls, black dolls and white dolls, boy dolls and girl dolls, dolls with plastic heads and dolls with hair. I found one that seemed to me the closest in size and features to Polly, although this one was in pristine condition, quite unlike the stained and discoloured appearance of the original. The doll had blond hair tied up in a bunch on top of her head with a pink ribbon. She wore a frilly pink dress and knickers.

The box in which she reclined also contained a tiny plastic brush and comb, a baby bottle and a small yellow potty, all held to a cardboard base with rubber bands. The doll’s face wore an expression of exceptional stupidity. When upright, her eyelids fluttered open to reveal large blue, sightless eyes. Her red lips were pursed in a look of perpetual astonishment, heightened by the small round hole in their centre, presumably into which the bottle could be inserted.

‘She wets an’ all,’ the assistant informed Lucy, who regarded the doll balefully.

‘Not Polly,’ she said. I crouched down in front of the pushchair, facing Lucy, and spoke in a quiet whisper.

‘No, Lucy, but she’s like Polly, isn’t she? You’ll see, when we get home we’ll take her clothes off and give her a bath, shall we?’

She frowned. ‘Not Polly.’

I quickly paid and we pushed out of the shop. Lucy did not want to carry the doll on the way home and maintained a resentful silence. Once in the house, she yanked all the clothes off the doll and flung them aside. She took the ribbon from its head and pulled violently at the pale, yellow hair, until it stood in rough tufts.

‘Leg off,’ she said, her little hands tugging ineffectually at the doll’s limb. She looked at me. I sighed. Defeated, I prised the right leg out of its rubbery socket and handed the doll back to Lucy.