Читать книгу Indonesian Cooking - Dina Yuen - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеA Symphony of Surprising Flavors

In 1994, a few months before I opened my Honolulu restaurant, Indigo, my wife, Barbara and I traveled to Indonesia and Thailand on a serendipitous shopping and eating trip. Our plan was to find unique furnishings and architectural pieces that would create a sensual ambience for our diners. More than I expected, our travels turned out to be a revelation for my palate as well. This was my first trip to Asia—the first of many—and it greatly deepened my love affair with its glorious food. Barbara and I spent over a month traveling throughout the islands of Java and Bali. While hunting for treasures, we discovered the vibrant, multi-layered cuisine unique to this part of the world. From fiery hot sambals to spicy coconut-based curries, crisp banana fritters to creamy durian ice cream—each provided a symphony of delicious, often surprising flavors–many of which I later adapted into signature Indigo dishes.

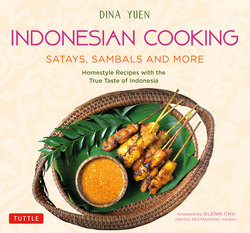

Within these pages, a culinary adventure awaits you. With Chef Dina as your expert guide, you can explore the planet’s largest archipelago—the fabled Spice Islands—and its distinctive cuisine in your own kitchen. Dina’s clear, easy-to-follow recipes capture the spirit of Indonesian cooking—a diverse, little known cuisine she makes accessible to anyone. Ranging from the familiar, such as Chicken and Beef Satay, Fresh Spring Rolls (Lumpia Basah), Indonesian Mixed Salad with Creamy Peanut Dressing (Gado Gado) and Traditional Nasi Goreng, to the more exotic, such as Spicy Lemongrass Beef (Daging Asam Pedas), Carmelized Pork (Babi Kecap), Grilled Swordfish with Fragrant Yellow Rice (Ikan Bakar dengan Nasi Kuning), or Tamarind Roasted Shrimp (Asem Udang Bakar), this collection of tantalizing recipes is certain to delight.

Dina not only shares her many years of cooking knowledge but clearly communicates her love of family and passion for food as well. In our memories, food is deeply rooted to those places and people we love. The Indonesian Cookbook celebrates food, its enticing flavors, tastes, and aromas, and the important role it plays in keeping us connected to friends and family.

Glenn Chu

Chef/Owner, Indigo, Honolulu

My Great Love of Indonesian Cuisine

Ever since childhood, I have equated food with love. Nearly every memory I have of gatherings with family and friends involves being around food. What could possibly be more important in life than great food and great company? My love affair with Indonesian cuisine began long before I even realized that’s what it was. Having been blessed with wonderful parents who were world travelers, I had the opportunity to live in and visit many countries. Indonesia was host to a good number of my childhood years, profoundly contributing to what would become my lifetime passion for cooking and feeding people.

Indonesia and I have a very special relationship; it is after all, the place where many of my childhood memories take place. During those formative years, my parents educated my sisters and me on the great importance of the art of travel and food. Naturally, this education included the appreciation of Indonesian cuisine. As a child though, I didn’t always realize how lucky I was to have certain experiences or to be in a certain place. It wasn’t until years later that I finally grew up enough to fully comprehend the priceless gift my parents had bestowed upon my sisters and me.

Every momentous occasion in Indonesia, whether it is a birthday, house warming, or office opening is celebrated with a Tumpeng. Tumpeng is a spectacular all-in-one feast of turmeric seasoned rice shaped into a gargantuan mountain top, with an assortment of side dishes that can range from the simple and inexpensive (fried chicken and soybean cakes) to the complex and extravagant (grilled seafood, potato cakes and a dozen other yummies). Tumpengan, or the day of Tumpeng, is the one day when all boundaries of race, age, class and any other distinctions are put aside to feast together, give thanks and pray together, celebrate together. An Indonesian superstition dictates that whoever manages to eat the very tip of the rice will enjoy good luck for years to come. I never did have a chance to eat the proverbial mountaintop at any Tumpengan but I can safely say that good luck allowed me to partake in many of those glorious feasts.

I have been very fortunate to have had the opportunity to travel the 17,000 islands of Indonesia, though I’ve yet to set foot on each and every one of them. From east to west, north to south, the world’s fourth most populous nation has an astoundingly vast array of indigenous cuisines to boast of, each as uniquely individual as its people and dialects. Masakan Jawa, for example, is the cuisine of eastern Java, predominantly the Surabaya area, famous for spicy salads and rich flavors. The fantasy island of Bali with all its lush greenery and untouched beaches, boasts a beautiful blend of sweet and mildly spicy roasted meats, showcasing the traditional methods of cooking in nature. Western Java offers two distinctly different cuisines, Betawi and Sunda, each with accents portraying Indonesia’s long cultural and political history.

Along with my parents and siblings, I became a seasoned traveler and eater, going from the finest, world class dining establishments in five diamond hotels such as Ritz Carlton, Four Seasons, Aman Resorts and Mandarin Oriental to frequenting hole-in-the-wall restaurants only locals have known for decades. I ate Indonesian Rijstaffel in its finest presentations on delicate China with linen tablecloths and I ate Es Campur and Bakmi Baso on the streets of Jakarta and Surabaya, (the latter experiences when my mother was not around as she would be terrified of my contracting some dreadful malady from dirty water). The duality of such opposites became an addictive drug to me, each experience offering its unique set of flavors, scents, sounds, and emotions.

In my later teenage years, I experienced many of the most painful and trying moments of my life, losing my beloved grandfather and several other treasured family members. Those devastating losses shaped the course of my spirit and life irrevocably, often manifesting in the strangest of ways. In the kitchen, I began an insatiable quest for acute flavors, emotionally familiar aromas, recreating recipes that were the favorites of people I’d lost forever. Aside from photo albums that were sometimes too difficult to look at, the recipes were all I had left to feel their embrace, to hear their laughter and the happy noises of loved ones eating together. From those early years until today, food has become the only viable bridge between those living in the present and those who have passed on.

Every time I miss my grandfather (or my uncles, aunts and cousins) I begin to cook his favorite dishes, many of which were Indonesian. From classic Indonesian Mapo Tofu (Mun Tahu) to Chicken Rice Porridge (Bubur Ayam), I often spend hours in the kitchen, creating one dish after another, as a silent offering to someone I love, who happens to be a little far away. I chop garlic at lightning speed, laughing to myself as I hear their voices, “add more garlic…you can never have too much garlic.” On my hands and knees, I maneuver the stone mortar and pestle to grind the red chili peppers, watching the ghost of my aunt showing me exactly how to bend my arm to get the right pressure. And when I’m done cooking, when I’m done trying to make each dish a little better every time, I sit down with those loved ones around me today, sharing a wonderful home cooked meal. I give thanks for this new happy moment. For just a second, I close my eyes, I smell, I taste, and I am there again with the people who live in that most treasured place in my memory.

People who are unfamiliar with Indonesian cuisine always ask me “what is it like?” and I can only vaguely describe it as somewhere between Thai and Indian cuisine. It shares Thai cuisine’s penchant for the intensely spicy and salty, and India’s passion for rich curries. Really though, Indonesian food has its own unique range of flavors, ingredients, and techniques. Indonesian cuisine’s unabashed use of fresh herbs and spices (such as garlic, turmeric, shrimp paste, Kaffir lime leaves and galangal) contribute to dishes that are fragrant and flavorful.

To have a complete grasp of Indonesian cuisine, it’s imperative to understand that, from west to east, there are dramatically differing ingredients and techniques used in preparing meats, seafood, and vegetables. They stem from cultural history and traditions that existed long before modern day restaurants and fancy kitchens.

The beautiful island of Bali is famous for its fresh seafood, which is no surprise considering the local abundance. But Bali differs from the rest of the nation in its culinary treatment of fresh seafood and meats. The ever popular Bumbu Bali refers to any seafood or meat that is first marinated in a rich coating of sweet soy sauce and a garlicky thick, red chili paste before grilling on an open air flame. What results is a succulent, sweet, and savory grilled meat or seafood dish with just a hint of spiciness.

Moving slightly west to the east coast of the main island of Java, is the metropolitan city of Surabaya and its surrounding neighbors, such as Malang. This eastern region is famous for its incredible desserts, including: old fashioned mocha cakes whipped up by grandmas in batik sarongs using butter; sweet and fluffy breads that make you forget all about calorie counting and the kind of ice cream cakes I had as a child that make me now desperately wish I could turn back the hands of time.

On the west coast in the capital city of Jakarta and its neighbors, we find yet another kind of indigenous Indonesian cuisine—rich curries simmering in old cauldrons, spicy fruit salads made with stone mortar and pestles and dishes that reflect the influences of foreign migrations into Indonesia in centuries past.

It’s the commitment to using fresh ingredients, organic ingredients before the word organic became a fancy marketing gimmick; it’s the fearless and bold use of herbs and spices and the relentless clinging to traditional methods that all come together to shape this spectacular country’s unique and exotic foods.

Happy Cooking

Dina Yuen

A Few Tips and Techniques

The best way to ensure success in creating delicious Indonesian cuisine is getting organized and staying that way. Many of the tools and ingredients necessary in an Indonesian kitchen are now widely available in all Asian grocery stores and even in many Western markets. It’s always a good idea to start off by investing the appropriate amount of time, effort, and money to purchase good quality ingredients and tools so that you don’t end up wasting time or money.

Using a Mortar and Pestle Though we have modern day conveniences, such as food processors and blenders, there is nothing quite like using traditional tools. Out of all the mortar and pestles in existence, the Indonesian stone version is my absolute favorite. While using this tool does require a little physical exertion, the unique textures and flavors that result are well worth the effort. Make sure that the surface of the mortar is dry before placing the ingredients on it. When working with garlic or fresh chili peppers, a helpful trick is to sprinkle a little salt and/or sugar on top before mashing. The salt and sugar act as an abrasive helping to break everything down. Never pound the pestle in an up and down motion like you would with a meat pounder because of splattering. The Indonesian pestle has a curved structure, designed for angled and long strokes. Be firm with each stroke of the pestle against the mortar, almost as if you’re dragging the ingredients along while firmly pushing down. You should also use a spoon to scrape the ingredients into the middle every so often so that you don’t end up with a mess around the perimeter of the mortar. When finished, simply rinse the mortar and pestle under warm water and allow to air dry.

Using Fresh Ingredients I think it’s important to use fresh ingredients whenever possible. In modern times, it can be tempting to purchase what appears to be easier alternatives in the form of canned, jarred, or frozen goods, but authentic Indonesian cuisine demands fresh ingredients to produce its array of complex flavors and textures. There are, however, certain preserved ingredients that are acceptable as substitutes for particular recipes without seriously compromising the integrity or quality of the dish. Ingredients such as coconut milk and palm sugar (gula jawa) are easily found in Asian markets in canned or packaged forms.

Working with Coconut Milk Coconut milk has a much lower burning temperature than many other liquids. When cooking with this rich liquid, remember to keep a close watch on it so it doesn’t burn or boil over in the pot. Whether you’re cooking a curry or a stew, it’s important to stir often to avoid any ingredients sticking to the bottom of the pot or wok. If you use coconut milk to cook rice in a rice cooker, make sure to mix the rice gently with a wooden or plastic spatula even after the rice cooker says it’s done cooking. After mixing the rice, allow it to sit on the cooker’s warm setting for at least another 10 to 15 minutes before serving.

Working with Turmeric Turmeric is one of Indonesian cuisine’s major ingredients, both in its fresh root and powdered forms. It can be difficult to find fresh turmeric in Western countries so I’ve substituted the powder form in these recipes. Similar to working with coconut milk and rice, when using turmeric in rice, you must mix the rice gently to spread the color and flavor of the turmeric evenly before and after the rice has cooked.

Stir-frying The most effective technique for ensuring great stir-fry dishes is to work with a large wok and wooden spatula. Gas stoves provide the optimum cooking situation because the heat will remain consistent, allowing you to stir-fry the ingredients quickly without burning. When stir-frying, always move the ingredients around with the spatula often and quickly. If you’re working with an electric stove, you’ll have to compensate for the lack of consistent heat by allowing the ingredients to remain at rest for longer periods of time between the actual stir-frying.

Stir-frying Rice or Noodles Working with large quantities of rice or noodles is no easy task. Without proper technique, you may end up with mushy rice and noodles that will fall apart. Borrowing from the general rules of stir-frying, start with a large wok and wooden spatula. The key to successful stir-fried rice and noodle dishes is to not mash these ingredients while cooking, but rather use the spatula to fold them over. Use your entire arm and elbow movement as opposed to a wrist action when stir-frying heavy ingredients. Don’t be afraid of scraping the wooden spatula all the way down into the bottom of the wok to ensure that no parts of the ingredients are left to burn while other parts are sitting uncooked on top. If you use your entire arm power rather than wrist movements, it will yield the broader strokes that fold over the rice and noodles.

Deep-frying Whatever you’re deep-frying, make sure to start with enough vegetable oil to cover the ingredients. I like using either a wok or deep pot for deep-frying. Once you get the hang of this technique, you’ll never have to worry about burnt or uncooked food again. Just remember a few simple rules. If you’re deep-frying something like chicken with bone-in, then you don’t want to set the temperature of the stove to anything higher than medium high and possibly lower than that if your stove has a strong heating capacity. Higher heat will result in browning and crisping exteriors quickly while interiors will remain relatively raw. A higher heat setting works for deep-frying dishes such as Banana Fritters (Pisang Goreng) because the banana is already cooked; you just want to brown and crisp the outside batter, which takes relatively little time. Conversely, an ingredient as substantial as chicken breast needs much longer cooking time at lower temperatures to ensure that the inside is thoroughly cooked while the outside doesn’t burn too quickly. Also remember to allow the oil to come up to temperature before dropping in any ingredients otherwise you’ll end up with a soggy, oily mess. A good way to check if the oil is hot enough is by sticking a chopstick in the oil. If little bubbles surface around the chopstick, the oil should be hot enough.

Getting the Most Out of a Lime We’ve all experienced the great annoyance of buying limes that looked beautiful at the market only to get home and find that they’re dried up. A good technique to getting the most juice out of a lime is to either microwave the lime for about 20 to 30 seconds or run it under hot water for a minute, then roll it around firmly with the palm of your hand on a cutting board. This yields a spectacular amount of juice from good limes and at least something out of a bad one. Save your taste buds and stay far away from all the pre-bottled versions, they’re just not a good substitute.

Keeping Herbs Fresh By now, you realize how strongly I advocate using all fresh ingredients and there’s no aspect of Indonesian cuisine that warrants that rule more than using fresh herbs. Most of us don’t have the time to shop more than once a week so I use this technique to save time and cost, and prevent waste. As soon as you get home with fresh herbs, rinse each type in cold water and drain thoroughly. Using either a paper towel lined basket or baking sheet, spread the herbs gently and pat dry with another paper towel. Allow them to air dry completely for at least several hours up to overnight. Once they are thoroughly dried, store each type separately in zip lock bags lined with new sheets of paper towels.

Useful Tools and Utensils

Having the right tools for the job makes cooking a joy. Here are some items that I think make the whole Indonesian cooking experience easier, more enjoyable, and produce tastier results. Typically, Indonesian kitchens are simply outfitted, but it’s difficult to argue that some modern conveniences can save time and hassle without affecting the quality of the food.

Asian Butcher Knife/Cleaver As cliché as it might sound, it’s true that a dull knife is far more dangerous than a sharp one. I have experienced this myself, cutting my fingers in nasty accidents due to dull, low quality knives. I’m forever loyal to my Asian butcher knife with its huge rectangular shape and seemingly invincible steel heft. I know some of you may not be familiar or comfortable with this type of large knife but once you get used to its size and weight, you’ll find it to be an extremely versatile and useful tool. I use this for everything from mincing garlic to cutting vegetables and chopping through all types of meats with bones. These knives can be purchased inexpensively at Asian grocery stores.

Asian Strainers There are many types of these strainers, the good ones feature some type of mesh-looking wire material in a rounded shape with a long wooden handle attached. Asian strainers are great for picking up noodles, vegetables, and anything you’re either boiling or deep-frying that need to be drained. Make sure to purchase one with a long handle; it will save your skin from potential hazards while removing whatever you’re cooking from its liquid. This tool beats using tongs for picking up noodles or something like shrimp chips where you’re cooking a large quantity and need to drain them quickly. Certain recipe such as the Iced Coconut Cream with Jellies (page 114) require a particular kind of strainer which can be difficult to find in Western countries. The closest tool would be the ladle strainer, which looks just like a regular metal ladle but has small round holes.

Cutting Board An often-overlooked tool in kitchens is a strong, sturdy cutting board. Many Indonesian kitchens use large wooden butcher blocks as cutting boards, which is a great tool if you have a lot of space to thoroughly clean it and don’t mind their weight. My preference is a large cutting board made of plastic or silicone with at least half an inch of depth. A good sized plastic cutting board will serve as a multi-purpose tool because you can use it for mincing herbs and spices; cutting vegetables and fruits; or chopping meats and seafood. Unlike wooden boards, you don’t need to worry about bacteria seeping through its pores or the wood warping from water. Always clean your cutting boards with soap and hot water, allowing them to air dry thoroughly.

Food Processor In lieu of a traditional mortar and pestle, a modern day food processor is a fabulous tool. Besides grinding all types of herbs and spices that produce many of Indonesia’s sambals and pastes, these nifty gadgets are a huge time saver when it comes to grinding all types of meats and mixtures. Were you so inclined, you could of course do everything the old-fashioned way and manually chop meat into its grounded state. While markets nowadays offer pre-ground meats, some recipes call for further fine grounding and mixing with other ingredients, which food processors complete in seconds. Like any other tool, investing in a good quality food processor will save on costs in the long run—a sturdy one should last for many years if not several decades.

Meat Pounder This is a tool that is not often discussed in Indonesian cooking but I have found it to be a great way to make perfectly cooked meats. For example, the recipe for Banjar Chicken Steak (page 65) calls for pan-frying chicken breasts. You can’t always get perfectly shaped chicken breasts; one side is often much thicker than the other which means that cooking will be uneven. One side will be completely done cooking while the other is still raw on the inside. Using a meat pounder solves this issue easily. When using a meat pounder, I like to lay the meat across a plastic cutting board and cover it with a large piece of plastic wrap to protect from splattering bacteria all over the kitchen, other ingredients, and myself. With this method, you can then pound on the meat to whatever desired thickness without worrying about raw meat and its juices flying all over the place.

Metal Ladle A metal ladle with a long handle is necessary to work with soups and certain noodle dishes. Purchase one that’s a good size with a sturdy handle, preferably one that is metal throughout or those with an outside layer of wood on the handle. Plastic ladles are never used in Indonesian cooking unless for serving desserts or cold dishes, and wooden ladles can often impart a strange flavor to the dish so should be avoided as well.

Mortar and Pestle (Cobek or Ulek) A traditional Indonesian mortar and pestle is one of the greatest kitchen tools of all time. Unlike those from other countries, Indonesia’s version is flatter and more open on top, like a plate with rounded edges rather than an enclosed bowl-like contraption. The pestle is also shaped differently, having a distinctive curvature for ease of grip allowing for Indonesia’s unique technique of grinding. Made of basalt stone, the Indonesian mortar and pestle allows herbs and spices to have optimum surface area contact with the rough stone that produces the delicious and spicy sambals with their smooth texture. Typically heavier than their Thai or Mexican counterparts, the Indonesian mortar and pestle is more readily available in Western regions in recent years. These should never be washed with soap of any kind but rather rinsed thoroughly with warm water and allowed to completely air dry before storing.

Rice Cooker One of the easiest tools to use in an Indonesian kitchen is a good quality rice cooker. I can’t imagine any modern day kitchen without one; it saves on time, cleanup, and effort while cooking perfect, fluffy rice. You should follow the general instructions of your particular rice cooker though my personal rule of thumb for perfect white rice is 2 parts water to 1 part uncooked rice. These days you can find all types of rice cookers with price tags ranging from as low as $15 to as high as several hundred dollars. For the average home kitchen a rice cooker somewhere in the middle range does just fine. It does pay in the long run to invest in at least a decent rice cooker rather than the cheapest one because this is a tool that should last you for years. The great thing about modern day rice cookers is that you can just set the rice to cook and it will stay warm from at least a few hours to a few days (for the more expensive models) and you never have to worry about burning the rice or water over-flowing.

Wok (Wajan) One of the most invaluable tools in an Indonesian kitchen is of course, the wok. The type of wok you need depends on whether you have an electric or gas range. Home cooks with gas stoves are lucky because nothing surpasses the quality or speed of a real fire. However, with the proper tools, you can create great dishes on either type of stove. If you have a gas stove, you can use the traditional and original cast iron wok with its rounded bottom. Make sure to find one with a long, sturdy handle on one side rather than the two short handles on either side. Unless you’re a professional wok chef, working without a handle will be extremely difficult. Depending on the exact shape of your gas stove, you may also need a wok ring to stabilize it. For those of you with an electric stove, you’ll do best with a carbon steel wok with a flat bottom so it can sit properly on the range. This too should have a long, sturdy handle. When purchasing a wok, don’t be afraid to look it over carefully and run your hands all over it, roughly yanking at the parts to ensure that it is in fact, a sturdy model. There are plenty of people who have all types of fancy methods of caring for a wok but most of those steps are really unnecessary for modern day woks. If you’re handling a brand new wok, simply pour a few tablespoons of vegetable oil on a paper towel and rub thoroughly all over the inside of the wok. Place the wok on the stove over high heat until smoke rises. Tilt the wok in every direction so all parts of the wok come into contact with the heat. Do this for just a couple of minutes. Remove the wok from the heat and cool. Once it has cooled, rinse thoroughly under warm water and air dry. Once you begin using the wok regularly, make sure to use a soft sponge to clean with soap and water. Never use harsh bristles or any type of steel wool sponge. When working with the carbon steel type woks, also make sure to use only wooden or silicone spatulas and never metal ones that can scrape and ruin the wok.

Wooden Spatula With many Indonesian recipes calling for stir-frying techniques, it’s essential to have at least one very sturdy and good quality wooden spatula. These come in various shapes and sizes; any of them are fine as long as they feature a long enough handle, a wide enough surface area and are sturdy.

Buying the Right Ingredients

I’ve always been a proponent of fresh and authentic ingredients in order to recreate the dishes of Indonesia. The following are some key ingredients for the typical Indonesian meal. Although these ingredients are slowly finding their way into many grocery stores, I have provided substitutes for those that are still difficult to find.

Bird’s-Eye, Chili Pepper (Cabe Rawit) Amongst the spicier peppers, coming in at 100,000 to 225,000 on the Scoville heat scale, these peppers are typically harvested when they are about one-inch long and range from a bright green hue to a beautiful, deep red when mature. As with all peppers, the heat is found most intensely in the seeds, although this pepper packs a punch just in its skin alone. Widely used in stir-fries and curries, these tiny peppers are indispensable to Indonesians when making chili pastes, or sambals. Traditional methods of making sambals involve using a mortar and pestle to mash bird’s eye chili peppers with fresh garlic. You can find these in the fresh produce section of a well stocked grocery store. You can substitute Dry Ground, Chili Peppers (see this page) if you can’t find them fresh.

Coconut Milk (Santen) Coconut milk is indispensable to Indonesian cooking. A large variety of coconut milk can be found in western markets these days, which include brands from Thailand, Vietnam, and even Cuban companies based in Miami. They are found in cans, occasionally in cartons, and in powder form. Any of them are fine to use in Indonesian cooking. You can find coconut milk in the Ethnic food sections of most grocery stores. It will keep for a few days in the refrigerator if covered.

Coriander, Ground (Bubuk Ketumbar) A vital ingredient in many stews and soups in Indonesian cooking, ground coriander has a somewhat citrusy and nutty flavor. Not a spice with a particularly overwhelming fragrance or taste, it’s easy to overlook its use until you notice that something isn’t quite right in a dish. Ground coriander is one of those subtle ingredients that serves as a key accent in the balance of complex flavors without screaming its presence aloud. Commonly sold in both western and Asian markets in either small bottles or plastic pouches found in the spices section. Ground coriander should be stored in a cool, dry space.

Dry Ground, Chili Peppers (Bubuk Cabe) Several species of chili peppers are used in the production of the dry ground version, depending on the nation of origin. Red bird’s eye chili peppers are often used to make this spicy condiment. The peppers are dried out under the sun, then either mashed up into the powder or ground up using a food processor. Dry ground chili pepper is a fantastic substitute for the fresh peppers not always available in the West. These days American supermarkets carry some type of Dry Ground Chili Pepper. Chinese versions typically use a wok-roasted method, lending a slightly burnt aroma, while Indonesian, Thai, and Vietnamese versions are spicier and smoother in texture. All Asian grocery stores carry various versions of Dry Ground Chili Peppers. Store in a cool dry space.

Dried Shrimp Paste (Terasi) These days it seems that every Southeast Asian nation has produced its own version of dried shrimp paste, each with an individual texture, odor, and flavor. In general, they can be interchanged in recipes, but try to use the Indonesian version when cooking Indonesian cuisine. Indonesian shrimp paste is known as terasi, which is typically sold in small blocks covered in a plastic wrapping. Shrimp paste (and the Malaysian shrimp paste known as belachan) is so tightly packed that, unlike the Thai version of shrimp paste, it is a hard block that requires cutting with a knife before using. Boasting a beautiful, dark aubergine hue, shrimp paste has the strongest, most full-bodied aroma when cooked compared to its other Asian counterparts. Indonesian shrimp paste is not always readily available in the West so, when necessary, substitute with the more easily found Thai shrimp paste, which typically comes in a white plastic tub with a red cap.

Galangal (Lengkuas) In the same family as the ginger root, galangal is often confused with ginger or turmeric due to their similar exteriors. Galangal boasts the lightest skin amongst the root family, though unlike ginger, it typically has darker, thin brown rings along its root. On the inside, galangal is almost always the lightest in color amongst the roots, with a soft creamy yellow color. It is also one of the toughest roots to work with, requiring either a very sharp or heavy knife to cut through. Galangal has a soft camphor-menthol aroma and is used in Indonesian soups, lending a more intense heat similar to ginger. Galangal can be found as whole roots in Asian grocery stores and often in its powder form. Stored tightly in resealable plastic bags, it can be kept in the freezer for several months.

Garlic (Bawang Putih) Indonesian cuisine would not be as profoundly rich or aromatic without garlic. Used extensively throughout Indonesia, garlic is one of the most popular ingredients in the country. Its most typical use is either in a finely minced form for cooking or mashed as part of sauces and sambals. Garlic’s role in Indonesian cuisine is varied, ranging from dominant to subtle. Garlic cloves are available everywhere in both western and Asian supermarkets in the produce sections. They should be stored in a cool, dark place and allowed to breathe. They can be frozen but fresh garlic is optimal.

Ginger (Jahe) Ginger root finds it origins in Asia and is central to Indonesian cuisine. Similar in appearance to turmeric, ginger is a hard root with light to medium brown skin. Its flesh differs from turmeric though, with a light golden color when at its peak stage. Ginger’s pungent, spicy base lends heat to stir-fries and soups, in addition to its delicate aroma. Ginger is used in savory dishes and also in desserts and warm teas. Young ginger imparts the greatest amount of sweet juice while stale ginger should be avoided. You can tell if ginger is too old by pressing firmly on it; if it is too hard and doesn’t give off a faint aroma, it is probably stale and will taste bitter. It can typically be found in the produce section of grocery stores. They can be stored in the refrigerator in a paper bag for a few weeks. They can also be peeled and sliced and stored in a jar of sherry.

Kaffir Lime Leaves (Daun Jeruk Purut) These leaves add an unmistakably fresh aroma to Indonesian cuisine. Used in many soups and stir-fries, kaffir lime leaves are unique and impossible to substitute. The leaves are used both fresh and dried. Stored in the freezer in air tight bags, these leaves can last a remarkably long time, retaining their flavor and scent. They can be found in the frozen food section of Asian grocery stores or purchased through online retailers.

Lemongrass (Serai) In the past decade or so lemongrass has become more widely available in the western hemisphere. This has made creating authentic Indonesian dishes much easier. In western supermarkets, lemongrass is usually available in the produce section in an already finely minced paste sold in plastic tubes. In Asian supermarkets, lemongrass comes in a larger variety of forms, ranging from its entire original stalk to finely minced and even thinly sliced (the latter two usually packaged in small plastic tubs). The refreshing and light citrus essence of lemongrass is difficult to mimic, but some cooks will substitute with lime zest. They will store in the refrigerator for up to three weeks, or can be frozen for up to 6 months without losing their flavor.

Limes (Jeruk Nipis) An easy to find ingredient, limes are a staple in Indonesian cuisine, used in cooking and in food presentations as a garnish. Bursting with freshness, limes exert a tangy bite, a welcome addition to heavier dishes or hot soups. Most Indonesian stews and soups arrive at the table with lime wedges on the side, brightening the complex flavors of these meals. Limes are also used in fresh sauces and condiments as opposed to their mass production counterparts that use vinegar to cut costs. A good lime should have a smooth texture, a uniformly green vibrant color and should be somewhat soft to the touch. Found in the fresh produce section of your grocery store, they will stay good for a week or two before they start to lose their flavor. They can’t be frozen.

Nutmeg (Pala) Indigenous to the Banda Islands of Indonesia, nutmeg is widely used around the world, particularly in western desserts. Few realize its roots are in fact in Asia, from a species of the evergreen tree that produces both nutmeg and mace. Lending a low-toned, aromatic fragrance and distinctive sweet base, it is used sparingly in Indonesian cuisine as a subtle but key accent. Many Indonesian dishes influenced by the Dutch colonization feature nutmeg as an important ingredient. When recipes call for nutmeg, use either freshly ground nutmeg or already ground nutmeg. It’s readily available in the spice section of grocery stores. Store in a cool dry place.

Dried Egg Noodles, (Bakmi Kuning) As its names suggests, this variety of noodles is made from eggs and wheat. Influenced by the Chinese population, egg noodles are commonly used in Indonesian cooking and have become so popular through the generations that large business empires of pre-seasoned noodles and restaurants have been founded upon this one larger than life ingredient. In the West, Asian grocery stores carry a large variety, though the Chinese brands tend to dominate. Any type is fine for Indonesian cooking, though my personal favorites are those that closely resemble the ones found at my favorite noodle restaurant in Indonesia these are curly and come packaged in small rounds. These dried egg noodles are not to be confused or substituted for the kind typically sold in Western markets because these have a completely different taste, texture, and size.

Misoa (Somen) Thanks to the Chinese influence in Indonesia, Misoa noodles or somen, are a popular noodle that’s used mostly in soups. Misoa are white, thin noodles boasting a very mild, gentle flavor, and soft texture thanks to the stretching it undergoes during production. When cooking with Misoa, it’s important to remember that these noodles absorb so much liquid and so maintaining a proportion of the noodles and soup is crucial to the success of the dish. Commonly sold in Asian markets along with other dry noodles and usually near the soba buckwheat noodles, it is typically packaged in already portioned bunches.

Rice Stick, Noodles (Bihun) Rice stick noodles are known in the West by several names, such as thin rice noodles, rice vermicelli, or chow fun. Made from rice, Bihun is very different from the heavier and richer egg noodles. A wide variety of rice noodles are sold in Asian markets and it’s important to purchase the right type. Some brands from China produce rice noodles that appear slightly curly and in my experience, those yield flavorless and rubbery noodles. The ones to look for have a uniform off-white coloring and are typically packaged in large bunches with a smooth, even texture throughout. Do not confuse rice noodles with the clearer mung bean noodles, (known in Indonesia as Soun) or the larger sized varieties of Vietnamese rice noodles used for Pho.

Cellophane, Noodles Also known as glass noodles, these are made from the starch of mung beans (or other bean products) and, as the name implies are glassy in appearance. They are highly absorbent and will pick up the flavors of the dish. Be careful when cooked with oil because the absorbent qualities can make them greasy.

Indonesian Palm Sugar (Gula Jawa) This type of palm sugar is also known as Gula Merah, or red sugar, and is one of the most misinterpreted ingredients in the West. This is a dense sugar derived from the palmyra palm but is extremely different from palm sugars typically sold in western markets. While the western varieties of palm sugar are also hard and dense, they are a light to dark brown in color and less moist than Javanese sugar. Javanese sugar has an earthy aroma and deep sweetness with a color closely resembling molasses. In Asian markets in the West I’ve only encountered one type of Indonesian Javanese sugar sold and those are in cylindrical shapes covered in white plastic wrap with the words “Gula Jawa” printed on the packaging. This wonderfully rich and full-bodied sugar is unique to Indonesia, its flavor and moist, crumbly texture has no imitators. When recipes call for Javanese sugar, it is best not to substitute. These days most Asian markets carry it, along with online Asian grocery stores. When absolutely necessary, substitute with dense, tightly packed dark brown sugar. Store in a cool dry place.

Peanuts (Kacang) Recipes calling for peanuts in Indonesian cuisine typically refer to the unsalted, raw version. In Indonesia, the raw nuts are widely sold in their original shells, while in the West, an easier to use the dry version that’s readily available in plastic pouches already de-shelled. Many Indonesian dishes and condiments feature a bold, nutty flavor, making this an indispensable ingredient in an Indonesian kitchen. When working with the raw peanuts, it’s important to dry roast them for a few minutes in a wok or heavy pan until they are lightly browned before going on to combine them with other ingredients. They store easily: three months in a dry place; six months in the refrigerator; indefinitely if wrapped in plastic and placed in a freezer.

Rice (Beras) No other ingredient can be a more vital in Indonesian cuisine than rice. Its raw form is known in Indonesia as Beras, while after cooking it is referred to as nasi. Indonesians love their rice, often eating the popular carbohydrate as many as three times a day. Though its usage can be found in the infamous dishes of Nasi Goreng (fried rice) and Chicken Porridge (Bubur Ayam), regular white rice reigns supreme as the staple of meals. The inclusion of white rice in meals is what allows Indonesians to enjoy so many savory and spicy dishes and condiments. Stews, curries, and stir-fries are also all eaten with white rice. In fact, the only time white rice is left out of a meal is when noodles take its place as the main starch. Found in the grains section of the grocery store, it should be stored in a cool, dry place.

Rose Syrup (Sirup Mawar) Rose syrup is an important ingredient in making many Indonesian drinks and desserts. With no remotely similar products anywhere in the world, its presence in recipes cannot be replaced. Boasting a deep red hue and a luxuriously thick consistency, rose syrup carries the fragrance of its namesake and translates into a distinctive floral sweetness on the palate. Produced only in Indonesia, a few brands of rose syrup can be found in Asian markets, though the Indonesian kind should not be confused with varieties from India. Those from India possess a completely different color, texture, and flavor that cannot be used in Indonesian cooking. All Indonesian brands selling rose syrup have unmistakable packaging—clear glass bottles that show the rich redness of the syrup and labeled “Rose Syrup” and/or “Sirup Mawar.” Keep in a dry place or refrigerate.

Sambal Oelek When cooking Indonesian cuisine outside of Indonesia, ready-made Sambal Oelek is an invaluable ingredient that adds a tangy spiciness and a rich texture to dishes because of the seeds. Traditionally made with red chili peppers, Sambal Oelek typically has salt, sugar, and vinegar in it. The most widely available types are sold in clear, plastic bottles with bright green caps. All versions of Sambal Oelek are clearly marked with this name and should not be confused with the large variety of other spicy condiments such as sambal badjak or sambal terasi, many of which are sold side-by-side in Asian grocery stores. Using the Indonesian version of Sambal Oelek is preferred, however, it can be difficult to find in American markets. Substituting any Thai or Chinese version is fine as long as the product is clearly marked with the words “Sambal Oelek.” Store in the refrigerator after opening.

Shallots (Bawang Merah) Of the onion family, shallots are mistakenly believed to originate in Asia, this is not surprising considering its wide usage in most Asian cuisines. In Indonesia, shallots are commonly used both in cooking and in the popular condiment, Acar. With a milder and sweeter flavor than regular onions, shallots add a subtle sweetness to dishes, as well as lending a chunkier texture in most of the pastes that are the foundation of many Indonesian stews, curries, and stir-fries. Shallots are readily available in the produce sections of both western and Asian markets. They keep fresh for a couple of months if stored in a dry area.

Sweetened Condensed, Milk (Susu Manis) Used sparingly in drinks and desserts, sweetened condensed milk has found popularity throughout Indonesia. Produced from cow’s milk that has sugar added and water removed, condensed milk has a thick, molasses-like consistency with a creamy, light yellow color. Richly sweet, this ingredient is used mostly as a drizzle over Indonesian desserts and as a sweetener in iced beverages or hot coffee. Sweetened condensed milk is easily found in both western and Asian grocery stores, sold in cans that can remain fresh in the pantry for years if stored unopened. Once opened, it’s best to transfer the condensed milk to a squeeze bottle to stay fresh longer in the refrigerator and for ease of use.

Tamarind Concentrate (Asem) Indonesians use large amounts of tamarind in many dishes, primarily in soups. In earlier years, fresh tamarind pulp was used to flavor dishes but these days it’s easier to use the concentrated version that’s readily available in Asian markets as well as some western stores. Tamarind lends a piquant sourness to dishes, along with a beautiful, rich brown hue. Tamarind concentrates available in the West possess a thick consistency similar to tomato ketchup, allowing for a thicker consistency when used in soups and stir-fries. More powerful than lime or lemon, the unique flavor of tamarind should not be substituted. It can be kept covered in a refrigerator for up to a year.

Soy Sauce (Kecap Asin) A very familiar product in the West, regular soy sauce has become a staple in most American supermarkets. Used frequently in Indonesian cooking, regular soy sauce is an essential part of an Asian pantry. Most soy sauce varieties across Asia have the same consistency and salty flavor so there is no issue in substituting one brand for another. Asian grocery stores in the West carry a large variety of soy sauce brands while Western markets tend to feature Japanese brands such as Kikkoman. My personal favorite line of soy sauces is from the Lee Kum Kee brand, they have a large variety that includes low sodium options and different experimental textures for home cooks who are already familiar with Indonesian cuisine.

Sweet Soy Sauce (Kecap Manis) Sweet soy sauce is another ingredient that is constantly found in Indonesian cooking. Less salty than regular soy sauce, sweet soy sauce is thick and black with a rich sweetness. Used in both cooking and as the main ingredient in many sauces, several varieties of sweet soy sauce can be found in Asian markets. Good-quality Indonesian sweet soy sauce includes brands like Cap Sate and Kecap Bango. However, the Indonesian brands can often be difficult to find so, when necessary, substitute with the easily found Lee Kum Kee brand of sweet soy sauce.

Tempeh In recent years, Tempeh, produced from nutrient and fiber rich soybeans, has gained popularity in the West as a protein super food. Indigenous to Indonesia, a natural culturing and fermentation process condenses soybeans into a cake-like form making Tempeh. This unusual ingredient can be easily found in the produce section of most western markets as well as Asian stores. It can keep in the refrigerator for a week or so; if frozen it can be kept for six months.