Читать книгу Secret Weapons of Jujutsu - Don Cunningham - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление| Preface |

Like so many others of my generation, I was fascinated by the various martial arts movies and television shows which were quite popular during the 1960s. Maybe this was one of the reasons I took up judo training. Imitating my adventure show heroes, I wanted to be able to calmly defend myself with a few quick practiced moves, disabling even the most dangerous villains. During those early years practicing judo after school at the local Y.M.C.A., I never dreamed that this endeavor would become a lifelong pursuit or the places my practice of this sport would eventually take me.

One the benefits of my early telecommunications career were the frequent business trips required to meet with the engineers at the headquarters office of the Japanese subsidiary where I worked. In addition to the opportunity to view modern Japanese culture firsthand, I was also able to once again take up my study of judo in the country where it had all started so many years ago. Practicing judo at local Japanese judo dojos and participating in the frequent tournament competitions after work and on weekends, I met many new friends who shared my interest in judo as well as in other Japanese martial arts.

For a short while I also took up the practice of kendo, or the Japanese art of fencing with bamboo swords. Unlike the more modern sport aspects of judo, though, kendo is strongly influenced by traditions which date back to the more classical martial art styles. Although not as physically demanding as judo, the practice of kendo has many more facets derived from the etiquette and history of classical Japanese martial arts. I became fascinated with the samurai sword and developed a new appreciation for this beautiful, but very definitely lethal weapon and the culture which surrounded it.

I found myself becoming more interested in learning about the samurai culture which was so much a part of Japanese historical tradition. I became intrigued with the subject, reading as much as possible about Japanese history and the crafts of this period. I started seeking out those who were associated with the very few schools which still taught Japanese swordsmanship and the ancient combat styles. I was particularly interested in jujutsu, the unarmed fighting styles which were the forerunner of modern-day judo.

FIGURE 1. Visiting the Kodokan Judo Institute’s International Judo Center in 1988 in Tokyo, Japan.

As part of my developing obsession with early Japanese culture, I started collecting artifacts from the Edo Period, searching antique stores whenever the opportunity presented itself. For the most part, I was caught up in the fascination with the Japanese samurai sword, the icon of the warrior class, and tried to educate myself as much as possible about the old swordsmiths and the products of their craft. It was part of this activity that I began to read many of the translated writings left by the more educated members of this period. Despite my impression of the dangerous times and stoic individuals who lived back then, I was surprised to find that many held the indiscriminate use of the sword in disdain, preferring much less violent measures whenever possible.

This was definitely in direct opposition to the plot of the many popular samurai shows, called chambara, which were broadcast nearly daily on Japanese television. Like the quickdraw experts featured in the many low-budget westerns I often watched as a child, both the good guys and the bad guys in chambara shows were quick to draw their ever-present sidearm in nearly every confrontation, leaving numerous dead or dying victims strewn about in the street in their wake. I must admit that I was a big fan of chambara shows. While the fast action and drama was definitely the major attraction, though, the frequent swordplay conflicted with much of the actual historical research I found.

One afternoon while surfing the television shows on the set in my Japanese hotel room, I came across a very interesting chambara series featuring Zenigata Heiji, a very unique character. Heiji was a goyoukiki, basically a poor non-samurai assistant working for the higher ranked police officials in Edo. Heiji had a remarkable ability to throw heavy coins like bullets at criminals he was trying to disarm and capture.

Unlike his more swashbuckling counterparts, though, Heiji demonstrated a deep-seated humanity, often feeling a degree of sympathy for the same criminals he so frequently encountered. Heiji was not a member of the samurai class. In fact, he seemed to resent those who were, especially if they occasionally abused their rank and power. Although he detested crime, Heiji did not hate criminals. This often gave him a sense of justice tempered with kindness and respect which was not commonly found in the more violent chambara series.

Constantly feed on information and gossip by his tall and easy-going companion, Hachigoro, Heiji solved many of the crimes he faced based on his investigations and the application of intellect rather than by brute force. Never taking money or sometimes even any credit for his accomplishments, Heiji was often viewed as a failure by his superiors and acquaintances. A hero of the common man, though, Heiji had his personal faults as well, drinking and smoking tobacco heavily in many episodes. Yet he rarely resorted to gratuitous swordplay, preferring to use either the coins or a strange-looking iron truncheon, called a jutte, to disarm his opponents without bloodshed. The television series quickly became one of my favorites

Previously unfamiliar with this strange-looking implement, I found a jutte during one of my infrequent antique shopping expeditions. I bought it immediately, although I had no idea how such a weird looking device was actually used. It seemed nearly impossible that such a unimpressive looking weapon could possibly be used to disarm an experienced swordsman armed with a deadly samurai sword. However, I took my new treasure to judo practice one night at Asahi Judo Academy where I was a member and frequently practiced during my stays in Japan.

Located in Higashi-Hakuraku district near the center of Yokohama, Asahi Judo Academy is mostly known for the successful tournament records of their many junior high school judo competitors. The instructor and my friend, Asahi Dai, was also the judo instructor for the Kanagawa Prefecture Police Department, and many of his police friends often visit and help out with the evening judo sessions. It was to some of my acquaintances from the Japanese police that I wanted to show my new treasure, an authentic jutte.

The off-duty officers immediately recognized the jutte, eagerly demonstrating for me the many different disarming and restraining techniques using the unique implement. Although modern Japanese police no longer carry a jutte, they have a similar spring-loaded baton called a keibo. The keibo is often employed in their practice of modern taiho-jutsu, “body restraining” or “arresting art,” which is mandatory training for most of the regular police officers. I was surprised to learn that many of the jutte techniques from ancient martial arts styles were the basis for many current keibo techniques.

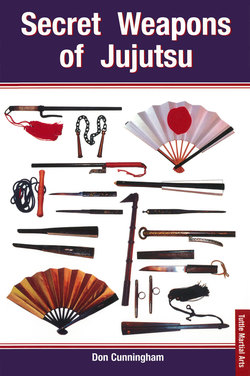

Armed with this new information, I began to research any historical information I could find about jutte and the associated techniques. I found that many of these were classed under the general heading of tetsushaku-jutsu. Instead of a jutte, tetsushaku-jutsu sometimes required a tessen, or “iron fan,” in the performance of the techniques. Now I began looking for more information about tessen techniques in addition to jutte.

Since then, I have accumulated a small collection of antique tessen and jutte as well as some excellent modern-day replicas. I have also read a number of historical references about the use of these implements. To my great fortune, I have been able to also obtain firsthand accounts of tetsushaku-jutsu from some of the hereditary teachers of classical Japanese martial arts styles, either in person or via correspondence. I have tried in this book to present as much of this information as possible for those who may share my interest in this rather esoteric aspect of traditional Japanese martial arts.

In appreciation

I would like to thank those who have encouraged and helped me in my quest for knowledge about jutte and tessen. There are far too many to name individually, but some deserve special note.

First, I would like to thank Asahi Dai and the members of Asahi Judo Academy for their patience with the sometimes confused foreign judoka, Matsuo Eriko and her parents for accompanying me on seemingly endless searches for jutte and tessen in the Nagasaki antique stores, the Shinto priest Matsuse Masashi and his family for our many discussions about tessen and jutte during our stay at his family shrine in Sasebo, Suzue Kazuhiro for his dedicated translation assistance, and Dr. Matsubara Fukumi and her students for allowing me to participate in their Japanese language meetings at North Central College and for their help with difficult kanji. I also want to thank Phillip Lech and Donald Andre for demonstrating the techniques in the photographs, Diane Skoss for her advice on navigating through the publishing maze, and Joseph Svinth for reading the preliminary draft and providing excellent comments.

Finally, I want to thank my wife, Lynn, and my family for putting up with my sometimes unusual obsession with Japanese martial arts and history.

Any errors are mine alone.