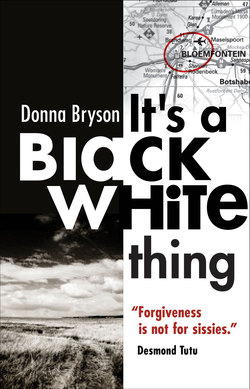

Читать книгу It's a Black-White Thing - Donna Bryson - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1. Songs of change

ОглавлениеIt started with singing that night in 1996. Billyboy Ramahlele feared it would end in a campus race war.

Ramahlele was new on the job – the first black man to head a hall of residence at what was then called the University of the Orange Free State. As head of the Kiepersol residence, he was a university-appointed father figure for the black students who had just begun to arrive in large numbers.

Those who lived on the campus (and for some, it was because they could not afford to live elsewhere) were housed in halls of residence, informally referred to as ‘reses’. These were more than just places to live: the reses have historically had great influence over the social, political and intellectual life of the entire student body at the university.

At this university, students apply to res committees for acceptance, often seeking places at the halls where their parents, or even their grandparents, lived and were moulded. The reses have age-old traditions – songs, mottos, secret rites and origin stories – almost a religious ritualism that is not out of place in the pious Free State. And in the past there were initiation rites meant to break down newcomers to the res in preparation for rebuilding them according to the values and expectations of their new community.

Residences have proudly borne names honouring figures like H. F. Verwoerd, the prime minister assassinated in 1966, who, during his eight years in power, oversaw the establishment of a South African republic, long an Afrikaner dream. Many black South Africans revile him as the prime architect of apartheid. Another res was named after Christiaan de Wet, the general who led Boer guerrilla fighters against the British in the 1899–1902 Anglo-Boer War. Historian Thomas Pakenham says that De Wet’s force ‘was not a majestic fighting machine, like a British column. It was a fighting animal, all muscle and bone’.1

Resourcefulness, independence, resilience – Afrikaners prize these qualities, which they believe helped them maintain their community against threats from powerful opponents in the past. And they can take a perverse pride in others’ depiction of them as narrow-minded isolationists. Afrikaner parents, Ramahlele says, would send their sons and daughters to the college at Bloemfontein from the province’s small towns and isolated farms, telling them to apply to this res or that res because it inculcated the values that they wanted their children to acquire.

‘Historically,’ he says, ‘residences were an extension of other institutions that were shaping an Afrikaner identity. There was government, there was the church, there was the education system – and universities were part of that: they were extensions for shaping what an Afrikaner is. The reason white students didn’t want black students living with them was, according to them, because they did not want their culture to be erased.’

Ramahlele was an ANC activist who, since the 1980s, had been pressing the university to open its doors to black students despite the prevailing apartheid laws. By the time he was appointed to the university staff in 1995 and took up his residence duties in 1996, apartheid was finally defunct, leaving some Afrikaners all the more fiercely determined to hang on to some semblance of power, like the outposts provided by the student halls of residence.

Ramahlele lived through and was a key player in a history that I, a foreign reporter who arrived in South Africa during apartheid’s waning days, had missed. He shared his history generously and vividly with me, helping me in my understanding of where South Africa has come from, and in my imagining of where it may be headed.

South Africa had seen its first all-race election in 1994, and Nelson Mandela had stood, tall and sombre, on the steps of Pretoria’s red sandstone Union Buildings, long a symbol of white racist rule, to take the oath of office as the country’s first black president.

‘Our daily deeds as ordinary South Africans must produce an actual South African reality that will reinforce humanity’s belief in justice, strengthen its confidence in the nobility of the human soul and sustain our hopes for a glorious life for all,’ Mandela told the nation in his 10 May 1994 inaugural address.2

At that point I was a young American reporter working on my first assignment in South Africa for the Associated Press. I had arrived in 1993, just on the eve of democracy, and would leave in 1996 to work in India, Egypt and the UK before returning for a second stint in South Africa from 2008 to 2012. In 1994 I had watched Mandela’s inauguration on television with a family in Soweto, one of the townships to which Johannesburg’s black maids, gardeners and other workers were removed during apartheid. The family had welcomed me into their home to report on what it meant for black South Africans to see Mandela become president.

I watched them raise their fists in the air as the first strains of the national anthem were played, sounding tinny from the speakers of a small TV set. They saw that Mandela, a tiny figure on the screen, had his hand over his heart. One by one, members of his audience in Soweto lowered their fists, opened their hands and placed them over their hearts. Mandela, South Africa’s master alchemist, was transforming a gesture of defiance into one of hope that a new nation was being forged which would command the loyalty of and be welcoming to all who lived there.

For black students at UFS in the mid-1990s, however, that welcome was cold. Many struggled financially and academically. Protesting students, who were demanding that the university write off their debts and offer more classroom support, toyi-toyied on the campus. Most white students had probably only been dimly aware of toyi-toying when the TV news brought anti-apartheid demonstrations into their living rooms.

Black and white students also clashed over seemingly petty issues, like whether to watch soccer or rugby on the res television. South African sports fans are largely divided along race lines, with black fans following soccer, and white fans choosing rugby. They may feel it’s natural for sport to be racialised, failing to realise the divide is rooted in history and stereotype, and is not something organic to the playing field.

Initiation rituals also rankled. In some reses, first-year students were expected to sit on the floor during house meetings, leaving the chairs to senior students. Initiation rites also included subjecting new students to all-night harangues, or forcing them to run errands for senior students.

Ramahlele was in his 30s when he arrived on campus in January 1996. He met black students who were his age, or older. Some had put in extra years of studying to prepare themselves for university after having undergone the inferior education to which apartheid subjected black people. Others had completed the traditional initiation rites of their ethnic groups, and expected to be treated as men. There were students who were husbands and fathers. Some had taken longer to finish high school because they had been involved in the struggle, and had spent time in jail because of their political activism. Former ANC guerrillas were among the students. And yet, Ramahlele says, here were young white students speaking to them as if they were labourers on their fathers’ farms.

‘In African culture, you respect your elders. And here’s a young Afrikaner boy telling you to sit on the floor,’ Ramahlele says. Some of those white students had been conscripted into the apartheid government’s army. Says Ramahlele:

You had black people, males in particular, who were fresh from the struggle, fresh from prison, fresh from detention, fresh from military training. And they’re thrown into the same residential area with whiteys. You also had Afrikaans boys who came from military conscription, who had been trained that a black man was an enemy. Trained also in other aspects of racism against black people. And here, for the first time, they meet at the University of the Free State.

Ramahlele explains that the university’s management team were not trained for these realities. ‘At that stage, every Afrikaner male had done military service,’ he says, referring to university managers who would have come of age before national service was abolished in 1992. ‘So, you had an ideological and a political conflict. The whole system of Afrikaner leadership was trained to see a black man with a different eye. And now you had black students who were resisting being seen in that way.’

Ramahlele says black students were too much of a minority to be elected to places on the committees that set the rules in the halls of residence. They felt vulnerable as the minority, he says, especially when the confrontations got physical.

The reses on one side of the campus became predominantly black. That area, Ramahlele says, was dubbed the ‘Bantustan’, an ironic reference to the nominally segregated black homelands established during apartheid. The white part of campus, Ramahlele says, was known as the Volkstaat.

Ramahlele’s res, Kiepersol, was integrated when he arrived but the white students left, and the black students who remained were particularly politicised. Some may have been drawn by the presence of Ramahlele, whose anti-apartheid activism was well known.

Ramahlele sees himself as a ‘Christian activist’. He has a degree in theology. ‘For me,’ he says, ‘Christianity does not necessarily mean pacifism. There are certain things that, if you want to destroy them, you don’t have to be violent, but you have to be physical. Christ did that.’

One can imagine that Ramahlele, a vigorous man with close-cropped hair, is as comfortable in the pulpit at the Bloemfontein church where he preaches as he is behind his UFS desk, where he is still a manager today. Ramahlele believes universities should teach universal, not narrow, group values and that university halls of residence should be places where people can learn to live with one another. But he recognises that, even now, this is a point of contention in universities across the world.

Many of the black students at Kiepersol were leading figures in student organisations affiliated with the ANC and other, more radical black groups. Ramahlele’s charges recruited more black students, offering them protection from the assaults and other abuse they faced in the predominantly white reses. Kiepersol was a senior residence, meaning that everyone who lived there had already spent at least a year at the university. For black students, that first year was very likely to be a tough one.

Ramahlele says that Kiepersol had disaffected black students who challenged the system:

I inherited a res which was very angry at the system, very angry at the white people. I inherited students who were once abused within the system. And, as a result, Kiepersol became almost a political institution, for protecting the rights of blacks on campus. And I had to head that. But I’m also a manager in a white system. I had to say, ‘There’s anger, understandably so. But the expression of this anger needs to be channelled in a responsible way.’

‘Blackness was being affirmed and respected under my leadership,’ Ramahlele says, proud that Kiepersol residents were among the first blacks to gain places in student-union leadership positions.

But the future looked uncertain that night of the singing. Ramahlele was at home in the apartment attached to his res, where he lived with his wife. He heard the sound of protest songs dating from the anti-apartheid struggle getting louder outside. ‘I was worried because I had never heard so many students singing at that time of night,’ he says, recalling that it was around 8 o’clock in the evening. He went outside the res to find students armed with bats. He approached them to find out what was going on and they told him they were very angry. Some black students had been assaulted and abused in a residence called D. F. Malherbe. The Kiepersol students were going to rescue them.

Ramahlele tried to dissuade them, telling them the white students outnumbered them and that they were likely to be better armed. Nevertheless, they set out anyway, about 140 of them, some with guns, toward the Volkstaat res. Ramahlele called the director of student housing, and told him he thought a war was going to break out. Then he followed his Kiepersol men.

The white students, meanwhile, had heard trouble was coming. ‘The white students were also being mobilised and organised. They had their bats, and I saw they also had guns,’ Ramahlele remembers.

The white students had called in reinforcements who lived off campus, and they began arriving in their cars. Few black students could afford cars.

The black students toyi-toyied; the white students sang ‘Die Stem’. The national anthem of the apartheid government had, with the dawn of democracy, been combined with a hymn of the anti-apartheid movement, ‘Nkosi Sikelel’iAfrika’, in what was meant to be the uniting theme of a new South Africa. The Xhosa, Zulu and Sotho lyrics of ‘Nkosi Sikelel’iAfrika’ call for divine help in banishing wars and strife. ‘Die Stem’ proudly extolls the beauties of the country.

There was no such harmony on campus that night in 1996. Ramahlele, however, was able to persuade the black students to retreat when they saw the growing force of white students. As the black students ran back to Kiepersol, they smashed the windows of parked cars, which to them symbolised white privilege and arrogance. The white students followed them. Hundreds, if not thousands, surrounded the black students, who had now reached the safety of their res. The white students threw stones, breaking every window in the building. The police arrived, as did higher-ranking campus officials. White officials pleaded with the students outside; Ramahlele kept talking to the students inside, and kept in touch with his colleagues by phone. Around midnight, the white students were persuaded to return to their reses.

Among the senior officials who rushed to the campus to help Ramahlele was Benito Khotseng. In 1993 Khotseng had become one of the university’s first black senior managers. Years later he would offer me further insight into this piece of history and was, like Ramahlele, willing to relive the turmoil of the past. The two also display a remarkable resilience that I see as the real story, a theme that comes up again and again in the stories of South Africans.

Early on, Khotseng’s job had entailed recruiting students. He also took on the role of finding scholarships for black students, and creating special classes to ensure that students who had had the inferior education afforded them during apartheid could keep up academically at a formerly white university. And although not a formal part of his job description, Khotseng’s duties, out of necessity, came to include trying to keep racial confrontations from flaring into violence.

Another confrontation in 1997 nearly spun out of control at Karee, a residence that had suddenly seen its proportion of blacks rise from zero to 30 per cent. White students at Karee surreptitiously added a laxative to the sandwiches served to the students at afternoon tea. The white students made sure black students got the tainted food, saying they resented the newcomers helping themselves to what they saw as unfair portions. The laxative had a powerful effect: several badly dehydrated students had to be hospitalised.

The next day, retaliation came for the laxative stunt. Two firebombs were thrown at guards at the university’s front gates. Dozens of black students descended on a central hall where exams were being administered. The white students fled, leaving their black counterparts toyi-toying outside the hall. More white students began heading to the hall from residences then notorious for their militant racism – Reitz, J. B. M. Hertzog, Verwoerd.

While a white senior member of university management, Vice-Rector Teuns Verschoor, pleaded with the white students to return to their residences, Khotseng did the same with the black ones. Eventually, the two sides were separated. ‘Later on, I asked Teuns, “What do you think happened?”,’ Khotseng recalls, sitting in the dining room of his home on the edge of campus. His face is unlined, but thick-lensed bifocals hint at his years. Verschoor and Khotseng came to the conclusion that, for all the meticulous planning to bring more black students to the university, including installing Ramahlele as a res head, they had not given enough time to prepare black and white students to study and live together.

It’s not that Khotseng and other university officials did not understand there was a challenge to be overcome. Ramahlele would not have been hired as a res head had they not. And Khotseng had been a frequent visitor to black, white and integrated residences. He’d spoken to students about what to expect and what was expected of them. Students regularly came to his office with questions. He had taken to spending weekends on campus, mentoring and advising students. But, in the end, Khotseng came to believe he should have done more, and done it more systematically.

‘In a way, I realised we let change take place very fast, without facilitating it,’ he says. ‘We encouraged black students to come to campus. But the effort that we put in to convince white students to accept black students as their equals was very little. Many of the Afrikaans students who came to the university were from farms,’ he says, explaining that these students’ exposure to black South Africans had been hitherto limited to the farm labourers on their families’ estates. When they got to the university, they had to accept black students as their equals. ‘We did very little to assist them to change. We should have done a lot more homework. We should really have worked on them,’ he says.

Khotseng had fastidiously prepared for his role at UFS. His first experience of the university was in the 1980s. The former high-school teacher had risen to become an administrator in the education department of the government of Qwaqwa, the impoverished homeland that the apartheid government had set up for the Free State’s Sotho-speakers.

In a tactic that amounted to a subtle undermining of a system meant to smother black people’s aspirations, Khotseng sought help from researchers at what was then the University of the Orange Free State. He wanted advice on planning budgets and curricula. His aim, he said, was to improve education for blacks. And white people helped him.

‘In order to see the success of apartheid, I guess, they were bound, in a way, to support us in separate development,’ he says.

Not that his welcome was warm. As he visited the library and offices of the university, he found himself challenged by white students and staff who seemed incapable of addressing him in a normal tone of voice. ‘There used to be a lot of anti-black people,’ he says. ‘I was never really accepted.’

This was just a few years after the rector of the university had severely reprimanded, according to the university’s official history, the captain of the student chess team for taking part in a chess tournament at another university where non-white (in this case, Chinese) players had been welcomed.3

‘I was one of the first black people to come to campus as a researcher and visit the library,’ Khotseng says. ‘People used to shout at me. They would be howling at me: “What do you want? What are you doing here?” And I would say, “I’m here doing research.”’

In the early 1990s, Sotho-speakers began to champion the idea of a ‘university for ourselves’, as Khotseng puts it, drawing out the last word for emphasis. He was among those who advocated a partnership with UFS. He explained how he had learnt to work with Afrikaners while doing research there in the 1980s. Many Sotho-speakers also spoke Afrikaans, and the Qwaqwa administration was already working closely with Orange Free State bureaucrats, many of whom had trained at what would become UFS. ‘I worked with them and understood them and how they worked,’ Khotseng says, referring to Afrikaners.

Khotseng also portrays this proposal to UFS as a tactic in the fight against the system that had established universities based on the race of their students. ‘People wanted to defeat apartheid,’ he says. His colleagues ‘wanted to indicate to the government that there should be but one university. They realised it would not be possible to have more than one university in the Free State.’

But Qwaqwa’s overtures to what it saw as the natural partner for a university for its people were rebuffed. Officials were directed to work instead with the University of the North, an institution established for black people. However, the University of the North was some 700 kilometres from Qwaqwa (in what is now Polokwane) and in a region where blacks were as likely to speak Tsonga or Venda as Sotho. It was poorly funded compared with UFS, as Khotseng knew, as that is where he had completed his master’s. As the UFS history relates in matter-of-fact prose, with the entrenchment of apartheid in the 1950s, ‘the white government provided white, Afrikaans universities with generous financial support’.4

In the early 1990s, a University of the North campus was established in Qwaqwa. Khotseng taught philosophy and education there, and became dean of its education department. In 2003 that Qwaqwa campus became part of UFS.

In the 1990s, ambitions were being realised in South Africa. In December 1989, a prisoner met a president – Nelson Mandela and F. W. de Klerk. On 2 February 1990, De Klerk unbanned Mandela’s ANC, and in Paarl nine days later Mandela walked from prison to be greeted by cheering crowds. In 1993, negotiators representing Mandela and De Klerk, and others completed a draft Constitution that opened the way to all-race elections on 27 April 1994.

Bloemfontein, once the capital of an independent Afrikaner republic, now has a Nelson Mandela Drive, winding from a shabby neighbourhood of mechanics’ garages and used-furniture shops, past the city hall, and on to a new part of the town, which sports a mall and the gleaming regional offices of large South African corporations. The main gate of UFS is on Nelson Mandela Drive.

As the date neared for South Africa’s first free elections, university officials let it be known they wanted a black educator to help put them on the map of a new South Africa.

‘I applied with interest,’ Khotseng says. ‘Here was an opportunity for me to assist the university and assist the Afrikaner to change, and to help us achieve what we wanted – which was to improve education for blacks in the Free State.’

He got the job, but Khotseng wanted to be sure that those who hired him saw him as a member of the team, not an outsider who was simply being tolerated. The language issue was revealing. Sitting at his dining-room table, Khotseng pulls a copy of letter from a file that he sent to the rector in February 1993, in Afrikaans, asking where his new post fell within the university structure. He insisted on a job title and a clear job description that he felt reflected the position he had assumed. The rector responded to the effect that Khotseng was his adviser on special projects – raising funds for scholarships for black students, planning multicultural training to help black and white students and staff learn about one another, and recruiting black students and staff.

That clarified the role, but Khotseng wanted to find out exactly where he fitted into the organisation. ‘I challenged them. So the principal had to go to the council. In the end, they said that they would establish my post as deputy vice-rector for student affairs,’ Khotseng says of the title he was eventually given. It was a breakthrough for a black academic at any formerly white university in South Africa.

He also asked that his daughter Nthabiseng be enrolled at the university, another step he had to take up with university officials. His daughter’s presence made it all the more important that an atmosphere welcoming to black students be created, Khotseng says. More black students would have to be recruited, a task he took on, along with identifying staff members who would be willing to help the new students settle in. And he urged the rector to take steps to train and nurture black academics who could rise in staff positions at the university.

Khotseng came to change a university, but he says he quickly realised he would have to change himself first. He had been a high-school teacher, a university professor and an education bureaucrat in a segregated system. He knew he was no expert in transformation. So Khotseng began to read, exploring studies on the psychology of race and on race in the workplace. He took a six-month management course at Harvard.

He encouraged colleagues to conduct at least some university business in English, but also worked on his Afrikaans. He told them, ‘You guys have helped me to learn Afrikaans. We must take this a step further: you must learn Sotho. I must teach you Sotho.’

His colleagues, he says, were excited at the opportunity. He put together a Sotho phrase book for managers, and the Afrikaners who used it almost immediately saw the benefits in terms of better relations with the black cleaners and other support staff they had once taken for granted.

‘I had first of all to change my attitudes towards other people in order to be able to change them,’ he says. ‘I realised I had to get interested in their way of life, and show them things that could get them interested in my way of life.’

Language, then, did not have to be a point of departure. Black and white South Africans share this: they hold their native tongues dear, and that can be an opening to learning to respect one another’s languages in a nation that today has 11 official tongues. ‘I didn’t have any problem speaking Afrikaans,’ he says. ‘But I insisted they also should speak Sotho.’

Khotseng sought allies, many of them the white women who felt undervalued in tradition-bound, patriarchal Afrikaner society. He championed the promotion of white women to senior positions. Here was a black man able to see the world from the point of view of white women:

When I came here, women – even though they were white – were in a way discriminated against, left out, in terms of management. I started bringing up the issue of women in management. White women saw me as someone who brought them in. That made it quite easy for me to work with white women on campus. They saw that I was very positive as far as they were concerned, that I felt they needed to be treated as equals and that they needed to be given opportunities.

As he speaks, Khotseng places his hands together under his chin, fingertips lightly touching, as if he were holding a delicate piece of pottery. Khotseng says his experience at UFS taught him that change has to be handled as if it were something fragile. He believes that the unrest in the campus in the mid-1990s resulted from a failure to communicate and monitor. The bridges he had built to women in the university helped his mission because he was able to speak to the women who headed the female residences. He learnt that they had worked to welcome the black students – something the heads of the male residences had not done. The female residences had not experienced the kind of turmoil that the male residences had, he says.

Then, Khotseng explains, university officials, shocked and uncertain, made another mistake: they did not continue to demand that students integrate their reses.

‘We should have pushed for it during that period,’ he says. ‘We should have worked hard to try to encourage it more and more. And we didn’t.’

Khotseng shows an adeptness for adaptation I have come to see as quintessentially South African. His own story, with the rebuffs he first experienced in Bloemfontein and the violence he was unable to prevent later, could have been a blueprint for bitterness. But I hear strength in the calm with which he tells his story to me. His is a journey that tempers and teaches.