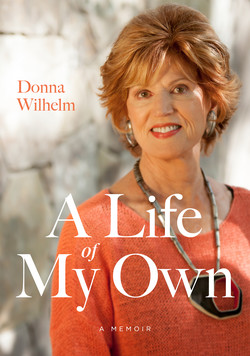

Читать книгу A Life of My Own - Donna Wilhelm - Страница 11

ОглавлениеFleeing the Old World

Mother’s Lost World

Most days, I didn’t know which Mother would show up—unflinching dictator or consummate actress. Would she punish my rare acts of rebellion with a leather belt? Or would she draw me close to her with stories of long lost times in Old World Poland? Would she dictate how I behaved, how I dressed and what I ate? Or would she transform into the pampered young woman of her youth, living in affluence?

I would take my place on a wooden chair in Mother’s kitchen strewn about with unwashed dishes and leftover food—to watch a drama I named “Mother’s Tragic Destiny.” I’d put on imaginary sepia toned glasses that made the past come to life. Mother the actress, whose voice rose and fell with compelling emotion, pulled me into the web of her stories.

Hania Olsezska was the sole daughter among eight children born into a family of notable Polish landowners. Although she never admitted her exact birthdate, I estimated my mother was born around 1900. The Olsezski family (in correct Polish, a woman’s surname ends with an “a” and a man’s or the plural version with an “i” or “y”) lived just outside Warsaw in a white stone villa surrounded by acres of manicured gardens and a dense, fragrant forest that buffered and disguised its isolation. Unlike boys of Mother’s aristocratic class, girls rarely attended public school or university. They were educated at home by tutors. “In Poland,” Mother explained with a sad smile, “girls like me learn Catholic religion, painting and embroidery—I was best for watercolor flowers.”

Mother never imagined she would have to rear children without a nanny or lift a finger to clean house. And she couldn’t have predicted that her elite world of luxury was doomed.

In 1918, the Bolsheviks murdered the Russian Tsar Alexander Nicholas II and his entire family—the last of a long line of autocrats that had ruled Russia since the 1500s. Violent purges followed. Like an avalanche of death, the Bolsheviks eradicated Tsarist sympathizers and rampaged into bordering countries including Poland. All wealthy landowners were suspected of having links with the Tsar. Unless those links could be manipulated, aristocratic families faced terrible consequences.

To save their seven sons from the Bolsheviks, the Olsezski parents were willing to sacrifice their only daughter, Hania—my mother. They concocted a preposterous plan: to convince Polish society and the Bolshevik spies that all but one member of the Olsezski family opposed the Tsar for his “sins against the people.” Her parents fabricated a friendship between the innocent Hania and the Grand Duchess Maria, one of the Tsar’s daughters. Hania would be publicly shamed and condemned for betraying her family, the honorable Olsezskis, staunch and loyal supporters of peasants and the common folk of Poland.

“Ach, Danusia, I am rebellious girl always.” Mother raised her flaccid arm to the sky. “Eighteen years old, I’m daughter in disgrace.”

Hania’s parents bribed an artisan papermaker in Warsaw to produce a few sheets of rich vellum paper encrusted with a counterfeit copy of the Royal Seal. Then they convinced Hania’s governess to forge a flowery letter in the style of eighteen-year-old Grand Duchess Maria, supposedly written to her secret friend, Hania Olsezska. The final bribe to Warsaw journalists stimulated reported stories affirming the Olsezskis’ vehement opposition to Tsarist principles. The fabricated letter that exposed Hania’s friendship with Grand Duchess Maria was passed around Warsaw’s opulent salons. And gossip flared.

Mother’s talent for storytelling was seductive. She lured me into the fictitious friendship between herself and the Grand Duchess Maria. She enticed my imagination with vivid scenes of intrigue and danger facing two reckless young women in a village near Tsarkoye Selo, the Tsar’s summer palace. Mother’s eyes sparkled with excitement as she described how the Grand Duchess “disguised as servant girl” in the palace kitchens persuaded a peasant farmer delivering fresh vegetables to transport her from the palace to the village. There, her adoring friend Hania waited in an aunt’s nearby cottage. A secluded, vine-covered dwelling—“My auntie Mariska, old and deaf, not know what we were talking”—became the friends’ perfect hideout.

Mother strutted about, head held high. “I’m remember every word of Grand Duchess Maria in letter,” she boasted. “‘How I loved pretending we were free,’” she recited. “‘Everyone else in the Olsezski family detest Romanovs for royal power over the people. You alone, dear Hania, are my secret friend who does not fear adventure.’”

Beguiled by Mother’s fervor, I absorbed the passion of two young women pursuing a forbidden friendship in a world where spies were everywhere. My body tensed when Mother paced around, hand pressed over her heart. As she glided toward the high-back kitchen chair and settled into the seat, I ascribed alluring grace to her and dismissed her thickened body. Her calloused fingers became beautiful and manicured. I even added a tasteful gold ring with a single pearl to her slim finger, my idea of a perfect gift from her parents. My longing for beauty and a respite from the drudgery of boarding house life allowed me to spontaneously transform Mother into the proud and privileged girl of her youth.

Neither Mother nor I would forget the romantic ending to the infamous letter.

“‘Write to me as you always have,’” Mother quoted from memory. “‘Address your letters to my lady in waiting, Baroness Sophie Buxhoevden, who will guard our secret. Forever your friend, Maria Nikolaevna Romanova.’”

In that long-ago patrician world of Warsaw, young Hania suddenly disappeared. Outsiders assumed that she was cloistered in shame, hidden behind the walls of the Olsezski estate; however, her parents had rushed their only daughter to a covert destination—Gdansk, the Polish seaport city. There they put young Hania aboard an ocean liner bound for America. Not speaking a word of English, she would travel alone.

In Gdansk, Hania cried bitter tears and embraced her parents for the last time. “They tell me, ‘You are only hope for us—have courage to save the family!’”

On the departure deck, Hania listened as her parents gave their final orders: on her first night at sea, Hania was to make her way, unobserved, to the aft deck and fling all her identity papers overboard. On her own, she would have to convince American Immigration that she was a political refugee seeking asylum. She’d have not a shred of evidence to link her with the Olsezskis. Her family’s very survival depended on her ability to disappear, validating the rumors of her betrayal.

While Hania journeyed toward an unknown future, her parents returned to Warsaw to stage press interviews. Publicly, the Olsezski patriarchs appeared outraged and vehement. Their rebellious daughter had not only betrayed her family, she had fled Poland without their knowledge. “Stories about me in all newspapers,” Mother said with a defiant nod as if daring me to contradict her. “I must leave my homeland behind,” she said, pausing to cross her hands over her heart—“forever!”

Arriving at the docks of Ellis Island, New York, a teenage Hania summoned up formidable courage. “I’m looking straight into eyes of Immigration mens,” she said. “They believe my story of persecution in Poland and welcome me to America! But with new name. No more Hania Olsezska—I’m become Harriet Olse.”

When she came to the end of her story, Mother sighed. Her ample bosom rose and fell with subsiding passion. Her eyes fluttered closed. Her cheeks, sagging and badly powdered, were streaked with tears. All traces of her patrician youth and vigor drained away, leaving only an exhausted old woman. She slumped in an ordinary chair and breathed the odors of leftover food in her boarding house kitchen.

Hania in America, 1920s

Was my mother’s story incredible? Of course it was. Yet I consumed it like manna for a starving soul. At night, I dreamt of Hania sobbing into bitter cold winds and flinging her identity papers overboard into the vast Atlantic Ocean. And I succumbed to a fantasy that Mother was not entirely betrayed by her parents, that she had left the Old World with tight bundles of jewels sewn into secret pockets of her clothes. How else could Hania and Juzo have purchased “them bigger and bigger houses” in America?

I yearned to give teenage Hania, arriving alone in America, a special gift—English fluency, a secret skill to make her life easier.

Decades later, advanced technology helped me fact check Mother’s tales of long ago against historical events. What I learned added layers of incongruities to Mother’s accounts of being banished to America. Research confirmed that Hania Olsezska, born in 1892, had arrived in America in 1911 (one year before the ill-fated crossing of the Titanic), when she was age nineteen. Glaring fact affirmed that Tsar Alexander Nicholas II and his family were not executed until 1918—years after Mother actually landed on American soil. Had Mother reinvented her past?

There had been a lot of unrest in Russia before the murders of the Romanovs. Perhaps, given the impending threats to Russia’s rigid class system, Mother’s parents had anticipated the dire repercussions and dangers to neighboring Polish aristocracy. If so, they might well have deemed young Hania as the most dispensable member of their family and sent her off to America in a preemptive defensive move. I had concocted my own mystique about teenage Hania, with her feisty character and sheltered ignorance of political realities—and my fertile imagination had elaborated on the possibilities. For a calculating family, she would have been a vulnerable candidate, easily persuaded to embellish stories about her friendship with the Romanov princess.

Hania was a passionate young woman imbued with a vital mission and destiny that only she could fulfill by fleeing Poland. I had to rationally weigh the historical information I found against Mother’s melodramatic re-enactment that had captivated me during childhood.

However, what I never doubted about young Hania was her formidable courage against adversity. Mother’s stories had become real to both of us. With every retelling, we viscerally suffered and mourned the decimation of the entire Olsezski clan. Mother described them rendered like slaughtered animals on political killing fields. Her insistence, that not a single member of her family had survived the Bolsheviks, was supported by evidence. I would never encounter a single member of Mother’s family—there were no visits, no letters, no communication of any kind from Poland. According to Mother, the Olsezski estate and gardens, every vestige of abundant wealth was stripped, destroyed or redistributed by the Bolsheviks. The legacy of Olsezski wealth was imbedded in mystery. How else was Mother able to purchase a sequence of large properties in America that provoked the endless gossip among Dad’s relatives? Had a fortune of hidden jewels indeed been sent along with young Hania? No matter that my factual research unearthed questions that could never be answered, what I knew for sure was that my mother had been a courageous survivor. Of what, exactly, would remain an unsolved mystery.

•

In America

I had no one to help me understand how young aristocrat Hania from Poland had become the tyrannical boarding house owner in Hartford, Connecticut. Mother refused to join other “foreigners” taking English classes, instead she taught herself a patois of Polish-English. Mother was infamous for bursting out in unexpurgated Polish during fits of anger with boarders. Not surprisingly, I liked to eavesdrop. And I understood Polish very well—a secret I kept until I was nearly six years old.

One day when Dad’s relatives were visiting us, sitting and sipping cups of hot tea in the family parlor, Mother suddenly left the room. What had alerted her? Driven by curiosity, I followed.

Lurking outside the kitchen, I spied Mother lambasting a pitiful boarder. Mother shouted, “Pies krew!”

I snickered loudly because I knew “dog’s blood” was a really bad curse word in Polish. Mother didn’t miss anything—when I laughed at her swear word, she knew I understood Polish. Her punishment was swift. Mother marched me back to the parlor and pushed me to the center of the room to face all the relatives.

“Stand straight!” she ordered. “Danusia so smart, she show how good she know Polish.” She turned to me. “So, you tell something you know very good in Polish. Loud so they hear!”

No way could I repeat the curse word. I thought of only one thing that might not get me in even more trouble—a tongue twister that I’d memorized from listening to a Polish boarder repeating it again and again. It was a real good one, so difficult to say quickly that even native Polish speakers had trouble: “Stól z mieszanymi nogami”—a table with mixed-up legs. The relatives were impressed and tried to repeat the tongue twister. But not a one of them was as good as me. Mother’s eyes began to sparkle as she listened to me besting the relatives. I could tell she wasn’t angry anymore. Revealing my secret would make it harder to eavesdrop, but it was one of the few times in my young life that Mother showed her approval of me.

Mother was too stubborn to learn how to read and write English. I was stubborn, too. I refused to learn how to read and write Polish, and no matter how fluent I sounded, I remained Polish illiterate. In truth, neither Mother nor I had much tolerance for other people telling us what to do.

I wondered if we had something else in common. As a child, I often felt lonely. Had Mother, too, felt lonely with no one to help her adjust to a new life in America? She’d been pampered and sheltered in her youth—what could have prepared her for future adversity and isolation? I had questions, but getting the truth from Mother was no easy business.

On one of her quiet days, however, I plunged in and asked her, “Mamusia, how did you get from Ellis Island to Hartford?”

She turned her back to me and walked to the stove. No answer.

I tried again. “Did you have a job?”

Mother perked up and turned around with a smile. “I get work in photography studio,” she said, her voice filled with pride. “They hire me to paint black and white photographs and make them look like expensive color portraits.”

Later on, I’d reflect on Mother’s privileged background. How ironic that as a young pampered girl learning something seemingly impractical—like painting flowers in Old World Poland—helped her as an orphaned refugee find work in America.

I pressed on to learn more. “How did you meet Tatush?”

Her eyes softened. “Ach, he is coming to photography studio for making official family picture.” She flashed a coquette’s smile. “When boss ask if anyone speak Polish, they come to back room where I am painting and send me up front, for make sure customer order most expensive color portrait.” Apparently Juzo impressed young Hania with his job as assembly line mechanic at Pratt & Whitney Aircraft Company in East Hartford. “Was good money then, many Polish immigrants want jobs—not many get them.”

“Did you fall in love?”

“Few months later, we marry.” No details.

I couldn’t imagine my parents as a young and tender couple. As a wife, Mother was tyrannical and showed my dad little affection. As a young mother to my sister Edith and the mysterious Holden Girls, she was harsh and drove them away. Edith was the only one who came back for more, although rarely. Mother’s relentless “gifts” of leftover dinners and over-ripe apples were confusing in light of her otherwise miserly affection. Later there would be other gifts to strangers, many of them life-changing.

Dad and Mother as newlyweds, ca. 1919

Edith, Mother, and Dad, ca. 1923

Schooldays Inspection

My upstairs closet was a lonely wasteland. One metal rod separated two sections into ugly and pretty. The ugly side held wire hangers and my horrid school clothes. The pretty side had nice wooden hangers. On one, hung my soft chenille bathrobe that kept me cozy every morning and night. On another, my pink satin dress, size Junior-Large, trimmed with a meager row of lace along the neckline. Even when I had no real place to go, I’d put on that dress, stand in front of my bedroom mirror, and imagine I was a beautiful princess.

Three pairs of shoes didn’t take up much room on the closet floor. One pair of scuffed school loafers squatted next to muddy olive rain boots. Behind them sat a tightly closed, chocolate brown shoebox from G. Fox & Company. When I lifted the lid and spread open the tissue paper, a glossy pair of black patent Mary Jane’s made me giddy with pleasure. Every week I rubbed a gob of Vaseline over the leather until my fingers were reflected in the glistening surface. If it hadn’t been for the wedding of one of Dad’s relatives, I never would have gotten the dress or the shoes. Mother only bought them because she didn’t want to be embarrassed by her daughter dressed in shabby school clothes and dirty loafers at a fancy wedding. The bad thing was that my feet and my body were growing too fast, and soon the beautiful Mary Jane shoes and my princess dress would be too small.

Every school day, my mother stood like a warden at the bottom of the stairs, ready to inspect me. I’d descend, halt in front of her before rotating around like a robot. I don’t remember ever being sent back upstairs to change—there was nothing in my closet she hadn’t chosen. What I never forgot was the disgusting odors of Mother’s soiled housedress.

Post inspection, she ordered me to the kitchen and planted her overflowing bottom on a high-back chair. I squirmed on a small wooden stool in front of her. “No move nothing!” Her hand waved a pig bristle brush. Unlike the bobbed style copied by all the “in girls” at school, my auburn hair had never been cut. When loose, it fell below my waist.

My sweaty, pudgy fingers gripped the edge of the stool. If we had fifteen minutes, Mother might do “donuts”—two coils of braids tightly wound into circles above my ears, anchored by hairpins stabbing into my scalp. If time was tight, she either twisted my thick hair into one fat braid tapering into a rubber-banded stump, its wayward ends fanning out. Or she yanked my hair into two ruler-straight braids measuring from my ears to below my shoulders.

In school, I tried to act as if being different and looking different didn’t matter to me. But that was a cover up, because my classmates’ stares and taunts shaped a daily gauntlet I had to pass though.

“Mamusia, I hate my old-fashioned clothes and hair—they make me look like an immigrant!”

Mother’s face turned red like a boiling beet. Her pale blue eyes darkened, and she began to scream in Polish (I’m embarrassed to translate). Furious, Mother stomped out of the kitchen. I didn’t move from the stool, even though I knew what was coming. Behind her bedroom door, The Warden grabbed the hanging leather belt, wrapped the buckle end around her hand, and marched back to teach me a lesson that I hadn’t learned the last time.

Her hands never touched me. Instead, she lashed the belt wildly at my bottom and my back where bruises wouldn’t show. Her outbursts were predictable. It was impossible to know what would bring them on. And that was what frightened me the most about my mother.

The big kitchen clock got The Warden’s attention. “Now time go to school!”

Passing the hall mirror next to the front door, I couldn’t stand looking at myself. I fumbled with the heavy lock, sighed deeply, and began the thirty-minute walk to school. My bottom still smarting from the morning’s punishment, I consoled myself with the memory of gentle Brutus and wished he were still alive and by my side.

Mother’s influence over me would last a lifetime. As a wife and a mother, I would ask myself again and again: How had I allowed Mother to insidiously shape my expectations, weaken my self-confidence, and expose my vulnerabilities? Why couldn’t I see her as a fractured role model and trust that I deserved unconditional love? Her character, formed by adversity, would weave itself deep into my psyche. Years later, I would finally be able to reconcile that despite the angst, fear, and rebellion that she had provoked in me, she’d also inspired my fortitude, courage, and resilience.

Dad and the Farm

Juzo, aka “Joseph,” Sosinski, resembled a bald-headed Ike Eisenhower in khaki casuals, as he drove the 1950s Packard sedan with silent intensity. Beside him in the passenger seat, I stretched up my eight-year-old body and craned my head left and right, like a vigilant bird that couldn’t risk missing a critical opportunity. Dad said our journey was to check on things at the farm. But we both knew the real purpose was to escape from Mother who, for mysterious reasons, avoided going to the farm.

Carefree times were rare, and I savored them. For me, the farm was a place of refuge and wonderment. For Dad, the farm offered freedom—to eat simple meals, to enjoy nature, and to withdraw into silence. I felt my presence at the farm was almost irrelevant to him.

Old Glendale Farm was located in the township of Hebron, some eighteen miles from downtown Hartford. During my childhood, the farm was prime rural property—300 acres of fertile pastures, rambling hills, meandering streams, and secret caves. Driving there took us through Connecticut tobacco country, where miles of low-rising, voluminous canopies flapped ever so slightly in the breeze, not tall enough to be tents, yet appearing endless and ominous to a little girl with a big imagination. “Tatush, what goes on under those long white sheets?” I asked.

He tightened his grip on the polished wood of the steering wheel. “Don’t ask foolish questions.” Dad didn’t want his reverie disturbed. I retreated to my fantasies: Under the white-covered fields, hordes of men with dark skin labored—bent and sweating. They sorted whatever grew in those fields into massive bundles.

Decades later, still curious about those mysterious canopies, I did some research. During the 1940s and early 1950s our route to Old Glendale Farm took us through “shade tobacco” country. The white canopies of my childhood fantasies were actually meant to increase the humidity around the crop of tobacco designated for manufacture of high-end cigars.

In the 1950s, smokers received no dire health warnings. Advertising genius of that era instead created a mystique about smoking. Adults puffed away guilt free. Gutsy kids hid in the bushes, coughing and smoking like they were grownups. Glamorous Hollywood stars like Ava Gardner, Rita Hayworth, Frank Sinatra, and James Dean smoked to look sexy, savvy, and virile. Magazines and billboards promoted The Marlboro Man as rugged and handsome. Smoke swirling around his Stetson, he gazed out over America’s big, bold country, and passersby were hooked. For almost a century, this coveted harvest was Connecticut’s number one agricultural export.

Dad slowed the mighty Packard as we approached the rural village of Hebron and passed a cluster of stone houses, momentary interruptions to the surrounding farmland. In those years Hebron had no enticing farm stalls with fresh produce for sale, no country store serving hand-churned ice cream—what it did have was lots and lots of stone. Centuries before, Yankee ancestors had tilled up more stones than soil and used them to build boundary fences so solid they would last hundreds of years.

Soon the road narrowed into a single country lane, where distance between the roadside mailboxes suggested the size of a property. Anyone wandering by would think Old Glendale Farm was modest, if they judged it by the ordinary stone farmhouse. The two-story structure was built on a slight rise set back about fifty feet from the road. The Packard bumped onto the rocky driveway alongside the house. The farmhouse’s façade seemed to have been crafted by quilters working in fieldstones. A quirky wood balcony, too small for a human occupant, jutted over the front door. I never could come up with a practical purpose for it. Across the front yard, wildflowers danced on uncut grass, no sign of a human gardener working a lawn mower. The ramshackle toolshed behind the house had no visitors. On the opposite side of the road, the derelict gray barn loomed. Who else, besides me, could hear the ghostly mooing and jostling of past dairy cows waiting for farm hands to milk them?

Unable to contain my excitement, I leaped out of my seat as soon as the motor stopped and scrambled up the stone steps to the concrete veranda that wrapped around the house. From all sides, the views were glorious. I breathed in the fragrance of the land—a heady mix of field pollen, rotting apples fallen from the trees, and seedlings sprouting in the vegetable garden. Dad planted seeds on impulse. Given the randomness of our visits to the farm, we never knew what had survived for us to eat. Eyes squeezed shut, I plopped down on the cement and began my counting game: “One, two, three, four, how many things do I remember—”

“Danusia,” Dad called. “Come help.” He stood by the Packard with all its doors wide open. Mother wouldn’t let us leave the house in Hartford until she’d stuffed the back seat of the car full of chipped bowls filled with food we’d never eat: oozing leftover ham, mounds of over-mashed potatoes, and dollops of cooked cabbage layered with solidified grease. Loaves of sliced pumpernickel and rye bread got harder by the minute in their paper envelopes wedged between the ubiquitous squat jars of Polish dills and pickled red beets. On the car floor sat stacks of Popular Mechanics magazine and a week’s backlog of The Hartford Courant and Novy Swiat that fed Dad’s insatiable need to know what was happening in the world. Upright next to the periodicals, a large brown paper bag held my stuff: my pull-on rubber boots, pink chenille bathrobe, flannel pajamas, and finally, my treasured collection of paper dolls in the fliptop cigar box. Folded on top was my yellow raincoat for storms that came without warning and the scratchy wool sweater that I hated but wore anyway when it turned cold.

We loaded up and made our way to the back door, only to drop everything on the cement while Dad fumbled with the rusted lock that never got oiled. Door unlatched, we reloaded and staggered into the farmhouse kitchen, looking for empty space on the long wood table. No luck—it was overrun with crockery from our last trip to the farm, of Mother’s cooking long discarded. I don’t think disorganized Mother kept track of her diminished supply of dishes in Hartford. Maybe she just kept buying more Polish blue and white pottery as a way to remember her heritage.

We piled all our stuff wherever we found room—Dad and I had no sense of keeping things neat or clean. At the farm, we usually gobbled what we couldn’t have in Hartford: fresh eggs from our neighbor’s coop; canned Campbell’s soup disparaged by Mother; and varieties of pears and apples untouched by insecticides. Oblivious to disorder and disrepair at the farm, Dad and I heeded only Mother Nature and the Emerson radio’s weather reports.

The entire second floor was mine to explore. I raced up a flight of creaky stairs, combing my way through the cobwebbed hallway connecting too many bedrooms to remember. Except for mine—the best and the oddest shape, as if it had been sliced away from the bigger room next door. Inside was everything I needed: an iron bed frame hugging a single mattress; one rickety chest of drawers; a drop-leaf table inscribed with old graffiti; and a petite chair, the seat unraveling into raffia puddles on the floor. No closet—wooden pegs along the wall were more than enough for my meager wardrobe. The casement windows begged, “Fling us open!” And I did.

My childhood fantasies reinvented Mother Nature as my beautiful companion at the farm. With every change of season, I cast Mother Nature as a beneficent queen with transformational powers. In spring, she coaxed the abundant trees to bud in yellow and pink so that they appeared to me as billowing ball gowns. In summer, she covered ponds with green algae and cast a dancing net of flying insects over them. When fall came, she dipped her paintbrush into earthy shades of umber, flashes of coral and hues of brown. In winter she became the arrogant Ice Queen, freezing every surface into sparkling diamonds, gleaming platinum and shimmering gold. My little room at Old Glendale Farm became a fantasy setting that Goldilocks herself would’ve loved.

Dad slept downstairs. His bedroom at the farm was a converted storage closet near the kitchen—its’ walls made of thin wood siding were an inadequate shield against the harsh outdoor temperatures, meaning inside was cold and drafty all year. But Dad was used to sleeping cold, and alone. At home in Hartford, he spent his nights in the enclosed and unheated sleeping porch that was beneath the boarders’ second-floor kitchen. As a child, I never saw him enter Mother’s bedroom. And as an adult, I reflected back on the emotional barriers and striking contrasts between my parents. Mother was a woman who unleashed drama and temperamental outbursts that kept the many boarders and me on guard and in line. Dad, on the other hand, was a man of silence and emotional detachment, seemingly oblivious to boarding house turmoil and Mother’s volatility.

Tranquil days at the farm could have brought my dad and me closer together. Yet even there, we remained separate and undisturbed. Nearly every morning, I’d scrounge up odd bits of bread and apples for breakfast and listen to the weather report. If the forecast was good, I’d shove a small flashlight into my burlap sack and take off on yet another solo expedition to rediscover hidden caves I called “my secret places.” For hours, managing to beam the flashlight, I’d forage in their damp and dark interiors for ancient arrowheads and exposed bits of what must have been Indian pottery. On my way home, I’d sing out my childish glee, accompanied by the rattling burlap bag of oddities.

On days when the weather was iffy, I’d stay closer to home, most likely sitting on the edge of the cement veranda and dangling my short legs over the scratchy cement foundation. I’d watch Dad in the distance driving high upon the antiquated tractor. Never did he hoist bags of seeds or hitch a plow to the tractor. As I tracked his upright image across the fields, I too understood the liberated joy of being far away from Mother commanding, “Do this! Do that!”

Dad seldom revealed clues to his inner life or personal turmoil. I’d assumed that his quiet withdrawn personality was a reaction to Mother’s persistent drama. But one day, when the rains were so heavy that even my yellow slicker and mud boots couldn’t tempt me to go outside, Dad opened up and told me an extraordinary story.

Tired of playing in my bedroom with my paper dolls, I clomped downstairs to the front room. Dad was settled in his favorite chair, the shabby high-back, a reading lamp over his shoulder directing the light to his issue of Popular Mechanics. I gravitated to a low stool next to him. Somehow, that day, I managed to ask the right question at the right time.

“Tatush, will you tell me why you left Poland to come to America?”

Dad lifted his eyes and closed the magazine to set it aside. His glance was affectionate, as if he was pleased by my interest. “So, Danusia, you don’t know my story.” Removing his wire-rimmed reading glasses, he leaned back into the chair. “Perhaps is time I tell you. When I was young man, Tsar’s police make extreme danger for my family.” His voice was low and steady as he spoke.

“We were hard-working farmers.” He nodded as if for emphasis. “Polish farmers, whose lands on northern border by Lithuania were ruled by Tsar Alexander Nicholas II, the Russian who named himself King of Poland and claimed our lands as Russian territories.” Dad’s expression turned grim. “Speaking Polish language, reading Polish books was absolute forbidden. Tsar’s police roam the land like vultures looking for Polish prey.” Dad leaned forward and bent his bald head toward me.

“One day they arrive to our farm,” he said. “I was working in fields. They tear everything, search everything. And they find our Polish books—banned books. Tsar’s police threaten to take my father to prison.” Reaching into his pocket he withdrew his handkerchief and blew his nose several times. “Your aunt Mamie was little girl then, like you. She come running to the field, to warn about the Tsar’s police. I drop everything and rush to house. Must save my father!”

I could hardly imagine my aunt Mamie, now grown heavy and tired from serving customers at Kazanowski’s Deli, as once being a small girl and Dad’s little sister of long ago and far away. I tried hard to imagine my old and silent dad as a vigorous young man working the fields, instead of driving around in a rusty tractor at Old Glendale Farm.

“What did you do, Tatush?” I asked, even though I was afraid to know the answer.

“I tell Tsar’s police, ‘Books are mine, not my father’s. He is man who never learn to read. Take me, not him.’ Police agree. I say good-bye. Whole family crying. They see me leave surrounded by guards.”

I was shocked to learn that my aged dad had once been a courageous young man who saved his own father from an unjust fate. Yet he was the same man who never protected me from Mother’s wild and unpredictable lashings.

Suddenly, Dad stood and walked toward the living room window. He gazed out at the front lawn and barn beyond and no longer seemed to be present in the room, where I sat on a little stool by his empty chair.

“In those days I was strong,” he said, looking out at the rain, “very good runner. When we reach fields, I begin to run. For miles. Tsar’s police chase behind. I lead them into forest where I know all secret places. And then—I disappear.”

I watched my dad’s back as he took a deep breath and slowly let it out. He’d never shown me his emotions before. My brain felt as if it would explode. I wanted to know so much more.

“Did you run all the way to America?”

Dad turned and smiled, then began to laugh. I started to giggle. We were laughing together—it felt wonderful. I didn’t want that to stop. Maybe now Dad and I will stay close, like this.

“Silly girl, America is across very big ocean. First, I go to Germany, work there few years, make enough money to bring whole family by ship to America—parents, two brothers and two sisters, all leave Poland. Never again we fear Tsar’s police.”

“Where did you meet Mamusia?”

“Ach, your mother, she was beautiful Polish girl, strong and brave,” Dad said. His blue eyes began to sparkle. “Has she already told you how she escaped the Bolsheviks, come to America, alone—no family, no nothing?”

I nodded. Rising from my little stool, I moved toward my dad, hoping he would draw me into his arms and hug me close. Instead, he reached into his pocket for his handkerchief. With deliberate care, he rubbed the lenses of his glasses. I waited, arms limp at my sides. Dad slid the glasses into his trouser pocket, turned away from me, and walked out of the room.

Dad’s Polish Family in America, early 1900s